Thousands of students strike against the expulsion of the editor of the student paper for his writings on the Kentucky miners’ struggle, and are attacked by police and the football team at New York’s Columbia University in 1932. The full story below.

‘Columbia University Strikes’ from Student Review (N.S.L.). Vol. 1 No. 4. May, 1932.

WHEN Reed Harris became editor of Spectator, there was little reason to regard his election as an occasion for rejoicing. For so many years, Spectator had confined its attention to campaigns for a new fence around South Field or for bigger and better support for the football team, that no one had any intimation that the new Spectator staff was to show a serious concern for serious matters.

In November the newspaper attracted attention with an attack on commercialism in football. There was much buzzing around about forcing Spectator to prove its charges. and Captain Ralph Hewitt of the football team threatened to sock Harris in the eye. Harris offered to substantiate his charge if the Athletic Association would open its books for his perusal. “The demand for proof was thereupon allowed to languish. From the controversy Spectator drew this very sage lesson, that colleges should have not a small group of pampered stars and high-priced coaches, but a system of intra-mural sports which would involve the majority of students.

From the football battle the new Spectator went forward to other battles. While Clarence Lovejoy, secretary of the alumni association, and other prominent and generous alumni, cried out for Harris’s scalp, the new editorial proceeded to cast aspersions on sanctified institutions and to behave in such a sensible manner that one prominent alumnus complained that they were too “grown-up.”

In the ensuing months, Spectator attacked R.O.T.C. and urged the removal of military units from the campus of C.C.N.Y. and other colleges. Spectator urged freedom for Tom Mooney and unemployment insurance for workers. The basis on which student jobs are awarded by the appointments office was attacked, as was the censorship of Hunter College Bulletin. Anti-semitism, an issue which is very much alive at Columbia, and which is usually carefully avoided by Spectator editors, was considered, discussed and attacked. The national and local leadership of the Republican party was scathingly denounced, and President Nicholas Murray Butler received, as a result, letters from his fellow Republicans. National politics, irrespective of party, came in for the same treatment. ‘The sacrosanct senior society, the Nacoms, of which Harris had been a member, was attacked, much to the distaste of those alumni who took seriously the mystic mumbo-jumbo of the secret organization. Although several persons high in administrative circles of the college heartily disapproved the student trip to Kentucky, Spectator supported the expedition with some enthusiasm and plenty of space. (The Alumni Bulletin, on the other hand, expressed intense opposition.) Finally, Spectator reopened an old sore in demanding an investigation of the John Jay Dining Rooms. Charges had been made that prices were too high and that student waiters were mistreated and underpaid. It had been suggested as far back as the year before that the student dining rooms, ostensibly operated for the service of the students, were actually operated for personal profit.

In almost all of these matters there was plenty of publicity. Although one would hardly call President Butler a shrinking violet, he is said to resent publicity, any publicity, that is, which does not rebound to the credit of the institution he directs. Judging from the “letters to the editor” columns in the downtown press, it is not hard to guess that President Butler and the administration received considerable mail, on their own, from protesting alumni and donors.

From some quarters of the student body and the faculty, there came the criticism that Harris and Spectator (and the Columbia students who figured in the Kentucky expedition) had been “‘tactless’ in drawing Columbia into such undignified prominence. Those who made these complaints loudly protested their impartiality and insisted that objections were based purely on the manner in which Harris made his charges. It is significant, however, that the complainants were persons who either disagree fundamentally with the positions which Harris took or who stand very close to the administration.

The day after the dining rooms case was reopened, Harris was called before Dean Hawkes and informed that his “registration had been cancelled.” Harris was taken before the committee on instruction, sitting at that time, for reasons which no one has been quite able to understand, inasmuch as every one, including the Dean, stated that the committee had no powers to veto or modify his expulsion order. This fact gives considerable credence to Harris’s statement, since denied by the Dean, that the Dean remarked that there must be “the appearance of a hearing.” “I talked with President Butler today,” the Dean is quoted as saying, ‘”and he agreed with me that Mr. Harris’s registration should be cancelled.”

A statement was issued almost simultaneously from the office of the Dean which said: ‘Material published in Spectator during the last few days is a climax to a long series of discourtesies, innuendoes and misrepresentations which have appeared in the paper during the current academic year and calls for disciplinary action.” President Butler replied to all inquiries that he had no knowledge of the expulsion.

Student resentment ran high when school reconvened on the following Monday, and the announcement of a mass meeting, called by Social Problems Club on the library steps drew about 4,000 students. When Arthur Goldschmidt of the Social Problems Club asked for a strike vote, the response was overwhelming and plans were laid for a student strike on the following Wednesday. On Tuesday when a second mass meeting was called, an opposition which can be characterized with accuracy as fascist put in its appearance. It was confined to “the football crowd’? who engaged in throwing eggs at the student speakers. The students called on the egg throwers to put their arguments in words, and under the challenge of “yellow,” one football man took the platform and said “I think it’s a lot of boloney.” Another, more articulate, declared “We all know what Harris said is true. But he didn’t have to say it in public.” At the yells and boos of the students, he fled in confusion.

A student strike committee, representative of the student body but under the leadership of the Social Problems Club and the National Student League, immediately issued a strike call, which was printed and put into the hands of the students. The call reviewed briefly the militant editorial policy of Harris, pointed out that Harris had supported student rights and had taken the working class point of view on many current economic issues. It put forward as demands the reinstatement of Harris, a student-faculty investigation of the John Jay Dining Rooms, and a similar investigation of the college athletics. “The school strike is a positive step towards insuring that the student newspaper shall be a student newspaper,” said the strike call. “It is a demonstration of student interest in student affairs. It means the furtherance of the issues for which Harris has fought and for which every student is now urged to show his support.”

This was obviously a free speech fight, but the Social Problems Club was attempting to get to the deeper political significance of the issue. It was not only the right of free speech, but the right to defend student rights and to campaign for their interests that was at stake. It was because Harris had done this that he was denied the right of free speech.

In the meantime, the position of the administration was changing. A delegation of conservative students. had been informed by the Dean that Harris was expelled for “personal misconduct.” (The phrase was more recently trotted out when the editor of the University of Wyoming paper was expelled.) Student delegations sent by the strikers were a little later informed, both by Dean Hawkes and President Nicholas Murray Butler, that the reason Harris was expelled was because of an allegedly “libelous” paragraph which appeared in Spectator anent the conduct of the John Jay Dining Rooms. The paragraph ran as follows:

“Waiters asserted that the personnel in charge of the dining room evidently were working only for profit, serving poor food, attracting organizations not strictly student in character, and otherwise changing the character of the organization from one of student service to one of personal profit!”

The students were not deceived by this change of front. ‘They pointed out that the expulsion was based on the character of Harris’s editorial policy, as originally admitted by the Dean. The “libelous charges” which had now been brought into the picture had originally been printed in Spectator of the year before under the direction of the former editor, against whom no action had been taken. Neither the Dean nor President Butler were willing to explain why this paragraph might cause the expulsion of Harris while it was apparently harmless in the case of the previous editor, Finally the student committee declared:

“The question of the truth or falsity of the charges affecting the John Jay Dining Rooms is not involved. The right of an editor of a newspaper, in acting on information which he considers reliable, to make charges and demand an investigation in a matter of public interest, is a fundamental aspect of the right of free speech and free press.”

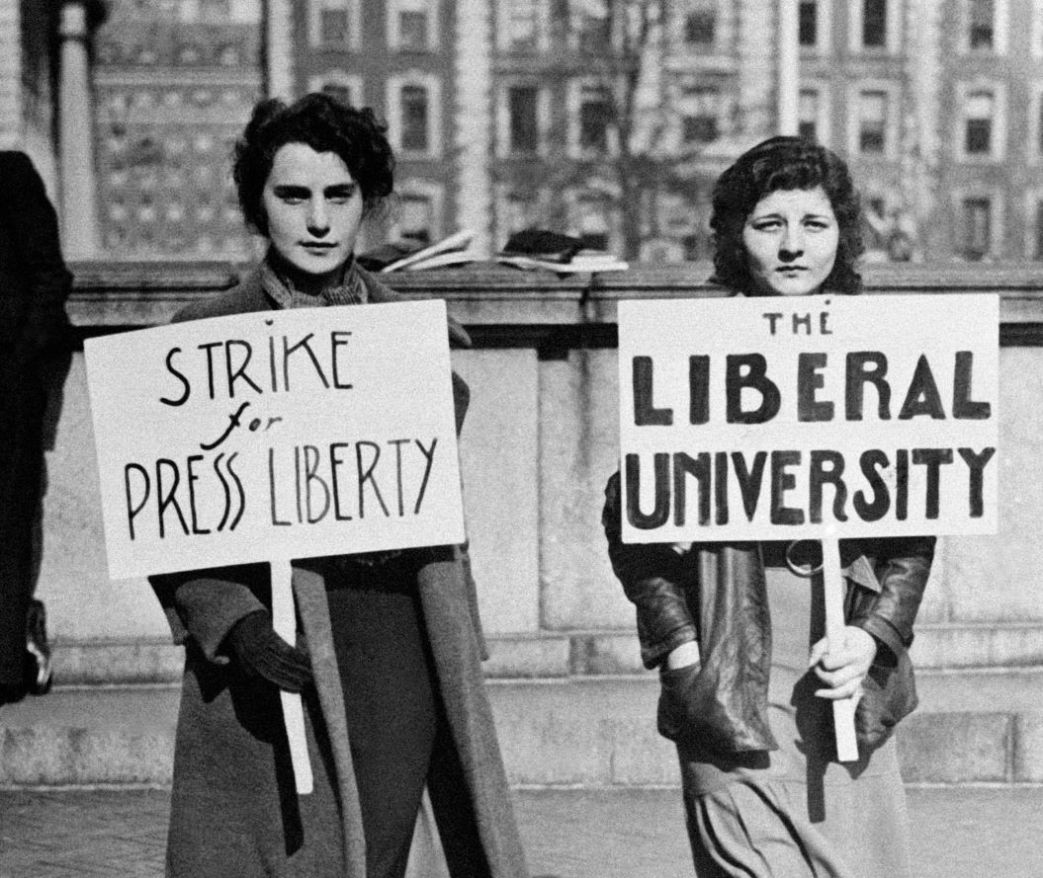

The strike was conceded to be a success. In the college, where there are 2,000 students, it was estimated that 1,500 were on strike, reinforced by approximately 2,000 in the other schools of the University. Tags inscribed “On Strike”’ were worn by the strikers, and pickets carried appropriate placards. A continuous mass meeting was held on the steps of the library, with Columbia speakers alternating with students from other colleges in the city who had been invited to participate.

While a part of the opposition group continued to throw eggs and heckle, precipitating several minor fist-fights, a wiser section of the opposition organized the Spartan Club and called a rival meeting to endorse the action of the Dean. Their appeal was primarily an appeal to loyalty towards the Dean, their attack an attack against “Communism.” They insisted, along with some of the right wing strikers, that this was purely a Columbia fight and criticized the strikers for allowing students from other colleges to participate.

Their rationalization was characteristically fascist. One of them later told this writer that he supported the Dean because he believed in discipline. “The only way to run a corporation or a university or a government is to have discipline and authority invested in one person,” he said. He was, like most of his fellow supporters of the administration, an athlete, living at the Manor House and otherwise enjoying the fruits of an athletic career. Like his fellow athletes, he had a vested interest in the administration.

The Social Problems Club had no apologies to make for inviting the cooperation of sympathetic students from other colleges in the city. The club, already affiliated with these students through the National Student League, knew the value of intercollegiate undertakings. By acting in concert with the students from other campuses, they were helping to break down that narrow and snobbish campus-chauvinism, so analogous to nationalism, which hinders students from perceiving their common objectives.

It was obvious to the club that this was not purely a Columbia fight. The year before, students had been disciplined at C.C.N.Y. for opposing R.O.T.C. A few months earlier there had been the row which was occasioned by the censorship of the student “Bulletin” by the administration of Hunter College. In the high schools of the city a most rigorous campaign of suppression was going on—it still goes on—during which Social Problems Clubs had been disbanded, student leaflets seized, and several times students had been arrested for distributing to their fellow students leaflets demanding lower lunch room prices or leaflets on similar issues.

Since the depression had become so much more severe, educational administrators along with other agents of authority, had begun to bear down all the harder on student protest movements. The club recognized that the students of Columbia had a mutual interest with other students in fighting back at such suppression. Their task was to demonstrate this to their fellow-students at Columbia and the invitation to the other colleges in the city was expected to help achieve this end. In the meantime, the Social Problems Club and the National Student League utilized their organizational affiliations and informed all member clubs of the facts of the case. Immediately, the case took on national significance and telegrams and letters of protest assailed President Butler and Dean Hawkes in great quantities.

Toward the close of the strike day, the announcement came that sixteen members of the faculty had signed a petition, directed to Dean Hawkes, urging the reinstatement of Reed Harris. Only one member of the faculty, Donald Henderson, instructor in economics, had openly allied himself with the strike movement. And while the fifteen new friends were hailed by the students, there was considerable disappointment among the student ranks. “They were fighting, they felt, for principles which their professors and instructors had constantly held up before them as valid ideals. The faculty had professed liberalism. And here in a. concrete situation in which liberal aims were involved, the liberal professors as well as the conservative ones were found wanting. “I know nothing about the case,” John Dewey told two students who asked for his signature on the petition. No one will ever know how many students went home sadly disillusioned when they heard that Dr. Dewey had refused to sign. The very fact that certain members of the faculty known to be sympathetic to the student protest, had not dared to join them openly, was a significant comment on free speech at Columbia.

That evening at a meeting of the Columbia chapter of Phi Beta Kappa, a vote of censure against the administration of the college was moved, and failed of passage by 36 to 41. The balloting, by demand, was secret. The Dean sailed two days later for Oxford, England.

By Monday of the following week, the administration had granted the second demand of the student strike. There was to be a student-faculty board to investigate the John Jay Dining Rooms. The committee as appointed by the administration included three members of the faculty, the new editor of Spectator, a member of the Spartan (pro-administration) society, and the president of the Social Problems Club. The investigating committee had been at work less than two weeks before the major demand of the strikers was granted. Harris was reinstated.

Emerging from the 1931 free speech struggle at City College of New York, the National Student League was founded in early 1932 during a rising student movement by Communist Party activists. The N.S.L. organized from High School on and would be the main C.P.-led student organization through the early 1930s. Publishing ‘Student Review’, the League grew to thousands of members and had a focus on anti-imperialism/anti-militarism, student welfare, workers’ organizing, and free speech. Eventually with the Popular Front the N.S.L. would merge with its main competitor, the Socialist Party’s Student League for Industrial Democracy in 1935 to form the American Student Union.

PDF of original issue: https://archive.org/download/student-review_1932-05_1_4/student-review_1932-05_1_4.pdf