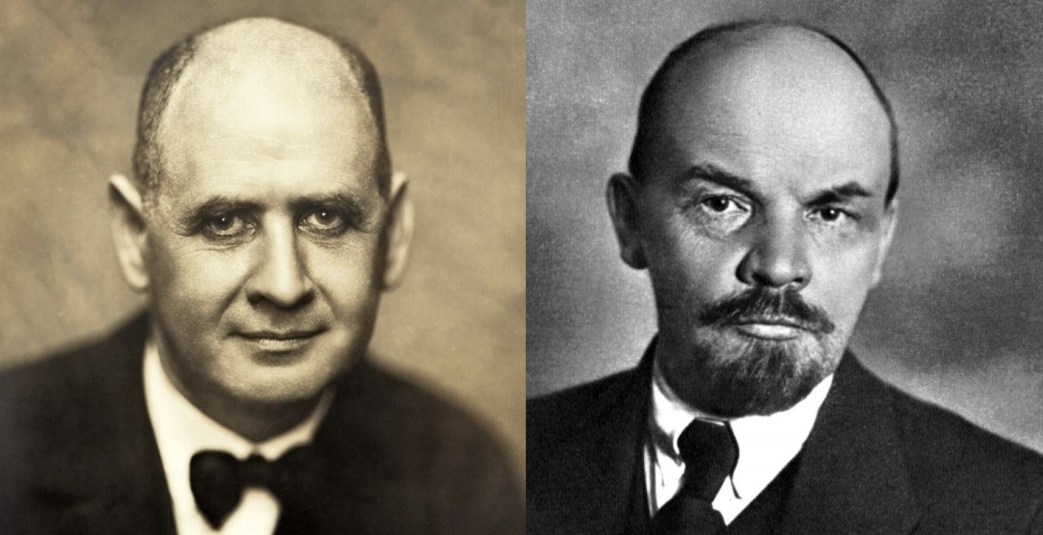

After the failed ‘March Action’ in 1921, German Communism entered another crisis. Those events were discussed at the Third Comintern Congress later that year where ‘ultra-lefts’ were denounced and the rising criticized. In this letter to the United Communist Party at its following congress, Lenin addresses the situation as well as relations to the Communist Workers’ Party of Germany (the K.A.P.), and most importantly Paul Levi, a leading figure of the Party recently expelled for his public criticism of the alleged ‘putschism’ of the Party in March. The letter is an excellent example of Lenin’s approach to debates in the early Communist International, as well as an insight into the politics of those days.

‘Letter to the German Communists’ by N. Lenin from Bulletin of the E.C.C.I. Vol. 1 No. 3. October 21, 1921.

I had intended to write a detailed article giving my views on the lessons to be learned from the Third Congress of the Communist International. Unfortunately I have been prevented by illness from doing it. The Congress of your party having been fixed for the 23rd of August, I have to hurry with this letter and finish it in several hours, so as not to be late in dispatching it to Germany.

As far as I can judge, the position of the Communist Party in Germany is a very difficult one. This may be easily understood.

First and above all, the international position of Germany since the close of the year 1918 has suddenly and acutely sharpened the revolutionary crisis in the country, pushing the vanguard of the proletariat towards the immediate seizure of power. At the same time the German as well as the whole international bourgeoisie, excellently armed and organised, taught by the “Russian experiment”, fell upon the revolutionary proletariat of Germany with vicious hatred. Tens of thousands of Germany’s best men, of her revolutionary workers, have been murdered and tortured by the bourgeoisie, by its heroes–Noske and Co., its direct servants, the Scheidemanns etc., its indirect and “refined”—and therefore all the more valuable–help- mates, the heroes of the “Two-and-a-half International” with their disgusting want of backbone, their hesitation, pedantry and petty bourgeois souls. The armed bourgeoisie set traps to the defenceless workers, murdered them in masses, killed their leaders, systematically waylaying them one after the other and making excellent use of the hue and cry raised by the social democrats of both shades–the Scheidemanns as well as the Kautskys. But during the crisis the German workers were left without a truly revolutionary party, owing to the belated split and to the influence of the accursed tradition of “unity” with the gang of flunkeys of capital, of whom some are mercenaries (the Scheidemanns, Legiens, Davids & Co.) and the others unprincipled (the Kautskys, Hilferdings & Co). Every honest and conscious worker who accepted the Basel manifesto of 1912 on its face value and not for what it really was a mere shift on the part of the rascals of the “Second” and “Two- and-a-half” sort loathed the opportunism of the old German social democrats. This loathing–the most honourable and highest feeling of the best of the oppressed and exploited masses–blinded the people. It kept them from thinking the thing out coolly and from working out their own correct strategy in answer to the first-rate strategy of the armed and organised Entente capitalists who have learned their lesson from the “Russian experiment” and are supported by France, Britain and America. It was this loathing that pushed the workers to premature risings.

This is why the development of the revolutionary workers’ movement in Germany took such an extremely hard and painful course, especially after the close of the year 1918. Yet it went on and is still going on unswervingly. It is an undeniable fact that the working masses, the actual majority of the toilers and the exploited in Germany are gradually moving to the left. This applies to the workers belonging to the old menshevist trade unions (i.e. the unions which serve the bourgeoisie), as well as to the unorganised or practically unorganised workers. What has to be done, and what will be done by the German proletariat, what will guarantee freedom to it, is to keep cool-headed and steady; systematically to correct past mistakes; with set purpose to win a majority among the working masses inside and outside the trade unions; patiently to build up a strong and clever Communist party which would really be able to lead the masses in any and all emergencies; to work out a strategy that would come up to the standard of the best international strategy of the most “enlightened” (by centuries of experience in general, by the “Russian experiment” in particular) and progressive bourgeoisie.

On the other hand the difficulties of the German Communist Party are now enhanced by the secession of the inferior Communists of the Left (the “Communist Labour Party of Germany”, K.A.P.D.) and of the Right (Paul Levy with his worthless magazine–Our Path–or The Soviet).

We have given the “left” elements or the “K.A.P.”-ists plenty of warning on the international arena, since the time of the Second Congress of the Comintern. As long as sufficiently strong and experienced Communist parties have not yet grown up, if only in the chief countries, we have to suffer the semi-anarchistic elements at our international meetings. To a certain extent their presence is even useful. It is useful in so far as these elements serve as a practical warning for the inexperienced Communists, as a sort of example “ab contrario”, and also in so far as they themselves are still able to learn something. All the world over anarchism has split into two different tendencies. This phenomenon is not of recent occurrence, but dates back to the beginning of the imperialistic war of 1914-1918. One of these tendencies is pro-Sovietist, the other anti-Sovietist, the one is for the dictatorship of the proletariat, the other against it. We must let this process of disintegration in anarchism grow and mature. Scarcely anybody in Western Europe has been through a revolution of more or less importance. The lessons of the great revolutions have practically been forgotten there. As to passing from the mere desire to be revolutionary, from mere talk (and resolutions) about the revolution to real revolutionary work, it is a very difficult, slow and painful process.

Of course, we may and must suffer the semi-anarchistic elements only to a certain extent. In Germany we have put up with them for a very long time. The Third Congress of the Communist International has put them an ultimatum with a fixed term. If they have now left the Communist International of their own accord, so much the better. Firstly, they have saved us the trouble of expelling them. Secondly, all the wavering workers, all those who were leaning towards anarchism out of disgust with the opportunism of the old social democrats have now been shown most circumstantially and clearly and have had all the proofs laid down before them, corroborated by accurate facts, that the Communist International has been patient, that it did not turn out the anarchists immediately and unconditionally, but listened attentively to what they had to say, and helped them to learn.

The less attention is now being paid to the K.A.P.-ists, the better. We merely advertise them by carrying on a controversy with them. They are too far from being clever. To take them seriously would be wrong; to be angry with them is not worth while. They neither have nor will have influence with the masses, if we ourselves forbear from mistakes. Let us leave this paltry tendency to die a natural death. The workers will realise its worthlessness by themselves. Let us more thoroughly make propaganda for and apply in practice the decisions of the Third Congress of the Comintern as to organisation and tactics, and less ardently advertise the K.A.P.-ists through our polemics with them. The infantile sickness of “left” communism is passing and will pass as the movement grows.

It is equally wrong to help Paul Levy–as we are doing now–and to advertise him by carrying on a controversy with him. All he wants is that we should argue with him. We must forget him now that the Third Congress of the Comintern has come to a decision on the matter. We must concentrate all our attention and all our efforts on peaceful work (without frictions, without polemics, without thinking of yesterday’s scuffles), on businesslike and positive work in the spirit of the decisions of our Third Congress. To my opinion Com. K. Radek’s article “The Third World Congress on the March Action, and Future Tactics” (see the Rote Fahne, the central organ of the United Communist Party of Germany, July 14th and 15th 1921) sins considerably against this general and unanimous decision of the Third Congress. This article, which has been forwarded to me by a comrade belonging to Polish Communist circles, is without any necessity whatsoever and much to the detriment of the cause–aimed not only at Paul Levy (this would not have mattered in the least), but also at Clara Zetkin. Yet Clara Zetkin herself, when in Moscow, during the Third Congress, concluded a “peace treaty” with the C.C. (the “Zentrale”) of the United Communist Party of Germany, agreeing to work together on friendly lines, without sectarian spirit. This treaty has been approved by all of us. Carried away by this ill-timed controversy, Com. Radek has come to make altogether false statements. Thus he says that Clara Zetkin is “putting off” (verlegt) “all general action of the party” (jede allgemeine Aktion der Partei) “until the day when the large masses will rise” (auf den Tag, wo die grossen Massen aufstehen werden). By using such methods Com. Radek is rendering Paul Levy the best service he could have dreamt of. All that Paul Levy wishes is that the issue be discussed endlessly, that as many people as possible be drawn into it and that efforts be made to frighten Clara Zetkin off from the Party by means of polemic breach of the “peace treaty” concluded by her and sanctioned by the whole Communist International. By his article Com. K. Radek has given a splendid example of the way in which Paul Levy is being helped from the “left”.

I must now explain to the German comrades why I kept on defending Paul Levy for a considerable time at the Third Congress. I did it in the first place because I had made Levy’s acquaintance through Radek in Switzerland in 1915 or 1916. Levy was already a Bolshevik then. And I cannot help somewhat mistrusting those who declared themselves in favour of Bolshevism only after its victory in Russia and a number of victories on the international field. This is, of course, rather an unimportant reason, since I know Paul Levy very little personally. Of much greater importance is the second reason, namely, that Levy is essentially in the right in much of his criticism of the March rising of 1921 in Germany (but, of course, not when he calls this rising a “Putch”. This assertion of Paul Levy’s is nonsense.)

It is true, Levy has done all that was possible and much of what was impossible to weaken and spoil his criticism and obscure to himself and others the essence of the question, by adding so many details in which he was obviously wrong. He has clad his criticism in an inadmissible and harmful shape. While preaching a careful and well weighed strategy to others, Levy has done more foolish a thing than any boy would have done, by flinging himself headlong into the fight so prematurely and without any preparation, so stupidly and so much against all reason that he was bound to lose the “battle” (and has for many years to come spoiled and hampered his own work), although he might and should have won it. Levy has behaved like an “intellectual anarchist” (if I am not mistaken, they call it “Edelanarchist” in German), instead of acting like one of the organised members of the proletarian Communist International. Levy has thus committed a breach of discipline.

By this series of unspeakably foolish mistakes Levy has made it difficult to concentrate one’s attention on the essence of the thing. Yet the essence of the thing, i.e. the estimate and the correction of the numerous mistakes made by the United Communist Party of Germany during the March action of 1921 was and is of enormous importance. To point out and correct these mistakes (which some have extolled as a pearl of Marxist tactics) one had to stand on the right wing at the Third Congress of the Comintern. Otherwise all the line of conduct of the Communist International would have been wrong.

I defended and had to defend Levy in so far as I saw before me such adversaries of his who were simply crying out against “Menshevism” and “Centrism”, without any desire to see the mistakes of the March rising and the necessity of pointing them out and correcting them. Such people were turning revolutionary Marxism into a caricature, and the struggle against “Centrism” into merry sport. There was danger of these people doing the greatest possible harm to the whole cause, for “no one on earth is able to compromise the revolutionary Marxists, provided they won’t do it themselves”.

I said to those people: Supposing Levy has become a menshevik. Knowing him very little myself, I’ll not gainsay it, if I have proofs of it. But it has not been proven yet. So far all that has been proven is that he has lost his head. To declare a man a menshevik on account of that only, is both childish and silly. It is slow and tedious work to train experienced and influential party leaders. Yet without it the dictatorship of the proletariat, its “unity of will” will necessarily remain a mere phrase. In Russia the training of a group of leaders lasted fifteen years (1903-1917), fifteen years of struggle against menshevism, fifteen years of persecution by tzarism, fifteen years among which were the years of the first revolution (of 1905),–which was a great and powerful revolution. And yet with us too there have been sad cases of even the very best comrades “losing their heads”. If the West-European comrades imagine that they are safe from such “sad cases”, it is childishness on their part which we cannot help fighting against.

Levy had to be expelled for breach of discipline. The tactics had to be fixed on the basis of pointing out and correcting the mistakes of the March action of 1921 with greatest possible details. If after this Levy should go on behaving as he did he will confirm that we were right in expelling him, and it will be proven to the hesitating or wavering workers with still greater force, still more convincingly that the decisions of the Third Congress with regard to Paul Levy were correct.

And the more careful I was at the Congress in weighing Levy’s mistakes, the greater the certainty with which I can say that Levy has hastened to confirm our worst suppositions. I have seen his paltry review, Our Path. (No 6, July 15th, 1921). As can be seen by the statement published by the editor at the very head of the journal, the decisions of the Third Congress are known to Levy. And what is his reply to them? Menshevist stock-phrases about “the great ban” (grosser Bann), about “canonic law” (kanonisches Recht) and about his going to “weigh” these decisions “in full freedom” (in vollständiger Freiheit). Well, can there be any greater freedom than that enjoyed by a man who has been relieved of the burthen of being a member of the Party and of the Communist International! And, mark ye, party members will contribute to his review anonymously!

To begin with-a dirty trick against the party, an attack from behind the corner, a spoiling of the work of the party.

Thereupon–a weighing and a substantial discussion of the decisions of the Congress.

This is splendid.

But it is just through this that Levy is digging his own grave.

Paul Levy wishes to continue the brawl.

It would be the greatest strategic error to comply with his desire. I should like to advise the German comrades to prohibit all controversy with Levy and his paltry paper on the pages of the daily press of the party. Do not advertise him. Do not let him divert the attention of the fighting party from the important things to the unimportant. In case of urgent need, carry on your controversy in weeklies and monthlies, or in pamphlets. If possible, do not give the K.A.P.-ists and Paul Levy the pleasure of calling them by their names, and speak of them merely as of “some critics somewhat wanting in brains who insist upon considering themselves Communists”.

I am told that at the last session of the enlarged Central Committee (Ausschuss) even Friesland, of the left wing, was obliged to speak out sharply against Maslov who is playing at radicalism and wishes to practise the sport of “banning the centrists”. We have had samples of Maslov’s unwise behaviour (we are putting it mildly) here in Moscow. Really, the German party ought to send this Maslov and two or three of his adherents and fellow-combatants who obviously do not wish to keep to the “peace treaty” and show more ardour than is reasonable, to Soviet Russia, say for two years. We should find useful work for them to do. We should mould them all over again. The international and German movement would undoubtably vastly profit by it.

The German Communists must stop the internal strife at all costs, cut off the quarrelsome elements from both sides, forget about Paul Levy and the K.A.P.-ists and betake themselves to real work.

And, to be sure, there is plenty of work to be done.

The resolutions of the Third Congress of the Communist International on tactics and organisation mark a great progress of the movement. We have to put forth all our strength to carry these resolutions into being. The task is difficult, but it can and must be done.

First of all the Communists have had to declare their principles all over the world. This was done at the First Congress. That was the first step.

The second consisted in shaping the organisation of the Communist International and working out the conditions for the admission to it,–the conditions for the actual separation from the centrists, from the direct and indirect agents of the bourgeoisie within the labour movement. This was done at the Second Congress.

At the Third Congress businesslike, positive work had to be started; we had to lay down concretely–bearing in mind the practical experience of the Communist struggle–how the work was to be carried on in future as regards tactics and regards tactics and organisation. We have made this third step. We have an army of Communists all the world over. As yet it is badly trained and organised. It would do the cause the greatest possible harm to forget this truth, or to be afraid to acknowledge it. Carefully and rigorously testing oneself, studying the experience of one’s own movement and learning from it how to teach and organise, we will put this army to the test in a business-like way in all kinds of manoeuvres, in operations involving attack and retreat. Unless this long and hard training be gone through we cannot win.

The “key” of the situation of the international Communist movement in summer 1921 was that some of the best and most influential parts of the Comintern did not interpret this task quite correctly. They were just a little overdoing this “fight against centrism”, were ever so little overstepping the line beyond which this fight turns into sport, and revolutionary Marxism begins to be compromised.

This was the “key” note of the Third Congress.

The thing itself was not much overdone. But the danger it entailed was enormous. It was difficult to fight it, as those who overdid it were really the best and most devoted elements without whom there would possibly have been no Comintern at all. In the amendments to the theses on tactics, reprinted in the Moscow in German, French and English and signed by the German, Hungarian and Italian delegations, this exaggeration becomes quite evident, the more evident that the amendments were brought in already after the resolution had been finally drafted (after long preparatory work and careful weighing from every point of view). Those amendments were rejected, and thanks to this decision the line of the Comintern was straightened out, and that meant victory over the danger of exaggeration.

Yet exaggeration, if it is not corrected, would undoubtedly ruin the Comintern. For “no one on earth will be able to compromise the revolutionary Marxists, provided they will not do it themselves”. No one on earth will be able to prevent the victory of the Communists over the Second and Two-and-a-half Internationals and, as applied to the West of Europe and to America of the twentieth century, after the first imperialistic war, this means that no one will be able to prevent their victory over the bourgeoisie–provided the Communists themselves will not hamper it.

Yet to overdo the thing, if ever so little, is equivalent to impeding victory.

To overdo the fight against centrism is to save centrism, to strengthen its position and its control of the workers.

In the period between the Second and Third Congress we have learned to fight centrism victoriously on an international scale. This is proved by facts. And we will continue this fight, (as shown by the expulsion of Levy and of Serrati’s party) to the finish.

But we have not yet learned on an international scale to fight exaggeration in the struggle against centrism. However, as the work and results of the Third Congress show, we have realised this defect of ours. And just because we have realised our deficiency, we shall get rid of it.

Once we have done it we shall be invincible, for the bourgeoisie cannot keep its power in Western Europe and America without being supported from within the proletariat (through the bourgeois agents of the Second and Two-and-a-half Internationals).

A more careful and thorough preparation for new, ever more decisive battles, offensive as well as defensive ones–that is the most essential and important part of all the decisions of the Third Congress.

“…Communism will become a live force among the masses in Italy, if the Italian Communist Party will only maintain an unbroken, unbent front against the opportunistic policy of the Serrati school. But at the same time it must succeed in identifying itself with the masses of the proletariat in the unions, in strikes, in fights against the counter-revolutionary fascisti, in consolidating their movements, in converting their spontaneous actions into carefully planned struggles…

“…The United Communist Party of Germany will the more successfully be able to lead the mass movements, the better it will in future adapt its fighting watchwords to the to the actual situation, studying this situation most carefully, and carrying through the actions with complete unity and discipline…”

These are the most essential parts of the resolution on tactics as adopted by the Third Congress.

“The important task of the present” (see Paragraph 3 of the resolution on tactics) is to win over the majority of the proletariat to our side.

Of course, we do not interpret this winning over formally, as the heroes of the petty bourgeois “democracy” of the Two-and-a-half International are doing. When in July 1921, in Rome, the whole proletariat, the reformist members of the trade unions as well as the centrist proletariat from the Serratian party sided with the Communists against the fascisti, this was a winning over of the majority of the working class to our side.

It was far from being a decisive victory, it was only a partial, momentary and local one. Yet by it we had then won the majority. Such a conquest is possible even when the majority of the proletariat follows the bourgeois leaders or those who are carrying through the bourgeois policy (as the leaders of the Second and the Two-and-a-half Internationals are doing), or when the majority of the proletariat is hesitating. This process of winning over is in constant progress everywhere and in every possible way. Let us prepare is thoroughly and carefully, without missing a single serious opportunity given by the bourgeois forcing the proletariat to rise for the struggle, let us correctly estimate the moments when the masses of the proletariat cannot fail to rise together with us.

Thus victory will be guaranteed to us, however severe the partial defeats, however difficult the different moves in our great campaign.

Internationally our tactical and strategic methods are still behind the excellent strategy of the bourgeoisie which, taught as it is by the Russian example, will not be “caught napping“. Yet our reserves are infinitely greater than theirs. As to strategy, we are learning our lesson, we have marked progress in this “science” by turning to account the mistakes of the March rising of 1921. We shall master this “science” completely.

In a great many countries our parties are as yet very far from being what real Communist ought to be–true vanguards of the only really revolutionary class, with all the party members participating in the struggle, the movement and the every-day life of the masses. But we are aware of this deficiency of ours, we have shown it up clearly in the resolution on party work as adopted by the Third Congress. We shall do away also with this defect.

Comrades, German Communists! Allow me to finish my letter with the wish that your Party Conference, which is meeting on the 22nd of August, may with a firm hand do away once forever with the paltry struggle against the elements that have seceded and gone to the left and to the right. We have had enough of internal party strife. Down with all who should still wish to continue it directly or indirectly! Our tasks are much clearer, much more concrete and obvious to us now than they were yesterday. We are not afraid openly to point out our mistakes, in order to correct them. We will now devote all the strength of the party to perfecting its organisation, raising the quality and improving the essential part of its work, establishing closer contact with the masses and working out ever more correctly and accurately the tactics and strategy of the working class.

With Communist greetings

August 14th, 1921.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/umn.31951002047920w