Bertha Mailly travels to the seat of war during the 1903-4 Western Federation of miners strike in Colorado.

‘The Coal Miners’ Strike in Colorado’ by Bertha Howell Mailly from The Comrade. Vol. 3 No. 6. March. 1904.

THE foothills of the Rocky Mountains, extending from Colorado Springs down into New Mexico, guard in their bosoms unlimited treasures of bituminous coal. Lying in the hollows of the hills and wedged in their bleak canyons are the mining camps composed of wretched huts, tipples, furnaces, the company stores and saloons, that all belong to the Rocky Mountain Coal and Iron Company, the Victor Fuel Company and other corporations that control the district, its wealth of natural resources, its machines and its inhabitants.

The miners of this desolate region, to the number of ten thousand, are now on strike. They have never before made any organized resistance to the authority exercised by the coal companies, and this strike is only the culmination of several years of incessant, patient endeavor on the part of the United Mine Workers’ organizers. And this final result has been largely achieved by “Mother” Jones, who worked at the risk of her health and life to rouse the spirit of revolt to the striking point. Many of the strikers are living in tents, and all are receiving support from the national organization of United Mine Workers. They have been evicted from the company houses, and many from houses which they owned themselves, but which were upon company land.

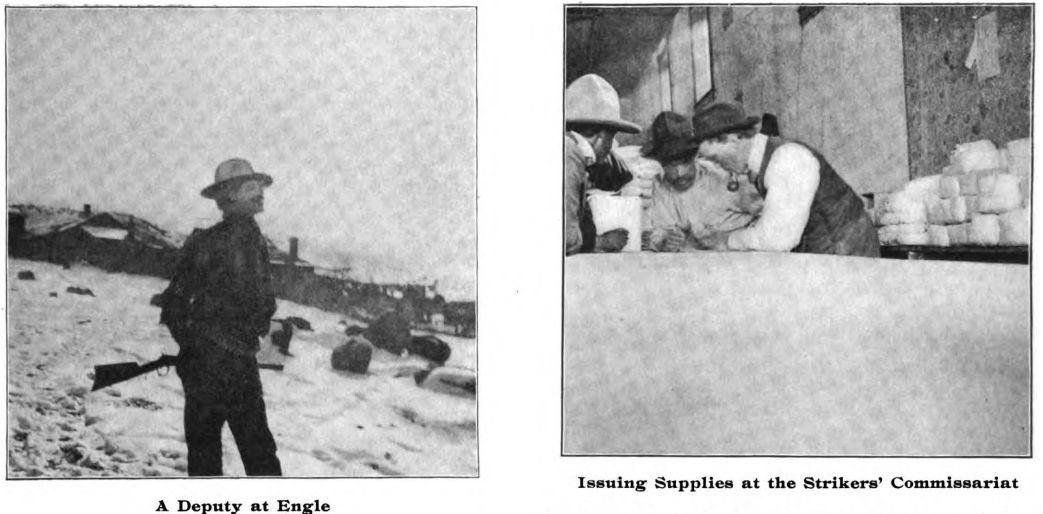

Photographs by the Author The miners’ demands are similar to those made in previous struggles in other mining centres of the country. An eight-hour day (enacted into a State law by popular referendum, but declared unconstitutional by the courts), semi-monthly pay, 20 per cent. increase in wages, abolition of the scrip system (which involves compulsory trade in company stores), payment for ton of 2,000 pounds instead of 2,500 as heretofore, and proper ventilation and safeguards against accidents. Many of these grievances have been adjusted in other mining states, so that the Colorado coal miners are only attempting to catch up with their brethren elsewhere. I shall not go into detail upon these questions in this article, but only relate incidents concerning the strike which will serve to show the true conditions obtaining throughout the district.

A dance occurred at one of the mining camps a few nights before the strike was called. Agitation and organization had been going on very quietly but surely and “strike” was in the air, although the superintendent had been heard to say: “It doesn’t matter if the whole region goes out, my mine will open up with a full force, not a man will quit.” This mine, employing five hundred men, by the way, has been absolutely closed down since the first morning of the strike. At the party this superintendent asked a pretty Italian woman to dance with him. “What!” she replied, “you want to dance with me? No, it wont do. Your ideas and my ideas don’t match. You’d lose your job in a few days if you danced with me, because I’m a miner’s wife, and you can’t be friends with us.”

The majority of the miners in this region are Italians and Mexicans, many of them not understanding English. All the country knows “Mother” Jones. When she came among them she seemed to be an “Angel” sent to right their wrongs, and they called her “La Bianca Madre” (The White Mother). In the course of her organizing she reached one camp in the forenoon, two days before the strike was called. She found that the men had been prevented from leaving camp to attend the meeting, and so prepared to drive to another place, saying that she would return at four o’clock in the afternoon. Just then a carriage approached, the driver of which said that it had been sent by the company, which would like to show her and her escort around the camp and the works.

“On one condition,” replied Mother Jones, who is accustomed to invitations from capitalists and knows how much they mean. “If you will afterwards let me address a meeting of all the men. Any representative of the company may be present, but you must let me have all the men.”

It is scarcely necessary to say that the carriage drove back to camp empty.

In the afternoon Mother Jones returned. Five hundred men had somehow gathered for the meeting. Far down the dusty alkali road they saw the buggy and ran to meet it. They grasped Mother Jones’ hands, they kissed her dress, many with tears streaming down their faces. And as they gathered on the windy hillside and listened to the recital of their wrongs, although they understood her not, they cried like children. This camp, although one of the most enslaved, was organized, and has since been one of the most loyal. Nearly all of the mining camps are guarded by armed deputies, who are brutalized products of the competitive system and whose violence, when let loose, knows no limit. I saw one of the striking miners brought into the hospital at Trinidad beaten and bloody. With a companion he had gone to a camp some three miles from the town. While in a cottage on the edge of the company’s land, nine deputies entered. Two of these held up the companion with pistols, while the other seven forced his friend out of the cabin, beat him over the head with a pistol, knocked him down, kicked him, and did everything short of killing him.

An incident which has not received publication in the capitalist papers was the shooting of three Italian strikers, near Segundu, one of the other closely guarded camps. The men were not on the company’s land, but were returning over the hills from a hunting trip. They carried their guns and some rabbits, and were quiet and orderly. The deputies fired upon them from ambush, killing two and badly wounding the third. The funeral of the two was held at Trinidad, and 4,000 men, women and children, listened to the earnest words of an Italian organizer and to Mother Jones, who stirred the great audience of working people as few others can stir them. A heap of stones surmounted by a black cross now marks the spot where the men fell.

Such incidents are not entirely advantageous to a speedy and successful settlement for the company.

Some of the miners are unfortunate enough to own their own homes, although these, of course, are built on the company’s land. At one such little home at Berwynd two deputies called a few weeks ago and ordered the owner to clear out. He refused, saying that the house was his. “But the land isn’t, and you’d better go quick,” they returned.

The man’s daughter was in the home and was at the point of confinement, and therefore he begged and pleaded with the deputies not to put him and family out. The deputies answered by beating him over the head and throwing him out of doors. The daughter was taken ill and lay unconscious for four days.

It is these things that grind the souls and open the eyes of the miners to the naked facts of the class struggle.

The companies are making great efforts to open the mines. They are flooding the country with men from the army of unemployed and largely unorganized workers elsewhere. If these men refuse to work upon reaching Colorado and finding out the true state of affairs, the company is well satisfied to have them thrown for support upon the union. It is said to be openly advertised in the East that work is plenty in Colorado, and that if the men don’t want to work after they get there the union will take care of them. This has little effect in discouraging the strikers, however, for they know that the great majority of these imported workmen are entirely without knowledge of coal-mining, and that if the companies do succeed in getting them to work they will cause unlimited damage and loss. The experienced miners, almost without exception, are union men who have been secured through misrepresentation and who escape from the camps at the first opportunity.

A common experience is that told me by a weary and worn-out man who came into the union headquarters at Trinidad one evening.

“There was a carload of fifty of us from Chicago. They said there was no strike on and that there was a fine chance for our wives to start a boarding-house. We could make lots of money. So eight of us brought our wives along. They took us down to Raton (New Mexico) and then on in- to the camp at Willow Arroya. We pretty quick seen what was up, and me and another fellow made up our minds we’d get out quick. Some other fellows in there told us we’d have to work enough to pay for our railroad fare, but we thought some different. We couldn’t take our wives out then, but that night we watched our chance and slipped from house to house in the shadows, and we got past the company’s deadline before the deputy saw us. When he did he gave the cry, and two of them started chasing us. We dodged ’em, though, and got away. We was afraid to come back to the lower roads, so we sneaked around through the hills all night, guess we’ve walked fifty miles to get here. Of course, I am a union man and won’t scab. They’ll have to let our wives out, ’cause they can’t work and it will cost money to feed them. We’ll stay here until we get money enough to get back to Chicago.”

The Comrade began in 1901 with the launch of the Socialist Party, and was published monthly until 1905 in New York City and edited by John Spargo, Otto Wegener, and Algernon Lee amongst others. Along with Socialist politics, it featured radical art and literature. The Comrade was known for publishing Utopian Socialist literature and included a serialization of ‘News from Nowhere’ by William Morris along work from with Heinrich Heine, Thomas Nast, Ella Wheeler Wilcox, Edward Markham, Jack London, Maxim Gorky, Clarence Darrow, Upton Sinclair, Eugene Debs, and Mother Jones. It would be absorbed into the International Socialist Review in 1905.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/comrade/v03n06-mar-1904-The-Comrade.pdf