Along with news from France and the International, Liebknecht reviews the upcoming German federal election held in March, 1871.

‘Letter from Leipzig, IX’ by Wilhelm Liebknecht from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 7 Nos. 31 & 32. April 1 & 8, 1871.

Leipzig, February 19, 1871.

To the Editor of the WORKINGMAN’S ADVOCATE:

Next Friday week the ballot battle will be fought in not-Austrian Germany. All parties do their utmost to stir the people up, and in the newspapers there is plenty of noise and puffing and mutual recrimination, but on the whole it cannot be denied that the great bulk of the population persists in a state of indifference such as I have never before witnessed on the eve of a general election. What life and commotion was there for instance, when in February, 1867, the first North German Reichstag had to be elected. By the catastrophe of the preceding summer’ the old German confederation had been shivered into atoms, universal suffrage, though stinted, yet a bewitching gift, had been granted for the first time since the wild year (1848), wonderful hopes arose in the popular mind, not least in those parts, where the new work of Count Bismarck was thoroughly loathed, and the throng to the ballot boxes was really astonishing–every vote thrown in being considered as a seed-corn of some undefinable, mysterious better thing coming. Well, none of these naive hopes were fulfilled; the Reichstag proved one great disappointment; instead of minding the interests of the people, it simply did Bismarck’s bidding, accepted the constitution framed by him to serve the ends of Junkerdom and Militarism, consented to nearly a redoublement of taxation, and condemned itself to an ignominious want of power. This was the euphemistically so called constituent Reichstag, and it separated after six or seven weeks having finished its work with the speed and docility of a properly managed steam engine. The elections that followed in the summer of 1867 showed a great falling off in public expectations and excitement. In all districts the number of voters was much smaller than in the preceding February, in many but half as large and smaller still. The new Reichstag, worked in the spirit of its predecessor, did what it was ordered and manifested a servility, which, by contrast, makes Bonaparte’s Corps Législatif–of lackeys–appear like a body of stern, catatonic republicans. Once it made some show of resistance to the commands of its master, but as a dim tallow rushlight in a big room renders darkness darker, more visible, so this faint attempt at manliness merely set the ordinary and general servility in relief.1 Alternately kicked and patted on the back by the government, this Reichstag expired in December last, the shouts of laughter still reverberating with which, in a moment of self-recognition and self-judgment, it had saluted its own activity in the matter of Emperor making. And now another Reichstag is to be elected for the same business, for the same purpose: to do nothing for the people, and to do all for Mr. Bismarck, to fetch and carry for him, when he bids and what he bids. To be elected, too, under conditions made more unfavorable to democracy and in fact to every independent party then at the elections in the summer of 1867; the public brain absorbed and confused by the war, militarism dominant as never before in German history, nearly half of Prussia under martial law, the opponents of Bismarck’s policy either in prison or in imminent danger of prison–what is to be expected of elections performed under such auspices? And how can anybody speak of free elections. Add to this widespread misery, intensified by a winter of unheard-of fierceness–since November it has been almost uninterruptedly cold, and last week the thermometer fell for the third time below 20 degrees, last night to -22 degrees and you will readily understand why there is little enthusiasm and effervescence with regard to the impending Reichstag elections.

Never mind the parliamentary comedy, for which we are to send the actor to Berlin. Shall we have peace? That is the question uppermost in people’s minds; the question of all questions. Not what peace shall we have? Not shall we get Alsace, Lorraine and untold millions, or shall we not? No purely and simply: Shall we have peace? Peace is the thing wanted. Alsace and Lorraine shrink into nothingness at the side of this immense boon, so long withheld and so long underrated, yes scoffed at.

As is always the case when the nerves have been overstrained for any length of time, by some exciting influence, a sudden and violent reaction of feeling has been caused in Germany by the late decisive turn of things in France. The great mass of the unthinking, who, while the din of battle rung in their ears, were mad with patriotic enthusiasm, and dreamed of a golden future of national greatness and prosperity springing from the blood-manured fields of perfidious Welshland, have got amazingly sobered down, and comparing their wild dreams with stern reality, they are fast verging into that uncomfortable state of mind which we Germans call “Katzenjammer” (misery of the cats2) and for which the English language has no word. Where is the practical substantial matter of fact gain? Glory, victory is all very well, but a hundred victories, be they ever so glorious, will not butter a single piece of bread; and annexations, do they bring us the slightest material advantage? Will they diminish taxation? Promote trade and commerce? Be productive of more liberty? Not a bit of it. Just the reverse. More soldiers will be wasted, and to keep them, more taxes, and to prevent the people from grumbling too loud, more policemen, and to keep these, again more taxes. And so we are a great, g-r-e-a-t nation abroad, and a herd of sheep at home, good to be shorn and eaten; as a nation, somewhat like that big Irishman, who in the beer-house played the bully, and in his lodging was beaten by his wife. Only to be beaten by one’s wife is not dishonorable, and may be excess of gallantry. Those of my countrymen in the United States who have with their German logic contrived to transfer their sympathies for American Lincoln upon the German Jefferson Davis, should come over to our renovated fatherland and personally and pocketally taste the Bismarckian blessings; I am sure half a year would be sufficient to bring them all to their senses, if they have any. It is cheap patriotism indeed, which will cosily enjoying American liberty, rant about German glory, and leave it to us to pay the costs for it. Why, to talk seriously, do these patriots from the distance stop in their distant adopted country, and not return to their glorious, real country? And a second question: Why is their adopted country still sought as a refuge by glory covered citizens of their real country? Why?

Of all mortals perhaps in the most perplexing position is now Count Bismarck. For several years before the present war, even before the famous interviews of Biarritz, he had been in secret relations with Louis Bonaparte, and part of what was planned between the two came to light when they fell out in July last. Count Bismarck, you will recollect, represented himself as an innocent lamb, tempted by that bad wolf, but the lamb had the cunning of a fox, and made a fool of the wolf, feigned to enter into his schemes, lured all his secrets from him, kept him from suspicion by dilatory negotiations till the bubble burst and the wolf could be shown in his true shape and character. Many people shook their heads at such dilatory negotiations between lamb and wolf, and did not exactly know what to think of it. Others, who knew what to think of it, were sent to Lötzen, the fortress, or had to hold their tongues to avoid being sent there. The friends of Count Bismarck shrugged their shoulders and muttered something about the inexpediency, nay stupidity of applying the rules of private morality to public morality. And the gentlemen of the Press Bureau received orders to treat the delicate matter rather shortly, but of course as a glorious feat of statesmanship on the part of Count Bismarck: for had he not Benedetti’s handwriting? That he could never have got it except by playing at the same game, was a reflection which did not occur to the gentlemen of the Press Bureau; and the victories intervening at the right time, all was soon forgotten in the patriotic ebullitions of the German heart.

II.

Bonaparte, whose interests demanded a speedy reconciliation with his old guest and friend, did not choose to indulge the whole truth, and allowed his friend-enemy the pleasure of the last word. At Sedan wolf and lamb met again; how they laughed together at the incredible credulity and gullibility of the unfeathered biped, called “Man,” is not reported by the day’s chronicler, but may easily be guessed by any individual not deprived of brains, who recollects the history of the wolf and lamb, and the different judgments which public opinions have passed upon them, always unanimous, always infallible; yesterday, raising that one to the skies, and condemning this one to the pit; today. reversing the thing, and condemning that one to the pit, and raising this one to the skies, and, tomorrow, throwing both into limbo, perhaps! No, certainly, only we must in patience wait for that tomorrow. Enough, there were agreements made at Sedan; and there were agreements renewed after Sedan; and the wolf was to be restored to his old power and the generous lamb was to do it, and tried hard to do it. When the news came that Paris would not hold out any longer and peace was nigh, the trunks were packed on Wilhelmshöhe. But, lo! Instead of the longed-for signal to depart, there arrived bad tidings, and the trunks had to be unpacked again. No idea of a restoration. The French people are so perverse. The stupidest peasant, that six months ago was ready to roast anyone alive (and did it) who opposed the good Emperor and government, would now do the same to anyone who seriously proposed to reimpose their good Emperor. Against stupidity the German proverb says, “Even God’s fight is vain.” “The promise was given, we did our best to keep it, and only a rogue does more than he can,” says another German proverb. So the affair stands now. Rather critical. Will Bonaparte speak now? Or will some means be found to shut his mouth? The unexpected change of ministry in Austria is not apt to sweeten Mr. Bismarck’s humor. The new ministers are new men; the political principles of most of them are unknown, but one thing is known of them all: they are no friends of Bismarckian Prussia. And they may mean much at the present conjuncture; of more interest for my readers will be, that Mr. Schäffle, the new Minister of Commerce, a political economist of note, has in his last work, though with some restrictions, acknowledged the correctness of Socialist views, and that his first work as a Minister was to induce the Emperor to grant an unconditional and complete political amnesty, by which our imprisoned friends, Oberwinder. Scheu, etc., have recovered their freedom, after a year’s confinement. This is a good beginning.

In a previous letter you will recollect what I wrote concerning the Press Bureau. To put you on your guard against certain newspaper correspondents from the seat of war, I will mention here that in Versailles a branch office of the Press Bureau has been established by Mr. Stieber, and that correspondents, who prove refractory, are either kept without any news, or, if they are “only Germans,” summarily sent home, as was Mr. Vogt, the excellent correspondent of the Frankfort Gazetta. The spirit which directed this branch office is the spirit of Mr. Stieber. And who is Mr. Stieber? Mr. Stieber is identified with the history of Prussia since 1845. Mr. Stieber, chief of the secret police, and of the field police, is the most influential man in Prussia, Mr. Bismarck not excepted. It may be said, in truth: Mr. Stieber is Prussia. I shall tell you more about him; for to say only this: you know Bonaparte’s two principal agents–Haussmann. Prefect of the Seine, and Pietri, Prefect of Police–you know what they have done, and what they are accused of. Put these two men together and you have Mr. Stieber.

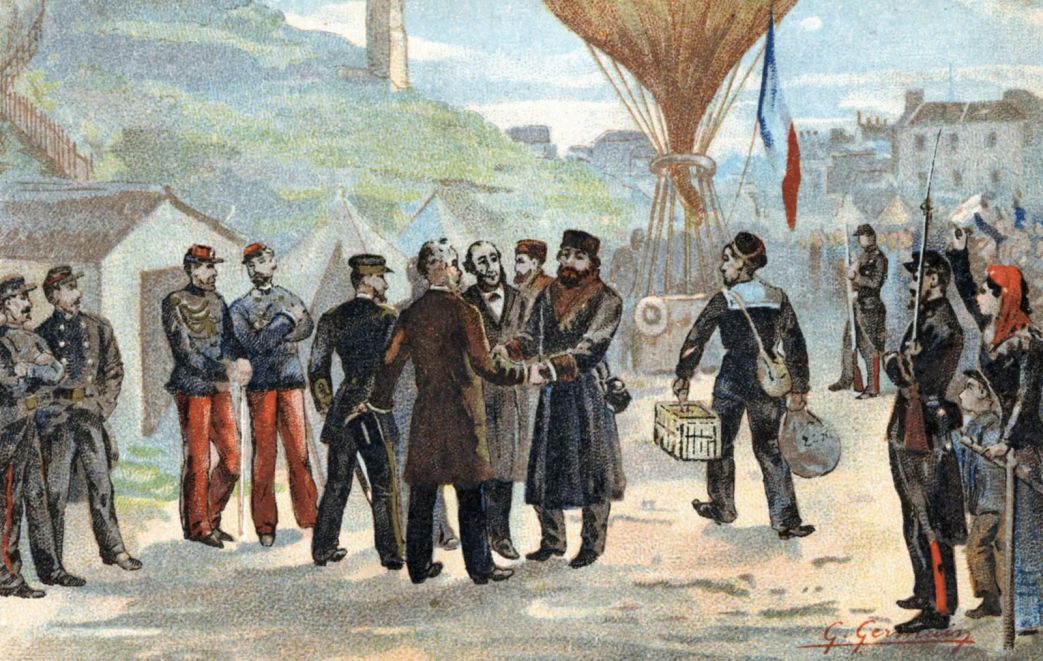

The news from France is all of a peaceful character. Gambetta’s demission, proving the brave Republican’s unselfishness, proved also that the extreme Radicals, the real men of action, have become convinced of the fruitlessness of further resistance, after Jules Favre’s coup d’état. By this step the danger of civil war has been removed, which united to war with the foreign invaders, might have destroyed the Republic. As things stand, the intrigues of the different pretenders hovering about, must not be taken au serieux (serious) in spite of Bismarck’s lurking in the background; the indecent haste in which their hungry vultures are flying to where they fancy carrion to gratify their appetite, would be ludicrous, if it was not so disgusting. France is no carrion. and will send the obscene birds of prey to the right about, or dispose of them on the spot. That Bonaparte or his boy with a regency are impossibilities, has been understood even by the King-Emperor of Prussia; and, as for the Bourbons and Orleans, they were impossibilities long before Bonaparte, who, in fact, never could have played the farce of the Second Empire, if they had not been impossibilities already twenty years ago. The sorry remnant of nobility that escaped the great revolution and a part of the clergy, do no doubt sigh for the restoration of the “legitimate monarchy,” but these two dust-covered, incurable and incorrigible factions of French society, have, (unless backed by a government) about as much moral, intellectual and physical influence in France, as the Mormons have in your United States. The Orleans, on the other hand, have no adherents, except amongst the higher middle class, which does not exist in the villages containing three-fourths of the population, and is in the towns far outnumbered by the workingmen, who are Social Democrats to a man, and by the épiciers (shopkeepers), who are nearly as unanimously Republicans. Under such circumstances I think there is no reason for apprehension from these quarters.

Most likely the armistice will be prolongated, and when the constituante has fairly met the treaty of peace at which diplomacy has been working hard since the end of last month, will probably be communicated to it at once. It would be foolish were I to conjecture here about secret negotiations, the issue and upshot of which will, thanks to the submarine telegraph, be known to you before this letter reaches your hands. Only this much: On the nature of the conditions will depend whether the treaty will be concluded as a treaty of peace or an armistice. If France is humbled, then there is no doubt that moral révanche will not satisfy her, and the 600,000 prisoners of war, set free by the treaty, put it in her power to begin the war anew at the first opportunity and with the best chances. And this reflection, it may be guessed, will in the impending deliberations of the constituante, guide the vote of many a deputy, who otherwise would call for guerre à outrance, war to the knife. We are not at the end of the tragedy, which stage managers Bismarck and Bonaparte put on the European boards in July last–the fifth act is to come yet, and poetic justice will be done–full and inflexible justice, let us hope.

The same papers that six and seven months ago were declaiming so much about the cruelty with which all Germans were expelled from Paris, are now compelled to own that thousands of my own countrymen have remained unharmed in the French capital during the whole time of the siege.” Altogether the matter of these expulsions has been totally misrepresented. The infamous edict of the Bonaparte government against German residents in France only commenced to be carried out, when that government was itself expelled, and under the Republican government none had to go, but such as either could not lay in a sufficient stock of food for the threatening siege, or had become suspect of aiding the approaching enemy. And this cannot be blamed in fairness. At all events the German authorities of the German fortress of Maintz have taken much harsher measures against their own countrymen. Most of the Germans who left Paris before the siege, did it of their free will, because they foresaw a time of scarcity and misery. Amongst those that stopped, was Moritz Hess, one of the founders of German social democracy. Born at Cologne, he went to Paris, I think in the year 1846, and from that period he has unremittedly by spoken word and by written word labored for the cause of social justice; being a member of the International Workingmen’s Association, he attended the Basel Congress, where the editor of this paper had the opportunity of meeting him. The last letter we had of Hess–by the by he is the Paris correspondent of the Volksstaat–was written at the end of August, and then he told us of his resolution to stay in Paris and to share the fate of the young Republic. Since then we had no news, and we were not without misgivings, until a few days ago happily all fears were dispersed by a paragraph in a Brussels paper, from which it appears that he is safe, in best health and of unshaken confidence in the final victory of right over might.

NOTES

1. I allude to the debates on capital punishment, which at the first and second reading of the penal codes was abolished, and finally at the third reading, by peremptory orders from the government, was restored again in the teeth of common decency and the public conscience of Germany and the civilized world.

2. This expression, which is the technical term for the state of body and mind following excessive drinking, takes its origin no doubt in the supposition that the cats, when performing their horrible concerts, must themselves feel the excruciating pains they inflict upon human ears.

3. Count Bismarck’s original expression. Very discreet.

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

Access to PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-04-01/ed-1/seq-1/

PDF of issue 2: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-04-08/ed-1/seq-1/