Veteran labor reporter Carl Haessler on the reasons for the phenomenal growth of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers in Chicago to 50,000 members in the early 1920s.

‘The Amalgamated Pushes Forward’ Carl Haessler from Labor Age. Vol. 11 No. 5. May, 1922.

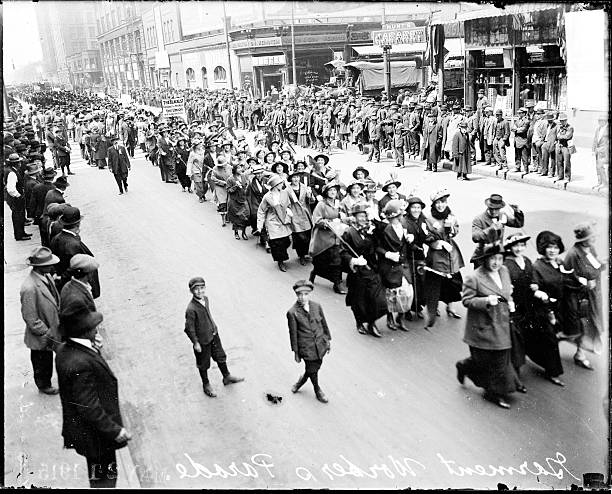

Story of the Big Clothing Workers’ Union’s Growth in Chicago–and Why

OUT of the needle trades have come many of the new tactics which labor has adopted. The Amalgamated Clothing Workers, having in mind final control of industry by the workers, have set up arbitration machinery based on consent of those doing the work. Last month they announced the establishment of a labor bank under their control. Chicago is the first city to have an Amalgamated Bank. It is there also that the 1922 Convention of the Amalgamated meets on May 8th. Here is the remarkable story of the Amalgamated’s growth in the “Windy City.”

THREE more years of peace in the men’s clothing industry in Chicago were insured when the Chicago rank and file of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America ratified the new agreement that Sidney Hillman, president of the organization, had negotiated with the Association of Chicago Clothing Manufacturers. The agreement was concluded April 4 and goes into effect May 1, when the present contract negotiated three years ago, expires.

The Union Stands Firm

Both sides claim the advantage. The union, however, with its 40,000 to 50,000 members in Chicago, has yielded practically nothing but an all round cut in wages averaging slightly under 10 per cent and has gained substantial points.

The machinery of job control, of arbitration and negotiation remains intact or is consolidated more securely than before. The union has maintained its position in an adverse period by the effectiveness of its internal discipline and of its outward unity.

During the world war a private in the American army was court-martialed for “glaring contemptuously” at a lieutenant. Since there were other charges against him the court did not find it necessary to convict him on the “glaring” indictment. In the Chicago market the position of privates and officers is reversed. It is now privates in the clothing army that bring such charges against the lieutenants, the foremen.

How Complaints Are Handled

One big room in the Amalgamated headquarters at 509 South Halsted Street is devoted to receiving complaints brought in by union members. These range from the most trivial to momentous issues of union policy. Each complaint is investigated by a union deputy as the business agents are called, and the particulars are noted on a special form. Usually a consultation with the labor manager–the business agent of the employer–settles the difficulty. If not, there are channels of appeal.

Here is a specimen complaint: “The section of pocketmakers had work left over from Friday. This work would be the start for their work today, but when they came this morning, they had to wait for work.”

The disposition of this complaint is business-like and judicial: “There is no way of proving this complaint.”

A wage complaint reads as follows: “She complains that she was hired on $32 a week but she was paid on $25 basis.”

The disposition by the union deputy scores heavily against the complaint: “There was no agreement made on $32. She was told she will be paid $25 and she admitted that.”

And here is a case of contemptuous glaring, or rather its next-door neighbor, mingled with a jurisdictional dispute: “The examiner is doing the busheling (the final loving touch given to a suit). This same examiner uses profane language to the off-pressers.”

Disposition: “The examiner was instructed not to do busheling anymore.”

But alas for the off-pressers. The charge of profanity was ignored.

The Courts of Appeal Complaints that are not satisfactorily adjusted can be carried higher in two days. If the union member believes the deputy is not acting fairly by him, charges may be brought against the deputy before the appeal committee of the joint board. The joint board is a purely internal body of the union which enforces discipline on the members. Each local elects delegates to the joint board in accordance with its numerical strength. The board’s appeal committee is subordinate to the board itself. The board bows to the general executive board of the entire organization and the executive board acknowledges the supreme will of the convention. Thus the off-pressers, for example, who objected to the examiner’s profanity, had six successive agencies within the union to whom they might have carried their case.

On the other hand, if the deputy’s ruling is objected to by the employer through the labor manager, the matter can be taken before the trade board. The trade board consists of an impartial chairman and of representatives not to exceed five in number from each side. It handles detail work of interpretation of agreements and attempts to adjust the human factors in the industry. The trade board’s rulings are usually accepted.

Resort to Arbitration

But if either side feels aggrieved there is the arbitration board. The arbitration board consists of three members: Prof. H.A. Millis, University of Chicago, impartial chairman; Carl Meyer, representing the employers; Sidney Hillman, representing the workers. In addition to being the court of last appeal, the arbitration board has wide interpretative powers and has also in the past taken legislative powers which are now expressly abolished by the new agreement.

The limitation of powers is regarded favorably by both sides because an element of uncertainty has been removed or at least reduced to a point where it can be removed, not by outside decision, but by negotiation.

Union members thus have their joint board–their police court as it were–and they have the trade board and arbitration board–the circuit and supreme courts of the industry.

In Chicago there are three trade boards. Hart, Schaffner & Marx, the first to install the arbitration machinery, have their own board, headed by James Mullenbach. The rest of the Chicago market is presided over by B.M. Squires and his associate, Thomas A. Allinson.

There is a large staff of labor managers acting for the employers and a staff of about 35 deputies for the union. The labor manager is in the unenviable position of a man who is supposed to “understand” and sympathize with the workers, but who gets his wages from the employers.

Union deputies fall into two fairly distinct categories. There is the old time dogged, shrewd, hard-hitting and respected fighter, a pioneer in the union, and there is the more suave, diplomatic, smiling younger representative, who yields gracefully only to more than regain his position a moment later.

Labor managers would classify Samuel Levin, general manager for the Amalgamated in Chicago, in the first group. No one doubts the integrity of any of the Amalgamated representatives. The harshest criticism is that some of them are “narrow.”

To this Levin answers: “No doubt this is true. The same criticism holds of the labor managers. We are constantly improving our personnel.”

The New Employment Machinery

Levin also admits that the employment machinery of the union is not yet what it should be. Under the system of union job control, the employer who wants help notifies the union. The union sends over an applicant from its waiting list who is then put on two weeks probation. If he is acceptable during that period he must be retained by the firm until he is dismissed for just cause, subject to review by the union deputy and the trade board, if necessary. The employers complain that frequently the wrong kind of man for the job is sent over. They say the union should have a better line on the special ability and training of its members and fit them into jobs more accurately. Levin does not deny this but says the machinery is new and is being constantly improved. One of the union victories scored in the new agreement is the retention of the two- week probation period. The employers wanted the probation extended to four weeks, or practically one-third of the busy season.

Hear It Grow!

Amalgamated history in Chicago dates back over 10 years. Although the first general agreement was signed in 1919 for a three-year period, earlier separate contracts had been made. Hart, Schaffner & Marx began their pioneer labor management in 1910.

The Amalgamated grew rapidly from about 3,000 members at the start to 40,000 in 1919. The present membership fluctuates with market conditions but averages between 40,000 and 50,000. Membership dues in Chicago are $2.00 a month flat, except for cutters and trimmers who pay $2.2 because their local treasury gets a larger rebate from the general treasury. A membership book issued in any Amalgamated town in the country is universally valid. Organizers work on a strict salary basis. They are reaching out constantly from Chicago in the attempt to sew up the clothing field on a union basis.

Clothing manufacturers in Chicago affected by the agreement number over 200, not counting sub-contractors, and represent a capital estimated at far above $100,000,000. In 1917 Hart, Schaffner & Marx alone did a business of $75,000,000, Amalgamated officials say.

It is generally believed that the big firms are more friendly to the union than the smaller concerns. This is probably because the big fellow I can adapt himself to union requirements regarding the equal distribution of work to union members and to union job control more advantageously than can the smaller fry. The attempt of the manufacturers to wrest job control from the union failed.

A feature of the agreement is the inclusion of a provision for enabling the trade to deal with the unemployment which used to be chronic because of the seasonal nature of the industry. Although reduced to some extent unemployment is still a severe blight.

Nothing specific has been done toward establishing the unemployment fund proposed by Leo Wolman, chief, research department of the union, but the Chicago union is permitted to bring the matter up before the expiration of one year and to terminate the entire agreement if no settlement is reached. Wolman’s plan would make unemployment a charge on the industry instead of on the worker, making the employer responsible financially for finding work for his employees. The union would probably consent to a modification which would put part of the expense upon the worker.

Thousands for Education

In addition to its strictly economic activity, the Amalgamated in Chicago as elsewhere devotes time and money to education and recreation. The Chicago union spends $20,000 to $30,000 a year on lectures, concerts, entertainments and its own library. The national organization donated $100,000 to the steel workers in the great steel strike of 1919 and has collected $175,000 up-to-date for Russian relief. The Los Angeles sanitarium for consumptives has benefited to the extent of $15,000.

These “extra-curricular” activities have helped to endear the union to its members. The Amalgamated has profited immensely from a leadership that is not limited in vision to the immediate job. That is one element in the strength which enabled it to negotiate the new agreement.

In presenting their twelve demands on February 14, the manufacturers complained that, “whereas the spirit of the agreement calls for the most cordial cooperation of the union in meeting the situations employers have to face, the efforts to adopt the administration of business to the unprecedented conditions of the last two years have met with persistent obstruction and annoyance, with the result that the agreement has become in practice not an instrument of cooperation but one of repression and legal technicalities.”

The Twelve Demands

This charge was little more than a wordy barrage, like the majority of the twelve demands, as a comparison of them with the final agreement will show.

The manufacturers demanded:

1. That selection of workers must be entrusted again to the employer. In the agreement selection remains with the union. Probation is to last four weeks instead of two. It remains at two.

2. That hiring and firing must become a prerogative of the employer. The union, however, retained its job control.

3. That equal distribution of work must yield to efficiency. In the outcome “efficiency” lost.

4. That entire freedom of management be conceded to the employer. The agreement continues to safeguard the worker.

5. That piece work for trimmers be restored and that week-work standards be enforced more vigorously. Nothing doing in the agreement.

6. That piece work be extended at will. No luck.

7. That the 48-hour week displace the 44-hour week. No displacement.

8. That wages be cut 25 per cent. Wages actually were cut 10 per cent, with a minimum of $39 and $35 a week for cutters and tailors respectively.

9. That peak piece rates in certain shops be trimmed down. Lost in the shuffle.

10. That holiday pay be abolished. Not mentioned, but subject perhaps to supplementary negotiation.

11. That final examiners (inspecting tailors) be not included in the agreement. Motion lost.

12. That necessary administrative changes for the better enforcement of rules by the employers be permitted. Laid on the table.

“The new agreement,” the Amalgamated announced, “preserves for the Amalgamated and its 50,000 members the essential conditions for which it had fought for 10 years, and which it won throughout the city of Chicago in 1919. It is of great significance to the country that this momentous experiment in the peaceful adjustment of industrial disputes will continue as an example for other industries.”

Industrial peace seems directly proportionate to the power of unions to enforce it.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v11n05-may-1922-LA.pdf