A.B. Magil review the Artef (Jewish Workers’ Theatre) production of ‘Hirsch Leckert’ about the avenging Jewish socialist martyr, executed for the attempted assassination of the pogromist governor of Vilnius in 1902.

‘Hirsch Leckert at the Artef’ by A.B. Magil from New Masses. Vol. 7 No. 12. June, 1932.

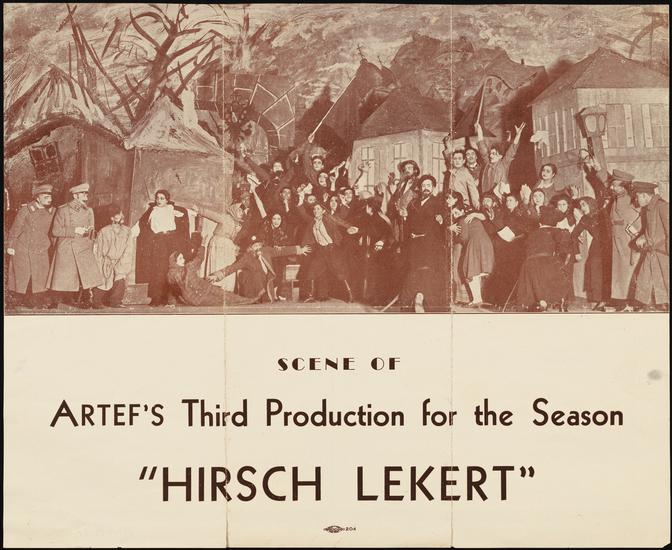

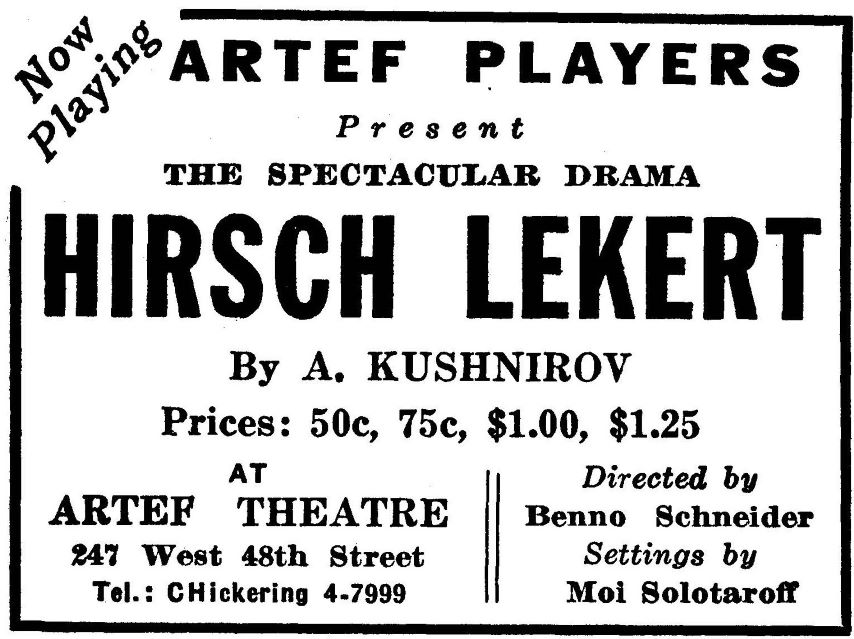

Hirsch Leckert, Historical-Revolutionary Drama by A. Kushnirow. Produced by the Artef (Jewish Workers’ Theatre). Directed by Beno Schneider. Settings and Costumes by M. Solotaroff.

Strong and moving, with play, actors and sets fusing to form a single organic whole, the new Artef production, Hirsch Leckert, marks a great leap forward along the path of the creation of a vital proletarian drama in this country. No need for apologies here. No need for reservations or those omnipresent “extenuating circumstances.” Here is a finished performance, a creative achievement that bites into the imagination and whips the emotions into play. And the Jewish workers who flocked to see Hirsch Leckert showed how much a part of their own struggles this story of czarist Russia of thirty years ago is.

From Trikenish (Drought), the last Artef production, to Hirsch Leckert is a journey to another wold. Trikenish, the Yiddish version of Can You Hear Their Voices?, as produced by the Artef, never took on the flesh of life. The Artef players declaimed Trikenish, they didn’t act it; and bad direction didn’t help them any. But Hirsch Leckert, besides being a better play, offered material that was obviously closer to them, if not in time and space, at least in spirit. It may be too bad that when Jewish worker-actors try to interpret American farmers, they produce either clowns or tragic Second Avenue heroes, while, on the other hand, they can make Jewish workers of thirty years ago seem very much alive, but if Trikenish and Hirsch Leckert are any criterion, it happens to be the truth. Hirsch Leckert really lives. and moves; intelligently directed and stirringly acted, there are no creaking joints.

It is now nearly thirty years since the Jewish cobbler, Hirsch Leckert, fired the shot at Von Vaal, governor of Vilna, that was meant to avenge the bloody suppression of the May Day demonstration by the czarist satrap. It is nearly thirty years—yet today the name of Leckert, who died on the gallows, is for thousands of Jewish workers throughout the world an unwithered symbol of heroic struggle and sacrifice. And in the city of Minsk, U.S.S.R., the Workers’ Republic has built a monument to the simple cobbler who was one of the trail-blazers of the proletarian revolution.

No writer could want more vital material than the period of Leckert’s martyrdom, the period immediately preceding the 1905 revolution. The well-known Soviet Yiddish poet, novelist and playwright, A. Kushnirow, has used if not all (which would have. been impossible), yet an important section of this material, and used it well. He shows us Jewish workers, real proletarian types, shows them in struggle against the czarist regime and in conflict with their own leaders, the timid intellectuals of the Bund. He shows us in the person of Sonia Schereschevsky the deluded worker, who unwittingly becomes a “Zubatofka,” a police agent, but at the end realizes her mistake. On the other side, he shows us the brutality and corruption of the czarist officials and the treacherous role of the Jewish capitalists and rabbis. And the play is not an abstract thesis; its figures are human and its ideas are expressed through the development of the living class struggle. Leckert, too, is not romanticized, but is presented as he was, a rank and filer, one of the mass, who came forward at a particular historic moment as the embodiment of the desperation and fiery heroism of the masses. But the play falls down ideologically at a most important point: it fails to contain any criticism of the attempt at assassination. The act of Leckert, viewed in historical perspective, was a heroic act of class vengeance and at the same time a protest against the legalistic opportunism and timidity of the leaders of the Bund. Nevertheless, as an act of individual terror, it tended to lead the workers away from the path of organized struggle, struggle not against individuals, but against the system of capitalism and semi-feudal parasitism. Failure to point this out means failure to perform the supreme task of proletarian art: to be that dialectic synthesis which not merely presents pictures of the class struggle and indictments of bourgeois society, but shows, either explicitly or implicitly, the path that must be followed for the transformation of that society into its direct opposite, the dictatorship of the proletariat.

Yet despite this major shortcoming, Hirsch Leckert remains a significant proletarian play. And what minor defects there are in the presentation (such as the over-caricaturing of some of the czarist officials) are swallowed up in the excellence and vitality of the production as a whole. Hirsch Leckert is the finest achievement not only of the Artef, but probably of the American proletarian theatre in any language.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1932/v07n12-jun-1932-New-Masses.pdf