A review of the 1936-7 Fantastic Art at the Museum of Modern Art by the always compelling Marxist art historian and critic Charmion von Wiegand, who places surrealism in its artistic and social context. Photos from original exhibit.

‘The Surrealists’ by Charmion Von Wiegand from Art Front. Vol. 2 No. 12. January, 1937.

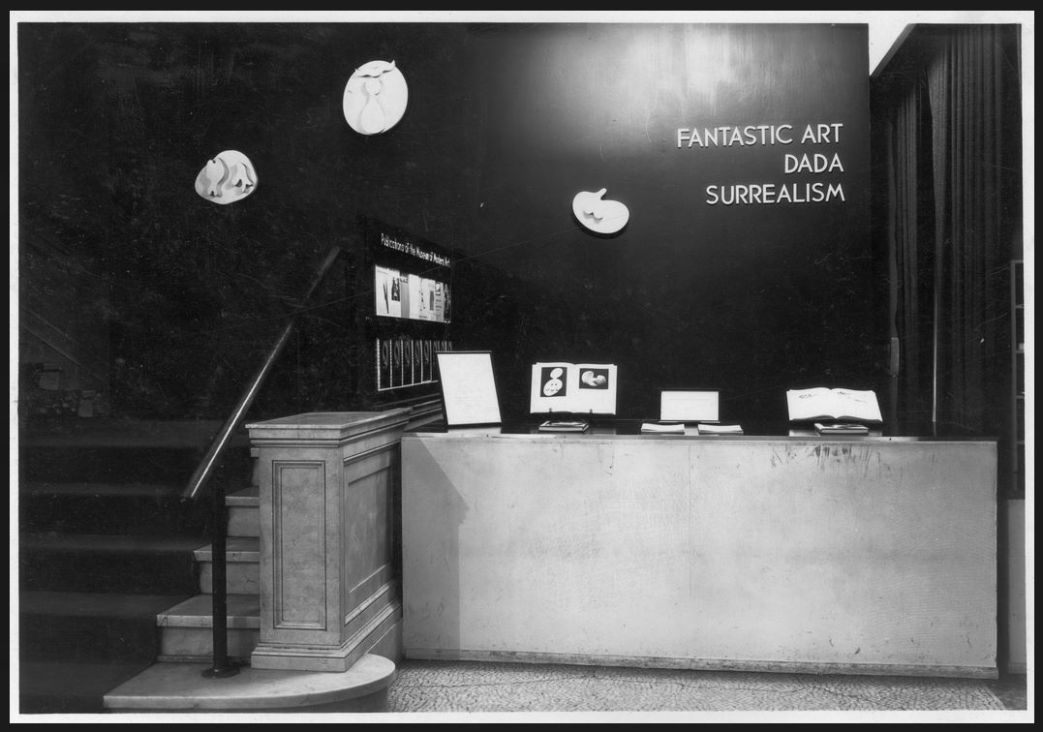

THE present exhibition now on at the Museum of Modern art called Fantastic Art, Dada, and Surrealism arouses belated echoes of the post-war controversies which rocked the European art world more than a decade ago. The shell-shocked imagination of the continental artists exposed for over four years to the unendurable reality of destruction and war, the disintegration and social chaos which grew out of the bloody slaughter, revolted and found relief in a fantastic world where the usual logical and rational concepts ceased to be valid. If the explosive anarchism of Dadaism (born in 1916) intent upon wiping out existing notions of beauty and obliterating all individuality was mad, madder still was the world it reflected where millions of human beings were perishing and the whole cultural heritage of man was overthrown in the ruthless struggle for power.

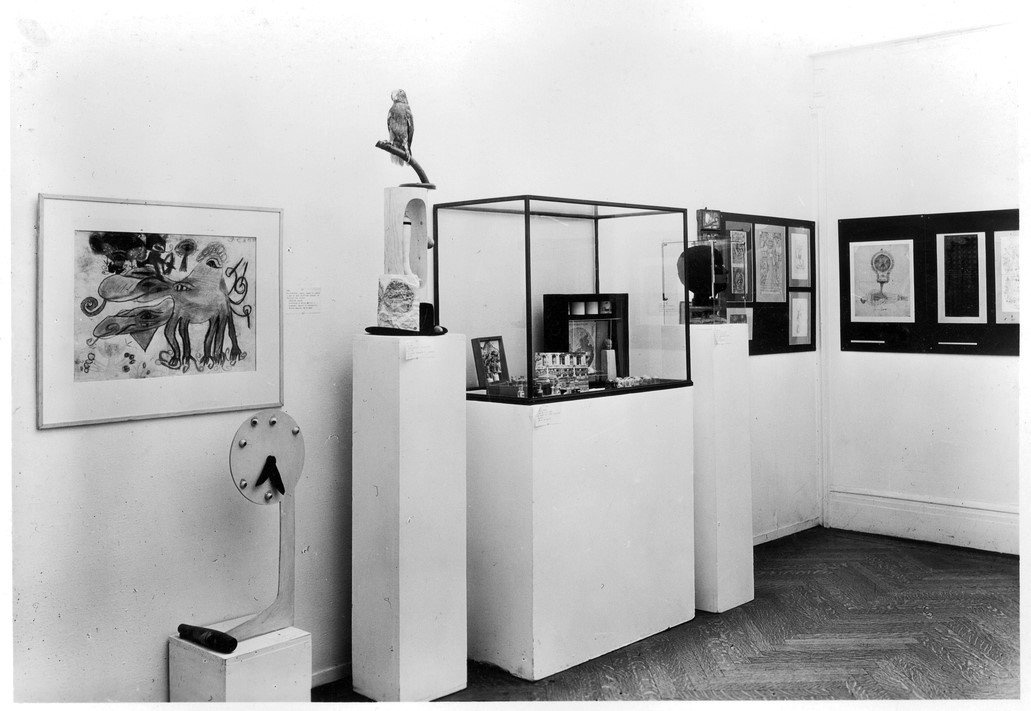

The museum has arranged its exhibition in historical sequences and if you have the sardonic humor of Dada, you may see it with the eyes of the visitor, who termed it “just four floors of good clean fun.” But if you are more seriously inclined, you may see in the astonishing potpourri of paintings, collages, sculpture and unesthetic objects in general, the heroic effort of man to adjust himself in a tragic dilemma, the need to find release from the unbearable confusion and contradictions inherent in a dying social order.

Fantastic art has always existed in all peoples and all societies. Its two great branches–grotesque and erotic art–are inevitable manifestations where human energy is not reduced to the minimum of self-preservation. Good as the present exhibition is, it is a sterilized version of fantasy, in which the extreme aberrations of the grotesque and particularly the erotic have been politely eliminated. But the addition of a section devoted to fantastic art in Europe since the end of the middle ages with examples of Bosch, Duerer, Hogarth, Blake, Goya and the belated romantics, despite many astonishing resemblances to surrealist images, only serves particularly in the early old masters to bring into sharp contrast the tremendous difference between the robust imagination of a growing society disengaging itself from medieval superstition and “the sickness of the world” which is surrealism self-styled.

It is impossible in small space even to review this enormous collection of “art” objects of all times and of varied esthetic worth from fur-covered cups, zipper-eyed suede maidens, bearded grapes, mathematical objects, rotating glass machines, bird-cages filled with sugar, collages of all sorts, architectural photographs, prints, paintings and sculpture. A serious omission is the lack of photomontage–in particular, the work of John Heartfield–the one phase of modern fantastic art which has received universal approbation and has been incorporated in our everyday existence.

Is it possible to rescue sense out of confusion and discover the meaning behind the surrealist efflorescence of fantasy in a hard-headed and rational age? The Cubists, we know, reduced the human body into separate parts, analyzing and dissecting it with surgical precision until they had destroyed its organic unity. The Surrealists seem to wish to perform the same task for the human mind. Their work coming after Cubism represents and reflects an even more acute crisis in the disintegration of the individual in capitalist society.

Three events in the beginning of this century hastened the death of the old order of society. They were the destruction of the concepts of the physical world relativity; the destruction of the moral with Einstein’s discovery of the theory of concepts of our social life by Freud’s theory of psychoanalysis; the destruction of existing political structures with the social revolution in Russia. These dying paroxysms of capitalism mirrored in the field of the arts have caused the artist to frantically seek some solution to the death-dealing contradictions in society. Painting has faithfully transmuted these crises in the social and economic world into its own esthetic and formal terms. This fact explains why a great artist like Picasso has been unable to create a single unified style in painting and has passed through the whole historical development of western art in the course of twenty years. Such a see-saw of style change is not due to individual caprice but to a deep need to rescue some synthesis from the ever-increasing confusion of our present existence.

AFTER Cubism, which destroyed the organic body, there appeared expressionism to destroy man’s environment. Nothing was left now but the human ego struggling single-handed against chaos. Dadaism took the next logical step and robbed that ego of all intellectual concepts and rational action, reducing it to a babbling, insane entity, no longer able to formulate thought, but merely to express emotion and instinct on its primary levels. With the coming of the surrealists, a crisis was reached in the orgy of destruction. Preserving the illusion of the unity of the physical universe in its old mechanical concepts of time and space, the surrealists present their lurid formulas in a dead world, cold and empty. With Dali and Ernst and Tanguy the drama of disintegration reaches the stage of active corruption–ants eating the classic features of broken statues; murmurless and melting watches; panoramas of endless sea and space in which the lines never meet; dismembered limbs and hands observing each other in unorganic relationships; and framed vistas within vistas as the infinite identical image reflected in a double mirror.

With the Italian painter Chirico, the primitive of the surrealist movement, begins for the first time the phantasmagoria of the human mind in bourgeois society–nightmares of death and destruction through dismemberment and insanity. But Chirico still preserves the vision of the past; his tragic landscapes of twilight cities sleeping by the sea and wistful mechanical muses have the haunting music of a backward-looking romantic. In the canvas, Melancholy and Mystery of a Street, painted in the fateful years, 1914, the shadows are ominous with foreboding of doom. The Sailor’s Barrack, painted the same year, offers for the first time the surrealist repertoire of unrelated objects placed against a classic background. Perhaps its hypnotic magic may be attributed to the suggestion of chaos impinging upon one familiar reality.

Picasso has also made his contribution to surrealism, but in his most fantastic creations, preserves a profound analysis of form which separates him esthetically from the official surrealists who deliberately debase painting to a chromo art or use it for the investigation of decomposing textures and academic illustration. Few surrealists proper are capable of the sensitivity of Metamorphosis or the magnificent monumental Seated Woman of 1927.

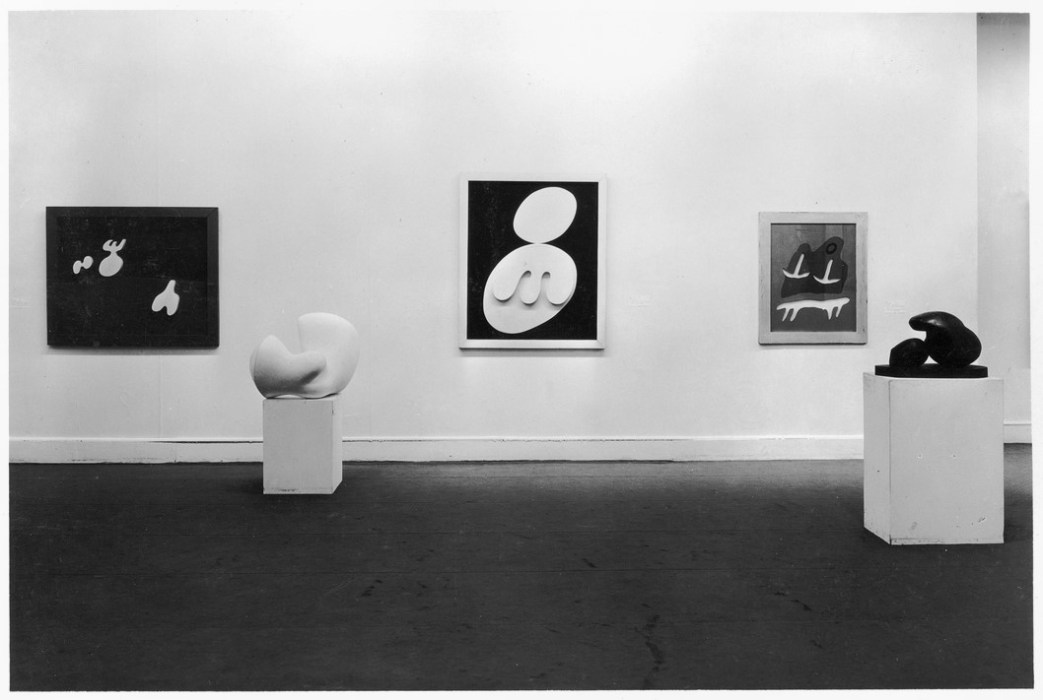

THREE exiles from the Expressionist camp have contributed vitally to the Surrealist movement and esthetically in some respects they overshadow it. They are Kandinsky with his abstract colored music; Grosz with his savage social satire; and Paul Klee with his ironic and exquisitely refined line. Certainly neither Hans Arp with his sensuous abstractions in various materials nor Miro with his lively inorganic microbes moving precisely across wide color spaces has the tremendous penetration of Klee, whose Mask of Fear compels attention by its primitive magic force united with the utmost civilized sophistication.

There is no space here to discuss the contribution of Marcel Duchamp, Picabia, Man Ray and other outstanding exponents of Surrealism. In many respects, the work of Max Ernst is the most important, his relation to Surrealism is on a par with Picaso’s relation to Cubism. Coming out of Dadaism, Ernst incorporates in the body of his work all phases of surrealist development. Prolific in invention, he has a special ingenuity in the discovery of texture, particularly the textures of decomposition. In him one finds disconcerting and confusing contrasts ranging from debilitating chromo illustrations to plastic conceptions equal to Picasso. In this respect, Ernst probably most correctly mirrors the contradictions in the external world. His vision assumes an apocalyptic aspect in which objects no longer obey even the laws of dead time or space but move automatically in unreal relationships as occurs in the subjective drama of the unconscious or in our dream life.

Salvador Dali, the Catalan painter, now in the United States, has received the most public réclame for his paintings, but actually has added little to surrealist invention aside from the theory of the precise materialization of delirious images of concrete irrationality. He has dramatized in correct, academic perspective–the more concretely to realize horror–the obsessions and neuroses of society today–the sadism, the destructive egotism, the sexual perversions, the infantile regressions, the remnants of primitive magism, atavistic fossils from humanity’s historic dawn.

Dali’s painting pursues the same logical course of regression common to insanity in the human individual. His writings on the paranoic obsessions are remarkably acute observations of logical deduction. Just as the logical structure of the mind often remains intact in the insane individual, providing him with a shrewd cold calculation alternating with fits of emotional instability and rage, so Dali displays acute intellectuality in the face of the most violent emotional aberrations. His work mirrors the festering sores of society, the murderous sadism, the pompous bombast, the cold violence which finds its physical outlets today in the methods of Fascist persecution and violence. A scientist of corruption, Dali deals in the “three great images of life–excrement, blood and putrefaction” and from them creates his pornographic postcards for an effete intelligentsia. With the introduction of photography in the 19th century, art and eroticism hitherto always united, went their separate ways. Cubism with its destruction of the body eliminated sex. Dali has reunited art and eroticism by a discovery which the photograph has not been able as yet to make use of the pictorialization of Freudian symbolism. The contradiction between Dali’s reactionary technique of miniature painting and his advanced psychology reveals the fundamental and ever-growing schism in society due to the vast discrepancy between its ideals and its behavior.

DALI declares that the purpose of his art is “to systemize confusion thanks to a paranoic and active process of thought and so assist in discrediting completely the world of reality.” So far the artist may travel on the road to destruction but in the end he is faced with annihilation of art and life itself.

It is no accident that the Surrealists have surrendered to the revolution and proclaimed their allegiance to it–albeit in their own anarchist fashion. Intellectually, they make the step across the great divide between the death of an old culture and the birth of a new one. But emotionally they are enchanted with the art of corruption and with the swift rhythm of disintegration in a dead universe. Just as the allegiance to the old classic gods lived on for centuries under Christendom in the witch heresies, the black mass, the devil and the Walpurgis night, so the Christian myth from a time when religion was a progressive social force, now grown old and evil and corrupt, lives on in the Surrealists’ devotion to the “marvelous” and “the blind and often ugly grandeur of miracles.” In their “frantic and pathetic search for Evil” they reveal all the reactionary tendencies of belated romantics.

But not all of Surrealism is merely decadent, not all of it corrupt with the festering sores of dying individualism faced with a future collective world. From its evil-smelling, putrefying fertilizer, new shoots of life may spring. Impressionism enriched our life with new color values, Cubism with new plastic innovations and Surrealism is contributing new discoveries of the inner life of fantasy by pictorializing the destructive and creative processes of the subconscious mind. The art of the future, which will strive for a new humanism on a social basis will inevitably turn its face toward the world of reality again. In doing this, it will find uses for the technical inventions of the modern escapists, whether Cubist or Surrealist, just as Soviet society today is turning the scientific inventions of the bourgeois world to new collective uses for the benefit of every individual.

Art Front was published by the Artists Union in New York between November 1934 and December 1937. Its roots were with the Artists Committee of Action formed to defend Diego Rivera’s Man at the Crossroads mural soon to be destroyed by Nelson Rockefeller. Herman Baron, director of the American Contemporary Art gallery, was managing editor in collaboration with the Artists Union in a project largely politically aligned with the Communist Party USA.. An editorial committee of sixteen with eight from each group serving. Those from the Artists Committee of Action were Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Zoltan Hecht, Lionel S. Reiss, Hilda Abel, Harold Baumbach, Abraham Harriton, Rosa Pringle and Jennings Tofel, while those from the Artists Union were Boris Gorelick, Katherine Gridley, Ethel Olenikov, Robert Jonas, Kruckman, Michael Loew, C. Mactarian and Max Spivak.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/parties/cpusa/art-front/v2n12-jan-1937-Art-Front.pdf