More historic gold from Liebknecht’s letters to the Workingman’s Advocate, this time as he introduces U.S. workers to the congress at Eisenach and the program of the Social-Demockratische Arbeiter Partei, where Marxists began to differentiate from Lassalleans. As well, he delivers the news of the week.

‘Letter from Leipzig, IV’ by Wilhelm Liebknecht from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 7 No. 24. February 11, 1871.

Leipzig, January 15, 1871

To the Editor of the WORKINGMAN’S ADVOCATE:

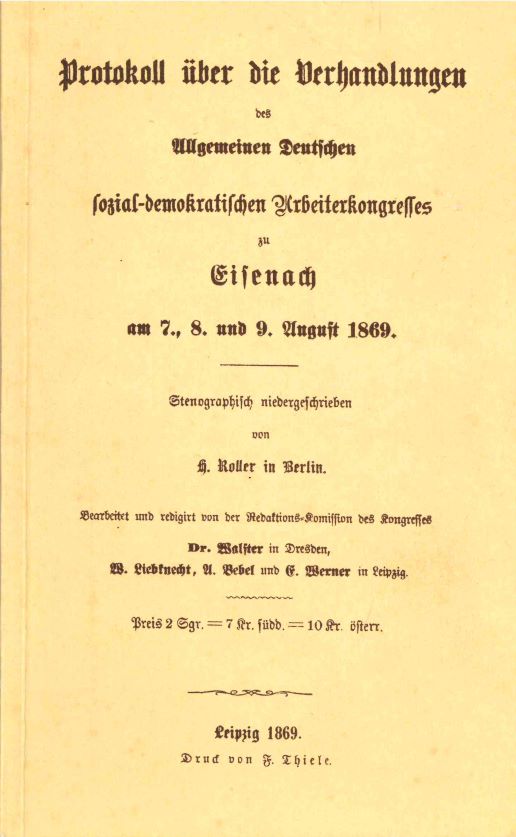

Reserving it for another time, to sketch for my American brethren a succinct history of the Socialist-Democratic movement in Germany, I will today lay before them the Eisenach Program, on which our party has taken its stand, and from which it is generally named “the party of the Eisenachers.” Eisenach, a little town situated in the heart of Thuringia, is one of the prettiest spots in this province, so rich in picturesque scenery; down on it looks the proud Wartburg, where in the twelfth century the half mythical “war of the Minnesänger” (Troubadours), known as the Sängerkrieg, took place, and where four centuries later Euther sheltered himself from the persecution of Emperor Charles the Fifth, and finished that grand monument of the German language, his translation of the Bible. Here, amidst soul-stirring and mind-elevating reminiscences of that past, there assembled in the first week of August, 1869, more than two hundred delegates, chosen by the workingmen in all parts of Germany; Prussia, Austria, Württemberg, Saxony, Bavaria, Hessen and the other divisions of our still much divided Fatherland, had sent their contingents and delegates, some from the banks of the Rhine, the Danube, the Maine, the Elbe and the Oder, from the Baltic Sea and the German ocean, from the foot of the Alps and the Lowlands of the North, represented “German unity” far better than the “North German Reichstag” did, of which half of Germany was excluded, and better too than the new “German Reichstag” will do, of which one third of Germany–German Austria is excluded. An attempt made by a body of people in the pay of the Prussian Government, to frustrate the deliberations, was speedily put down; the Congress went to work with a right good will, and agreed, after long and conscientious debates, about the following program, the principal authors of which, by the by, are now, hardly without an exception, in prison–a fact illustrative of the political condition of my native country, and warmly to be recommended to the attention of those strange republicans who are in love with our “New (Bismarckian) Era.”

PROGRAM OF THE PARTY OF SOCIALIST-DEMOCRATIC WORKINGMEN

(Programm der Social-Demockratische Arbeiter Partei)

I. The Party of Socialist-Democratic Workingmen aims at the establishment of a free commonwealth, organized by the people for the people (literally “the free state of the people,” des freien Volksstaats.)

II. Each member of the Party of Socialist-Democratic Workingmen pledges himself to act with all his energy in accordance with the following principles:

1. The present state of political and social affairs is unjust in the highest degree, and must therefore be combated with the utmost vigor.

2. The struggle for the emancipation of the working classes is not a struggle for class privileges and exceptional advantages, but for equal rights and equal duties, and for the abolition of all class government.

3. The economical dependence of the workingmen upon the capitalists constituting the base of serfdom in every shape, the Party of Socialist-Democratic Workingmen aims at the abolition of the present system of production (the wages system) and will by the introduction of cooperative labor secure to every workingman the full fruit of his labor.

4. Political liberty being indispensable for the economical emancipation of the working classes, the social question cannot be separated from the political question; it cannot be solved without this, and it can only be solved in a democratic commonwealth.

5. Considering that the political and economical emancipation of the working classes is not to be achieved unless by their combined and concentrated efforts, the party of Socialist-Democratic Workingmen creates for itself a centralistic organization, which however leaves every single member free to exercise his influence in favor of the whole.

6. Considering that the emancipation of labor is neither a local nor a national, but a social task common to all countries in which modern society exists, the Party of Socialist-Democratic Workingmen considers itself, as far as the laws concerning the right of meeting allows it, as a “Branch of the International Workingmen’s Association,” and adheres to its program.

III. The points to which at present the agitation of the Party of the Socialistic-Democratic Workingmen is chiefly to be directed, are the following:

1. Universal, equal, direct and secret suffrage (ballot) to all males from the 20th year for the elections of the German Parliament, for the Diets of the single States, for the provincial, communal and all other representative bodies. The elected deputies are to receive sufficient payment.

2. Introduction of direct legislation through the people. The people are to have the right of proposing and of rejecting laws.

3. Abolition of all privileges of rank, property, birth and religion.

4. Establishment of a Militia (after the Swiss system) in place of the Standing Army.

5. Separation of the Church from the State, and of the School from the Church.

6. Obligatory instruction in the public schools (schools for the people, Volkschulen) and gratuitous instruction in all public establishments for education (universities, colleges, academies, etc.)

7. Independence of judges and tribunals: introduction of trial by juries, and of courts of arbitration in matters of trade and commerce; introduction of public and oral pleading before the courts of justice; gratuitous justice.

8. Abolition of all laws concerning the press, the right of meeting and the right of combination; introduction of the “normal work day” (a law fixing the hours of daily work); restriction and regulation of the work of women, prohibition of the work of children; removal of the competition created by the work in prisons to the labor of free workingmen.

9. Abolition of all indirect taxation, and introduction of one direct progressive income tax and inheritance duty.

10. Public measures to promote the system of association, and opening of a public credit for cooperative societies, established on democratic principles.

Before proceeding I have to make a few explanatory remarks about this program, which contains much that must appear hardly intelligible to the citizens of a free commonwealth, but which, if closely looked at, gives a better insight into the political state of Germany than a whole volume filled with descriptions and reflections would. That we are obliged to enumerate amongst the reforms to be striven for such demands as abolition of the privileges of rank and birth, separation of State and Church, independence of tribunals and introduction of trial by jury, abolition of laws gagging the press and the right of meeting and combination, etc.; will show you how backward we, like most nations of our continent, are in matters appertaining to the A-B-C of politics; and it will teach those a lesson who, on account of the social inharmonies. existing in the United States not less than in the monarchies of Europe, are inclined to underrate the importance and the blessings of the political liberty you enjoy. How much bloodshed, what an amount of misery would have been, and would still be spared to us, if we had free institutions like yours. Liberty does indeed not work miracles, and cannot, of itself, change abject poverty into honest independence, but like the air we breathe, it is necessary for our existence; if it is denied us, our growth and development must become sickly, and only when we are able to draw it in with the full force of our lungs, the body politic can feel quite healthy, and the single member of the State acquires strength and power to help himself. If he does not use this power, it is his own fault; certain it is, that the citizens of a free commonwealth are the masters of their destiny, or, as we Germans say, the smiths of their fortune, while the inhabitants of an unfree country are trammeled in all their movements, and prevented from helping themselves. Therefore have we, what would be senseless in the United States, put the demand for a free commonwealth at the head of our program, well convinced that the struggles for a radical improvement of modern society, in other words, for the emancipation of labor must remain hopeless as long as the victims of social inequality and injustice are deprived of political liberty.

About the points under article 2 I need not speak, they being in strict, almost in literal accordance with the program of the International Workingmen’s Association, which is surely known to all my readers.

Of the points under article 3, only the two first and the eighth require a short commentary. It may seem strange that we, who are in possession of “universal suffrage,” still call for that fundamental right. The fact is, we have universal suffrage for the election of no other representative body but the North German (now called German) Reichstag–the Landtage (Diets Chamber) of the different single States, which have even more important duties than the powerless Reichstag, are elected after laws directly or indirectly excluding the great majority of the people. Besides the “universal suffrage” for the Reichstag is, as I think I told you before, restricted materially by the exclusion of all male citizens between the 20th and 25th year, and furthermore crippled by a clause forbidding the payment of the deputies–a clause framed avowedly for the purpose of rendering it impossible for workingmen to send a representative not belonging to the moneyed classes, or themselves to accept a mandate. If this object has been partly thwarted the merit is due to the truly spirit of the German workingmen, who shrink back from no sacrifice.

“Direct legislation, through the people” is a theme which before the present war occupied large political circles; it was discussed in almost every democratic paper, and in Switzerland (in the Canton of Zürich, for instance) the attempt has, with best success, been made to carry the theory into practice. The demand for direct legislation is grounded on the undoubtedly right supposition that the sovereignty of the people amounts to more than merely the right of electing representatives; that it is a right not to be transferred, and that if for practical reasons, the representative system must be resorted to, the sovereign power yet continues to rest in the people and interruptedly has to be exercised by it, independently of the functions of the representatives elected in the shape of a regular and direct participation in the legislation. And not only must it be the duty of the chosen legislators (respecting the executive body) to submit all important laws framed by them to the sanction of the people, but the people must also have the right to propose laws on their own initiative, of course in reasonable limits, guarding against frivolous abuse. Unless the people exercise their sovereign power in this manner, there is always–even in a democratically constituted commonwealth, as the example of Switzerland has shown–some danger that the representative bodies, instead of being the servants of the people, become its masters, and establish a kind of despotism, perhaps not so galling as the despotism of brutal force, but still fraught with great evils, and not worthy of free people.

Concerning the notice about prison labor in the eighth article of our program, I have only to mention that in most German prisons the custom prevails to let the prisoners work for contractors, and to pay to them wages far lower than those which free laborers, who have no other source of subsistence, can live. The consequence is the ruin of large bodies of workingmen. I need hardly say that we have no wish to deprive the prisoners of useful labor, which is indispensable for their moral purification; what we want is, that the produce of their labor shall not be sold below the market price. The fairness of this demand is so obvious, that a few of our smaller governments have already complied with it, while the larger ones always less inclined to listen to reason from below–yet stick to the old practice.

After having finished the program which was unanimously accepted, the congress took into consideration the question of practical organization, a very difficult matter, if we think of the German laws restricting the right of meeting–laws cunningly concocted with a view of preventing the formation of societies and clubs not agreeable to the governments. However the difficulties were overcome and a plan was devised, which in every respect has fulfilled the expectations of its originators, although it had to be carried out under the most unfavorable circumstances, and to which it is essentially due, that our party in spite of persecutions unprecedented in the German history of the last twenty. years, remain unbroken, yea unshaken. In my next letter I shall give a brief exposition, setting forth the essential details.

Count Bismarck is said to be seriously ill,’ and to be bent upon withdrawing from public life as soon as the war has been brought to a happy conclusion. If he is to wait for a happy conclusion in his sense, he may have to wait long. He finds himself in a very awkward dilemma; either he must conclude a peace with the French Republic, and then the Prussian Junkerdom, of which he is the chief, is doomed, or he must carry on the war at any cost, and this cannot be done without imposing on Germany such fearful burdens, and bringing upon her such misery, that the patience of the most patient people will at last be exhausted and a state of feeling created which must cause the speedy downfall of caste, which alone is responsible for the continuation of the war after the surrender of Sedan–that is, of the Prussian Junkerdom with Bismarck at its head.

I see Thomas Carlyle is at his trick again; he has pronounced emphatically and energetically in favor of Count Bismarck, and is reviling everyone that sympathizes with the French Republic. The “hero worship” of Carlyle is only another name for what in common language is called servile admiration of success. You will recollect that in the beginning of the late Rebellion, while the slaveholders were victorious, he declared for the slaveholders. The man whose “hero” Jefferson Davis was a few years ago, will have found it easy to transfer. his “worship” to “hero” Bismarck.

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

Access to PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-02-11/ed-1/seq-2/