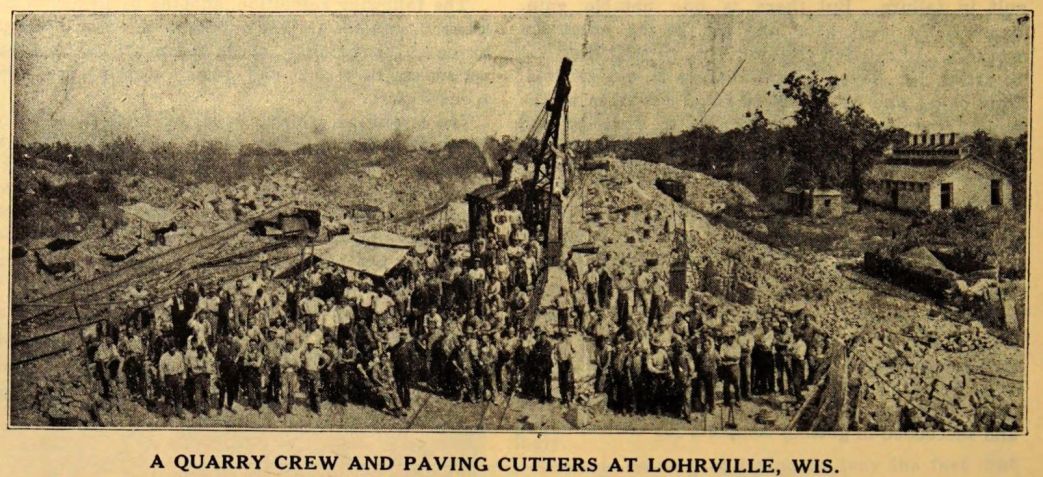

A fine workers-eye view of the conditions and organization in their industry.

‘The Developments of the Quarry Industry’ by S.J.H. from One Big Union Monthly. Vol. 3 No. 1. January, 1921.

(Editor’s Note—The following description of the quarry industry is a gem of simplicity and directness. It is written by a horny-handed paving cutter, by a man on the job. This explains how it is possible to convey so much information with so few words. We have repeatedly sounded a call for industrial articles. Here is one of them. The editor cannot sit down and write these. They can be written only by men on the job. This article may serve as a sample of what we want. Articles like this one are suitable for leaflets for the industry and will eventually serve as the backbone of an Industria] Union Handbook. Who is next with a write-up of his own industry?)

It took mankind a good while of traveling on the road called progress, before it became mighty enough to take up the struggle with the hardest kinds of rock that form the crust of mother earth.

It couldn’t be done, with any success, before some “ingenious inventor had found a method of tempering the steel to make it hard enough and tough enough to penetrate the hard rock.

There is no doubt that the first tools used were crude and simple, and without comparison with modern machinery in use today. But it made a foundation for improvement, a fact that is noticeable in any other industry.

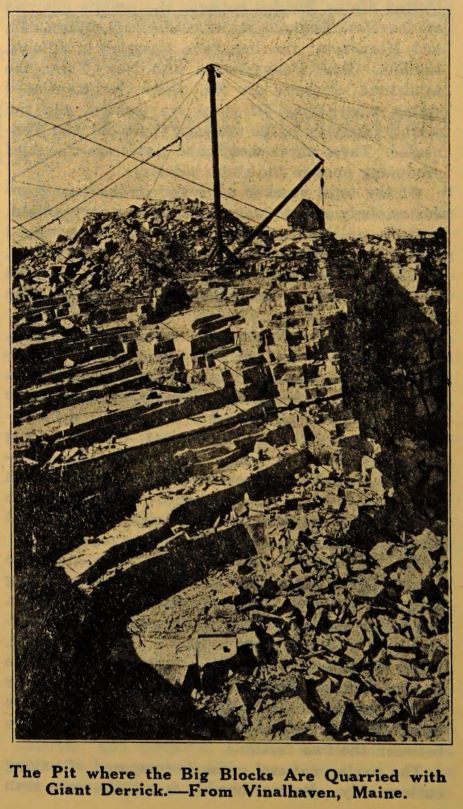

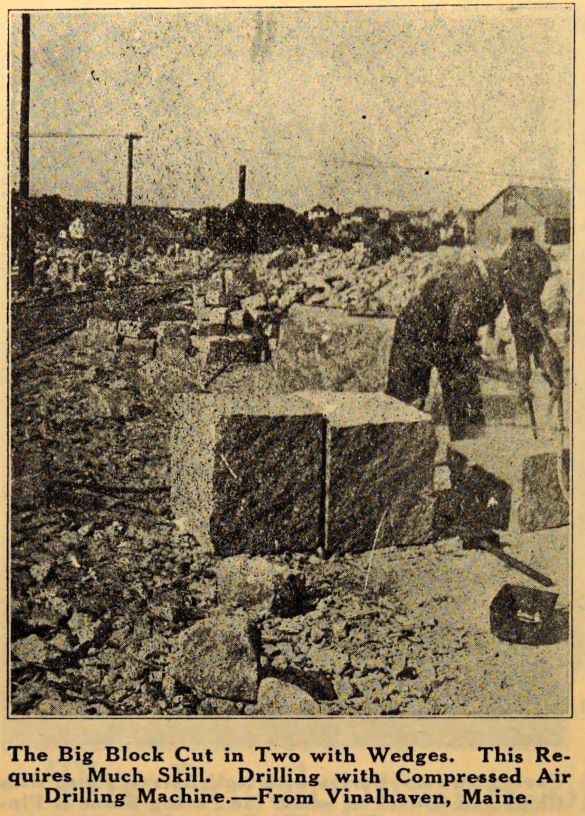

It would, perhaps, be very difficult to find out the exact date when stone was first quarried on this continent, but it can be traced as far back as 1817, when the first granite was quarried on the cape Ann, near Boston, Mass. The record of that place says “that a few men started to quarry out stone for a Boston building contractor.” (The above-mentioned place has for a long period of time held a leading place in granite production.) The progress seems to have been very slow up till the second half of the last century, when the invention of dynamite was made, which had a more effective power, especially where the stone is solid and “tight,” as we quarrymen term it, than black powder had. Since then, year by year, modern machinery has made its way into the industry with the same effect everywhere. A few men are now able to produce more than hundreds could do before, when everything was done by hand; as, for instance, both the drilling of blast holes and plug holes (holes for the splitting wedges), also hoisting the stones out of the pit, had to be done by manpower: alone in early days.

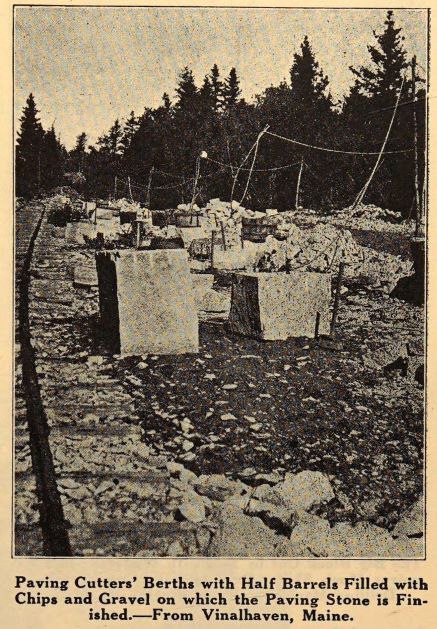

In those days it took a good deal of muscular training in order to develop a sure stroke on the drill. A miss would hazard the fellow turning the drill and sometimes prove fatal. Today, any man, without any previous experience, is able to accomplish more work with a drilling machine run by steam or compressed air, than a score of well experienced men could do before by using the hand hammer, and powerful electric or steam derricks will lift a stone weighing many tons out of pits sometimes several hundred feet deep, with an amazing speed. This also holds true concerning the trimming and finishing of parts of the product, with a few exceptions. Such exceptions are the paving block cutters, who do the trimming by hand, and the monument cutters, who use the hand hammer and the chisel, although not to such an extent as before. Now they have in use surface machines that will hammer down a big lump in no time. And then, instead of the slow process of crushing macadam by hand, there are stone crushers with a crushing capacity of hundreds of tons daily. The various kinds of rock that come under the jurisdiction of the quarry industry are mainly as follows: granite, marble, basalt, limestone and sandstone. Each of these is a kind by itself, differing very widely both in color, hardness and toughness, and in chemical composition, the latter being thoroughly explained by geologists, but of no vital importance to us quarryworkers. We are generally a lot more interested in the art of breaking or splitting the stone, than we are in its chemical contents.

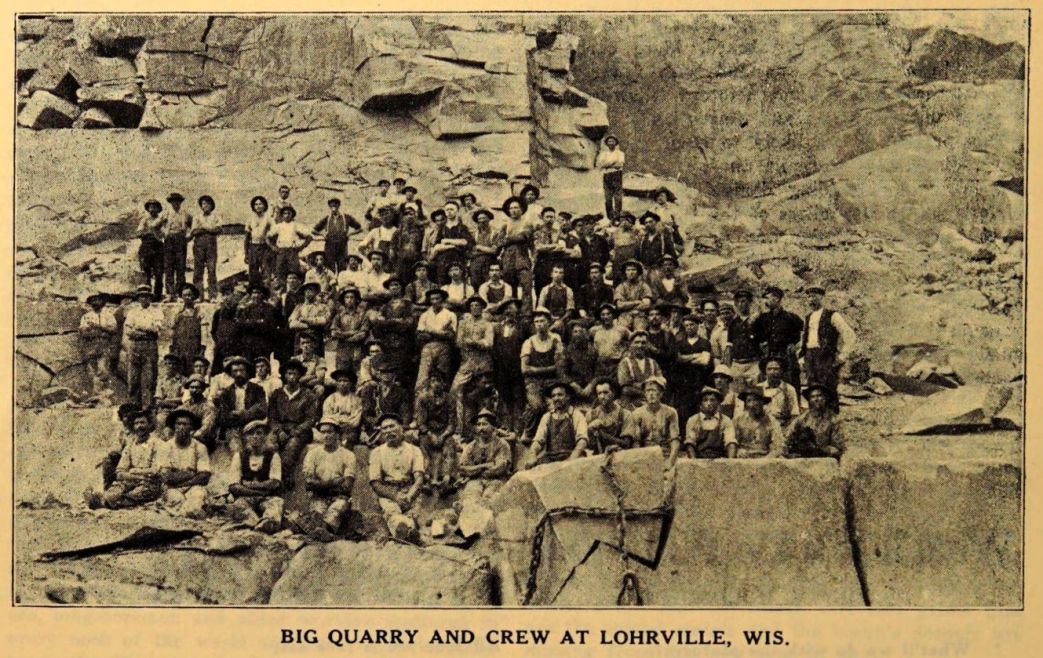

At the present time there are about one hundred thousand men engaged in the quarry industry of the United States, divided between the granite quarries of the New England states, California, Wisconsin, and Minnesota; the limestone quarries in Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, Pennsylvania and New York; the sandstone quarries in the three last-mentioned states, where most of them are located, and the marble quarries in the states of Vermont and Tennessee. These above-mentioned states are the chief producing ones in the stone industry.

Of the total number employed in the quarry industry, only about twenty per cent are organized. Not in one union, as one would have a very good reason to believe, but in four different craft unions, and I will now try to explain the working methods of the different unions and their relationship to one another.

The granite cutters’ organization, to begin with, is composed of workers that know the art of cutting monument and building stones out of granite. No one is admitted to membership before a three years’ term of apprenticeship is served. The number of apprentices is very limited, the idea being to protect the trade. As a general rule this organization has hitherto disavowed all connection with the other workers in the same industry and has never voiced any objections to finishing stones that have been quarried, sometimes, by strikebreakers.

The soft-stone cutters’ union is practically the same thing as the former, the only difference being that the material they work on is a little softer. Otherwise they work after practically the same designs and it has happened many a time in the past, when work was scarce, for instance within the granite cutters’ jurisdiction, that these went over to the soft stone and vice versa. This often gave cause for hot disputes and sometimes open warfare between the two factions.

The paving cutters’ union is composed of paving cutters only. Its membership is a little more than three thousand, and this is perhaps the only craft union that can boast of having every man that works in the trade in the United States and Canada within its fold. As it is a perfectly organized craft, one would have very good reason to believe that the organization could enforce any demand it saw fit to put before the bosses, but that is not so, owing to the fact that the paving cutters only form one part of the many, working in, or around a big quarry. In the case that the paving cutters go out on strike, the others remain at work and the boss gets along nicely without them for a while. And generally it doesn’t take very long before they are starved into submission.

And, finally then, concerning the last of the four crafts, the Quarrymen’s International Union, it is to be noted that it is composed of workers that could not claim membership in any of the former, but are considered to be in possession of some skill of one kind or another, such as toolsharpeners, drillers, derrick men and mechanics. In general character this union does not differ very much from any of the former. It is, like the rest of them, affiliated with the American Federation of Labor.

Now remains the so-called unskilled labor, which includes the block handlers, crushermen and those doing the “stripping” and other forms of labor around the quarry. They are unorganized even at such places where all the other unions are established, the reason being that they are not admitted in any of them, and, consequently, they have got to remain outside whether they like it or not.

The working conditions in general are not ideal, although an eight-hour day is prevailing where the unions are in control. In the non-union quarries, at least the majority of them, the bosses work their men from nine to ten hours a day, which is by far too long at this extremely hard work.

In regards to wages the quarry workers have been lagging far behind others, especially during and after the war period. There are two reasons for this. First, the majority of the organized workers were bound by contracts, some of them in force for a period of not less than five years, which proved to be one of the most foolish things that a group of workingmen could do. This was proved more clearly than ever before through the unusual advance in prices of the chief necessities of life. But as time went on and prices were soaring higher and higher, they soon found out that there was only two alternatives left to them, either to work according to their obligation and starve to death in the meantime, or scrap the sacred contracts and live. The men naturally chose the latter. Secondly, the war had a depressing effect on the industry, and many men left the quarries or, were forced to leave and seek employment in more essential industries. But in this last year conditions have improved a little in regards to wages. This is owing to the great demand for all kinds of quarry products and the old quarry men’s gradual return to their former jobs.

It is hard to get the exact amount of wages received in all branches of the quarry industry, due to the fact that there are many that work on the basis of piece work, at least among the paving cutters. This is a system that should be utterly condemned, because it destroys the spirit of solidarity.

The granite cutters last spring went out on a strike and secured a minimum wage of one dollar per hour. The paving cutters certainly run far below that mark, taken on an average, and the other workers in the industry are getting from four to six dollars per day, probably some more and some a little less in various places.

There is no doubt, if they had been properly organized, they could have had more. But as conditions stand today, with a small percentage organized in craft unions and the great mass of the quarry workers unorganized, the result must be accordingly.

There is no need of trying to deny the fact that the different unions have tried to better their conditions. They have, indeed, fought many fights in the past, but they have fought according to craft union tactics, which in most cases is bound to result in failure. But there is one notable gain, namely, the eight-hour day for all the organized workers. In the Red Granite, Wis., district they had to strike for eleven months before it was secured. This being one of the most notable strikes in the quarry industry, both in regards to duration and the number of men involved, and the attempt of the bosses to railroad some of the strikers, which did not prove successful.

In the year of 1916, the unorganized men of the above-mentioned district struck, when their demand for higher wages was refused. The skilled workers were forced to idleness, but were otherwise most willing to scab on the unorganized if given a chance. During that strike, in spite of only a few days’ duration, a local of the Quarry Workers’ Industrial Union of I.W.W. came into existence, and after a few weeks it had a membership of nearly four hundred and succeeded in getting complete job control in two quarries. As a consequence the working conditions improved considerably for all men concerned. But then came the United States’ entry into the world war with its depressive effect on the quarry industry and the men were forced to leave and seek employment in more essential industries. This, along with the suppressive campaign by the federal authorities, caused the death of the first local of the Quarry Workers’ Industrial Union of the I.W.W. It is true the local was short-lived as such, but there can be no destruction of ideas, and the men that composed the above local will spread the One Big Union doctrine on all continents, and the second one will be born for sure, because the necessity demands it, and it can’t be avoided. The sentiment in favor of the One Big Union idea is growing stronger for every day in all branches of the quarry industry, and a time will come when the toilers of the quarries and sheds will join hands with the toilers of forests, fields and factories, with all who toil; and establish the industrial commonwealth of the workers.

The following resolution, adopted by Branch Vinalhaven, Maine, in 1914, before the war created havoc in this industry, sheds additional light on the conditions the stone and quarry workers are confronted with.

The resolution, which is reprinted from the Quarry Workers’ Journal, after being carried by Branch Vinalhaven of the Paving Cutters, one of the biggest in the country, was put to a referendum vote among the paving cutters and lacked only 6 votes of a majority, showing that already six years age sentiment for industrial unionism was strong among these workers.

Now that the war is over and the industry is picking up again, the seeds thus sown should be taken care of and the question of organizing One Big Union of this industry should be taken up again.

RESOLUTION

To Branch Vinalhaven of the Paving Cutters’ Union of the United States and Canada:

Brothers and Fellow Workers:—

We, the undersigned, members in good standing of Branch Vinalhaven, Paving Cutters’ Union of the U.S. and Canada, herewith wish to introduce the following resolution to our Branch, to wit:—

Resolved, by Branch Vinalhaven of the Paving Cutters’ Union of the U.S. and Canada,…That we begin a systematic agitation with the end in view of merging into one single industrial union all Branches of the Paving Cutters’ Union of the United States and Canada, the Granite Cutters’ International Association of America, the Quarry Workers’ International Union of North America, and of all other Unions in the stone and quarrying industry, such as soft stone cutters, marble cutters, etc., thereafter adopting the name of the Stone and Quarry Workers’ Industrial Union, having only one local Union or Branch in each establishment.

In support of the above resolution we wish to present the following reasons:

I. The present, above-mentioned Unions are all built on craft or trade lines, the boundaries between them being the difference in the tools we use. This sort of craft or trade Unionism has its historic explanation in the fact that production was until recent times organized and carried on along craft and trade lines. But the age of crafts and trades is about gone. We are now living in the age of industrialism. The workers have nearly all been turned into industrial wage workers, and production and distribution is organized, on industrial lines. The owners of the natural resources and the other means of production and distribution have also long ago abandoned craft organizations. They are now arrayed against us on industrial lines in the shape of syndicates and trusts. In our struggle for existence we, the workers, are thus hampered by our old fashioned forms of organization. We are unable to meet our organized employers on equal ground for lack of industrial solidarity.

All over the world the workers are now remodeling their organizations on industrial lines. The time is ripe for us to do the same, the sooner the better.

Having thus stated the general principle upon which we demand the change embodied in our resolution, we wish to add a few more reasons why such a change is desirable and imperative.

II. Our present forms of organization are very expensive and wasteful. A large percentage of our hard-earned money is being frittered away by maintaining four national offices with rent and other expenses; four national committees with their expense accounts; four national conventions with heavy traveling and other expenses; several separate official organs with printers’ bills; several sets of organizers, local officers and stewards with their expense accounts; and, finally, several sets of local meetings with hall rents and incidental expenses.

By merging into one Industrial Union of Stone and Quarry Workers, with common administration and finances, we could bring these running or administration expenses, now amounting to many thousands in the aggregate every year, down to nearly one-third of the present sum. The money thus saved would be available for the education of our membership in the principles and tactics of an up-to-date labor organization.

III. Furthermore, divided as we are on craft lines, we lack the power and the resources that we would have by merging and uniting. We now make separate agreements and contracts which are allowed to tie us down for a number of years and which not infrequently put us at cross purposes with one another, when in conflict with the employers. This state of affairs largely accounts for the fact that our average yearly earnings fail to keep pace with the constantly rising cost of living, all the while we are being speeded up to the very limit of human ‘endurance and succumbing prematurely to the numerous dangers, ailments and diseases peculiar to our industry.

On the other hand, by presenting one solid and united industrial front to our exploiters by means of One Big Union, we would cause this state of affairs to be changed and be able to dictate, through our organized power, the wages and the working conditions in keeping with our own wishes and our own welfare.

IV. Finally, we should not fail to take notice of the fact that throughout the world the light is breaking upon the workers that we stand on the verge of the most stupendous transformation of the economic structure of society. The private ownership of the means of production and distribution is doomed by the force of natural laws. It is only a question of time when the old economic structure which we call the capitalist system shall collapse, depending upon the efforts put forth by the workers through their Unions. Production and distribution will then be taken over by the workers themselves through their Unions. Millions of wage workers are already organized all over the world with this avowed purpose in view. It is a new order of things forcing itself upon us. We must not and we cannot avoid this historic mission of the working class, nor should we shirk the responsibility devolving upon us.

But, naturally, we cannot, in the final issue, take over and run the industries, unless we are organized on corresponding lines. Our present craft Unions will not do for the purpose. The One Big Industrial Union we aim at must unite, in one organized body, every man working in the industry.

We stone and quarry workers at present fall short of this mark.

Let us, therefore, speedily merge into One Big Industrial Union, simple and inexpensive to administrate, strong and easily maneuvered for fight, and prepare to accept the glorious and important role which social evolution has destined for us, namely, to take over and run the industries, in the interest of the whole people instead of for the profit of a few rich individuals.

Thus we shall realize the ever more popular demand for “the full product of our toil’? and take our proper place in the march forward to a higher social order—a new society.

In order to carry into effect our demands for a reorganization and a re-alignment of our industry on these lines, we, the undersigned, make the following motions:

1. Moved, that Branch Vinalhaven send a copy of the above resolution and our reason therefor, as well as of this and the following motions, to our National Union office for publication in our Journal, with the request that it be republished in full by the official organs of our brother organizations.

2. Moved, that a similar copy be sent to the Branches of the Granite Cutters’ International Association of America and the Quarry Workers’ International Union of North America here in Vinalhaven for their consideration and as a suggestion to cause similar action to be taken on the part of their Unions throughout the country.

3. Moved, that our delegate to our next national convention be instructed to introduce the above resolution to the convention and to make motions appropriate for carrying the same into effect.

4. Moved, that the columns of our official organ be opened for a thorough discussion of this important matter.

5. Moved, that we direct an earnest appeal to the Stone and Quarry Workers all over this continent to take this matter up at the earliest possible date in order to secure thorough consideration of same, as well as speedy and uniform action.

Adopted and carried by Branch Vinalhaven, Paving Cutters’ Union of the U. S. and Canada.

Vinalhaven, Me., 1914.

One Big Union Monthly was a magazine published in Chicago by the General Executive Board of the Industrial Workers of the World from 1919 until 1938, with a break from February, 1921 until September, 1926 when Industrial Pioneer was produced. OBU was a large format, magazine publication with heavy use of images, cartoons and photos. OBU carried news, analysis, poetry, and art as well as I.W.W. local and national reports. OBU was also Mary E. Marcy’s writing platform after the suppression of International Socialist Review., she had joined the I.W.W. in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/one-big-union-monthly_1921-01_3_1/one-big-union-monthly_1921-01_3_1.pdf