The Russian Revolution was also a sexual revolution. V.F. Calverton was in the avant-garde of materialist explorations of sexuality with his ‘Modern Quarterly’ the freest space on the left for the subject. Here, an important early essay on the new thinking, new laws, and new mores of the Soviet Union.

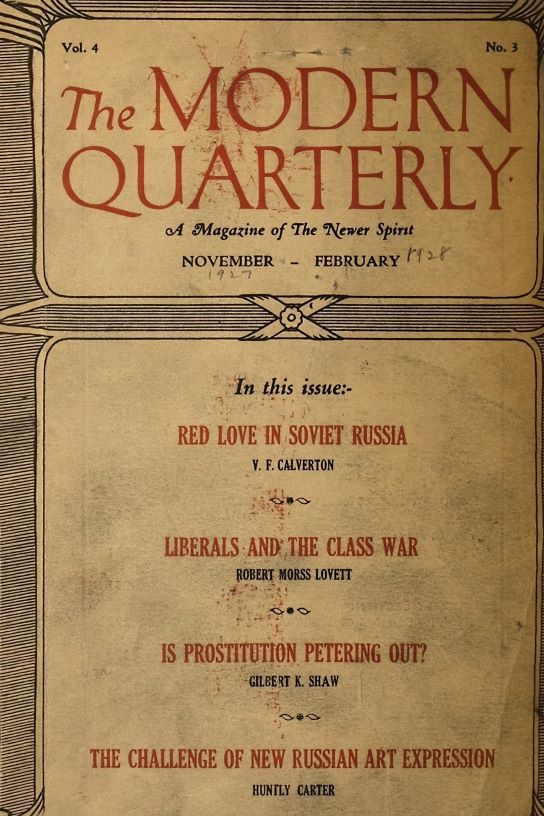

‘Red Love in Soviet Russia’ by V. F. Calverton from Modern Quarterly. Vol. No. 4. No. 3. November, 1927-February, 1928.

GENTLEMEN:

“The success of socialism inevitably will bring about the destruction of the present-day family and the substitution of the ‘free union’ of the sexes, sung of by Bebel, Engels, and the other anointed ones of socialism in those blessed days when socialism was but a theory instead of, as in bankrupt Russia, a sad fact.

(I say “gentlemen”)—

“To achieve this ‘feeling of comradeship, equality, and solidarity,’ prostitution (hire) must give way to the community (free gift) of women to those who zealously follow in the footsteps of a Lenin or a Trotsky. The red comrade is expected to have the proper communistic feeling toward his helpless comrade of the other sex delivered to his lust, as were tens of thousands in the sections where the Bolshevik blight has fallen.”1

So speaketh the earnest Samuel Saloman in his book upon the Red War on the Family, a volume which he humbly dedicates to his “mother and all good women everywhere.”

This is not so strange as it seems, hasty reader–nor so terrible, either. It was not so many years ago when the Tzar of American noose-papers informed his public of the “nationalization of women” which had taken place in Red Russia. And the American public has not forgotten it yet. But how could they, when the American press continues to nurse them with such pabulum? On June 12, 1927, Karl Wiegand, discussing Marriage a la Russia in The New York American, declared:

“The capitalistic view of marriage and sex relations is condemned as ‘small bourgeois view.’ That must not be taken so tragically, however, for in Russia there always was a tendency to follow nature much more than social laws in this respect…

“A provincial control commission of the Communist party, in examining a member as to his conduct and life, something that often is done, asked him about his morals and sex relations. He replied that he was happily married, had a beautiful wife, loved her, and was faithful to her. The commission expelled him from the party on the ground of ‘holding to small bourgeois principles.’

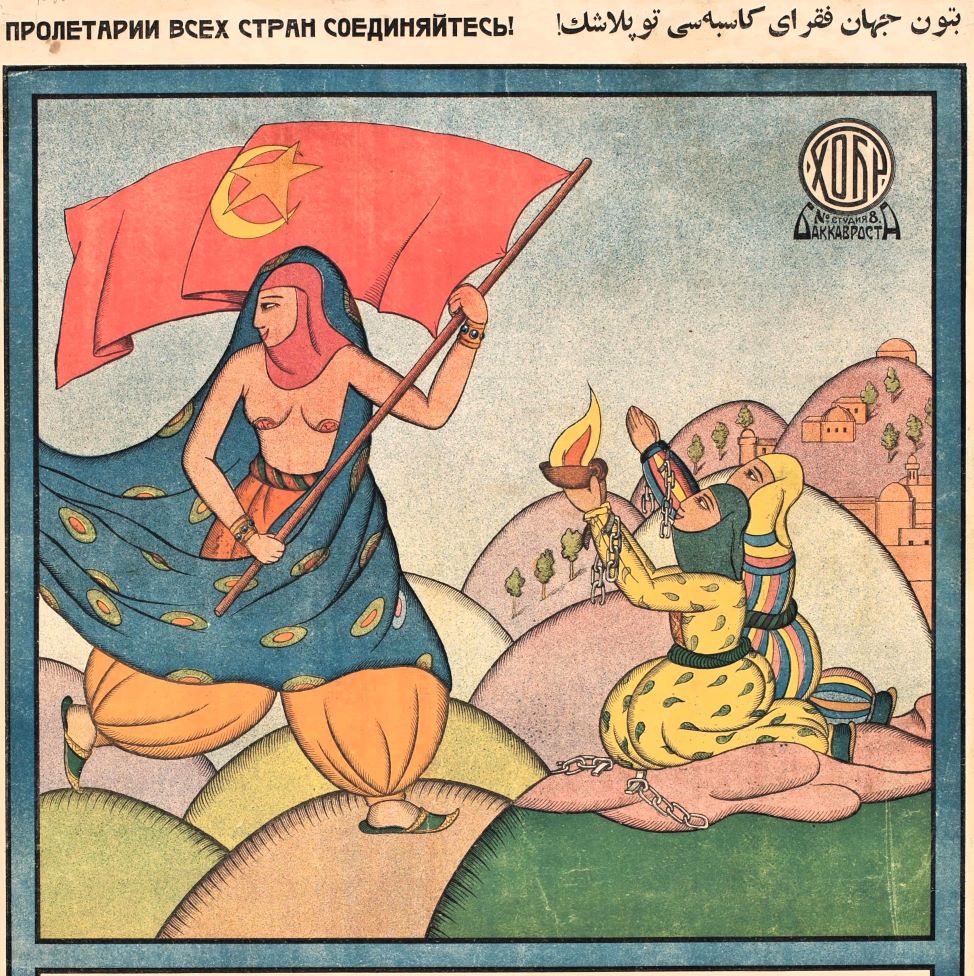

The manufacture of such canards has become a profession among contemporary journalists. The American public is ensnared. And it is not only the American bourgeoisie that is terrified at this wreckage of old institutions! The American worker also is appalled, overwhelmed, tossed between gasps of astonishment at the audacity of these Bolsheviki and gasps of horror at the prospect of their domination over the world. Thus the word “communism” becomes anathema, synonymous with sin. To defeat anyone in shop or organization is but to call him a “communist.” Communism is catastrophe! Communism is red, and red is the symbol of disaster–even though it has always been the banner-color of the proletariat and was the flying ribbon of the American revolutionists. In this the American worker is made safe for capitalism and the company-union!

Of course, this is but one phase of the united front against the U.S.S.R. Across the dollarized world, this literature is rampant. Lenin or Ghandi becomes the thesis of the German Miller. Dictatorship or Democracy becomes the wail of the Italian Nitti. Soviet versus Civilization becomes the battle-cry proposed by the French Augur.2 But these men at least represent, in their attacks, a conflict of philosophies, with an attempt to defend what to them have been the precious aspects of bourgeois civilization. The newspaper diatribes represent nothing more than the dirty, nefarious falsifications of editorial gangsters and journalistic thugs.

Yet there are other phases of the situation that are scarcely less pathetic. Our radicals go to the U.S.S.R, and return with reports that oscillate to the opposite extreme. For them everything has become sanctified. I recall one episode that is typical. En route to Leningrad, the train passed through Latvia on its way into Russia. As the train passed the Latvian border, after the inquiring and intrusive examinations of the Latvian officials, one radical, whom I had met, suddenly was overcome with a wave of enthusiasm, and wanted to get down upon the earth and kiss the “holy” soil of Russia. A beautiful soul, this radical lad, but with a mind like that of Shelley, which could float gracefully among interlacing intricacies of cloud and sky, but would stumble immediately across a tiny tuft of earth. In Moscow, this radical told of his impulse to a Communist.

“Better look over the ground first, my lad, and see who left his traces last, before you kiss it,” was the quick response. In its simple way, this is the difference between romanticism and realism. The Russian communists are the most realistic people in the world. They do not want sentimentality; they do not fear or dislike factual criticism. And when foreigners go back to Germany or England or America and sentimentalize about what they saw, their words become, in the eyes of the Russians, the object of ridicule and not commendation. When a lecturer returns to America and tells audiences that there is less immorality in Moscow than in a Sunday school room, and that prostitution has ceased, the Russian comrades laugh, and those of us who have an affection for reality wonder whether it was romance or rationalization that was victorious.

It is not surprising, however, that these sentimentalities should be so conspicuous among radicals who otherwise are uncompromisingly realistic. Sex, as modern psychology has revealed, has its roots deep in the unconscious life of the individual. We can more easily change our ideas than our emotional reactions. It is no exaggeration to say that, in one way or another, we are the slaves of our neurons. While we often find phenomenal changes in the intellectual convictions of a man, we rarely discover anything resembling an emotional revolution. A man’s emotional patterns represent a certain equation that varies within a very narrow radius. A sluggish personality, under the compulsion of intellectual conversion, may proffer different arguments, but he will not become dynamic. In the first place, the tendency of a sluggish personality to be converted is slight. A dynamic personality, on the other hand, cannot be made static by any futilitarian forensic. These characteristics are determined by the internal chemistry of the individual. Of course, the fact that psychological types are the product of early environmental stimuli, even interuterine influences, and not the direct derivative of the germ-plasm, is essential to any scientific interpretation of behavior. With our knowledge of psychological types, therefore, we are in a position to understand more satisfactorily than before the subtleties of contradiction that we find in many of our contemporaries, radical as well as liberal. In this way we can explain the capacity of men to dichotomize their approach to reality, focusing a radical lens upon one phase, and a conservative one upon another. From those things that have been touched by a myriad associations, inwrapt in the personality, as it were, by experiences too numerous to recall, it is most difficult to escape. We radicals want life to move in sharp, simplified patterns, but it does not. The whole Marxian conception, for example, explains life in terms of flux, economic change being its fundamental determinant. Yet when we consider the aspects of economic change, the manifold ramifications in the structure of society, we find cultural-lags, vestigial tendencies, contradictory criss-crossing conceptions that take us far afield from their fundamental source in order to understand their subtler manifestations.

In illustration of this it would not be difficult for me to take a certain radical in America who is well known for his courage, clarity and vigor, and show the traceries of religious conviction still in the background of his personality. This is not mentioned in terms of detriment, but rather in an attempt to show how contradictory reactions can fuse within a personality that is at once sentimental and radical. However intellectually man endeavors to harden himself, he cannot escape the exigencies of his own nervous system. Only in times of mob crisis possibly may his individual equation be altered. It is in the study of these individual differences, especially among our leaders, that we shall be able to strengthen our radical movement.

After all, we must remember, if we are to cite names, that both Radek and Trotsky believe that “the psycho-analytic theory of Freud…can be reconciled with materialism.”3

Our attitudes toward sex and family life are closely bound up with complexities of emotional reaction that have been nurtured since childhood. We have been forced to view sex in a certain fashion, and sex-relations have taken on certain forms that are often justified with an intelligence that is conservative rather than radical. We permit freedom of speech about things economic, but with things sexual we suddenly become silent. Destroy the old economic system, but do not worry about the old sex-system and the old family-mores. Although we know that it is within the shell of the old society that the forms of the new find their first fumblings of expression, we insist upon consideration only of the economic, and recommend reticence in reference to the moral.

The extremity to which this boxed-in attitude prevails is to be discovered in the reactions of radicals to any analysis of the moral situation that goes beyond the conceptions of sex-relationships that they learned in early adolescence. In reply to an article entitled The Sexual Revolution which was printed in the previous issue of THE MODERN QUARTERLY, Mr. H.M. Wicks burst into a devilishly amusing diatribe which he entitled (he should have done so bashfully, I am sure,) An Apology for Sex Anarchism. And this was all done because Darmstadt, who Mr. Wicks later discovered lived in Cambridge and not in Baltimore, hazarded the conclusions that our contemporary radicals keep their journalistic “columns as sweet and clean for its young and tender revolutionary readers as the Sunday-school Times.” And Mr. Joseph Freeman, who suddenly hears of a debate which he missed, entitled Is Monogamy Desirable? becomes alarmed, and inclining to satire that would have teased Polyanna, describes it as Monogamy vs. Lechery.

It is dangerous, as you see, to touch upon the sex question in a serious manner–in America. The conservatives denounce the practice as revolutionary, and the revolutionaries attack it as decadent. Neither can escape the influence of their early environment.

II

If the U.S.S.R. heeded these various and volcanic comments upon sex-attitudes, conceived in these tormented States, it might, perchance, be forced to change its policy toward the sex-problem. In the U.S.S.R., on the other hand, there is a definite attempt to meet the problem of sex as well as the problem of society with a realistic candour.

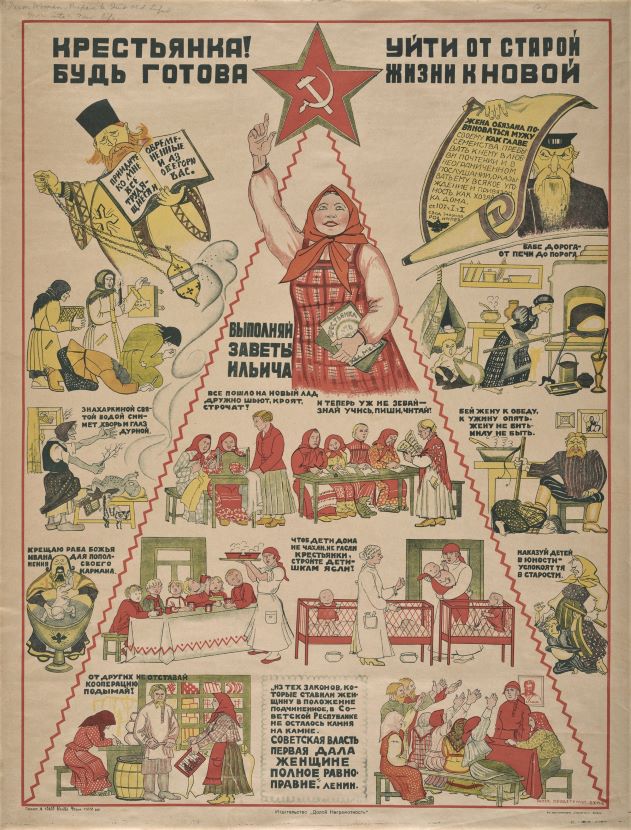

The sensational accounts of the “communization of women in Russia” announced by American journalists make one wonder if these gentlemen suffer from the dream-delusions of paranoia or the wish-fulfillment of an otherwise harassed brain. Marriage in the U.S.S.R. is a civil function, as in every other country, with regular registration as the customary part of its procedure. The ecclesiastical aspects of marriage, however, which once perfumed the whole ceremony with the incense of superstition, have been destroyed. Marriage can no longer be a source of income to the priest. The new revision in the marital code establishes eighteen years as the age at which both sexes can marry. The laws in reference to marriage have been ordained for the protection of the woman and not for the convenience of the man. Woman has been emancipated from her subordination to man which she still suffers in the civilized, western world. Lenin’s own words upon the point are signal:

“It is a fact that in the course of the past ten years not a single democratic party in the world, not one among the leaders of the bourgeois republics, has undertaken for the emancipation of women the hundredth part of what has been realized by Russia in one year. All the humiliating laws prejudicial to the rights of women have been abolished; for example, those which made divorce difficult, the repugnant rules for inquiring into paternity, and other regulations, relating to ‘illegitimate’ children. Such laws are in force in all civilized states, to the shame of the bourgeoisie and of capitalism. We are justly proud of our progress in this field. But as soon as we have destroyed the foundations of bourgeois laws and institutions we arrived at a clear conception of the preparatory nature of our work, destined solely to prepare the ground for the edifice which was to be built. We have not yet come to the construction of the building.”

In line with these principles, the woman is the equal of man in every activity and in every organization in life. When she marries she is still a free woman; marriage, the domestic code clearly asserts, “does not establish community of property between the married persons”; and in another section we discover that “change of residence by one of the parties to a marriage shall not impose an obligation upon the other party to follow the former.’ The surname of the children may be that of either the wife or the husband, depending upon the voluntary decision of the couple. In the matter of children, a responsibility rests upon the man that cannot be evaded. In case of divorce, which we shall treat of in more detail later, a third of the man’s salary is requisite for the support of each child. In the case of more than two children, however, the man is allowed to retain one-third of his salary for his own support.

Now what is revolutionary about the Soviet marital system? Let us, for a moment, quote Kollontai, one of the leading communist thinkers, upon this problem:

“It is necessary to declare the truth outright, the old form of the family is passing away; the communist society has no use for it. The bourgeois world celebrated the isolation, the cutting off of the married pair from the collective weal; in the scattered and disjointed individual bourgeois society, full of struggle and destruction, the family was the sole anchor of hope in the storms of life, the peaceful haven in the ocean of hostilities and competitions between persons. The family represented an independent class in the collective unit. There can and must be no such thing in the communist society. For communist society as a whole represents such a fortress of the collective life, precluding any possibility of the existence of an isolated class of family bodies, existing by itself, with its ties of birth, with its female egoism, its love of family honor, its absolute segregation.

“Already ties of blood, of birth, and even of the relationship of conjugal love, are weakening in our eyes; in their turn there are growing, spreading, and deepening new ties, ties of the working family, the profound feeling of comradeship, of solidarity, of community of interests, the creation of a collective responsibility, of a belief in the collective welfare as the highest moral-legislative good.”

Then, in another place, and this should interest our radical friends who are so skittish when confronted with the realities of sex, she states:

“Can the short duration, the informality, the freedom of the relation between the sexes be regarded, from the standpoint of working humanity, as a crime, as an act that should be subject to punishment? Of course not. The freedom of relation between the sexes does not contradict the ideology of communism. The interests of the commonwealth of the workers are not in any way disturbed by the fact that marriage is of a short or a prolonged duration, whether its basis is love, passion, or even a transient physical attraction.

“The only thing that is harmful to the workers’ collective state and therefore inadmissible, is the element of material calculation between the sexes, whether it be in the form of prostitution, in the form of legal marriage the substitution of a crassly materialistic calculation of gain for a free association of the sexes on the basis of mutual attraction.”

Of course, if we merely wish to refer to radical literature, such statements as those of Kollontai are not new; whatever newness they have is in the fact that for the first time in history a workers’ state is in operation which, in its direction, will endeavor to translate radical theory into social practice. Engels in The Origin of the Family had declared that:

“The emancipation of women is primarily dependent on the reintroduction of the whole female sex into the public industries. To accomplish this, the monogamous family must cease to be the industrial unit of society.” (page 90)

And in the way of prophecy, in another place he asks:

“Will not this be sufficient cause for a gradual rise of a more unconventional intercourse of the sexes and a more lenient public opinion concerning virgin honor and female shame? And finally, did we not see that in the modern world monogamy and prostitution, though antitheses, are inseparable and poles of the same social condition? Can prostitution disappear without engulfing at the same time monogamy?”

In other places, it is true, Engels is somewhat contradictory: for example, in one place in the essay he argues that “since sex-love is exclusive by its very nature–although this exclusiveness is at present realized for women alone–marriage founded on sex-love must be monogamous,” and then on the same page admits that “the duration of an attack of individual sex-love varies considerably according to individual disposition, especially in men,” and on the next page, discussing the moral world once capitalism has been overthrown, he concludes that “once such people are in the world they will not give a moment’s thought to what we today believe should be their course. They will follow their own practice and fashion their own public opinion about the individual practice of every people—only this and nothing more.”

Bebel and Bax were even clearer and more definite in their vaticinatory declarations. In Woman and Socialism, Bebel wrote, long before Kollontai ever published her Family and Communism or made her address on The Fight Against Prostitution, that:

“In the new society woman will be entirely independent, both socially and economically. She will not be subjected to even a trace of domination and exploitation, but will be free and man’s equal and mistress of her own lot.

“In the choice of love she is as free and unhampered as man. She woos or is wooed, and enters into a union prompted by no other considerations than her own feelings. The union is a private agreement, without the interference of a functionary, just as marriage had been a private agreement until far into the Middle Ages. Here socialism will create nothing new; it will merely reinstate on a higher level of civilization and under a different social form what generally prevailed before private property dominated society.

“Man shall dispose of his own person, provided that the gratification of the impulses is not harmful or detrimental to others. The satisfaction of the sexual impulse is as much the private concern of such individual as the satisfaction of any other natural impulse. No one is accountable to anyone else, and no third person has a right to interfere. What I eat and drink, how I sleep and dress, is my own private affair, and my private affair also is my intercourse with a person of the opposite sex.” Belfort Bax was even more challenging:

“There are few points on which the advanced radical and the socialist are more completely in accord than in their theoretic hostility to the modern legal monogamic marriage. The majority of them hold it, even at the present time, and in the existing state of society, to be an evil…”

“Socialism will strike at the root at once of compulsory monogamy and prostitution by inaugurating an era of marriage based on free choice and intention and characterized by no external coercion.”

We see, then, that Kollontai in expressing the Bolshevik attitude toward sex and the family-life did not intellectually leap ahead of her predecessors. Of course, in her former capacity in the Bureau of Public Welfare and through her influence in the woman’s movement, she was in the actual struggle of social revolution, and thus had the fire of living experience to give glow to her actual theory.

Nevertheless, Kollontai’s eloquent picture of the future sex-relations and the future family under communism have not yet been realized in Soviet Russia. As M.I. Kalinin said:

“The new law is not entirely new. It only makes a big step forward,”4

or as stated in the early edition of the code:

“Only time and experience will show how many of the provisions of this code belong to the transitional category, features which are destined to vanish with the more perfect establishment of the socialist order. In certain clauses, however, there is clearly to be discerned a conscious recognition of conditions and habits of life surviving from the old order. Such survivals are inevitable at this time when neither the economic nor the psychological transformation is complete. There are provisions respecting property and income which will inevitably be subject to obsolescence or amendment. The law of guardianship, essentially revolutionary as it is, is yet no more than a first tentative approach to the realization of collective responsibility for the care of the young. The laws of marriage and divorce still bear traces of the passing order, frank and sensible acknowledgement of the existence of certain economic and psychological conditions only to be overcome when the complete change is accomplished.”

The revolutionizing elements that are already to be discovered in the new moral attitude of Soviet Russia are to be found in the laws regarding children and divorce. There is no distinction between legitimate and illegitimate children, married or unmarried mothers. All children and all mothers are equal before the law and in society. This is an important economic and moral consideration. It means that marriage no longer possesses the magical aspect which was once its heritage. Under the Tzar, for instance, if a man and woman lived together for thirty years, and had ten children, the couple could not appear as man and wife unless a church marriage was effected, nor could the children appear as progeny of the father. According to the old Russian law this man was not their father, and in the bureau of births these children were entered as born illegitimately, of an unknown father. The woman had no rights to the property of the man, nor did the children; if he died intestate his property went to his relatives. In fact, according to penal statute, every woman who lived with a man, in an unmarried state, could be categorized as a “prostitute.”5 Under the Soviets all of this, as we have seen, is reversed. As S.M. Glikin wrote:

“We have no legal and illegal children. Here all children are equal, they are all legal.”6

Whether a civil marriage has been performed or not, man and woman are registered as father and mother in the bureau of births. A family according to Soviet law is “where there are parents and at least one child.”7

It should not be thought that these laws were laid down with a rigid hand by a kind of superior dictatorship. On the contrary, as S.M. Glikin says in his pamphlet entitled The New Law Concerning Marriage, Family and Guardianship:

“The All Russian Central Ispolkom decided not to sanction the new law until it could be discussed by the workers. During a whole year the new laws were discussed in factories, shops, village meetings, and military organizations…The laboring masses of the Republic discussed it with great attention…In its final form, thus, it represents the conclusions of millions of workers in cities and villages.”

The result is as Kudrin stated:

“The new code of marriage and family is not only a law forged out by the hands of many millions of laboring people, but it also reflects the spirit of the new revolutionary state.”

The other revolutionary element in the new Russian mores is in the facilitation of divorce. The advance made in this field is most significant. It is as close an approach to the freedom of sex-relations predicted by Kollontai as could be attempted in present-day Soviet Russia. Divorce can be gotten by mutual consent, without the paraphernalia of bourgeois justice which necessitates adultery, cruelty, or desertion as the sufficient reason. Incompatibility is a valid ground for divorce.

(The mutual consent of the husband and wife or the desire of either of them to obtain a divorce shall be considered a ground for divorce.)

It is when one recalls the divorce situation under the Tzar, with the Church willing to dissolve marriage only upon the issue of adultery, that one realizes what a tremendous advance the divorce laws of Soviet Russia signify. In the pre-revolutionary days divorce was accessible only to the opulent. Today it is the liberating device of every worker and peasant in the Republic. The petition for a divorce can be made in writing if the parties do not wish to appear originally in person,

(A petition for the dissolution of marriage may be presented orally or in writing and an official report shall be drawn thereon)

and shortly thereafter the court will “set the day for the examination of the petition and shall give notice thereof to the parties and their attorneys.’ The procedure is brief and expeditious. The attitude of the judges is humanitarian rather than legalistic. The chief problem involved in a divorce is that of the children. If there are no children, delay is infinitesimal. If there are children, it is the woman and children who are primarily protected in the details of the divorce-grant. The man must make adequate provision for them, depending upon the state of the mother and the number of the children, before the petition for divorce will be confirmed.

That Soviet Russia is in the advance of the rest of the world in its attitude toward sex, marriage, and divorce will not be doubted by any progressive mind. Already it has destroyed many of the trammels of bourgeois morality and the bourgeois marital code. It has freed the sexes of the religious taboos that for so many centuries made of the marital institution a lifelong lasso and impediment to progress. As Paul Blanshard wrote upon his return from the U.S.S.R., the youth there “discuss sex-relations, abortions, and love with the candour of obstetricians.” Birth control, for example, is not the hidden thing that it is in the United States. Birth control literature is plentiful and authentic. At a railroad station I picked up a pamphlet on birth control (entitled Prevention of Childbirth, by Dr. M.Z. Shpak), which sold for a pittance and had already gone through numerous editions. In the pamphlet were described a number of methods to prevent conception, with admonitions as to certain methods that experience had proven precarious. It is part of the duty of a physician to instruct his patients in the proper methods of birth control. In fact, in the protocol of the Conference of Obstetricians in Moscow, October 21, 1923, it was stated that it was “the duty of an obstetrician to teach the female population to be able to use a harmless contraceptive method, wherever pregnancy is either impossible or unwanted by a given person.” Abortion has been made legal,8 and is performed by the state physicians. Between 1922-24 more than 55,000 legal abortions were performed in the Russian district hospitals. These are but a few of the progressive manifestations of the new attitude towards morals and marriage in Soviet Russia.

What must be emphasized is that the whole approach of the Russian communists to the problems of sex and morality–in fact, to all problems–is wonderfully realistic. In facing a problem such as prostitution, for instance, there is no attempt to obscure its extensity and danger, or deny its existence. The sentimentality, which we referred to in an earlier part of this article, that is manifested in the statements of those who claim there is no prostitution in Soviet Russia, is ridiculed in the very statistics of the Central Ispolkom. One of the main problems, in the struggle with prostitution, as we stated in the report published in the Izvestia (of the Central Ispolkom, November 11, 1926) is that involved in the battle with the brothel-keepers. In thirty states in one year 715 houses of prostitution were opened, 264 in state cities, 159 in cities, and 281 in country locations. The cities most deeply infested with this menace are, in order of seriousness, Moscow, Leningrad, Samara, and Stalingrad. This report was made by Kiselev, the chief of the militia. It is what has been done to eradicate this evil which is important. In the first place, the problem has been subjected to profound investigation and study. One of the first facts discovered was that the unemployment of single women was one of the greatest dangers. Over 32% of the prostitutes in Moscow, for instance, are by occupation house-workers (Izvestia, November 11, 1926). Consequently, a resolution has been passed which declares that, in the event of unemployment, “single women should be ‘laid off’ last. This is a remarkably intelligent advance in social therapeutics. In addition, numerous homes have been organized all over Soviet Russia for the reformation of prostitutes. These homes give the prostitute shelter and food, and attempt to teach her a trade. In this way, the economic factor has a direct influence in the moral equation. The Union of Public Health has also organized homes where women out of work can sleep at nights. This likewise is an intelligent social tactic. A project has also been worked out by the Union of Public Health to organize a colony “with a labor régime for 3,000 prostitutes.” As a result of these measures, H.A. Semaskho, Commissar of Public Health, reports that prostitution is on the decline–in fact, that it is now less than in the prewar period.

In conclusion, we may say that in the U.S.S.R. we have already the beginnings of a morality that is in advance of the rest of the world. If the free-relations so exquisitely apostrophized by Kollontai and Carpenter have not yet been achieved, the approach is unquestionably in that direction. The ecstasy of sex-contact, the joy of erotic communion, are regarded as private to the participants, and not subject to social intervention and restriction. It is only when children are involved that sex-relations really become a matter of social interest and consideration. This is apparent from the very structure of the new Russian mores. Couples who live together without marrying are as amply protected by the law as those who marry (New Law Concerning Marriage, Divorce and the Family— S.M. Glikin), and the absence of social stigma gives to their lives the same opportunity and freedom as are possessed by the more conventional and unadventurous. The children of unmarried unions are treated the same as those of married. The freedom of divorce is strange paradox, an incentive to marriage. The old monogamous marriage has disintegrated. The new marriage is as free an institution as could be contrived under the changing conditions of Soviet Russia. “Soviet divorce is so free,” writes S. M. Glikin (ibid.), “that if one of the parties wants a divorce it is enough to announce it in the Ispolkom. The other of the spouses is informed about the divorce having taken place.” So free in fact is it that I.A. Rostovsky, writing in another Soviet pamphlet (cf., above), declares that “to give any explanations why one of the spouses wants a divorce is unnecessary…for to remain married or to dissolve the marriage depends entirely upon the desire of one of the spouses, and consequently to coerce them is impossible, and, therefore, any explanation is unnecessary.” Only in the case of children is there delay or difficulty. This freedom is equal to both man and woman. The old laws which handicapped woman in this respect are now obsolete. With instruction in the use of contraceptives and prophylactics as part of the educational life of the woman as well as the man, and abortion as a privilege and not a crime, the “unwanted” child in Soviet Russia can be largely eliminated from the errors of civilization. While it would be sheer folly to picture these new changes in the moral life of Russia as the background of a new paradise, it is the direction toward which they point that holds for us such great hope for the ultimate liberation of man.

NOTES

1. The Red War on the Family. Samuel Saloman.

2 Cf. Augur: Soviet versus Civilization. Appleton, $2.50.

3. Literature and Revolution-Trotsky, page 220.

4. Quoted from Marriage and Family—A. Prigadov-Kudrin: Soviet publication.

5. Marriage and Family-A. Prigadov-Kudrin.

6. The New Law Concerning Family, Divorce, and Marriage.

7. Ibid.

8. For more details in reference to birth control and abortion in the U.S.S.R. see the author’s forthcoming book on Morality and Marriage.

Modern Quarterly began in 1923 by V. F. Calverton. Calverton, born George Goetz (1900–1940), a radical writer, literary critic and publisher. Based in Baltimore, Modern Quarterly was an unaligned socialist discussion magazine, and dominated by its editor. Calverton’s interest in and support for Black liberation opened the pages of MQ to a host of the most important Black writers and debates of the 1920s and 30s, enough to make it an important historic US left journal. In addition, MQ covered sexual topics rarely openly discussed as well as the arts and literature, and had considerable attention from left intellectuals in the 1920s and early 1930s. From 1933 until Calverton’s early death from alcoholism in 1940 Modern Quarterly continued as The Modern Monthly. Increasingly involved in bitter polemics with the Communist Party-aligned writers, Modern Monthly became more overtly ‘Anti-Stalinist’ in the mid-1930s Calverton, very much an iconoclast and often accused of dilettantism, also opposed entry into World War Two which put him and his journal at odds with much of left and progressive thinking of the later 1930s, further leading to the journal’s isolation.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/iau.31858045478306