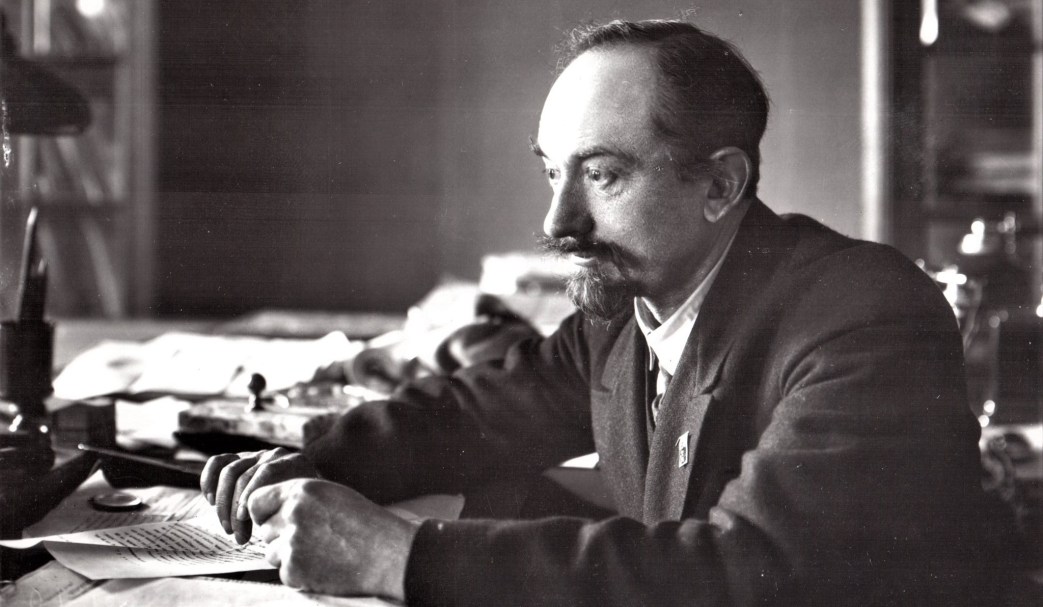

In clear, simple language the Commissar of Foreign Affairs, the never-to-be-replaced Georgy Chicherin, gives a masterclass on what revolutionary diplomacy and proletarian foreign policy is.

‘The International Policies of the Two Internationals’ by Georgy Chicherin from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 6. October, 1919.

The international policies of the Yellow and the Communist Internationals have nothing in common, in fact they are totally opposed to each other. The international policy of the Communist International is as clear and definite as the Bern-Lucerne international is vacillating and unprincipled. The policy of the latter consists in partial amendments to the foreign policy of the dominating great powers. It is a policy of sticking small patches on the Imperialist coat of the Entente. We find a long list of such petty patches at Berne and Lucerne, in the declaration of the commissions elected at those congresses, and in the parliamentary activity of parties that are in close touch with the above commissions. Various questions and points of official diplomacy are discussed: about Sleswig, Memel, Tyrol, Syris, Georgia, a series of other newly formed republics, and on all those questions and points the Yellow International either upholds the decision of the great powers or offers some partial amendments. The purpose of these amendments is to make the political system of the great powers somewhat less hateful, and to mitigate the too obviously rapacious character of that system. The League of Nations is glorified, only its partial improvement is demanded. Various amendments are proposed to the Versailles treaty, but nothing is said with regard to the cession of the Saar mines and contribution to be paid by Germany. A wish is expressed to allow Germany to retain her colonies. The fundamental idea is the belief in the possibility of attaining all the necessary changes by means of negotiations with governments The politicians of the Yellow International, like flunkeys, hover around official diplomacy to clean its dress and give it a more decent appearance. In its essence the international policy of the Yellow International means only subservience to the diplomatic system of the great powers. That policy only criticises details, leaving the impression that the present governments are capable conducting a foreign policy in the interests of the masses. This activity of the Yellow International can in fact only strengthen the official political system, increase its authority in the eyes of the masses, and postpone the moment of its inevitable bankruptcy.

The foreign policy of the Yellow International is essentially a direct and logical continuation of, the foreign policy of the Second International as it began to shape itself before the war. The programme on the solution of the Eastern question by the Second International at Basle in 1912, when war threatened Europe, was regarded as an attempt of the international to carry its positive programme on foreign affairs.

The socialist press of various countries pointed with great pride to the Basle resolutions, which were supposed to open a new chapter in the history of the socialist movement, namely the beginning of the positive work of the International in the sphere of diplomacy. Unfortunately, the question of its positive work in the sphere of foreign politics has hardly been dealt with at all. Personally, I can recall only one article by Rosa Luxemburg on the foreign policy of Jaurès, which dealt with it only incidentally. It was taken for granted that foreign policy was only a continuation of home policy, that it was inseparable from the latter and the question of distinguishing one from the other was never touched. It was therefore considered very desirable to elucidate the positive tasks of the socialist parties in foreign politics. In various countries that task was undertaken by parliamentary statesmen of the type of Jaurès. The Yellow International at Berne and Lucerne is only continuing that tradition,–wholly in keeping with the commonplace views held in this respect during the last years before the war–by worrying over the fair solution of the questions of Georgia Armenia, Fiume, etc., thus rendering invaluable services to world reaction.

There was an entirely different line in home politics. Not one socialist section could doubt that it had a precise and definite programme in the domain of home politics within the limits of the existing order. During the last period of the existence of the Second International, parliamentary activity was not of a purely declarative character, for every tendency in the socialist movement and every individual socialist–whatever his opinion of the importance which various victories achieved in parliaments might have on the course of the proletarian struggle–tries to contribute to those victory in a direct way, just as the labour movement was striving to obtain them by economic struggle, outside the walls of parliament. The minimum programme was understood in different ways by the many socialist tendencies, but none of them could refuse to fight for the immediate realisation of any part of the minimum programme. The every day political and economic struggle consisted in continuously wringing concessions from the governing classes, i.e., the struggle consisted in the execution of the positive programme within the limits of the existing order.

The foreign policy was essentially different. Home politics is a ground upon which labour and capital, people and government, working class and ruling class, are brought face to face. It is precisely here that the ruling classes were compelled by political struggle to make one concession after another, it is here that socialists carried out their positive programme within the limits of the existing order. Foreign politics is the relation of one state to other states, i.e., to partners or competitors in world plunder, the relation between strong states and weak ones, and finally the attitude to colonies, which are mere objects of plunder. Two elements can be distinguished in foreign politics; first, the system of political combinations, alliances and hostilities; i.e., means for the attainment of ulterior objects of foreign policy; secondly, those very objects which can be reduced to two categories–defensive and offensive. One aim in the foreign policy of all governments always consisted in the defense of its possessions. It was necessary at any moment–by means of international combinations–to be so strong that a rapacious enemy who desired to snatch from that country either an integral part of it or some one of its possessions could not do it without a fight, owing to the opposing forces of a diplomatic coalition. Diplomacy was one of the weapons of national defense, it added and complemented the troops guarding the frontiers, fleets guarding the shores, fortresses and defending dangerous points. The second group of aims of foreign policy consists of annexations, over which the capitalist governments fall out, though they may have previously helped each other in acquiring them.

The attitude of the Second International to national defense was, as is well known, never thoroughly analysed. This still remains an open question. The Stuttgart and Copenhagen resolutions contain the most irreconcilable contradictions, which were so dramatically revealed during the war. But the revolutionary wing of the Second International has to a certain extent shown its hostile attitude to so-called national defense, and definitely declared against voting for war credits. The socialists, by defending the capitalist state in matters of military defense, would thereby uphold the whole system of the dominion of the class enemy; and similarly if they declared their solidarity with the foreign policy of their governments, even in so far as its object was purely defensive, they would be doing the same. There is no difference between the defense of the country by armed force or by diplomacy. During the war the French social traitors supported martial law in France as well as in Russia. The whitewashing of Tzarism in England was part and parcel of the defense of the country as understood by social traitors. Other parts were speeches at meetings in support of the government coalition, the prevention of strikes, the abandonment of trade union privileges.

The offensive foreign policy of capitalist governments were from beginning to end a scheme of robbery. Such actions, at first sight contradicted that definition, such as intervention on behalf of persecuted Armenians, the intercession of Wilhelm II. for the Boers, the Tzarist policy in the Near East during its so-called liberation period, were in fact moves in the same game of robbery or else cleverly concealed attempts to advance in that direction. The socialist parties that deserve that name should treat that political system of robbery with the same uncompromising hostility as the Stuttgart Congress treated all colonial policies without exception. We can say that colonial policy is the most clearly defined and typical example of capitalist foreign policy. The revolutionary wing of the International, under these circumstances, could not have a positive policy on foreign politics within the limits of existing state relations, it could have only a negative programme. i.e., of putting obstacles in the way of foreign policy of the existing governments. The tasks of the revolutionary wing of the International in matters of foreign policy were to fight against colonial policy, against armaments, against war, against all open and secret annexations.

These tasks were purely negative. Equally negative was the programme of solving the Eastern question, as worked out at the Basle Congress. It consisted in proposing a federation of all the Balkan nations in contradistinction to all the combinations proposed by the existing governments to solve that question. That Balkan Federation could only be formed by fighting both the great powers and the Balkan governments as they then existed. This was more a component part of the revolutionary programme for the Balkan nations themselves than a programme of foreign policy. It was called foreign policy by mistake. The commonly accepted notion, that by adopting the Basle resolutions, socialist parties had started positive work in the field of foreign policy, is also due to a complete misunderstanding. There was no such positive work in the Basle resolutions; they only contained watchwords for the Balkan nations with which to fight their own governments. The instructions given at Basle to socialist parties of other countries bore a purely negative character, and merely showed the necessity of combatting the foreign policy of their own governments. The Basle resolutions only lay it down that the revolutionary wing of the International could have no positive programme at all on foreign policy, that it could only follow a negative policy, making its business the obstruction of the policy of capitalist governments.

The so-called home politics is the field in which labour and capital stand face to face. The positive programme of the socialist parties in this field consists in the following: The working class, by means of a political and economic struggle force the governing class to yield one position after another. International politics is the field where capitalist governments are facing each other and the oppressed countries. Therefore, as I have said, the revolutionary wing of the socialist movement could only adopt a negative programme in international politics; i.e., to prevent the combinations and robberies of capitalist governments. But a subject country or a colony can fight and revolt against its oppressors–the capitalist governments–just as the workers do in their own countries. The task of the socialist movement in any given country consists therefore in preventing its government from crushing the revolting oppressed country; a purely negative task, as pointed out before. The socialist movement, however, has another task to perform; to render not only negative but also positive assistance to the revolting country. The working class has thus its own proletarian foreign policy. In this case it consists in the rendering of immediate aid to the victims of the capitalist government. Such activity on the part of the working class of any country is not limited to the instance of rebellion quoted above, but extends to all the struggles in its own country and abroad between oppressed bodies of men and the capitalist governments; generally speaking, between oppressed and oppressors. We can say that proletarian foreign policy expressed the whole activity of the International. The activity of the International as such was in itself proletarian international policy, distinct from the government foreign policy and wholly opposed to it. In the field of foreign politics the task of the working class–in so far as it was revolutionary–consisted in opposing its own proletarian international policy, to the foreign policy of the government, i.e., to wage a class war on an international scale.

In home politics the positive programme was being carried out by snatching from the government one advantage after another. Could not the working class act similarly in foreign politics in each individual case by not only preventing its government from doing certain things; i.e., fulfilling a negative task, but also by forcing it to fulfill the positive aims of the proletariat, thus carrying out the positive programme of foreign policy within the limits of the existing order? If the working class can help some revolting oppressed territory, why could it not compel its own government to help that territory? That was precisely the sophistry which used to lead the bourgeoisie reformers of the labour movement astray. In many cases the governments not only willingly fulfilled such wishes of the reformers, but even undertook the initiative in these matters themselves. The policy of the great powers in Turkey consisted in the alleged attempt to help the oppressed against the oppressors. It is enough to mention this instance to realise that the revolutionary thinking proletariat could help any oppressed body of men only in one way: By helping it directly without any intermediaries. Any interference on the part of the rapacious capitalist governments in any fight of the oppressed against the oppressors in any part of the world would only mean that a new object will be drawn into the sphere of their rapacious combinations. If the revolting nation could attain its object by its own forces it would undoubtedly be the gainer thereby, but if any presumably good results are due to the good offices of this or that rapacious capitalist power, even under the pressure of socialists, then we may be sure that that power, being itself the instrument of fulfillment of a presumably liberating task, had the possibility of fulfilling it in accordance with the demands of its rapacious policy. World relations are so mixed up, and the predatory interests of each capitalist power are so interlaced with the political relations of the whole world that each individual local task is bound to be fulfilled by each power in accordance with its world policy. The attempts made by socialists to render assistance to any oppressed group through the medium of a capitalist government, gave the latter a possibility of making new combinations such as would favour their world policy of plunder and to cheat the masses by their support.

The fact that any change of the political frontiers would open up to the imperialist governments of the world a wide vista of realising their piratical combinations, the revolutionary wing of the socialist movement was quite right in considering its duty to be to fight within the existing political frontiers, not to strive for any alteration of the latter. It is from this standpoint that it dealt with the questions of Poland, Alsace Lorraine, and other irredentist territories. In this question the revolutionary wing fully realised the inadmissibility of a positive programme in the field of foreign politics in the existing order. Unfortunately its attitude to foreign politics in general was never formulated in an exhaustive and systematic way. It is the absence of clearness in the formulation of this question that gave the opportunity to a considerable part of the politicians of the socialist movement to busy themselves in foreign politics in a manner highly prejudicial to the revolutionary proletariat. Before the conclusion of the Franco-British alliance, Jaurès constantly agitated in its favour, regarding such pseudo-democratic alliance as a valuable counterbalance against the reactionary alliance with Tzarism. During the general scramble over Macedonia, when France, England and Italy put forward their schemes of reforms for that country in opposition to the Austro-Russian programme, some naïve socialists supported by Germany imagined that this political combination was an extremely important democratic gain–the beginning of the union of democratic nations against the reactionary nations. The arguments of social traitors during the war were essentially the same as those of socialists at the period of the Macedonian reform scheme. The social traitors kept up in their entirety the traditions of the Second International. Similarly in Germany Bernstein was agitating in favour of an alliance with Britain, following the old traditions of the German free-thinking party Jaurès went even further: in a series of brilliant speeches, made during his parliamentary career, he constantly urged the French government to open up a new era of foreign policy, based on justice, loyalty, progress, etc. We can say that it is precisely in the domain of foreign politics that the complete utopia of petty bourgeois opportunism in the socialist movement is revealed. It is revealed as a helpmate and tool of the government policy in cheating the masses and in following piratical aims’ under noble pretexts. The governments of the most advanced capitalist countries have for a long-time past been anxious to strengthen their pre dominance in their countries by considerable concession to their own masses in order to have, a free hand in their world robbery, which was for the oligarchy its chief source of profit. Sentimental dreamers like Jaurès, shortsighted and overconfident, were precisely the men they wanted. By their eloquence and sincere conviction they were helping their governments to acquire the support of the masses and to spread the idea that a democratic world policy was possible. They prepared the “civil peace” in the great war.

The Second International unfortunately did not go far enough. It only gave a correct definition to its purely negative task with regard to colonial policy, but not logical enough to apply it to the foreign policy as a whole during the present régime. This lack of clearness had the effect of enabling the governments to utilise the proletarian organisations in the interests of their war policy. The proletariat must never have a programme of active participation in the policies of the existing governments. The proletariat, however, did not realise it sufficiently clear and as a consequence considerable socialist groups demanded the internationalisation of the Dardanelles and other international reforms under the present régime. Asquith, who for the first time in the name of the British government, in his Dublin speech (autumn, 1914) demanded the creation of the League of Nations, was merely borrowing this slogan from pacifists and socialists.

When Bernstein and others were advocating the alliance with the so-called democratic governments, they were not only following the traditions of the free-thinkers, but also based themselves on the authority of Marx, who gave the socialists of his day most definite directions in matters of foreign politics, namely, alliance with the bourgeois liberal governments against Nicholas I. The historic conditions in those days, however, were different. In the middle of the nineteenth century bourgeois society was not universally freed from the bonds of feudalism and despotism, and the creation of international conditions favourable to the free development of the bourgeois governments was a task in which the working class was also interested. The time had then arrived for the creation of national states, a condition precedent for the normal development of capitalist relations. In those days Marx was quite right in putting before the socialists positive tasks in foreign politics. Such a task was the fight against the international dictatorship of the despotic Nicholas I., although at the time of the creation of national states the revolutionary proletariat could not act as an ally of the reactionary monarchist governments, which undertook this task. Nevertheless, the task itself, considered in the abstract, appeared progressive. The next historic period passed under different conditions, when the bourgeoisie was complete masters of the state, and the remnants of the former regime became merc tools of triumphant capitalism. In home and foreign politics the remnants of the outwardly democratic forms were used only as a screen for the mismanagement of the capitalist oligarchy. There were no longer any progressive positive tasks in which the proletariat could be interested. In the last period of world history, international politics were exclusively a series of combinations made by rapacious capitalist governments. The revolutionary proletariat must hold itself aloof from all these combinations. It must do its utmost to help the victims of capitalist robbers, to help the oppressed classes and oppressed groups, and must refuse to co-operate with the diplomatic combinations of capitalist governments.

The situation changes entirely with the appearance of the workers and peasants’ Soviet governments. For the first time after a long interval the revolutionary proletariat can again have positive aims in the field of international foreign politics. For the first time governments have appeared in whose support the international revolutionary proletariat is vitally interested. These governments put themselves in the centre of the whole world battle between the oppressed countries and groups and their oppressors. The revolutionary proletarian parties and groups of all countries are confronted with the task of fighting for the existence and the strengthening of the international status of the revolutionary Soviet governments. This new programme of foreign policy can only be adopted by those parties and groups which base themselves on the revolutionary Soviet system. Positive international politics can exist only for the groups that follow the Third International. The Yellow Bern-Lucerne International can only adopt towards the Soviet governments the timid attitude of non-intervention, it can only continue to follow its cringing pseudo-democratic tradition of the reformists of the Second International, to pretend to criticise the reactionary capitalist governments, but in reality it thereby strengthens their position and helps them to hold out and cheat the masses.

The revolutionary Soviet governments are in a somewhat different position from that of the revolutionary parties. As de facto governments surrounded by other governments, they have to enter into certain relations with the latter and this circumstance imposes on them certain obligations, with which we have to reckon. A Commissary for Foreign Affairs, contributing to the organ of the Third International, must reckon with the position of his government, which is no longer a revolutionary party without a chance of being in power. At the same time, however, the revolutionary Soviet government by its character and aims is totally opposed to the capitalist governments and can in no way take part in the rapacious combinations. Its task is, therefore, to live or try to live in peace with all the governments, and carefully avoid all participation in any coalitions or combinations that serve to satisfy imperialist appetites. And the Soviet governments, being equally opposed to the capitalist governments, are natural allies by force of circumstances, but this can only be in a defensive sense, as they none of them have anything to do with any aggressive policy. State defense, which is the cornerstone of the international capitalist policy, is equally the first consideration of the Soviet foreign policy. With regard to the “defense of the country,” if the country is a capitalist state, the revolutionary proletariat must not take any active part in it. On the other hand the defense of the workers’ and peasants’ Soviet government is a matter in which the proletariat is primarily and vitally interested. But just as the defense of capitalist states is not only carried out by soldiers and guns, but in no less degree by diplomacy which strives to prevent the formation of hostile coalitions, against which guns and soldiers may be powerless–so in the defense of the Soviet government international political relations play very important part, the object of diplomacy being the same; i.e., to prevent the formation of hostile coalitions. The object of international combinations is to obviate the danger of attack, and they also impose certain definite obligations. At the present historic moment, when forward their schemes of reforms for the country in the Soviet governments are surrounded by enemies on all sides, when they are beset with dangers and difficulties which threaten their very existence, they have to be very careful and reckon with the requirements of foreign policy. Soviet diplomacy has a purely defensive part to perform, but that part is highly responsible. Thus when we speak of the positive tasks of the Third International we cannot identify the communist parties with the Soviet governments where these parties predominate.

The Soviet governments not only take no part in any combinations of the imperialist governments but follow a diametrically opposite policy to theirs with regard to oppressed countries and bodies of workers, in particular to colonial nations and countries. The Soviet governments, recognise the rights of these countries in general, and their rights to self-determination in particular. The very restrictions themselves, which are imposed on the Soviet governments, owing to their relations with other powers vary, and depend on political circumstances. In the first month of its existence, before the Brest treaty, the Russian Soviet Government followed a strongly declarative line, in the spirit of the world proletarian revolution. It is impossible to estimate the immense impression it created in those days. That impression left a permanent mark in the world labour movement and determined once and for all the attitude of the latter to the Soviet governments.

However hampered the present Soviet governments may be in their activity, the left wing of the labour movement of all countries will always regard them as the central feature of their positive international policy. The socialist parties at the time of the Second International followed their international policy outside the international politics of state respective of their relations.

The Third International has its international policy of common aims and actions in all parts of the world. In the sphere of its international state relations its positive programme centres on the international position of the Soviet governments, on their political union, on their support by all who share their ideal. The very existence of the Soviet governments, the foundation of new Soviet republics, which took place before now and will, we expect, take place in the future, all this entirely changes the attitude of the revolutionary wing of the world labour movement to all the current questions, big and small of official diplomacy. On the period of the Second International the revolutionary wing of the socialist movement could only adopt a purely negative attitude toward imperialist robbery on all the questions of international politics, such as the Syrian, Armenian, and others. At the present time the Third International opposes the definitive aims of the Soviet organisations and the prospect of an immediate liberation from the imperialist yoke to the robbery. History has set immediate revolutionary tasks for the foremost capitalist countries and the purely negative program contained in the Stuttgart resolutions with regard to the colonial policy, can be replaced by the immediate positive policy of forming free national states out of oppressed colonies, protectorates and spheres of influence. The Third International is striving to create such new free states in the shape of Soviet republics. Needless to say these tasks are inseparable from the fundamental revolutionary tasks in the foremost capitalist countries. The liberation of oppressed countries is only possible because the power of the oligarchies is so shaken in the dominating countries, that their world driving force has force has lost its former irresistibility. The more the world colonial power of the oligarchies of the foremost countries, irrespective of whether the capitalist governments of these oligarchies at home. The Third International stands for the liberation of the oppressed countries, irrespective of whether the capitalist governments are in power or have fallen in the dominating countries, but at the present moment it is impossible to foretell which is likely to occur first: the liberation or the fall. In any case the immense positive international programme of the Third International is only possible owing to its fundamental universal revolutionary basis. It is that basis which makes the programme possible, and creates profound gulf between itself and the servile indefinite international programme of the Yellow Berne-Lucerne International.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n06-1919-CI-grn-goog-r2.pdf