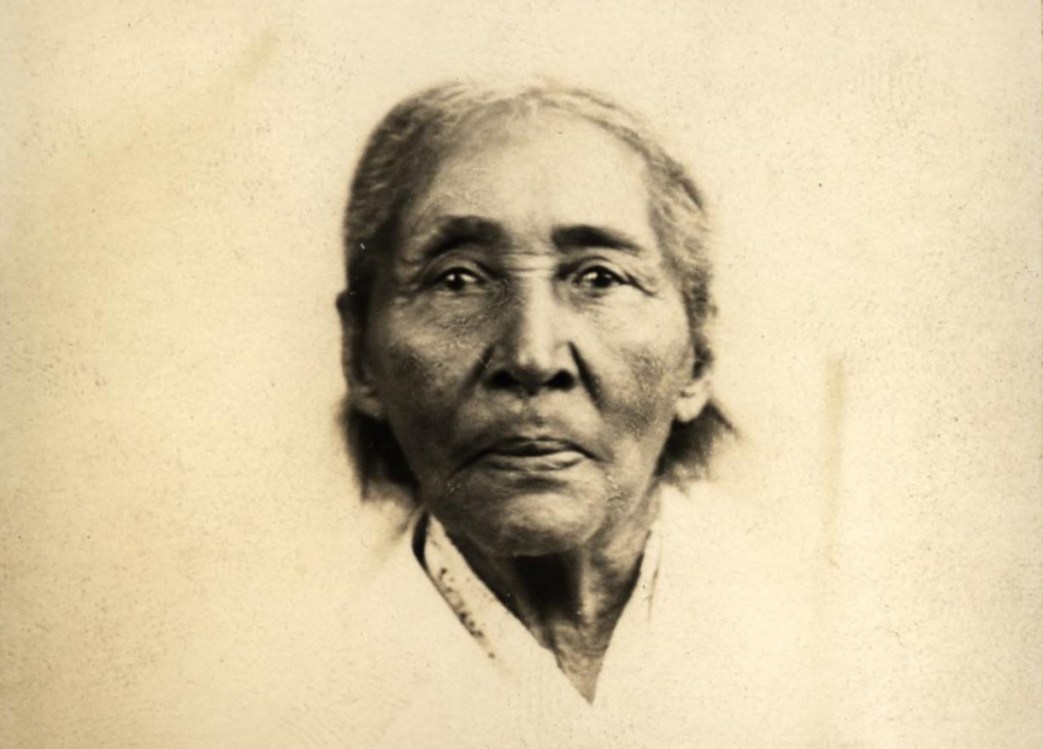

‘Our Civilization, Is it Worth the Saving?’ by Lucy E. Parsons from The Alarm (Chicago). Vol. 1 No. 28. August 8, 1885.

“Is our civilization of to-day worth saving” might well be asked by the disinherited of the earth. In one respect; tis a great civilization. History fails to record any other age like ours. When we wish to travel we fly, as it were, on the wings of space, and with a wantonness, that would have sunk the wildest imagination of the Gods of the ancients into insignificance. We annihilate time. We stand upon the verge of one continent, and converse with ease and composure with friends in the midst of the next. The awe-inspiring phenomena of nature concerns us in this age but little. We have stolen the lightening from the gods, and made it an obedient servant to the will of man; have pierced the clouds and read the starry page of time.

We build magnificent piles of architecture, whose dizzy heights dazzle us, as we attempt to follow with our eye along up the towering walls of solid brick, granite and iron, where tier after tier is broken, only by wonderous panes of plate-glass. And as we gradually bring the eye down story after story, until it reaches the ground, we discover within the very shadow of these magnificent abodes, the houseless man, the homeless child, the young girl offering her virtue for a few paltry dollars to hire a little room away up in the garret of one of them. And in the dark recesses of these beautiful buildings the “tramp,” demoralized by poverty and abashed by want, attempts to slink from the sight of his fellow beings.

Yet it was their labor that erected these evidences of civilization. Then why are they compelled to be barbarians?

For it is labor, and labor only, which makes civilization possible. ‘Tis labor that toils, and spins, and weaves, and builds, that another, not it, may enjoy. ‘Tis the laborers who dive into the unknown caverns of the seas, and compel her to yield up her hidden treasures, Which they know not even the value thereof. ‘Tis labor which goes into the trackless wilderness, and wields the magic wand which science has placed in its hand. Its hideous, hissing monsters soon succumb, and she blossoms like the rose. Labor only can level the mountain to the plain, or raise the valley to the mountain height, and dive into the bowels of the earth and bring forth the hidden treasures there contained, which have been latent through the changing cycles of time, and with cunning hand fashion them into articles, of use and luxury for the delight and benefit of mankind.

Now, why does this important factor in the arts of progress and refinement continue to hold a secondary position in all the higher and nobler walks of life? Is it not that a few idlers may riot in luxury and ease? Said few having dignified themselves with the title, “upper classes.”

It is this “upper class” which determines what kind of houses (if any at all) the producing class shall live in, the quantity and quality of food they shall place upon their table, the kind of raiment they shall wear, and whether the child of the proletariat shall in tender years enter the school house or the factory.

And when the proletariat, failing to see the justice of this bourgeoisie economy, begins to murmur, the policeman’s club is called into active service for six days in the week, while on the seventh the minister assures him that to complain of the powers that he is quite sinful, besides being a losing game, inasmuch as by this action he is lessening his chance for obtaining a very comfortable apartment in “the mansions eternal in the skies.” And the possessing class meanwhile. are perfectly willing to pay the minister handsomely, and furnish the proletariat all the credit necessary for this, if he will furnish them the cash for the erection of their mansions here.

Oh, workingman! Oh, starved, out; raged, and robbed laborer, how long will you lend attentive ear to the authors of your misery? When will you become tired of your slavery and show the same by stepping boldly into the arena with those who declare that “Not to be a slave is to dare and DO?” When will you tire of such a civilization and declare in words, the bitterness of which shall not be mistaken, “Away with a civilization that thus degrades me; it is not worth the saving?”

LUCY E. PARSONS. Chicago, August 3.

The Alarm was an extremely important paper at a momentous moment in the history of the US and international workers’ movement. The Alarm was the paper of the International Working People’s Association produced weekly in Chicago and edited by Albert Parsons. The IWPA was formed by anarchists and social revolutionists who left the Socialist Labor Party in 1883 led by Johann Most who had recently arrived in the States. The SLP was then dominated by German-speaking Lassalleans focused on electoral work, and a smaller group of Marxists largely focused on craft unions. In the immigrant slums of proletarian Chicago, neither were as appealing as the city’s Lehr-und-Wehr Vereine (Education and Defense Societies) which armed and trained themselves for the class war. With 5000 members by the mid-1880s, the IWPA quickly far outgrew the SLP, and signified the larger dominance of anarchism on radical thought in that decade. The Alarm first appeared on October 4, 1884, one of eight IWPA papers that formed, but the only one in English. Parsons was formerly the assistant-editor of the SLP’s ‘People’ newspaper and a pioneer member of the American Typographical Union. By early 1886 Alarm claimed a run of 3000, while the other Chicago IWPA papers, the daily German Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) edited by August Spies and weeklies Der Vorbote (The Harbinger) had between 7-8000 each, while the weekly Der Fackel (The Torch) ran 12000 copies an issue. A Czech-language weekly Budoucnost (The Future) was also produced. Parsons, assisted by Lizzie Holmes and his wife Lucy Parsons, issued a militant working-class paper. The Alarm was incendiary in its language, literally. Along with openly advocating the use of force, The Alarm published bomb-making instructions. Suppressed immediately after May 4, 1886, the last issue edited by Parson was April 24. On November 5, 1887, one week before Parson’s execution, The Alarm was relaunched by Dyer Lum but only lasted half a year. Restarted again in 1888, The Alarm finally ended in February 1889. The Alarm is a crucial resource to understanding the rise of anarchism in the US and the world of Haymarket and one of the most radical eras in US working class history.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/54013