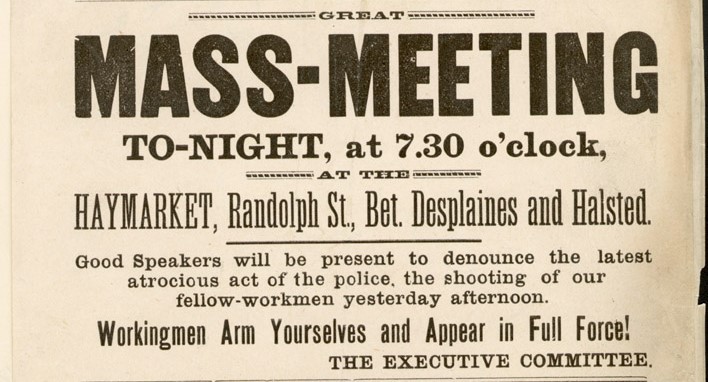

A piece of history on the road to Haymarket. As the May 1, 1886 general strike for the eight-hour day approaches, Chicago radicals gather to proclaim they will enforce the eight-hour day on May 1 regardless of law. The meeting is addressed by Paul Grottkau, August Spies, and Samuel Fielden among others.

‘Eight Hours’ from The Alarm (Chicago). Vol. 2 No. 5. October 17, 1885.

TRADES UNIONS GATHER IN MASS MEETING AT TURNER HALL.

They Prepare for the Inauguration of the Eight-Hour Work Day.

Resolutions to Arm and Defend Themselves Against the Starvation, Prisons and Cold Steel of Capitalists.

RESOLUTIONS ADOPTED.

The Central Labor union, composed of eleven Socialistic trade unions of this city, announced a mass meeting of the wage workers of Chicago, in Twelfth Street Turner Hall, last Sunday afternoon by issuing the follow circular:

The Central Labor union opens the campaign for the reduction of industrial wage work to eight hours a day. Prepare to enforce it by all resources of organization and to punish the cruel taskmasters for all over work of degraded wage-slaves!

The toiling masses create and preserve all wealth and prepare themselves to reap the whole reward of their labor after getting rid of the parasitic drones of society.

Three hours daily labor creates what is now paid to us as wages in money, and seven hours more work is taken from our daily toil to pay profit, rent, interest, “management” and other exactions to accumulate by grand larceny, private capital to enslave and starve us under the sanction of religion, law and order. Let us shake off this slavish fear of the power of capital! Our self-imposed robbers are strong only in our voluntary submission to their autocratic impositions. Whatever they own is taken from us. Whatever power they wield is usurped as against voluntary self-abnegation on the part of the toiling masses. Eight hours daily labor with all modern improvements of machinery and subdivision of labor will furnish more goods and services than the market demand can take for profitable distribution. Over-work for the employed workers causes an army of surplus idlers and in the scramble for a chance of employment reduces wages to a point where civilized people are displaced by human beings without civilized habits of life as is done by the mining bosses, factory lords and merchant princes. We are a law unto ourselves and will introduce the eight-hour system in spite of all knaves and cowards who keep up a heavy fire in our rear, while we fight our capitalistic enemy in front. Workers of all useful occupations, rally under the red flag of the proletarian revolt! We demand equal rights and duties for all toilers in useful employment; special privileges for none!

Able speakers will explain what we mean by this eight-hour agitation.

CENTRAL LABOR UNION.

About 600 persons assembled in Turner Hall in response to the call. Mr. A. Belz presided, who stated that the object of the meeting was to consider the inauguration of the proposed 8-hour working day on the 1st day of May, 1886.

Samuel Fielden was introduced as the first speaker. He gave an exhaustive review of the unsatisfactory condition existing between capital and labor, evidenced by the frequency of strikes resulting from the constant tendency to diminish rates of wages and extend the hours of labor. He dwelled on the “grinding tyranny of capital,” which makes it difficult for the working masses to achieve the emancipation of labor. The speaker referred to the St. Louis strike and the policy followed by the owners of the Pullman car works to prevent the organization of skilled labor, although the capitalists themselves claim the right to organize and band themselves together hold labor in still greater and growing subjection. The Saginaw Valley lumber owners ask their employes to enter into a compact never to appeal even to the law, whatever oppression they may have to confront before they are allowed to work at all. The capitalists could render the satisfactory working of the eight-hour law impossible. The laws were made only for the iron barons of Pennsylvania, the lumber barons of Michigan, and the Jay Goulds and Vanderbilts, who have extracted millions of profit from the labors of workingmen. The real and effective means to ameliorate the condition of labor was to abolish private property, and so destroy competition. Ben Butler stated at Grand Rapids that he got more out of his employes by reducing their hours of labor than he did when they were working longer hours. For these reasons the speaker was opposed to the eight hour law. It was not to relieve, but to make further profit out of their employes that employers here and there tried the experiment of reducing the hours of toil. He said that if they would abolish the government they could do something for themselves.

The wage workers have not the means of making a prolonged fight. The employers have. They therefore hold the key to the situation. The legislature of Michigan at its last session passed a tens hour law. Yet the lumber film of A.W. Wright & Co., of East Saginaw, compelled their lumber camp employes to sign a contract waiving any rights under this act as a precedent to employment. In Illinois there has been an eight-hour law on the statute book for nearly 20 years, yet it is a dead letter. These things, together with the action of the Labor Federation, show that the wage workers must look beyond the law and to themselves to sustain their rights.

Mr. A.W. Simpson said the eight-hour law scheme was as fallacious as all the other schemes of the orthodox political economists for benefiting the laboring classes. The law is good, however, for it will give workingmen more time to think of their wrongs. It will also reduce the hours of a day’s labor by two. But where is the money in it to the laborer? The “boss” will not pay out of his profits the increased amount required for wages, unless by raising the price of the manufactured article to the consumer, the workingman. “But,” said he, “if an increase of wages, which is synonymous with a reduction of the hours of labor, is due the laborer, why wait for the enforcement of the eight-hour law? If you can get it out of the manufacturer’s profits any time, get it out now in the shape of a real advance. But you do not do this because the “boss” has the advantage of you. Trade unionism is simply organized selfishness. It proposes to assist those laborers who are in the trades unions at the expense of those who are not. Socialism claims that an injury to one is an injury to all. The enforcement of the eight-hour law, however, will have a good moral effect. It will give trades unionists and other workingmen more time to attend Socialist meetings and thus learn Socialism.

Mr. Paul Grottkau addressed the meeting in German. He said the development of machinery and of applied science had so developed the producing power of labor that there was, in fact, general over-production. This made necessary the idleness of some, or shorter hours of labor for all. The eight-hour law is an advance, for it shows an awakening of the people to their rights. The demand for eight hours as a day’s work is not a demand for all the people’s rights, but only for a part of them. If they demanded all their rights they would demand the whole product of their labor, and the abolition, not of capital, but of private capital. The eight-hour law is only temporarily salutary in its effects. With such a limit to the day’s work, development of machinery and science will go on at an accelerated rate. Children’s and woman’s labor will take a more prominent place, and we will soon be confronted with the same state of overproduction that we have now. The whole social system must be changed, and that can only be done by organization and agitation

Mr. August Spies was introduced at this point and offered the following resolutions:

WHEREAS, A general move has been started among the organized wage-workers of this country for the establishment of an eight-hour work day, to begin on May 1, 1886; and

WHEREAS, It is to be expected that the class of professional idlers, the governing class, who prey upon the bones and marrow of the useful members of society, will resist this attempt by calling to their assistance the Pinkertons, the police and state militia; therefore, be it

Resolved, That we urge upon all wage-workers the necessity of procuring arms before the inauguration of the proposed eight-hour strike in order to be in a position of meeting our foe with his own argument, force.

Resolved, That while we are skeptical in regard to the benefits that will accrue to the wage workers from the introduction of an eight-hour work day, we nevertheless pledge ourselves to aid and assist our brethren in this class struggle with all that lies in our power as long as they show an open and defiant front to our common enemy, the labor devouring class of aristocratic-vagabonds, the brutal murderers of our comrades in St. Louis, Lemont, Chicago, Philadelphia and other places. Our war cry be: “Death to the enemy of the human race, our despoilers.”

The reading of these resolutions was received with round after round of applause, and the chair was about to put them to a vote, when Mr. J.K. Magie arose and said that he understood a discussion of them was in order. He denounced the revolutionary character of the resolutions. He believed that six hours’ daily labor was enough. This was the best form of government that ever existed. If there are abuses there is a proper way to correct them. Eighty per cent of the voting population are working people. They should strike with the ballot, not with the bullet.

Magie’s remarks were received with a storm of disapproval, and shouts of “rats” from all parts of the hall.”

P.J. Dusey defended the resolutions, in his peculiarly energetic style, closing with the declaration, “The bullet brought this nation into existence, and by the eternal God the bullet shall make us free men or dead men.”

August Spies supposed that Mr. Magie did not like the terms in which the members of the government were referred to. The reason of this was that Mr. Magie was one of those political vagabonds himself. There were 9,000,000 of the people engaged in the industrial trades of this country. There were but 1,000,000 of them as yet organized, while there were 2,000,000 of men unemployed. To make the movement in which they were engaged a successful one it must be a revolutionary one. Don’t let us, he exclaimed, forget the most forcible argument of all–the gun and dynamite.

The resolutions were then put to the meeting, and carried with only a few dissentients.

The meeting then adjourned.

It is the purpose of the Central Labor Union to continue the agitation, by holding mass meetings at different times throughout the coming winter, to strengthen the movement for the successful inauguration of the eight-hour work day next May.

The Alarm was an extremely important paper at a momentous moment in the history of the US and international workers’ movement. The Alarm was the paper of the International Working People’s Association produced weekly in Chicago and edited by Albert Parsons. The IWPA was formed by anarchists and social revolutionists who left the Socialist Labor Party in 1883 led by Johann Most who had recently arrived in the States. The SLP was then dominated by German-speaking Lassalleans focused on electoral work, and a smaller group of Marxists largely focused on craft unions. In the immigrant slums of proletarian Chicago, neither were as appealing as the city’s Lehr-und-Wehr Vereine (Education and Defense Societies) which armed and trained themselves for the class war. With 5000 members by the mid-1880s, the IWPA quickly far outgrew the SLP, and signified the larger dominance of anarchism on radical thought in that decade. The Alarm first appeared on October 4, 1884, one of eight IWPA papers that formed, but the only one in English. Parsons was formerly the assistant-editor of the SLP’s ‘People’ newspaper and a pioneer member of the American Typographical Union. By early 1886 Alarm claimed a run of 3000, while the other Chicago IWPA papers, the daily German Arbeiter-Zeitung (Workers’ Newspaper) edited by August Spies and weeklies Der Vorbote (The Harbinger) had between 7-8000 each, while the weekly Der Fackel (The Torch) ran 12000 copies an issue. A Czech-language weekly Budoucnost (The Future) was also produced. Parsons, assisted by Lizzie Holmes and his wife Lucy Parsons, issued a militant working-class paper. The Alarm was incendiary in its language, literally. Along with openly advocating the use of force, The Alarm published bomb-making instructions. Suppressed immediately after May 4, 1886, the last issue edited by Parson was April 24. On November 5, 1887, one week before Parson’s execution, The Alarm was relaunched by Dyer Lum but only lasted half a year. Restarted again in 1888, The Alarm finally ended in February 1889. The Alarm is a crucial resource to understanding the rise of anarchism in the US and the world of Haymarket and one of the most radical eras in US working class history.

PDF of full issue: https://dds.crl.edu/item/54015