A snapshot of the different wings of early French Communism through this survey of the journals La Revue Communiste, Bulletin Communiste, Le Soviet, and La Vie Ouvrière along with the tendencies and organizations they represented.

‘Communist International Press in France’ from Communist International. No. 13. Fall, 1920.

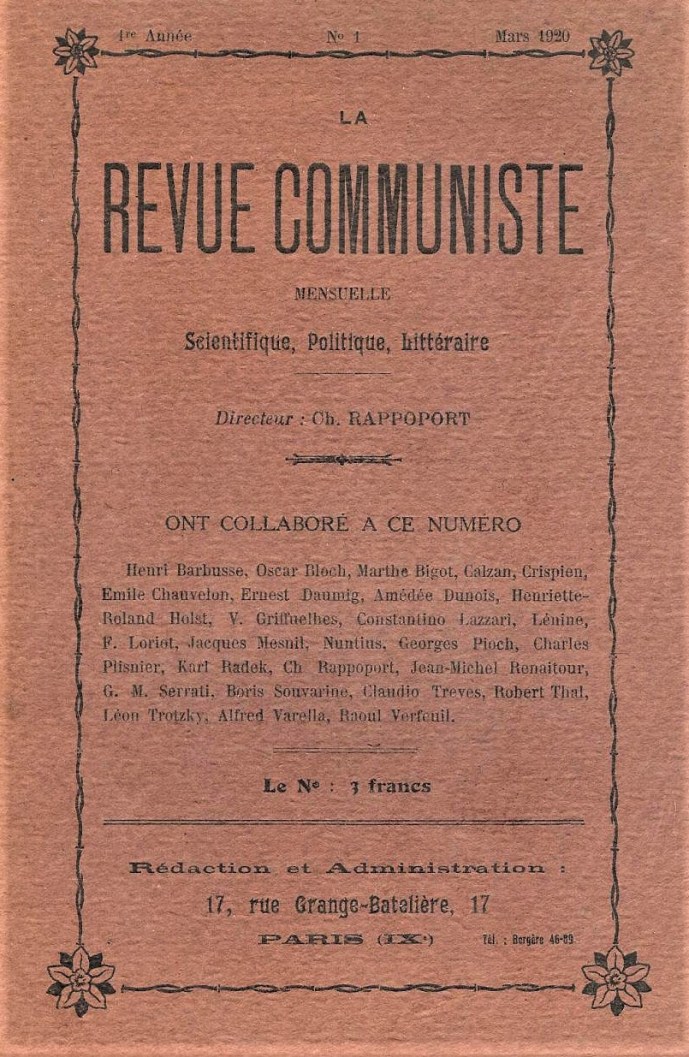

La Revue Communiste. Paris. Ch. Rappoport. Editor, No. 1.

In France a serious journal dedicated to the study of Communism was more necessary, possibly than in any other country. In order to put an end to the confusion of ideas reigning among the “Centrists” and the “Reconstructionists,” an organ of the Press with a clear program was absolutely necessary. Judging by the article in the first number of La Revue Communiste, signed by Ch. Rappoport, such a paper is now founded. “Why and how have we become Communists?” asks the author, and his answer is as follows: “The opportunist reformism and nationalistic Socialism of the Second International have, as every one knows already, become hopelessly bankrupt.

“We can affirm with assurance that the Second International has died of a chronic disease, which had to lead it inevitably to this tragic end. The disease consisted in the contradiction between its revolutionary theory, based on the class struggle, and its reformist practice, based on the collaboration of the classes.

“The name of the Second International itself was a compromise. It was a Socialist or a Social-Democratic International, whereas the creators of the contemporary proletarian movement were Communists. The word “Socialism”—I affirm this on the basis of information received by me personally from Engels himself—was accepted by Marx and Engels “against their will.”

Side by side with such well-time communications in La Revue Communiste, we meet with the articles of our valiant Comrades Loriot, Souvarine, Marthe Bigot, and Georges Pioch. Two poems dedicated by the latter to the “Russian Victorious Soviets,” and to “Comrade Trotsky” prove that a real poet has understood the proletarian revolution, and that the same may be loved by a poet.

Much space is given in the journal to the Russian theorists of Communism. It is quite inadmissible, however, that the names of Crispien and Däumig should figure alongside with the names of our theorists. This is only apt to create confusion among the French and German workers.

In this number there is also an article signed by the former secretary of the General Confederation of Labour, Comrade Griffuelhes, one of the French theorists of syndicalism, who has now joined the ranks of the Communists.

Bulletin Communiste (organ of the Committee for the Third International). A weekly paper, Nos. 1 to 10.

The Bulletin is the official, organ of the French Communists. It has reproduced many of the articles that have appeared in the COMMUNIST INTERNATIONAL. Among many interesting letters there is one from our Austrian comrade, Otto Maschl. The answer of Loriot to the reformists, printed in the fourth number of the paper, is worthy of attention. The reformists find a pleasure in noting the insufficient “revolutionary consciousness” in France. Loriot writes: “But did the Russian popular masses possess to any larger degree the consciousness of their historical predestination? Popular consciousness is in a state of constant evolution…The degree of consciousness exercises a much smaller influence on the revolution than the revolution itself on the degree of consciousness.”

Among the numerous articles on the French movement in the Bulletin, the appeal of the Communist students of Paris, deserves attention. It bears witness to the fact that the élite of the French youth is highly conscious of the duties incumbent on it.

Le Soviet (organ of the Communist Federation of Soviets). Paris. Nos. 1, 2, and 3.

The Communist Federation of Soviets (French section of the Communist International of Moscow) insists particularly on the necessity of propaganda and practical introduction of the Soviet principle. The first number includes an open letter to Senator Raymond Poincaré, signed by Emile Giraud, in which the author asks for explanations from Raymond Poincaré on several questions: “If only, in the course of the next few days, the popular masses of Paris who have had enough of you, do not find it necessary to carry your head through the streets on the point of a lance, to show it well to all your accomplices, a circumstance which would simplify the juridicial examination of your case.”

Each of these lines will probably cost its author a year of prison. Le Soviet has already had to experience the confiscation of its correspondence and a raid on its premises. These unpleasant facts will certainly not diminish the proportions of its propaganda. Comrade Chauvelon is giving articles on his study of Marxism; Alexandre Lebour, Hanot, and others are following the course of current affairs. From afar we can only rejoice at the various shades and tendencies of the French Communist press; however, the multiplicity of the organisations is causing us some anxiety. The Communist Party, the Communist Federation of Soviets, the Committee of the Third International, are forming three organisations, whereas unity in the Communist movement is evidently an essential condition of its force and its future development. One would like to believe that the fighters for the Soviets are acting and will be acting in close unity with the other French Communists.

The most important thing is that it is time to understand that it is not ‘‘hot-bed’’ Soviets that should be organised, but that real Soviets are the premise to a wide revolutionary movement of the masses. Otherwise it is only “playing at Soviets.”

La Vie Ouvrière (Paris). A weekly paper edited by P. Monatte, chiefly the organ of the French Communist-Syndicalists.

It has just carried through an energetic campaign in favour of the persecuted Communists of the Ruhr province. It has helped to acquaint France with the great Hungarian writer, André Latzko, sentenced to death in Budapest for his participation in the work of the Soviets. The large dimensions and rich contents of La Vie Ouvrière make it an excellent organ for a wide propaganda. Therefore, like Loriot, Souvarine, and many others, Pierre Monatte is now in prison, accused of conspiring against the State.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://archive.org/download/communist-international-no.-1-17-1919-may-1921/Communist%20international%20no%2011-13%201920.pdf