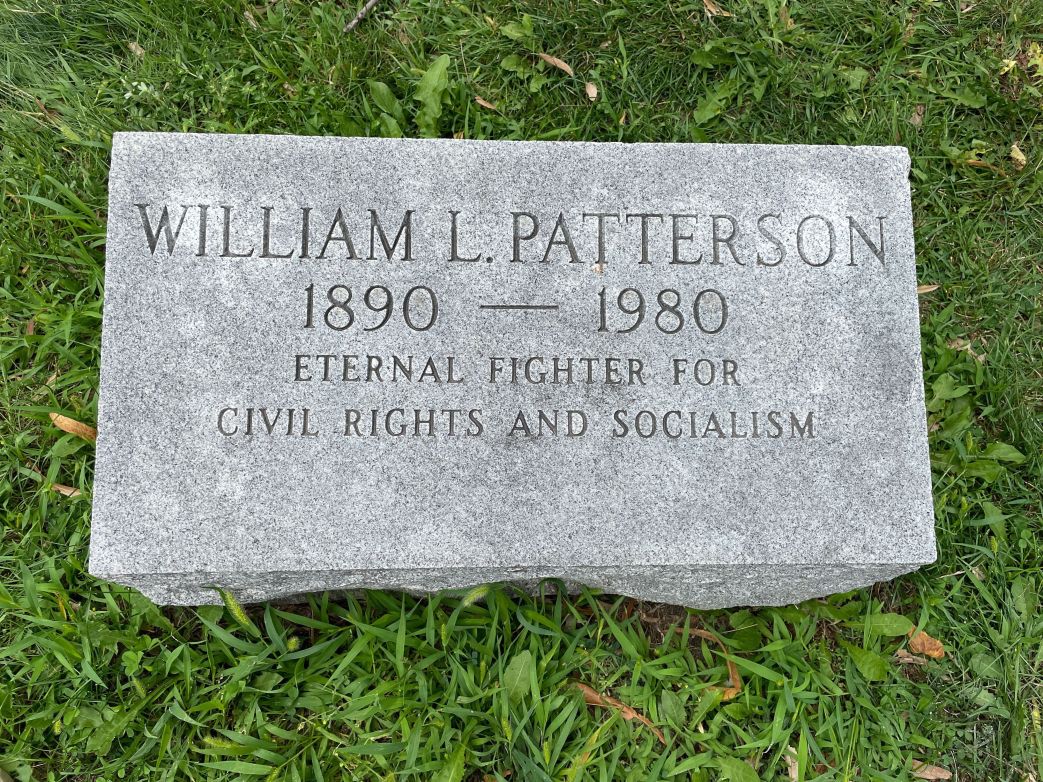

In one of his first articles written for the Daily Worker, Patterson refutes the proposition that Communists were responsible for radicalizing Black workers, rather it was the experience of U.S. society itself. A young Black lawyer, William L. Patterson, was passionately engaged the Sacco and Vanzetti case which brought him into the Communist Party in 1926 through its American Negro Labor Congress and International Labor Defense, which he would eventually lead.

‘The Negro and Soviet Russia’ by William L. Patterson from The Daily Worker. Vol. 4 No. 264. November 18, 1927.

ABOUT the 29th day of June of this year, the metropolitan press, ably led by the notoriously reactionary Herald-Tribune, gave considerable space in its columns to what it alleged was a discovery of tremendous importance. It had obtained evidence, it contended, which was calculated to uncontrovertibly prove that Soviet Russia was engaged in the damnable business of attempting to bring to the Negro in America a realization that under the present social order his existence in this land of liberty must forever be a precarious one, and was advising him that if he ever expected to realize any of his long cherished hopes for equality before the law; recognition socially as a human being, rather than continued and almost unprecedented mortification and degradation as a social pariah; acceptance on the economic field as one whose services when equal to those of his fellow workmen entitled him to equal compensation, he should at once undertake to supplant the present controlling social forces by those more sympathetic to his sensibilities and more responsive to his social needs.

The dailies did not rely upon generalities, but cited concrete examples of the nefarious activities of those “Bolsheviks” among the poor and easily misguided blacks. Money had flowed like water, other alluring inducements had been made to secure their adherence to Bolshevik philosophy, and there was some danger that they might succumb to these blandishments.

The Mississippi Flood.

These stories appeared about the time some few Negroes in Northern states were attempting to effectively agitate for a national policy of relief among the Mississippi flood victims, eighty-five per cent of whom were black, which policy they humbly suggested should seek to elevate the Negro in the Delta region one degree above the conditions of slavery, the lot which the world had learned thru this catastrophe was still his. The government’s representative to the stricken district, Mr. Herbert Hoover, had declined to object to the continuance of conditions as he found them; in fact, by the manner in which he acquiesced, he enhanced his value as presidential timber.

The American Negro Labor Congress had called a flood protest meeting at the Abyssinian Baptist Church in Negro Harlem, seeking to elicit a vigorous word of condemnation against the administration of relief funds generally, and the pernicious conditions existing in refugee camps particularly. With the belief that its purpose would be sympathetically interpreted, the press had been invited. But the efforts of the congress served only to arouse the ire of that part of the capitalist press which becomes virulent when a Negro dares to believe that conditions exist against which he has just cause to complain, or if it is obvious such conditions do exist, sees red when a Negro has the temerity to decry their continuance. The newspaper report of this meeting was a classic.

Distortions and Inaccuracies.

We return to these articles not so much to call attention to the glaring distortions and inaccuracies of the dailies since most of those who will read this are well aware of the capitalist press’ possession of these characteristics, or to expose the utter demoralization of that part of the Negro press which copied these articles verbatim. We return to prove that the condition of the Negro in America is not improving and for the purpose of revealing to the masses of Blacks the peril of that position today.

Along with the press attacks, to be considered as being in the same category and certainly of equal importance in awakening the masses of Negroes to the dire necessity of a new Negro policy was the Locke-Stoddard debate “Can America Absorb the Negro?” carried in the columns of the October Forum. True, many of the so-called Negro intelligentsia took issue with the learned Mr. Locke but the great majority of them accepted his battle cry “Grant us of the cultured elite, equality and deliver unto us our masses and we will placate them.” Verily, for a mess of pottage the house slaves would act guard over the field hands. If the younger members of Negro literati are content with this type of leadership we despair of their future and if the millions of Negro peasants and workers in the South can read their salvation between the lines of the argument presented by Mr. Locke in his attempt to maintain the affirmative of the issue then as a clairvoyantic performance their reading is unsurpassed. Gary, Indiana, is but cumulative evidence of the existence of shoals ahead.

The Position of the Negro.

Beyond a shadow of doubt the position of the Negro in America demands scientific and painstaking analysis. In whatever direction one may turn it is to discover a struggle destructive of social stability, wasteful and demoralizing in its nature, raging between whites and blacks.

Those least observant appreciate its existence only when it bursts forth in the blind fury of an East St. Louis, a Washington or a Chicago riot. In the South, the Negro exists, a so-called citizen of states which persistently refuse to afford him protection of life, to grant him liberty, other than of a limited degree, or to permit his pursuit of happiness save in a highly circumscribed manner and along lines approved by the proponents of biracialism (all white Southerners are such save at night). In the national capital, we find jim-crowism rampant in most of the departmental offices; and a Dyer Anti-lynching bill is blocked in the senate. In the north we now find republicans as well as democrats allied with the klan. Is it not amazing that the Negro is beginning to think. The operation of objective forces makes thought a vital necessity of an avenue of escape is to be discovered.

Lynchings Advertised.

The southern oligarchy continues its night-riding. Lynchings now find advertising space in the press and the scions of the best families now openly assume the leadership of mobs; throughout the length and breadth of the south there is no court of law which will consistently convict for offenses committed against Negroes. The duly elected. functionaries of the people show in unmistakably manner their hostility toward blacks.

Does Not Stand Alone.

Negro labor is sharp, there is little unionization and between blacks and whites no working-class solidarity. And the south does not stand alone. Many and devious are the ways by which the northern white assures the Negro that only when the cry is “War for Democracy” is he a full-fledged citizen.

Those who decry what they describe as radical tendencies among Negroes fail to appreciate that he too can read of a political philosophy which when put to practice bring forth the seven hour day, unemployment insurance, old age pensions, a social order where the women are relieved from their employment two months before child birth, remaining away until two months, after, and are paid in full during this period. Many other advantages under this new regime might be recited and the Negro is taking heed of it all. A new social order here is imminent. The Negro needs no special inducement to be called to the ranks.

The Daily Worker began in 1924 and was published in New York City by the Communist Party US and its predecessor organizations. Among the most long-lasting and important left publications in US history, it had a circulation of 35,000 at its peak. The Daily Worker came from The Ohio Socialist, published by the Left Wing-dominated Socialist Party of Ohio in Cleveland from 1917 to November 1919, when it became became The Toiler, paper of the Communist Labor Party. In December 1921 the above-ground Workers Party of America merged the Toiler with the paper Workers Council to found The Worker, which became The Daily Worker beginning January 13, 1924. National and City (New York and environs) editions exist.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/dailyworker/1927/1927-ny/v04-n263-NY-nov-17-1927-DW-LOC.pdf