A leading member of the Board of the People’s Food Commissariat on how the Revolution fed itself under War Communism.

‘The Food Policy of the Soviet Government’ by A. Svidersky from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 3 No. 18. October 30, 1920.

THE People’s Food Commissariat is in charge Commissariat; the general understanding is that of the state supply of the population. The leading organ of this Commissariat is, in accordance with the constitution of the R.S.F.S.R., a collegiate (board) appointed by the Council of People’s Commissars and is headed by a People’s Commissar appointed by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee.

In the localities the chief organs of the Food Commissariat are the Gubernia Provision Committees, the Uyezd Provision Committees and the District Provision Committees. (Gubernia, uyezd and volost are territorial sub-division, roughly corresponding to a state, county and village.) In regard to organization the local Provision Committee organs are connected with the local Soviets and with the Provision Commissariat. In addition to this an organization connection exists between the provision organs of the producing gubernias and the workers of the consuming gubernias. This is achieved in the following way:

The Uyezd Provision Committees consist of Uyezd Provision Commissars, who are elected by the uyezd councils and confirmed by the Gubernia Food Commissars, and of a collegiate (board) which consists of persons appointed by the Uyezd Food Commissars of the uyezd councils (Soviets). The Gubernia Provision Committees consist of Gubernia Food Commissars who are elected by the gubernia Soviets and are confirmed by the People’s Commissariat for Food Supply, and of a collegiate (board), whose members are appointed by the Gubernia Food Commissars and are confirmed by the executive organs of the gubernia Soviets. The District Food Committees are the provision organs supplying a number of voloets on the economic principle; these act in some places in lieu of the Uyezd Provision Committees. Their structure is on the same principle of organization as that of the Uyezd Food Committees and the Gubernia Food Committees.

The People’s Food Commissariat has the right of delegating authorized persons to all the District, Uyezd, and Gubernia Food committees with a view of suspending decisions which may be contradictory to the decrees and the instructions of the central authorities, or appear inexpedient from the point of view of general state interests. The People’s Food Commissariat has the right of including in every Uyezd Food Committee of a given gubernia, supplying grain, from one to one-half of the entire number of members of the Uyezd Provision Committee out of the number of candidates recommended by trade unions of workers, by Soviet organizations, and by various party associations of consuming gubernias who stand on the Soviet platform; in the same manner, representatives of Gubernia Food Committees of consuming gubernias may be delegated to every Food Gubernia one representative is sent from the capitals of Moscow and Petrograd, and one representative from the Army and the Navy; the complete number of the representatives of the Food Commissariat and of the consuming gubenv.as should consist of not less than one-third and not more than one-half of the entire number of the members of the Gubernia Provision Commissariats. The number of representatives of consuming gubernias in the Food organs of the producing gubernias is higher at the present time than the above-mentioned norm, and form approximately 80 per cent of the general number of the members of the Uyezd and Gubernia Boards of the Food Commissariat of the grain producing gubernias.

A special position in the general network of the organization of the food organs is occupied by the worker’s food detachments, the provision army, and the organs of labor inspection. The workers’ food detachments and the provision army taken together, represent one of the main levers in the activity of the People’s Food Commissariat and its local organs, especially with regard to the provision of grain and of forage.

The food detachments are formed by the Military Food Bureau of the All-Russian Council of Trade Unions. The functions of these detachments are as follows: 1) the registration of harvests and surplus grain; 2) operations directly connected with the dispatch of grain to the granaries; 3) propaganda work to get the peasants to deliver all the surplus grain to the state; 4) rendering assistance to the transport and so forth. During the grain campaign of 1918-1919 the People’s Food Commissariat had at its disposal 400 food detachments consisting of 13,000 men. For the present food campaign the number of food detachments was increased by another hundred which consisted of nearly 13,000 workers mobilized in the consuming gubernias.

The Food Army is entrusted with the duty of compulsorily obtaining all the surplus of grain in those cases where the owners decline to comply with the grain levy laid upon them. In the majority of cases, however, the Food Army is simply held in preparedness. Generally their mere presence in localities where grain is gathered is sufficient to insure the smooth delivery of all surplus, without recourse to compulsion. This was the prevailing state of things during the last grain campaign; it is also the prevailing state of things at the present moment. During the 1918-1919 season the food army numbered about 45,000 men. The increase of the food army for the current supply campaign is necessitated by the extension of the territory at the disposal of the state provision organs.

The Food Army is recruited from volunteers and those liable to military service, but whose state of health renders them unfit for such. From the point of view of organization the Food Army in its structure is similar to that of the Red Army, being subject to all the decrees applying to the latter and it may be utilized for military purposes should the need for this arise. The organs of labor inspection are formed of class conscious intelligent workers, recommended by the trade unions. These are formed by the military Food Bureau (of the trade unions) and are under its supervision, but their activity is guided by the People’s Food Commissariat. The task of the organs of labor inspection is to carry out class control over the activity of the Food Commissariat’s institutions as well as of the local food organizations. Recently the Provision Labor Inspection merged with the Workers’ and Peasants’ Inspection which took the place of the State Control.

This is the business apparatus of the People’s Food Commissariat and of its local organs. This is not a mere technical apparatus which collects grain by way of monetary payment at fixed state prices or by way of exchange of goods, collecting at the same time all other food products and articles of general consumption, — but it is an organ m which is ill every respect adapted to obtain grain and to carry on an organized and systematic struggle for the supply of food to the starving population.

Until recently the People’s Food Commissariat in the center and the Food Committees in the localities, in addition to carrying out the functions of supply, also carried out all the functions of distribution. For this reason as far as their structural organization was concerned the food organs had to take into consideration the execution of tasks connected with all matters of distribution. At the present time, in accordance with a decree of the 20th of March, 1919, the functions of distribution are entirely transferred to the cooperative societies whilst the People’s Food Commissariat, as a state organ, retains the right of control over the activity of the newly created distributing organizations.

These problems, the practical solution of which is entrusted by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and by the Council of the People’s Commissars to the People’s Food Commissariat and its local organizations are fully formulated by a number of decrees published consecutively during the period of almost three years’ existence of the Soviet Government. By a decree of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee dated May 27, 1918, the People’s Food Commissariat was instructed to unite into one organ the entire supply of the population with articles of first necessity and of consumption, to organize on a national scale the distribution of these goods, and to prepare the transition to nationalization of Trade and Industry. By a later decree of the Council of the People’s Commissars dated November 21, 1918, the Food Commissariat was instructed to organize the supply of all products serving personal and domestic needs; the aim of this decree was the substitution of the private commercial apparatus by a systematic supply of the population with all necessities out of the Soviet cooperative distributing depots.

The above-mentioned decrees do not by far exhaust all the Soviet legislation by which the activity of the Food Commissariat is defined. But they mark the principal stages in the development of the functions of the food organs. Both decrees emphasize the gradual change of the Food Commissariat from a provision organ in the narrower sense of the word into an organ for the state supply of the population.

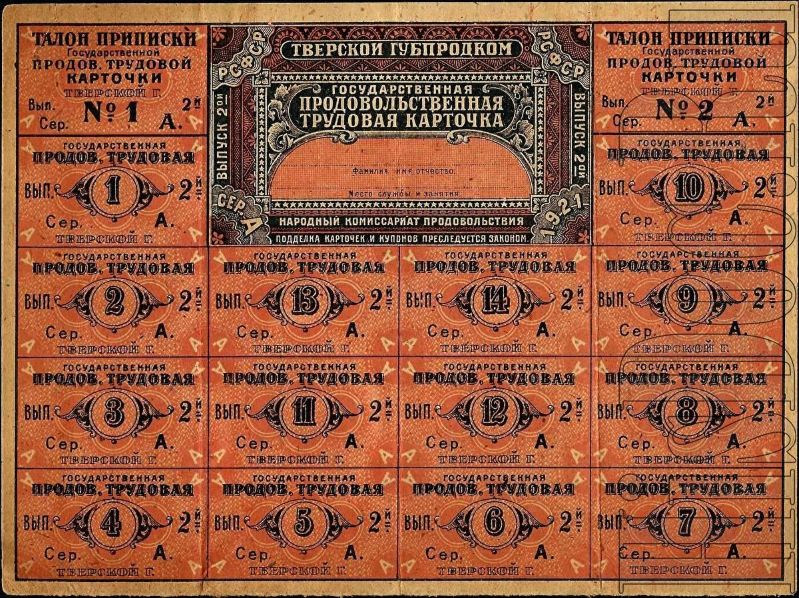

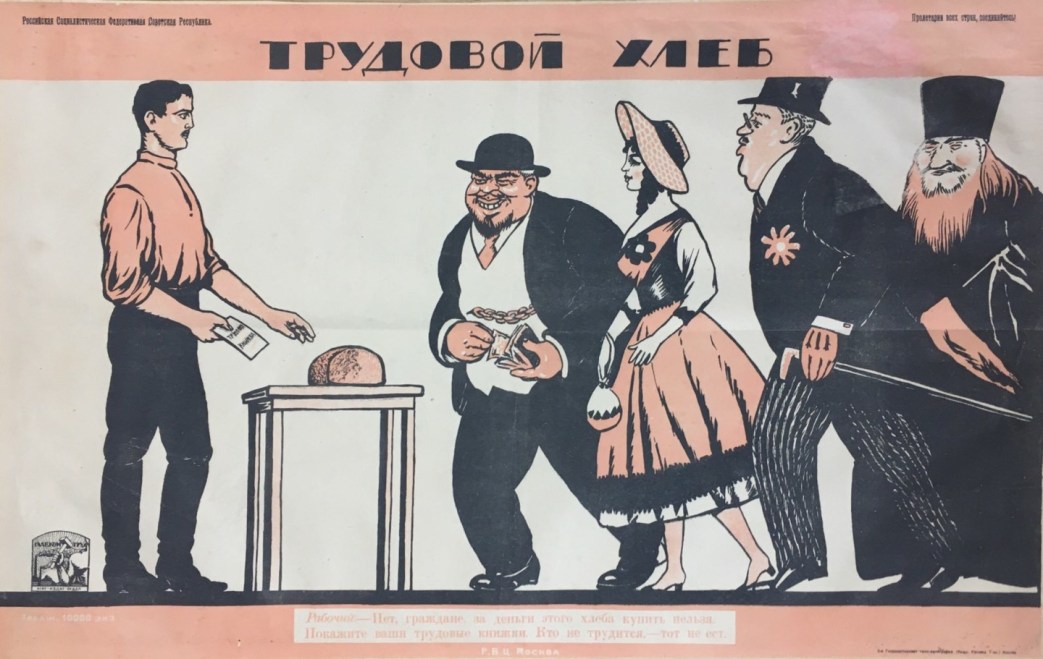

As regards the principal instruction which during the last two years were for various reasons and in various forms given to the People’s Food Commissariat by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee and by the Council of People’s Commissars, it must be pointed out that these instructions amounted and continue to amount to the following: 1) the registration of articles of provision and of general consumption; 2) the institution of state monopoly for the chief articles of alimentation, and 3) distribution in accordance with the principle of class distinction: he who does not work neither shall he eat. A certain clarity was introduced in these basic postulates by the All-Russian Central Executive Committee’s decree dated January 21, 1919: it was definitely pointed out which particular products constitute the monopoly of the state; these were grain, forage, sugar, salt and tea; which kind of articles are to face collected on a state scale but not on monopoly principles, these included all meat products, fats, fish and so forth, and which may be obtained by large labor associations and freely brought to town for free sale in the open markets; to these categories belong potatoes and a few other articles.

The decree of January 21 clearly defined the extent of the authority of the food organs by the establishment of the two categories of monopolized and ordinary products. As it happened, this at the same time meant moving a step backward as far as the state supply was concerned. The same decree instructed the People’s Food Commissariat with taking measures to improve its supply apparatus for the purpose of extending the state supply also to ordinary products. For the purpose of fulfilling this regulation a decree was issued on August 15, 1919, making the supply of potatoes a state monopoly and prohibiting to any organization, excepting state organs, the purchase of products which have by the decree of January 21 been attributed to ordinary products; this prohibition extended to five gubernias. Thus one of the chief principles of organization of state supply of the population was confirmed afresh.

Our food policy found its clearest expression in the decrees and instructions with regard to the supply of grain. The decree issued by the All-Russian Executive Committee and published on May 13, 1918, the purpose of which was to confirm the hard and fast rule regarding the grain monopoly October 30, 1920 and making it incumbent upon every owner to turn over all supplies, excepting the quantity required for sowing and for personal consumption to the state food organs according to the established levy ; this decree called upon all the laboring and poor peasants to unite immediately for the purpose of a resolute struggle against the grain profiteering peasants. The same decree endowed the People’s Food Commissariat with extraordinary prerogatives including the right of applying armed force in cases where resistance is offered in the collection of corn or other food products. The main idea of the decree of May 13 is still more vividly expressed in the appeal of the Council of the People’s Commissars issued to the population towards the end of May, 1918. Not a single step backward should be made with regard to the bread monopoly, was said in this appeal. Not the slightest increase of the fixed prices for grain! No independent storing of grain! All that is disciplined and class conscious — into a united organized food front! Strict execution of all the instructions of the Central Government! No independent activity! Complete revolutionary order all over the country. War to the profiteers!…

Not satisfied with the instructions regarding the principal idea of our food policy, the All-Russian Central Executive Committee by a decree dated June 11, 1918, on the organization of the supply of the village poor, has defined the form of organization in which the line of conduct towards the profiteers as well as to the sections of the village population who are guilty of hiding their surplus of grain are to be treated. Although subsequently, by a special regulation of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee, the established forms of organization have been removed, in its principal features the food supply policy remained as before and is remaining so until the present time. As in the past the policy is now based upon the organization of the proletarian and semi-proletarian elements of the villages against the profiteers, only under a different form, i.e., in so far as the obligatory grain levy applies also to the middle peasantry as long as it has a surplus of grain.

Of special significance in the food policy of the Soviet Government is the system of exchange of goods, which serves as a means of extracting the grain surplus from the villages: this policy by the way was also utilized by the Provisional Government. The policy of exchange of goods was first practically realized when, in accordance with a regulation of the Council of the People’s Commissars passed on the 25th of March, 1918, the People’s Food Commissariat was financed for that purpose to the extent of one milliard one hundred and sixty millions of rubles; later on, on the 2nd of April of the same year, a special decree was issued regarding exchange of goods; here all articles subject to goods exchange were enumerated and at the same time a special principle was established upon which all goods exchange is to be carried on; this principle consisted in attracting the poorer peasants to the organization of exchange of commodities and the obligatory transfer of goads sent in exchange for grain to the disposal of the volost or district organizations for the purpose of its further distribution amongst the population in need of these goods. The establishment of this principle was dictated by necessity, as it was proved in practice that the exchange of grain leads to the accumulation of goods in the hands of the profiteers to the great disadvantage of the poor section of the peasantry.

A few months later it became necessary to introduce one more important addition into the system of goods exchange. It appeared that the decree of the 2nd of April is eluded in various ways by the grain owners; this was largely facilitated by the fact that the profiteers and the richer sections of the rural population were enabled to obtain the necessary goods from private sources and thus were not driven to the necessity of turning over their surplus to the state organs with a view of obtaining goods from them, which goods were in addition given, to the disposal of the volost and village organizations. In order to deprive the grain owners of the opportunity of resorting to this dishonest method a decree was published on the 8th of August, 1918, concerning obligatory exchange of goods; the first paragraphs of this decree is to the following effect: For the purpose of facilitating the development of the decree issued on the 2nd of April regarding exchange of goods — in all villages and uyezd established for exchange of goods of the industrial gubernias as well as of ” all non-agricultural products exclusively for grain and other food products, as well as for hemp, flax, leather and so forth; this established system for the exchange of goods applies to cooperatives as well as to all state, public, and private institutions.

The decree concerning obligatory exchange of goods, which was necessitated by the need of storing all grain in the state granaries has in addition to the grain monopoly, also marked a way for the solution of one of the greatest problems in the transitional period from capitalism to Socialism — the problem of establishing definite economic relations between the industrial workers and the agricultural workers. It became necessary to proceed further along this road the more so that for the last two years the state reserve of goods shrank to a great extent. The next progressive step with regard to goods exchange was made on the 5th of August, 1919. The publication of a decree followed, by virtue of which: for the purpose of furthering and combining the decrees of the 2nd of April and of the 8th of August, 1918, concerning exchange of goods, and for the purpose of storing raw material and fuel for the reestablishment and the supply of the village population of the R.S.F.S.R. by the organs of the People’s Food Commissariat and the cooperative societies with the produce of mining and manufacturing industries as well as with bread and other food products, is conducted on the sole condition of the delivery to the state organs of all the agricultural and home industry produce by the rural population.

To sum up all the above, the basis of the Soviet food policy may be defined in the following manner: 1) the introduction of the principle of the State supply of the population with food and articles of general consumption, 2) the establishment of a monopoly for the principal food products, 3) the development of state storing with regard to non-controlled products, 4) the introduction of compulsory collective exchange of goods in the rural districts for all products of agriculture and of home industry, 5) the establishment of a compulsory levy upon the population for the delivery of the surplus of grain and the more important products of agriculture, 6) a war for bread and for other products and articles of general consumption necessary to the town against the profiteering peasant elements, which is waged in alliance with the proletarian and semi-proletarian sections of the villages and, 7) favorable terms of supply to the workers as against the non-working sections of the population.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v3n18-oct-30-1920-soviet-russia.pdf