A 1910 editorial from Solidarity on how craft prejudices among ‘skilled’ white workers against the ‘unskilled’ overlapped with their race and national prejudices.

‘Gompers and the Race Question’ from Solidarity. Vol. 1 No. 50. November 26, 1910.

Solidarity has received the following note from a reader in Chicago:

“You have undoubtedly read the brutally frank remarks ‘Lord’ Gompers made regarding our unfortunate fellow citizens of black color. I am an old man, have lived in this so-called republic for 58 years, have seen it as low as a corrupt and unprincipled people could make it go; but I have noted at all times a number of higher and finer souls who have striven to lift it out of the mire. Today I look despairingly for the beacon lights upon whom the nation might look in its hour of distress. I remember many a harsh, inhuman, eye, brutal expression regarding those of our fellow beings whom the superior race exploited in a manner that called forth the condemnation of the best men and women in this and other countries. But I remember nothing more brutal, more heartless, more arrogant, more foolish than the proposal of this autocrat, this ‘philosopher of right,’ this firm believer in the ‘brotherhood of man,’ whose every word belies his fine phrases that ill cover up the real object, purpose and tendency of this impudent program. I hope the members of the labor unions are not as unjust, inhuman, impudent, cruel, what you please to call it, as their star leader. If they are, the condemnation of conscientious, just, decent mankind will apply to them also. I beg of you to take note of his utterances and give them the setting they deserve. I have no faith in the socialists doing it, as they ought to. Berger is getting to be a diplomat already.”

JACOB EGBERTH

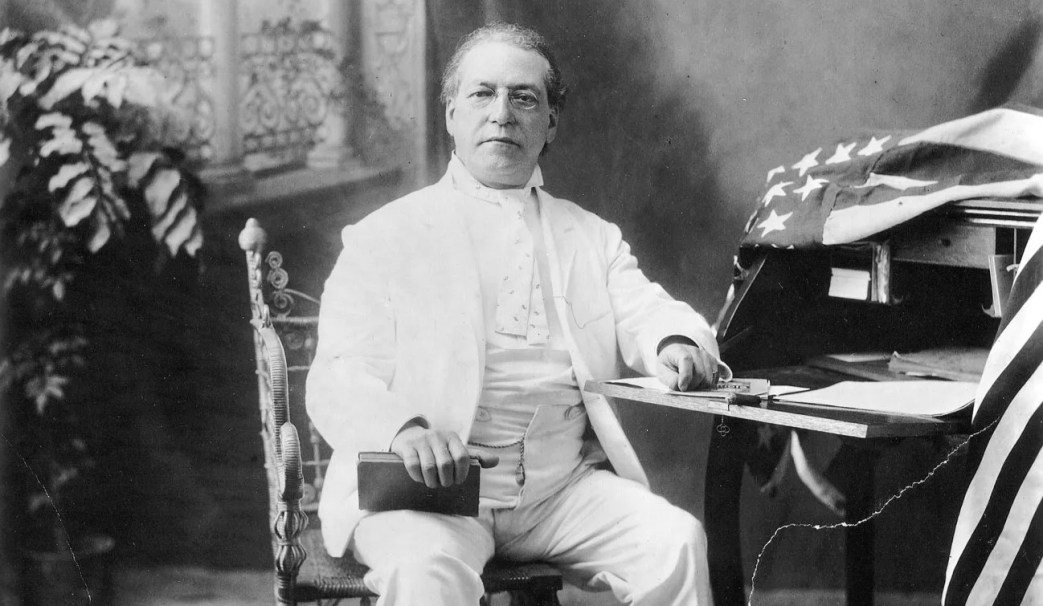

The above allusion is to an alleged statement by Gompers at a reception on November 18, in St. Louis, given by the local A.F. of L. to the delegates to the national convention of that body. In a speech on the occasion Gompers is reported to have touched upon the race question, in which he is declared to have said that “the negro is not far enough removed from slavery to understand human rights,” and may, therefore, be legitimate subjects for discrimination by the trades union movement.

Gompers denies the statement thus imputed to him, and declares that he made a special appeal for the organization of negroes into the trades unions, and only incidentally remarked in his speech that “in our efforts to win negroes for the unions’ cause, the fact should not be lost sight of that American negroes are only half a century removed from slavery and consequently are deprived of advantages that white men have enjoyed for centuries.”

This denial will not save Gompers or the A.F. of L. from the charge of race discrimination. On the contrary, the very form of the denial but shows a desire to justify such discrimination on the part of the craft union movement. The whole history of the American Federation of Labor adds emphasis to the point, not only as regards the negro, but also with reference to every foreign white worker as well. Race and nationality discrimination is a patent fact all along the line. The A.F. of L. is an “American” organization in the narrow “Yankee” sense of that term. And it is so because the A.F. of L. is primarily based upon the “aristocracy of skill.” The skilled workers, being originally native white Americans, found thereby a lasting and perfectly justifiable (to them) reason for their “patriotism” and their aversion to foreigners and native blacks who were just emerging from chattel slavery.

As a consequence of this situation and environment, each nationality and foreign workmen in turn had to fight for a place in the craft union ranks in America. And these “favored” ones from foreign lands, who finally fought their way into the “organized aristocracy of skill” also became “patriots” and in many cases have outdone the natives in their opposition to the “pauper labor of Europe,” the “yellow peril” and the “backward negro.”

Meanwhile industrial and social development have gone far beyond this narrow viewpoint of the trades union. The development of machinery, the expansion of industry, the removal of skilled processes, have enabled and compelled the employing class to scour the earth in search of all nations of unskilled labor, in every factory, store, and farm in America. Race prejudice has been fanned into flame and kept alive by capitalist agents, in order to keep the workers divided and at each others’ throats.

The A.F. of L., far from trying to remove the race prejudice, has accentuated it by its form of organization, and by its attitude towards the unskilled workers, who make you the overwhelming mass of wage slaves, and who remain almost totally unorganized. The A.F. of L. only makes a bluff at organizing the unskilled when some other organization seriously undertakes that work, and thereby invades the field of the American labor movement. But it is ONLY A BLUFF on the part of the A.F. of L., because the organization of the unskilled would destroy the craft union and the official machine that now holds it together. The negro for the most part still belongs to the category of “unskilled,” and therefore, apart from his color, is an object of discrimination by the craft union.

This state of affairs cannot be wiped out by appeals to sentiment, however justifiable they may be. It can only be removed by education and organization along the lines of revolutionary industrial unionism as proposed by the I.W.W. The latter calls upon all wage workers, regardless of color, nationality, religion, politics, or any other consideration except that they are WAGE WORKERS–skilled and unskilled–to unite in one CLASS union on the industrial field. This appeal is not based on “sentiment” or “philanthropy,” but on economic (bread and butter) interests. Leaving the negro or the Jap or the “Hunky” outside of your union, makes him a potential if not an actual scab, dangerous to the organized workers, to say nothing of his own as a worker. In spite of any supposedly inborn prejudice any of us may have for any race or nationality, we cannot escape from this point of view. Present industrial and social conditions in America force it upon us irresistibly. Hidebound craft union “aristocrats” and their blind leaders like Gompers may not see it; so much the worse for them. “Diplomatic” socialists like Berger may not see it; so much the worse for them. The WORKING CLASS, thanks to industrial and social development and I.W.W. propaganda, will ere long see the necessity of uniting AS A CLASS and sweeping all the reactionary rubbish of craft unionism into the Sea of Oblivion.

So we say to our correspondent.

Be of good cheer. The strong men of the working class will save the republic, and build a new and better society–Industrial Democracy–in its place.

The most widely read of I.W.W. newspapers, Solidarity was published by the Industrial Workers of the World from 1909 until 1917. First produced in New Castle, Pennsylvania, and born during the McKees Rocks strike, Solidarity later moved to Cleveland, Ohio until 1917 then spent its last months in Chicago. With a circulation of around 12,000 and a readership many times that, Solidarity was instrumental in defining the Wobbly world-view at the height of their influence in the working class. It was edited over its life by A.M. Stirton, H.A. Goff, Ben H. Williams, Ralph Chaplin who also provided much of the paper’s color, and others. Like nearly all the left press it fell victim to federal repression in 1917.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/solidarity-iww/1909-1910/v01n50-nov-26-1910-Solidarity.pdf