In this, the seventh letter to U.S. comrades, Liebknecht practically dares the censors with words of scorn toward the Hohenzollern Dynasty and a description of the nature and function of the press under Bismark’s regime. As well as the week’s war news.

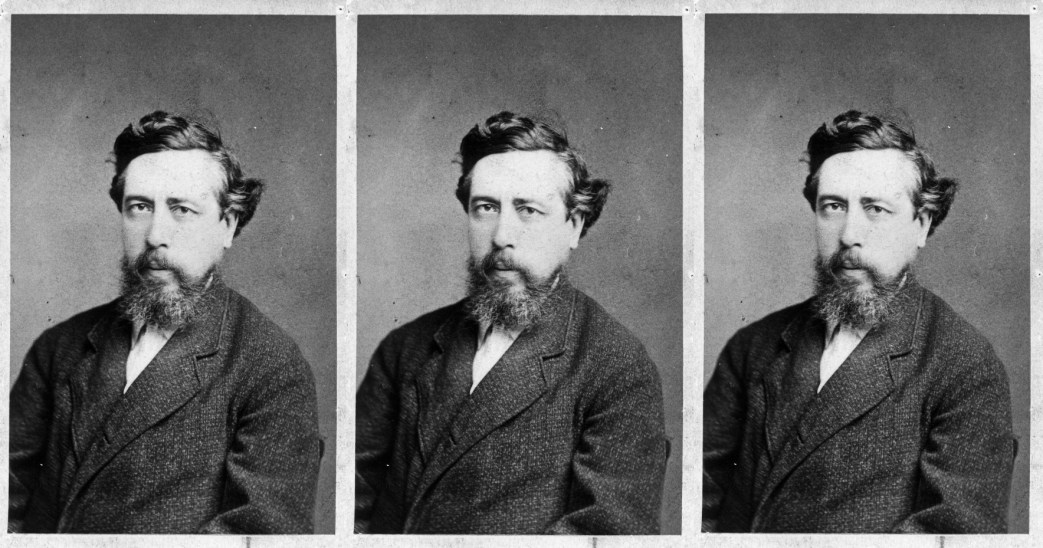

‘Letter from Leipzig, VII’ by Wilhelm Liebknecht from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 7 Nos. 27 & 28. March 4 & 11, 1871.

Leipzig, January 29, 1871

There is a story of an Italian surgeon, Villino by name, who, being short of customers, used to sally forth in the night under disguise, and to attack the solitary wanderers he met, stabbing the one with a dagger, knocking a second one down by a well planted blow which broke the bridge of his nose, fracturing with a bludgeon the arm of a third, and so on; after which performances he returned home, went to bed, and waited for the affrighted servants or relations, who would call him to cure the wounds and sores he had himself so providently created. The trade prospered, he soon became a renowned physician and a rich man, and as he sometimes cured the patients of his own workmanship for nothing, (when he had unfortunately hit upon a luckless individual that could not afford to pay) and as he went to mass regularly and made some donations to the church, he acquired the reputation of a saint. When I read the enthusiastic paenic commentaries and rhapsodies occasioned by King–pardon, Emperor William’s Imperial Manifesto,1 I am always vividly reminded of this Italian surgeon. A new era of power and glory opened to Germany through Hohenzollern Prussia. Germany delivered from the weight of French influence, through Hohenzollern Prussia. Divided Germany united through Hohenzollern Prussia. The pieces of Germany, which the greedy Welshmen2 once snatched from us, gloriously recovered through Hohenzollern Prussia. Well whether, or how far Hohenzollern Prussia has performed all these fine things, I will not discuss at present. In any case it is doubtful, since we are not at the end yet. But not doubtful is that Hohenzollern Prussia has done more than all the other German states and dynasties put together, to inflict upon poor Germany those very evils, from which we are told Hohenzollern Prussia has saved us now. From a long list, long as Don Giovanni’s, I will today only select two patriotic achievements of Hohenzollern Prussia. In the year 1689, when King Louis the Fourteenth sent his troop to capture Strassburg, the fairest jewel of Southwestern Germany, the Emperor of Germany, then hard pressed by the Turks, begged Frederick William, the Great Elector, and the real founder of the Hohenzollern Dynasty, to hurry to the relief of the menaced stronghold. What did Frederick William reply? “Strassburg does not belong to me–it is not my business to save it.” And so Strassburg became a French town for a century. French only by brute force, but since France was regenerated through the great Revolution, French in heart,3 like all Alsace and Lorraine. So much for fact No. 1. And now to fact. No. 2. One hundred and six years have elapsed. Hohenzollern Prussia has thrived well at the expense of the German Empire. In France monarchy is overthrown, the King beheaded for the sins of his ancestors. The monarchs of Europe, panic-stricken, have united against sansculotism–the Hohenzollern foremost. However the volcano was not to be extinguished, the coalition caught a cold in the mud of the Champagne (1792) and could not recover from it. The French Republic increased in strength, while the affairs of combined royalty looked rather hopeless. Might not the situation be turned to advantage? They had always a sharp eye on business, those Hohenzollerns or what amounts to the same people, with sharp eyes at their side. To betray one’s comrades is not nice. To enter into a treaty with the king-murdering Sansculottes is not handsome in a King proud of his right divine. But if something substantial is to be got from the king-murderers–non olet pecunia– money has no smell, said that Roman Emperor when pocketing the golden produce of a new levied tax on cloaks. The Hohenzollern scruples, if there existed any, were soon conquered, and secret negotiations opened with the French Republic. The offspring was the Treaty of Basel, by which Prussia delivered all of Germany across the Rhine to France, completely lamed Austria, and virtually destroyed the German Empire of course to the private profit of Hohenzollern Prussia.

And 75 years after she has knocked the German Empire to pieces, Hohenzollern Prussia sets it on its legs again–or to be more exact, on one of its legs, for the other leg. German Austria, is still cut off, and will not be fastened to the trunk by Hohenzollern Prussian surgery.

Is she not clever, this Hohenzollern Prussia. As clever as our Italian doctor was. Apropos, I did not finish the latter’s life story. He continued to prosper, was for his merits in the art of healing nominated honorary member of several scientific societies and universities, and would infallibly in the course of nature have advanced to a regular saintship, if he or the saints, just as you will take it had not been saved from Italy by an unexpected accident. The time had long passed when his professional practice required an artificial stimulus, sick people flocked to him from all parts of the world; but he had taken a liking to his nocturnal expeditions, and now and then he did for pleasure’s sake what he had not to do anymore for the sake of business. That proved his ruin. One night he caught a Tartar, in the person of a young, nimble apprentice; the intended patient turned the tables, knocked him down; the watchmen hurried to the place of the affray, by the light of their lamps our doctor was recognized, his dagger and his disguise were terrible witnesses against him, he was brought to prison, overwhelmed by the evidence, tried and sent to his last account, protesting to the end that as he had conscientiously repaired the injuries done by him, he was guilty of no crime, and that on the contrary, as those injuries had been the means of his improving medical science, he had served humanity well and ought to be rewarded instead of punished. Public opinion, I hardly need say, condemned him with the same fervor and unanimity it had before extolled him with, and almost raised a rebellion because he was only hanged, and not disemboweled, broken on the wheel inch by inch and finally quartered, in the patriarchial fashion of the good old times.

Public opinion, that flightly, light-headed shameless courtezan (volcanic Danton used a stronger, an unmentionably strong word), abjectly flattering those in luck, pitilessly cruel to the unfortunate, irresistible to the weak minded, despised by every man of character and brains, tyrant of the fools, and fool of the tyrants. Fool and worse. I think I wrote you already about the Guelph fund (Welfenfonds) property, from 700,000 to 800,000 (Prussian) thalers a year, which the Prussian government has confiscated. This sum is, according to Count Bismarck’s official declaration, made in the Reichstag or Diet (I don’t recollect now which), exclusively used for corrupting and bribing the press (in Germany and abroad) and for watching the enemies of the established order of things, that is, in plain language, for spies, mouchards, informers, agents, provocateurs and under whatever other names these worthies are known. Besides the Guelph fund we have the so-called Secret Fund for the same purposes, and under no public control, so that it is quite impossible to fix the amount spent. All in all, we shall not be far from the truth, if we estimate the sums thus expended for fabricating public opinion at a million thalers. Nor is this all. At Berlin there exists a Bureau of the Press, founded some thirty years ago, and in late years, grown to enormous dimensions, which Bureau consists of an irregular staff of a few dozen literary gentlemen, who have to treat the question of the day in the sense of the government. They are methodically instructed from above, receive the pieces of news which the government thinks fit to communicate to the public, and in such shape as they consider will produce the best effect, have to prepare feelers, have to praise the policy and the measures of the government, and the persons serving it, have to cry down its enemies, and other work like that.

II.

The notices and articles written by them are used in different ways. Some are published in two separate sheets, one lithographed and the other printed, the former (Zeidler’s correspondence) independent–that is, not acknowledged by the government, and therefore able to move unrestrictedly; the other–provincial correspondence official: that is, avowedly influenced or inspired by the government, but without being official. These two correspondences are sent at a small charge only nominal, or, if desired, gratis–to every newspaper in Berlin, in the Prussian provinces, and in the rest of Germany. Being of a specifically German and rather local character, they are not sent to foreign markets. Of far greater importance are the direct relations of the Press Bureau with the newspapers and newspaper writers not actually in the pay of the government. These relations are of two kinds. Firstly, the members of the staff provide the editors with articles, long and short, more or less liberal or conservative, conforming to the political shade of the respective papers, but always with the same tendency. The operation is performed very discreetly, and it is quite possible that an editor may not be aware of the true nature of his well informed Berlin correspondent,4 though such naïveté (ingeniousness) can in no case last long, since the cuckoo’s egg, so cunningly dropped in the nest, must in due time burst and disclose a young bird of a shape not to be mistaken. In this manner at least a hundred German newspapers and reviews, amongst them the larger ones almost without exception, are served; and if we add the numberless little papers that live upon plundering the big ones, I can say without exaggeration that the majority of German newspapers print what is written by members of the Berlin Press Bureau.

Secondly and this is perhaps the department of their activity most fruitful to the Prussian government–the members of the Press Bureau are, either as a body or as private individuals, in regular communication with the reporters and newspaper correspondents (special and non-special) crowded together at Berlin, furnish them with necessary materials, and make them the channels of Neo-Prussian Bismarckdom.

There are a few hundred newspaper correspondents, in Berlin, of all political opinions, writing in all languages and to all parts of the world, and of these few hundred not a dozen keep themselves free from contact with the Press Bureau. Even for a man of principle, who loathes the system, it is not easy to escape all contact; and as for foreigners, who are but imperfectly acquainted with our political affairs, and often with our language, too, they are hopelessly in the power of the Press Bureau.

To make it handier and cheaper for the foreign press, and especially for that in the English and French tongues, to which particular attention is paid, and to accommodate the less ambitious and wealthy papers that cannot well afford an “own correspondent,” one or two years ago English and French branch bureaus were fitted up; and it is no rare occurrence that exported public opinion is re-imported from Brussels, London, Paris (now Tours or Bordeaux), New York, etc., as genuine English, Belgian, French, American public opinion, and palmed off upon astonished Michel,5 who, and for good reasons, has no over-great respect for the home article, and feels highly flattered if he sees in what admiration his rulers are held by other nations.

These outlines will be sufficient to give an idea of the Prussian Press Bureau. Now think: this mighty engine, wielded by one will, producing public opinion in wholesale, and distributing it with the accuracy of clockwork over all quarters of the globe, not omitting the smallest provincial town in Germany; represent further to your mind the moral force which with some skill may be developed out of a million thalers a year;6 and you will not be surprised anymore by the tremendous outburst of world public opinion in favor of Bismarckdom, nor wonder at the otherwise miraculous precision of the international press monster concert which this public opinion has been performing for these last six months.

A bon mot, coined and circulated by the Prussian Press Bureau after the successes of 1866, is revived and applied to the present war: “The Prussian schoolmaster has gained the Prussian battles.” That is false modesty on the part of the coiners of bon mots and manufacturers of public opinion. The Prussian schoolmaster is a poor fellow, not fit physically to strike, because he is starving, and not fit intellectually to strike, because the famous school regulations, introduced and carried out by fanatic pietists of the Knak7 type, have deprived him of the faculty of thinking. Ah! if he had not been brought so low, if he was still what he was thirty and forty years ago, he might have found battles then, and gained them, too; but to be sure, not battles for the starvers of his body and the enslavers of his soul-battles which would have prevented Biarritz and the two fearful rivers of blood (1866 and 1870-1871), having their source there. No, it is not the Prussian schoolmaster–it is the Prussian Press Bureau that has gained Bismarck’s battles.

Its newest victory is no bloody one. The Bavarian Chamber has been subjected to such an overwhelming pressure of public opinion that the majority were frightened out of their wits and into acceptance of the Prussian treaty. So the “Empire” is complete–if we do not count the thirteen millions of Austrians for whom there is no room in this deteriorated and diminished edition of the old Confederacy which certainly was no model of perfection either. Well, be that as it may, this new victory is a fresh proof of the truth of what I said, I think, my first letter to you, that there is only one party in Germany which has not bent its neck under the yoke of Prussian despotism–SOCIAL DEMOCRACY. Undazzled by the glittering successes of the hour, the Social Democrats of Germany steadfastly follow the guiding star of Eternal Right, their numbers increasing as the dangers increase. Persecution, which destroys falsehood, strengthens truth; the hammer blows that shatter weak sandstone to pieces, redouble the tenacity of noble iron.

On the third of March the elections for the next Reichstag are to take place. Our party is already in the field; and though the loss of most of our spokesmen will be much felt, we enter the campaign with fair prospects. The two members which we had in the defunct Reichstag, Bebel and Liebknecht, are proposed as candidates in several districts each, and will doubtless be re-elected; but we hope to gain several seats.

P.S. Today the news has arrived of the capitulation of Paris and of the conclusion of an armistice for three weeks. Particulars are still wanting, but so much is certain that the capitulation as well as the armistice are the result of neutral mediation, which will most likely lead to peace. From the organs of the Prussian government, which have suddenly left off blustering and bragging, it may be perceived that Count Bismarck has convinced himself of the impossibility of overthrowing the French Republic. Whatever the conditions of the future peace will be, every point is of small moment compared with the one fact–the French Republic lives and will live. And its life is our victory.

NOTES

1. Apropos, I was not sufficiently accurate with regard to the date in my last letter. The Manifesto indeed bears the signature of the 17th, but it only fore shadowed the trying on of the Imperial crown and robe, which event took place on the following day. So mark January 18th.

2. The Frenchmen are called “Walsch,” which is pronounced nearly like the word “Ael h,” and has the sue origin: from Gali, Gaels. The name is applied to the Italians also, an Wallachia, Wallachin is of like root.

3. In an address of the Strassburg students to the students in 1867, it said: “We are French not since 4689, but since 1789.”

4. Woe to the paper which refuses, if it is under the thumb of the Prussian authorities. The licensing system has not been invented for nothing. I might mention staunch opposition papers that could save themselves from suppression only by accepting a contribution imposed by the Press Bureau.

5. The nickname under which the German people has personified itself.

6. Old Nick(olaus) of Prussia used to say: “A million of rubles spent in bribes saves a hundred millions spent on soldiers.”

7. A Berlin clergyman who considers it blasphemy to deny that the sun turns round the earth. He has written a treatise against the Copernican system, and is an intimate friend of the Minister of Public Culture, Von Muehler.

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

Access to PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-03-04/ed-1/seq-1/

Access to PDF 2: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-03-11/ed-1/seq-2/