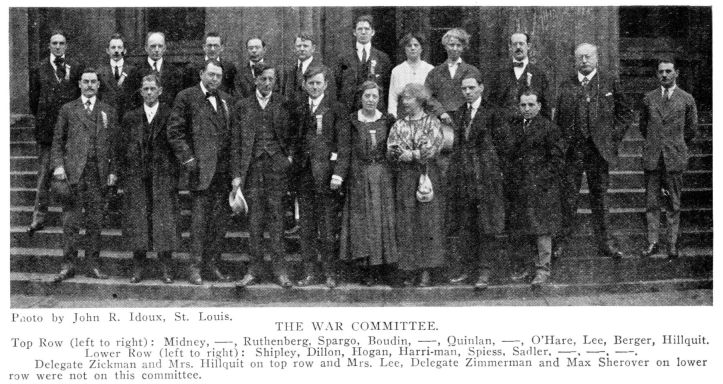

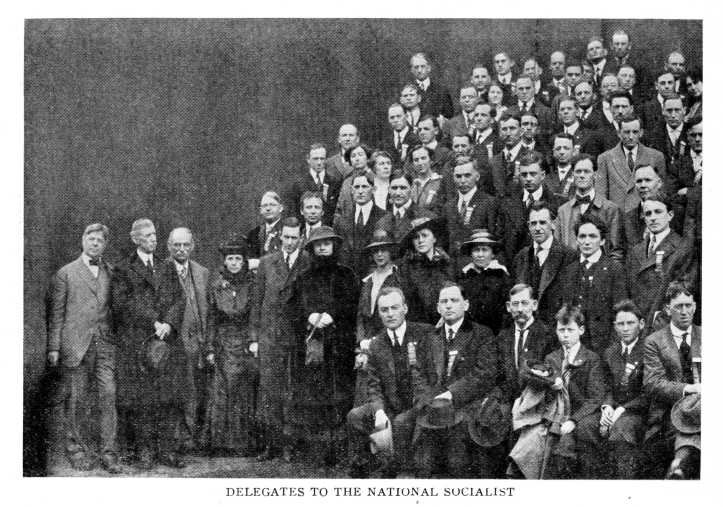

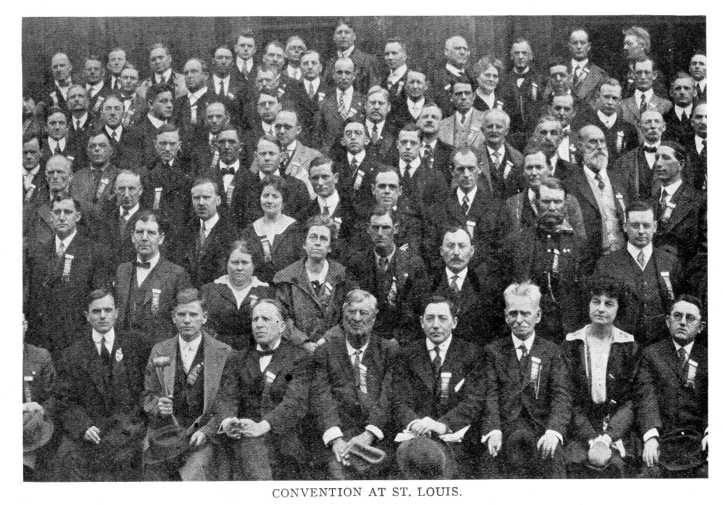

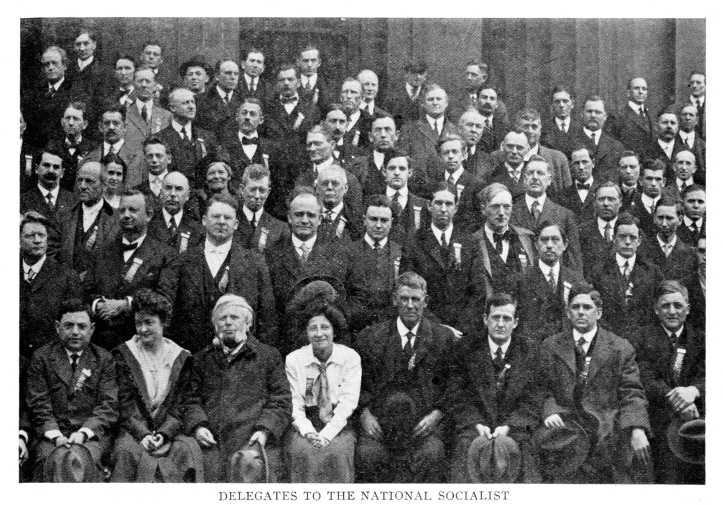

Boudin’s article on 1917’s Emergency Convention will be of interest to all students of U.S. Socialist history. The week-long emergency meeting in St. Louis to discuss the Socialist Party’s attitude to US involvement in World War One was attended by 200 voting delegates (pictured in the story) as well as representatives of eight Language Federations, 141 of the delegates voted for the anti-war statement authored by representatives of the center, left and right (Morris Hillquit, C.E. Ruthenberg, and Algernon Lee). Louis B. Boudin tenaciously held to his ‘third’ position, viewing the majority position as a false agreement. The pro-war right was routed and split to found their own short-lived National Party.

‘The Emergency National Convention of the Socialist Party’ by Louis B. Boudin from Class Struggle. Vol. 1 No. 1. May-June, 1917.

The National Convention of the Socialist Party just held at St. Louis was long overdue. The Socialist Party of this country is the only Socialist party in the world that we know of that has not held a convention in five years, and the only one in any country where such a convention could be held that has not held one since the commencement of the Great War. The ruling powers within the party do not like conventions. Like all ruling powers they are opposed to “agitation” and “unnecessary discussion.” And conventions have the bad habit of being attended by “agitation” and “unnecessary discussion,” both inside the convention as well as outside of the same. Hence, the guiding rule of our party management–avoid conventions by all means.

But, as is the case with all forces artificially repressed, there finally came a time when the demand for a convention could be repressed no longer, and we were given a convention. And, as is usual in such cases, the convention came upon us like some elemental force, in a haphazard and disorderly fashion, without any chance for a proper discussion by the membership of the work which it was to do, and, in many instances, without the membership having a voice in the selection of delegates.

The convention itself largely reflected the circumstances which brought it about, and the manner in which it has been called together: It showed a considerable excess of passion and resentment over clearly thought out principles and policies. There was in evidence an enormous amount of passionate hatred of war, and strong resentment against party leaders, here as well as abroad, who have led, or were ready to lead, the proletarian masses into the shambles of capitalism. But, I am sorry to say, very few signs of a carefully considered theoretical position on the subject of war and peace, or of a well thoughtout rule of conduct which the working class of the world could apply in practice when confronted with this problem. The deliberations of the convention were, therefore, more a matter of groping blindly by instinct than of calm judgment and logical reasoning. That under such circumstances it is particularly human to err goes without saying; and we need not, therefore, be surprised to find many who were seeking a revolutionary mode of action catching at empty but glittering phrases.

It was only natural that such a convention should fall a prey to the machinations of the party bureaucracy which has led it into the wilderness of barren opportunism and which has practically destroyed the party during the past two and a half years by not permitting it to find itself and to take a decided stand on the questions which have agitated the world since the outbreak of the Great War. And it did. With the result that we are now exactly where we were before the convention met, with no definite position on the burning questions of peace and war–the relation of nationalism to internationalism, of the class struggle to national struggles, of the defence of small nations, or how far class-conscious workers may join hands with other social groups in defence of or for the furtherance of democracy. All of these questions were studiously avoided by the astute managers of the convention, and the declaration adopted by it has therefore nothing to say on these momentous subjects–being nothing better than an ill-assorted collection of soap box immaturities and meaningless generalities; assertions which cannot be defended when taken literally, and which must therefore be taken with a mental reservation which renders them utterly worthless as a definite statement of position; all trimmed and garnished with qualifying adjectives which makes their apparent meaning nothing but hollow pretense. In short, instead of a definite statement of position we have a document which will mean one thing to Berger in Milwaukee, another to Harriman in California, still another to Hogan in Arkansas and yet still another to Lee in New York.

Only one thing is clear and unmistakable about this document: it is as clear a pronunciamento against the war declared by the United States against Germany as could possibly be desired. This practical declaration is, however, in glaring contradiction to the theoretical basis upon which it pretends to rest, and is rendered valueless for all practical purposes by the absence of a solid foundation of Socialist principle. We have had similar declarations in the past, but they had no practical effect whatsoever because they suffered from the same vice. And signs are not wanting that the present declaration will fare no better. In fact, it has already been flagrantly and ostentatiously violated by our representative in Congress, with the usual result: the party has swallowed the bitter pill with a wry face, but the leaders of the alleged majority who were so loud-mouthed in their pretended revolutionarism in St. Louis keep mum when it comes to real action. It is the fate of all such hypocritical pronunciamentos that their sponsors should not then defend them, whenever such defence might lead to an exposure of the real motives which actuated them in adopting it.

I spoke of the leaders of the “alleged majority” when referring to those who framed the so-called “majority report” of the St. Louis Convention. And I want it clearly understood that the declaration which was adopted at that convention does not represent the views of a majority of the delegates to that convention, and would at no time have commanded the support of a majority of the delegates had the matter been squarely presented to them.

The fact is that the formulation as well as the adoption of the so-called “majority report” was the result of a series of political tricks and manoeuvers such as has seldom been seen before at a Socialist convention.

Leaving out minor differences of opinion, the delegates to the convention formed three main groups: (1) In the first place there were those who were uncompromisingly opposed to the co-operation of the working class with any ruling class under any circumstances. They took their position on the class struggle, which to them meant the opposition of internationalism to nationalism, in the sense that Socialists have neither the duty nor the right to defend their nation because it is theirs, disavowing any common interest between the capitalists and workers of any nation as opposed to any other nation, which could be asserted or defended in war. As a consequence they were in favor of condemning the participation by Socialists in any war declared and prosecuted by the ruling classes. This meant, of course, the taking of a strong position against supporting the present war by the United States against Germany and a readiness to fight it with all weapons at their command. It also meant the condemnation, express or implied, of the support which the European Socialists, particularly those of Germany, gave to their governments in the present war.

(2) Then there were those who believed that there was no opposition between nationalism and internationalism; that internationalism was based on “enlightened” nationalism; that nations and national cultures must, therefore, be preserved; and that the working class of any given nation had certain national interests of a material and spiritual kind in common with the ruling classes of that nation, which it is to its interest and sometimes its duty to defend. They took the position that the European Socialists were justified in supporting their governments in the Great War. But they were opposed, for various reasons, to the present war, and were in favor of the Socialists of this country carrying on an energetic campaign against “our” war, provided the means employed are legal and respectable.

(3) And, finally, there were those who agreed with those in the second group on all questions of principle, but differed with them. on the practical question of attitude to the present war here in this country. Their main contention may be summed up in the assertion that “what’s sauce for the goose is sauce for the gander”–that if the European Socialists had the right to change their tactics after the war had become an accomplished fact, giving up “useless and barren opposition” in favor of a “constructive” policy, the American Socialists had the right and duty to do likewise. Their position to the war, both in Europe as well as here, could be summarized as follows: The war is a fact which we cannot change. It is here against our wishes, but that does not change the fact of its being here. To attempt to oppose it would not only be useless, but against the interests of the working class of this country as well as against the interests of the nation. We cannot possibly desire the defeat of this country–a thoroughly democratic country–by any other country, and particularly not by an autocratic country such as Germany. Such a defeat would greatly injure the material and spiritual interests of the workers of this country. An attempt to hamper the prosecution of the war would, in addition, alienate from us the masses of the people of this country, so that Socialism could not make any headway in this country for probably a generation to come. The only “sane” and “practical” thing to do under the circumstances is to adopt a “constructive” policy looking towards the protection of the interests of the workers in the manner in which the war is prosecuted and while it lasts.

The three groups were about equal in strength. Or, if a nearer approximation be attempted it would perhaps be a correct estimate to say that the third, or “pro-war,” group could muster on a straight issue about fifty votes, or one-fourth of the convention, while the remainder was about equally divided between the other two groups.

Under these circumstances, it is quite evident that no majority could be found in the convention for any declaration which attempted to state principles as well as lay down a policy, and which at all attempted to be consistent and free from contradictions. The “pro-war” party could agree with the “center” on a declaration of abstract principles, but not on an attitude towards the American war. The “center” and the “radicals” could agree on the attitude towards the war “in America,” but not on a declaration of principles.

That is to say, if the issues had been made and kept clear, and people were honest with themselves and with others. But then that would be against all the rules of “politics.” What is the use of having “astute diplomats” and “clever politicians” if not for the purpose of making “combinations” where no unanimity of opinion exists, and so muddle the issues by the use of “judicious” but meaningless phrases, as to catch the unwary? And so the politicians and diplomats in the convention set about making “combinations,” and their ink-splashers set about patching up a document which should make as much noise and say as little as possible.

The results were surprising–to those who have never seen these things at work. When the Committee on War and Militarism opened its sessions it was decided to begin with a general discussion of principles. During this discussion Berger, Harriman and Hogan expressed views similar to those of Spargo, Berger going to the extent of expressing a desire that Spargo should be entrusted with the drawing up of the statement of principles, as he was sure Spargo could express his views better than himself. But in the end all three were found among those who signed the “majority report,” while Spargo seemingly stood alone in the committee with his views. During the same discussion Berger called the members of the committee who did not agree with his views on nationalism “anarchists” and declared that he did not care to belong to the same party with them. Their statements to the effect that they had no nation to defend elicit from him an angry declaration that they were mere brutes who would not defend their wives and daughters, and that they therefore deserved not to have a nation, wife or daughter, etc., in his well-known jingoistic style. But in the end, he and some of the ultra-radicals were found to belong to the same “majority,” and signing a document which purported to condemn all defensive warfare.

The result of “diplomacy” used between the opening session of the committee and its final session was that a committee which seemed to stand with reference to the three groups above mentioned, as six-five-four-turned out to stand three-eleven-one.

The “diplomacy” which was so efficacious in committee was not less so in the plenum of the convention. Instead of dividing 75-75-50, which was the approximate strength of the three groups, it divided, at the crucial moment, into 31-140-5.

Of course there were no conversions. Berger did not change his well-known views, which made him applaud Germany’s invasion of Serbia and demand our own invasion of Mexico. Nor did Harriman and Hogan or any of their followers become radical internationalists between the opening of the convention and the adoption of the “majority report.”

What happened was this: The “pro-war” element were given to understand that the political exigencies of the hour within the Socialist party demanded that the center and the right should combine to beat the “common enemy,” to wit: the uncompromising radicals. This they could do without any real loss of position, as they could always send out a statement of their own to be voted on by the membership. It is true that that involved the rather absurd situation of the members of a “majority” sending out a minority–proposition after the majority–proposition for which they voted had been adopted. But then, “politics is politics.”

At the same time the majority-draft–for now that the combination was made it had a majority behind it–was so “doctored” up as to catch some unwary radicals, thereby making the “majority” more impressive. And some radicals–about one-half of those present and voting–were caught by the false sound of the majority-draft and the promise held out to them that they would be permitted to improve it by amendment. A promise, by the way, which was not kept. The radicals soon discovered their mistake and raised a fuss, but it was too late.

The divisions caused by the attempts of the radicals, when they woke up to the situation, to amend the majority-draft showed that more than one-third of the delegates were seriously dissatisfied with the draft because it did not express their radical position. The “pro-war” substituted sent out by the Spargo-Benson group contains the signatures of nearly one-third more of the delegates. Which proves conclusively that the so-called “majority report” was no majority report at all, and that it was adopted by trick and chicanery–nearly one-half of those voting for it not being for it at all and voting for it merely as the result of a temporary unholy alliance brought about by the machinations of politicians to create an apparent majority where there was none.

It may be added here that the character of the “arguments” used in piloting the “majority” report through the convention was in thorough keeping with the character of the report itself and of the combination which was chiefly responsible for its adoption.

Of the other work of the convention little good can be said, with one notable exception, the repeal of the famous Section Six. In his opening address as temporary chairman of the convention, Hillquit said, in contrasting conditions in 1912 and to-day:

“At no time has a national council of our party met under more critical conditions or faced a more serious task and test than we do here to-day.

“When the chairman’s gavel fell upon our last convention, on May 18, 1912, our organization was at the zenith of its youthful vigor. Our movement was alive with the spirit of buoyant enthusiasm and the men and women in it were alive with the joy of struggle and confidence of conquest.

“Within a few years we had increased our membership to over 125,000, represented by about 5,000 live and active locals. We had increased our press to about 300 organs. We were flushed with our first great electoral victories in a number of cities and in legislative bodies, and we had just opened the doors of the National Congress to the first Representative of our party. Socialism seemed to be in the air. The Socialist movement was militant and triumphed. We saw nothing but growth and victory ahead of us.

Comrades, it will serve no good purpose to close our eyes to the fact that our party and our movement have gone backward since 1912. We have lost members. We have lost several organs of publicity. We have lost votes in the last election. And, worst of all, we have lost some of that buoyant, enthusiastic, militant spirit which is so very essential, so very vital for the success of a movement like ours.” (Applause.)

If the delegates paid any attention at all to the speaker they could not help thinking, when listening to these words, that the downward march of the movement in this country dates precisely from the time “when the chairman’s gavel fell upon our last national convention on May 18, 1912;” and that the speaker and his friends who controlled that convention were in no small degree responsible for the disorganization and decay which set in upon its close. The epitome and symbol of that unfortunate convention was Section Six. Within one year after its adoption fully one-third of the 125,000 members of the party left in disgust, and despondency took the place of the buoyancy and enthusiasm which reigned before. It took some years before this came to be acknowledged. But acknowledged it was at last, and Section Six went, unsung and unlamented.

The other work of the convention was of a decidedly different character than the repeal of Section Six. The repeal of Section Six was a frank, if belated, acknowledgment of a mistake once made. Almost every other action was a new mistake made. The most important of these are the abolition of the National Committee and the adoption of a new platform. It must be said, however, in extenuation of these sins of the convention, that they were committed in ignorance rather than in wickedness.

The National Committee has long been a thorn in the side of our party bureaucracy. They therefore sabotaged it, and sabotaged it so successfully that it has been unable to do any positive work; and then they came before the convention and claimed that it was useless. This contention was untrue, because the National Committee still performs an important supervising function, with all the monkey wrenches that are thrown into its machinery. But the convention was too tired after the great excitement incident to the war debate, and not in a condition either physically or mentally to listen to a discussion of this subject on the merits. So it just took a guess, and guessed the wrong way. Let us hope that the membership will consider the matter more judiciously and vote down the change.

As to the platform–it is sufficient to say that it was adopted at the last session–when half of the delegates were gone and the rest were going—without any debate whatever, although there were two reports; and it is safe to say that most of those who voted did not know what they were voting for. It should be noted here that long before the platform came to be voted upon formal protest was made upon the floor of the convention against the convention doing any further business, as the convention was neither physically nor mentally able to combine its deliberations. Let us hope that this platform will be voted down by the membership and that proper measures will be taken for the drafting of a permanent declaration of principles by a committee appointed by the National Committee or National Executive Committee which will do its work at leisure between conventions, publishing all drafts and proposed drafts in the press, so as to give the membership a chance to consider and discuss them fully. The last thing done by the convention brought its labors back to the question of war, which was its special business. The Committee on War and Militarism had decided that the convention should issue an address to the Socialists of the belligerent countries. The work of drafting this address was turned over to a sub-committee consisting of Berger, Hogan, Sadler and Boudin. Berger prepared an address which was in keeping with the “majority report” and Boudin prepared an address which was in keeping with his own minority report. But after the two draft addresses had been prepared Berger announced that he would withdraw his draft, as he wanted to avoid another fight in the convention. So the Boudin address was adopted “unanimously.”

The Class Struggle and The Socialist Publication Society produced some of the earliest US versions of the revolutionary texts of First World War and the upheavals that followed. A project of Louis Fraina’s, the Society also published The Class Struggle. The Class Struggle is considered the first pro-Bolshevik journal in the United States and began in the aftermath of Russia’s February Revolution. A bi-monthly published between May 1917 and November 1919 in New York City by the Socialist Publication Society, its original editors were Ludwig Lore, Louis B. Boudin, and Louis C. Fraina. The Class Struggle became the primary English-language paper of the Socialist Party’s left wing and emerging Communist movement. Its last issue was published by the Communist Labor Party of America. ‘In the two years of its existence thus far, this magazine has presented the best interpretations of world events from the pens of American and Foreign Socialists. Among those who have contributed articles to its pages are: Nikolai Lenin, Leon Trotzky, Franz Mehring, Karl Liebknecht, Rosa Luxemburg, Lunacharsky, Bukharin, Hoglund, Karl Island, Friedrich Adler, and many others. The pages of this magazine will continue to print only the best and most class-conscious socialist material, and should be read by all who wish to be in contact with the living thought of the most uncompromising section of the Socialist Party.’

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/class-struggle/v1n1may-jun1917.pdf