Brian O’Neill on the rise Ireland’s Blueshirt movement and its leader Eoin O’Duffy, looking at the particular dynamics of fascism in a country like Ireland, in the 1930s emerging from a colonial to neo-colonial status after its unfinished revolution a decade before.

‘Ireland Breeds a Serpent’ by Brian O’Neill from The New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 5. January 28, 1936.

DUBLIN. MUSSOLINI’S jackal raid on Ethiopia has produced an instructive crystallization in Irish politics. He has secured support for his imperialist crime from everything that is reactionary and dirty in Ireland: cunning support from Cosgrave’s United Ireland Party and its chain of subsidiary newspapers; circumspect support from many dignitaries of the Catholic church (opposition from none). And in General O’Duffy, now head of the National Corporative Party, he has found a veritable political fille de chambre. Here is O’Duffy on the Free State Government’s sanction measures against the fascist war (Irish Press, November 18):

“But for the Sanctions Bill there would be a hundred Italian vessels in the Liffey today loading cattle and other commodities, and a fine market would be available to this country. The Free State is backing the League against Italy despite the fact that Most Rev. Dr. Hinsley, Primate of England, said that if Italy lost the war it was a loss to Christianity, and that Monsignor Curran, head of the Irish College in Rome, regarded the action of the Dail as un- christian and dishonorable.”

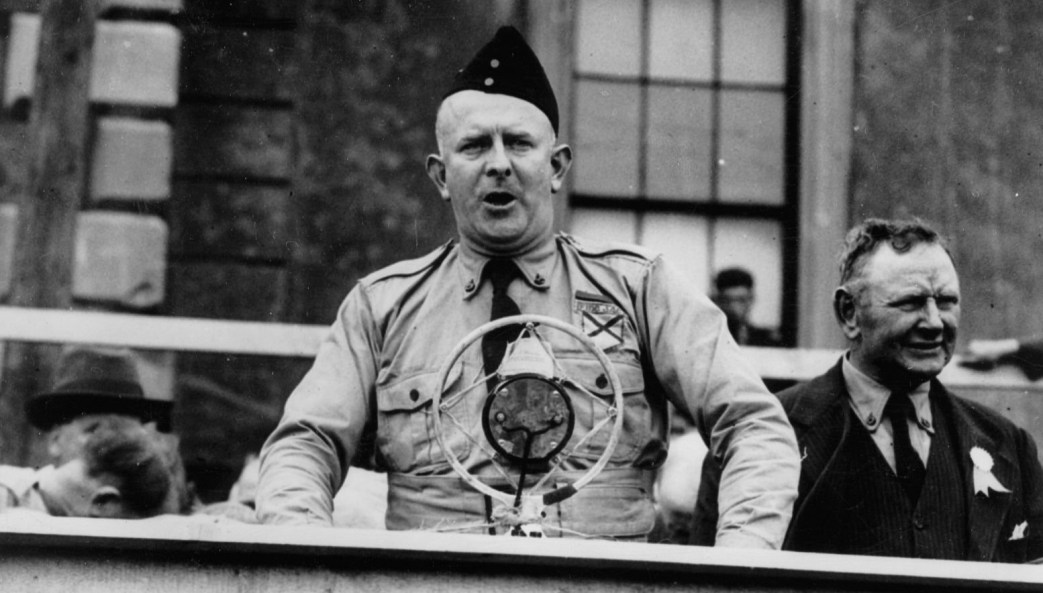

Americans know little of this man who urges the Irish people to support an imperialist war of conquest on the independence of a free nation. Some additional details may be interesting, for General O’Duffy is more than a fugleman of Mussolini; he has his own dreams; finance capital once laid its hands on him and anointed him Duce-to-be of Ireland.

Eoin O’Duffy was an officer in the Irish Republican Army during the war with England from 1919 to 1921. After the Treaty of 1921, when the dominant section of the capitalist class accepted a “Free State” inside the British Empire and betrayed the national struggle for republican status, O’Duffy went over to the Free State side. And he rose high. During the Civil War of 1922-24 he was in command of the Free State forces in Kerry, the stronghold of Republican resistance. Kerry’s roadsides today are marked with little crosses to tell by what means the Free State was established. Dorothy Macardle, in her book Tragedies of Kerry, gives a picture of O’Duffy’s troops in action:

“The soldiers had strong ropes and electric cord. Each prisoner’s hands were tied above him, then his arms were tied above the elbow to those of the men on either side of him. Their feet were bound together above the ankles and their legs were tied together above the knees. Then a strong rope was passed round the nine and the soldiers moved away…The shock came, blinding, deafening, overwhelming. For Stephen Fuller it was followed by a silence in which he knew he was alive. Then sounds came to him–cries and low moans, then the sounds of rifle fire and exploding bombs. Then silence again: the work was done.”

The Free State troops had disposed of their prisoners by means of a mine and electric fuse…

O’Duffy’s lack of squeamishness over Mussolini’s “civilizing” methods in Africa is not so strange; he knows how Kerry was “civilized!”

The General went still higher. The new Free State regime needed a strong police force. He became chief of police. The “civilizing” process was carried farther. Anti-imperialists were raided through the night, they were beaten up in jails, they were found unconscious in the street. Police and “G” men had a free rein, and all the pent-up hatred of them concentrated itself on O’Duffy’s head. So when the Cosgrave government was uprooted in the general election of 1932 and Eamonn de Valera came into power as head of the Fianna Fail Government, mass pressure forced O’Duffy’s dismissal. The General was out of a job. But not for long; he was hired again, for a new, grandiose role.

Big Business, which had solidly supported the Cosgrave regime, was taking stock of the situation in the months following de Valera’s election victory. Prospects of an early return of Cosgrave to power via the ballot box looked dreadfully slim. But across in Germany, in February, 1933, Hitler entered an automobile and rode to the Wilhelmstrasse and power. The imperialist bourgeoisie thought it would take a chance. Before most people in Ireland had realized what was happening, Cosgrave’s party and all kindred groups had fused into one organization, the United Ireland Party. The old conservative program and propaganda was dropped overboard; the Corporate State became the new policy. A “youth section” was formed and in a few months some thousands of Blueshirts were parading the country. And in place of the discredited Cosgrave, the new leader, General O’Duffy, appeared on the scene.

And the fledgling Goebbels and Feders got to work. The rotund, witless face of the heaven-sent Irish fuehrer appeared in the papers ad nauseam. The inspired speeches hit the front page in full–even when he forgot to say the piece prepared for him and blathered anything that came into his head. Little girls related touchingly in the fascist press how in the middle of the night seventeenth-century Red Hugh O’Donnell appeared at their bedsides, and he with his spectral finger pointed commandingly and his ghostly lips framing the words: “Follow O’Duffy!”

But the Blythes, the Hogans and other “theoreticians” who were now burning the midnight oil in company with Mein Kampf and the lucubrations of Mussolini were Goebbels only in intent. There was an odor of ham about their new “anti-capitalist” speeches and actors. O’Duffy himself was a country barnstormer compared with the continental prima donnas. And they were fatally handicapped from the outset. “In the colonial and semi-colonial countries certain fascist groups are also developing, but it goes without saying that here there can be no question of the kind of fascism that we are accustomed to see in Germany, Italy and other capitalist countries.” Dimitrov pointed this out at the Seventh World Congress. Ireland is an example. In Italy and Germany, fascism grew up as a force apart from the established political organizations of capitalism; fascism stepped forward as something new; fascism proclaimed itself the liberator of the nation. But in Ireland these factors for fascism were absent; rather they were present in reverse, as factors against fascism.

In the first place, the United Ireland Party was only a rechristened Cosgrave party; the personnel was basically the same, the continued support of big business and its press was blatant. In the second place, new gibberish about the Corporate State and “social justice” was hopeless to wipe out the known records of these men during their ten years’ rule. And in the third place, how could they pose as the champions of Ireland?–they who had borrowed English arms to crush the Republican forces in 1922, who had outlawed and bludgeoned the anti-imperialist movement for ten bloody years, and who even now, spilt all their social demagogy, placed the maintenance of the British connection and resistance to full independence in the forefront of their program!

It took time before the ceaseless educational work of the Communist Party exposed to the Irish people the social role of Blueshirtism. But then the masses saw its anti-national, imperialist nature clearly. And they smote it hip and thigh. Whenever the Blueshirts paraded publicly they were mobbed. At Dundalk and Drogheda it took bayonet charges by war-helmeted troops to save them. In Tralee armored cars were called out. The urban masses gave them no foothold anywhere.

In the countryside, however, fascism hoped for a mass basis. The farmers were suffer ing as a result of the crisis, aggravated by Britain’s “econmic war” on the Free State. The ranchers were solidly imperialist; their markets depended on the Empire link. A no-rate campaign was organized by the fascists, and in Cork and other countries local administration was almost hamstrung. The fascists went a step farther. They organized refusals to pay the annuities (the compounded rent) to the State. (When in power Cosgrave had made it a criminal offense to advocate non-payment of annuities!) And when the de Valera government at last began to make seizures of stock in areas where non-payment clearly was due to the fascist conspiracy, the Blueshirts risked a desperate hazard. State seizures were met by violence, roads were barricaded and railroad lines were torn up to prevent the transport of seized cattle.

O’Duffy and the more hare-brained Blueshirts were prepared to carry out the campaign to the end. But at this point the scared bourgeoisie drew back. They were appalled by the dangers; a campaign such as this, making use of the revolutionary slogan “Pay no Annuities,” might lead to the last thing they wanted. It might set the spark to a new land war and they would perish in the blaze. So O’Duffy was called to book.

But to their horror, the Executive of the United Ireland Party found their hired. fuehrer impervious to reason. They had no other choice. The heaven-sent leader was fired!

O’Duffy gaped at the men who a few hours before had been heiling and saluting him, collected his last pay envelope and departed breathing vengeance. He took a considerable section of the Blueshirts (the uniformed section) with him and for weeks Ireland was uproarious over the daily exposures and counter-exposures. Indicating their nature is their unpublished story of a high official of the U.I.P. explaining the affair to subordinates: “Jesus, I tell ye O’Duffy is mad. I spent the last three months writin’ corrections to the papers. I’d be afraid to open the paper in the mornin’, wonderin’ what he’d been sayin’ the day before. And the fine speeches we gave that man to say!”

SO THE United Ireland Party has got the old politician, Cosgrave, at its head again; its Blueshirt section is kept quiet; and it is soft-pedalling on the Corporate State. And O’Duffy has transformed his followers into the “National Corporative Party,” brazenly fascist.

The man’s a playboy, true enough and his party is diminutive. But it would be highly dangerous for the Irish working class to regard him as a harmless amadhan and to think that fascism has been routed for all time.

“Fascism does not come into existence because a “leader” arises. On the contrary, because the bourgeoisie requires fascism, a “leader” is created from such materials as can be found…The development of a specific fascist movement is a complicated process, involving a considerable “trial and error” of rival movement, before the successful technique is found. Only fools will laugh at the awkwardness of these embryonic stages, and not realize the character of the serpent that is being incubated.” (R. Palme Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, p. 259.)

O’Duffy in fact has trumpeted a new, more double-dealing and dangerous policy, since his break with his former employers. He has attended the International Fascist Congresses at Montreux, etc. And his new mentors have advised him out of their long experience. He has been told that he can make little headway among the masses without jettisoning the old, clumsy “membership of the Commonwealth” platform and draping himself in national colors. As a result, he is now fulminating against Britain, flourishing the Tricolor, “accepting” the Republican Proclamation of Connolly and Pearse in 1916 and declaring his intent to build a new government on the Hill of Tara!

And the united front movement is still in its most embryonic stage in Ireland. The leaders of both the Free State and Northern Ireland Labor Parties still take their cue from the British Labor Party officialdom, the rampart of the resistance to unity in Europe. The breach in the revolutionary nationalist ranks has not yet been overcome; the Irish Republican Army and the Republican Congress are still at cross purposes. But the mass feeling for unity is growing. And the Irish people have won the first round against fascism. If the United Front can be won, neither O’Duffy nor any other brand of fascism will find it easy to succeed in Ireland.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1936/v18n05-jan-28-1936-NM.pdf