A fantastically informative article on the history unions in the meat packing industry. From the 1904 strikes, through the 1917 founding of the Stock Yards Labor Council led by John Fitzpatrick, William Z. Foster, and J.W. Johnstone, to the 1921 strike and its failure.

‘Making and Breaking the Packinghouse Unions’ by “A Packinghouse Worker” from Labor Herald. Vol. 1 No. 1. March, 1922.

THE collapse of the national strike of the packinghouse workers at the end of January marks the close of an epoch in the long and bitter struggle to establish trade union organization in the packing industry. Menaced by the establishment of company unions and radical wage cuts, the workers struck desperately in the face of great odds and covered themselves with glory. They succeeded in tying up large sections of the industry for eight weeks. But they did not have a chance; they were whipped from the start. Their organization went into the fight weak and demoralized. Besides being destitute alike of funds and spirit, it was afflicted with officials in whom the rank and file had no faith. Under the circumstances the loss of the strike, the breaking up of the hard-won organization, and the surrendering of the industry to the “open-shopper” was a foregone conclusion. It is one of the greatest tragedies in American labor history.

The cause of the packinghouse workers’ defeat was a double one; incompetency and treachery by the officials of the basic union in the industry, the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen, and utter failure of the rebel elements among the workers to organize themselves and thus to exercise control over the administration of their union. These fatal factors had been constantly at work ever since the packinghouse workers began their last great effort at organization in 1917. The story of the ill-fated packinghouse movement is one that Organized Labor should take well to heart:

No body of workers in American industry have been more bitterly exploited or have made more desperate efforts to escape from their slavery than the packinghouse workers. As early as 1886 they built up trade unions and established the eight-hour day. But the wily and powerful packers soon smashed their organizations and made themselves uncontested masters of the situation. The next important movement of the workers took place fifteen years later, and resulted in quite thorough organization. But again their unions were wiped out, this time in the big national strike of 1904. Then followed a thirteen-year period of unrelieved slavery and exploitation, a period in which the industry turned out a little group of enormously wealthy parasitic idlers on the one hand, and a vast multitude of impoverished and downtrodden workers on the other. All efforts to re-organize the unions were defeated. It was not until 1917 that the packinghouse workers, responding to the hope that springs eternal, again take courage and raise their heads. Taking advantage of the war conditions, they struck in Denver, Kansas City, and Omaha, achieving some little success in each place. But the real movement among them did not begin until the Chicago Federation of Labor began its big campaign to organize the workers employed in the packinghouses of Chicago.

Organization of the Industry

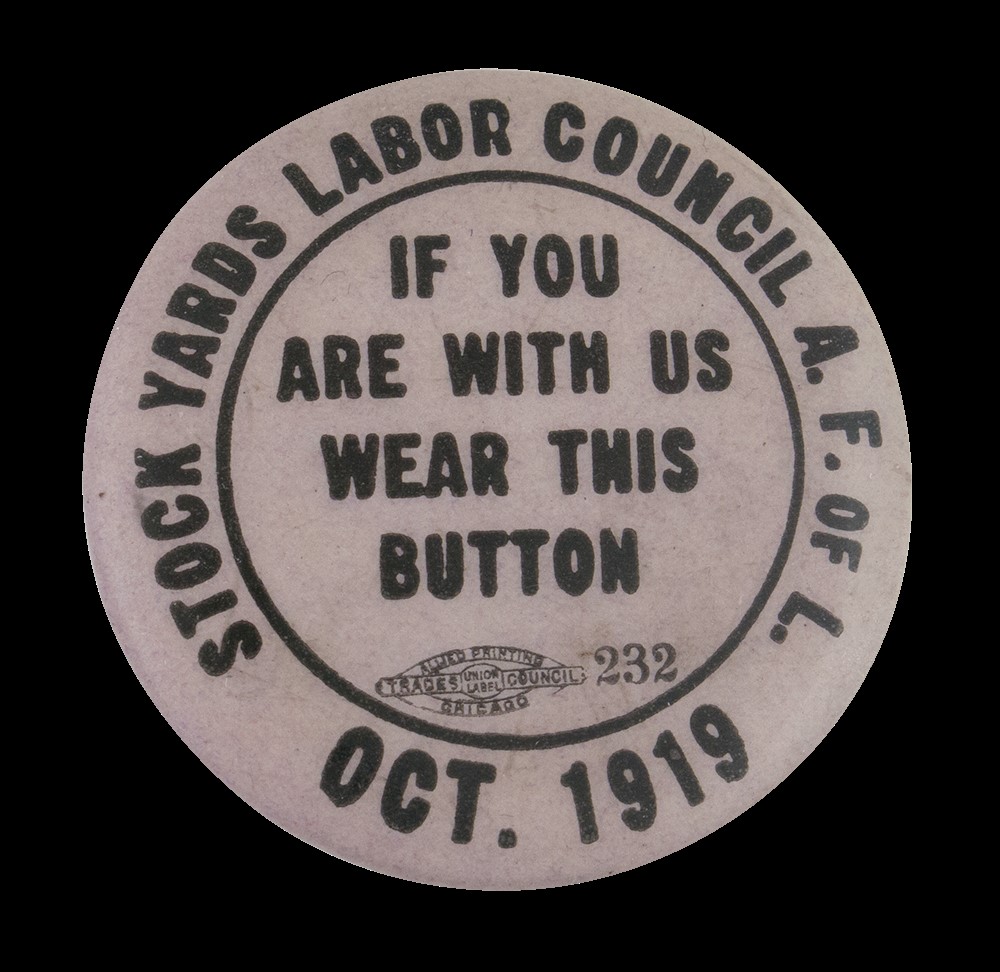

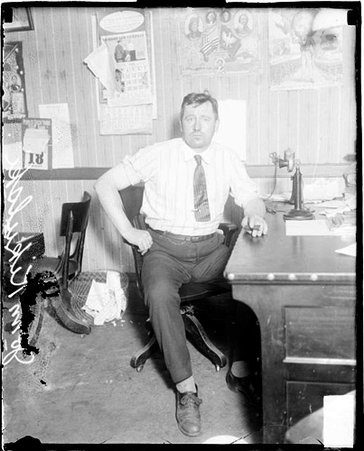

The initiative to the Chicago campaign was given by Wm. Z. Foster, who presented a resolution to the Chicago Federation of Labor calling for a joint organization movement on the part of all the trades with jurisdiction over packinghouse workers. This project was adopted on July 15th, 1917, and the Federation at once took serious hold of the situation. It organized the Stockyards Labor Council to carry on the work. John Fitzpatrick was selected to head this body during the organization work, and Foster was made its secretary.

Ever since the great strike of 1904 sporadic efforts had been made to re-organize the packinghouse workers, but without a particle of success. When the big Chicago campaign started the Amalgamated Butcher Workmen had only a handful of members, and the whole industry was demoralized. The prime cause of this failure was low grade leadership. The men at the head of the unions, the other crafts as well as the Butcher Workmmen, persistently attempted to apply outworn principles of craft unionism to this great basic industry, when the only hope of the workers was the most complete industrial solidarity. During the thirteen black years of unorganization, craft after craft made individual efforts to organize, but to no purpose whatever. First it would be the cattle butchers; they would carry on a bit of a campaign and get a few hundred members assembled, when, lo, the packers would turn their tremendous organization against them and crush their budding union as a giant would an eggshell. Then stagnation would reign a while more, until eventually, probably a straggling movement would develop among the sheep butchers, the hog butchers, the steamfitters, the engineers, or some other trade, which in turn would go the same way. In this manner practically every trade got its licking, yet the union heads never learned the lesson from this experience. They could not see that the only possibility for the packinghouse workers to make headway against the powerful packers was through absolutely united action along the lines of the whole industry.

But if the Butcher Workmen and other craft union officials knew nothing of industrial solidarity, the men who organized the Stockyards Labor Council did. The breath of life of that organization was unified action by all packinghouse workers. Before it was organized an agreement was secured from all the trades that they would cast in their lot together, and that especially they would not make the mistake they made in 1904, when they had two local councils in the Chicago stockyards, one for the mechanical trades and the other for the packing trades. The jealousies and quarrels between these two councils, resulting finally in one scabbing upon the other, was a prime factor in the loss of the great strike of 1904.

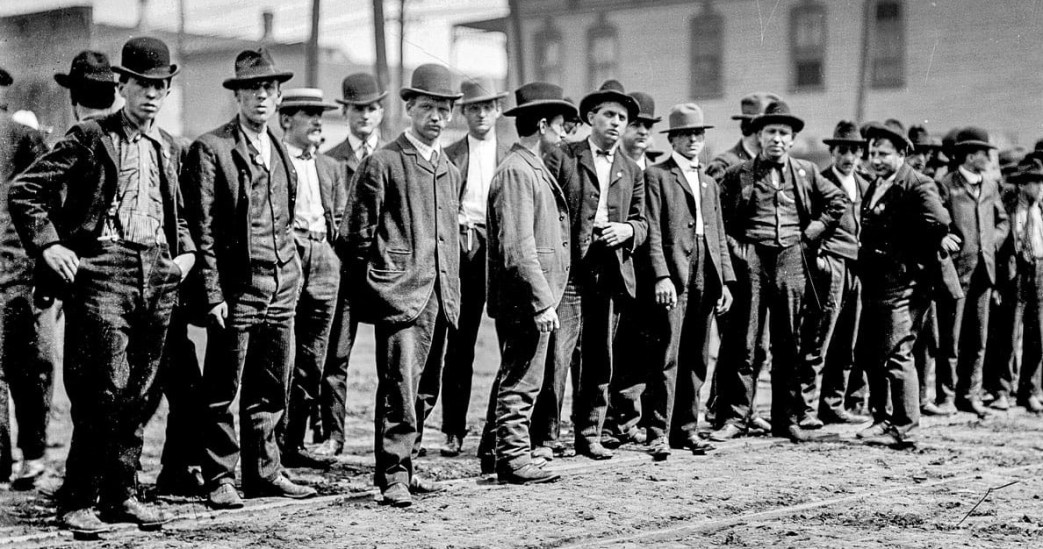

The Stockyards Labor Council organizers were determined that no such blunder should be made in the future. They raised the slogan of solidarity of all trades in the packing industry. With this rallying cry they went forth among the packers and put on one of the most aggressive campaigns of organization known to American labor history. Encouraged by the new program, the oppressed stockyards slaves responded en masse. They poured into the unions by thousands and soon the Chicago industry, then employing 55,000 workers, was strongly organized. The news of this achievement spread like wildfire in every packing center in the country, and soon the whole body of packinghouse workers everywhere were swarming into the organizations. The packing industry, long the despair of Organized Labor, was finally unionized. The whole job took but a few months.

An Incompetent Officialdom

During these stirring events the officials of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen, the union which controls about 80% of the workers in the industry, were like feathers in a gale. They did not know what it was all about. Such a slashing campaign of unionism was altogether beyond their ken Petty labor politicians, their practical conception of their union was as an organization of a few thousand meat cutters in retail butcher shops. They had no hope or understanding of organizing the packinghouse workers proper. They practically abandoned the leadership of the movement to John Fitzpatrick, Wm. Z. Foster, J.W. Johnstone, and the other men at the head of the Stockyards Labor Council. They floundered about while the latter organized the industry for them.

Realizing that the problem of the packinghouse workers was a national one and had to be so handled, the Stockyards Labor Council organizers, once their own men were fairly well lined up, initiated a movement for the establishment of an agreement with the packers to cover the whole industry. Reluctantly this was rubber-stamped by the Butcher Workmen officials. Accordingly, the local agreement between the twelve trades in the Chicago packing industry was expanded into a national one and a general committee set up to conduct the fight for the whole country. John Fitzpatrick was made chairman of this national packinghouse committee, and Foster its Secretary. As usual, the Butcher Workmen officials sat the side lines, expressing agreement with what being done, but taking little part in it. Demands were submitted and, after a spectacular arbitration proceeding conducted by Frank P. Walsh, a settlement secured covering the whole industry.

What had happened from July 15th, 1917, when the Chicago campaign began, until March 30th, 1918, when Judge Alschuler handed down his findings in the arbitration proceedings, was that the packing industry had been organized all over the country; the eight hour day established, heavy wage increases secured; the forty-hour per week guarantee introduced, and other important improvements in the workers’ conditions instituted. Besides this, the Butcher Workmen’s Union had been lifted from poverty and insignificance to affluence and power. When the Chicago campaign started this organization had only a few thousand members and was so poor that it did not contribute a single nickel in money to the campaign until after hundreds of dollars had been turned over to it in membership fees–the Chicago Federation of Labor underwrote entirely, to the last penny, the cost of the early work. But when the national drive was finished, the Butcher Workmen were a rapidly growing organization of 150,000 or more, and possessed of a large treasury. Such were the results in the packing industry by the application of industrial solidarity. The mass of workers were set squarely on their feet and given a weapon with which they could protect themselves from the packers.

A Treacherous Officialdom

It is no detraction from the work done by organizers in other centers to say that the brunt of the struggle was borne by the Stockyards Labor Council. It planned the campaign, conceived the method of organization, and to a very large extent carried it through to success. Considering what is had done for their organization, one might think that the officials of the Amalgamated Meat Cutters and Butcher Workmen would have greatly valued the Stockyards Labor Council. But the fact was exactly the contrary. From the very beginning they looked askance at it. They had no sympathy with its militancy or its doctrine of all-inclusive solidarity. They were craft unionists pure and simple. They stood aside and let it organize the industry for them, but immediately this was done they set about destroying it. Indeed, so eager was the President of the Butcher Workmen, one John Hart, to break it up that just as the national movement was developing he double-crossed all the other trades by secretly sneaking off to Washington and placing the entire matter in the tender care of the Food Administration. This nearly wrecked the whole movement. It was saved only by the Stockyards Labor Council forcing Hart to back out of his arrangement with the Washington politicians and to leave the negotiations altogether in the hands of the combined union again.

Immediately Judge lschuler’s decision was made in the arbitration matter the national officials declared open war upon the Stockyards Labor Council. Their chosen way to destroy it was by the organization of a district council of Butcher Workmen locals.

They knew very well that the establishment of such a body would pull all their unions out of the Stockyards Labor Council and leave the latter only a shell. It would create a repetition of the dualism that had ruined the packinghouse workers’ organization in 1904. But little that worried them. They went ahead with their project regardless of consequences.

The forming of the new packing trades council was in direct violation of the agreement between the Butcher Workmen and the other trades in the movement. From the inception of the campaign it had been definitely settled that there should be only one local council in the Chicago Packing industry and that it should include all trades. In fact, this was the very heart of the propaganda used to re-inspire and re-organize the workers. They had been definitely promised that the great mistake of 1904 would not be repeated, and that, sink or swim, the whole body of packinghouse workers would fight in one unit. They were violently in favor of the Stockyards Labor Council and violently against the newly-proposed packing trades council, known as District No. 9.

The Stockyards Labor Council Destroyed

The technical excuse offered by the Butcher Workmen officials was that the provisions of their constitution demanded it. But this was a mere subterfuge. Their delegates three-fourths majority in the Stockyards Labor Council and could have done as they liked with that body. Had the Butcher Workmen officials been interested in maintaining an organization in the packing houses (which in my judgment they were not) they could easily have postponed the matter until their national convention and there made an arrangement that could take care of the situation. The plain fact of the matter is that so long as the Stockyards Labor Council served their immediate ends by swarming thousands of men into their union and vast sums of money into their coffers, they had no trouble to go along with it. But just as soon as they thought they were strong enough, as soon as they felt that they had the situation well in hand, they conveniently discovered insurmountable constitutional objections to its going on as before. Then they stabbed it to death.

Even though the veriest tyro in the movement could see from the sentiment of the workers that to break up the Stockyards Labor Council meant to smash the whole packing house movement, the officials of the Butcher Workmen nevertheless went blithely ahead with the nefarious task. To further their project they sent a flock of “organizers” into the stockyards district to prepare the way for the new council. These sowed the seeds of disruption thickly, undermining the whole structure of the movement. Several ineffectual attempts were made to start the new council, but they all failed as the sentiment of the workers was overwhelmingly in favor of the Stockyards Labor Council. Finally, however, in July 1919, enough dupes were scared up to form the fatal District No. 9, and it was duly established.

Internal Warfare and Disruption

Immediately turmoil raged among the packinghouse workers, who looked upon these effort to split their ranks as the work of the packers. They refused point blank to affiliate with District No. 9, in spite of the fulminations of their national officials. Of 40,000 organized workers not more than 2,000 joined the new body. Then the national office of the Butcher Workmen carried its work of destruction still further by suspending all the locals that refused to accept their dual council. This meant confusion worse confounded. Thousands quit the unions disgusted, feeling that they had been betrayed. Others entered militantly into the many bitter factional quarrels that had been started among the workers by the irresponsible national officials.

Soon the disruptive work of the latter bore its full fruit, soon the former splendid solidarity of the workers was destroyed. Instead of the one unified council that carried the big battle through, they now had three: the emasculated Stockyards Labor Council, District No. 9, and a Mechanical Trades Council. In addition there were a number of independent unions disgusted with all these bodies, and affiliated with none of them. The work of disruption was complete. The officers of the Butcher Workmen had done the Chicago movement to death, and with it the movement all over the country, for it is a truism that the status of the packinghouse unions everywhere depends directly upon the degree of organization prevailing in Chicago, the heart of the industry. After the installation of District No. 9 the fate of the union was sealed. Its course thereafter was rapidly downward. It was only a matter of time until the packers should deliver a coup de grace which finally came in the recent strike.

As Usual, the Rebels Sleep

Considering the type of men at the head of the Butcher Workmen’s Union, the only possible hope for the great movement to succeed was for the live spirits among the rank and file to take the situation well in hand and force their international officials into line or out of office. This was evident from the start, and it became more evident as the movement wore on. For a time the live wires handling the Stockyards Labor Council were able to hold the reactionary national officials to something like a real program. But as the latter became more and more intrenched by the stabilizing of the union everywhere and the extension of their machine, the spreading of the rank and file movement to a national scale became imperative to prevent the general officials from wrecking the movement through their stupid methods–to put it charitably.

The burden of organizing this rank and file movement fell upon J.W. Johnstone–before the bitter struggle really got started Fitzpatrick and Foster, the first president and secretary of the Stockyards Labor Council, had withdrawn from the movement to take up other duties. Johnstone was the new secretary of the Stockyards Labor Council and an experienced man in the labor movement. He knew what had to be done and he tried to do it. When the national officials set out to wreck the old council Johnstone undertook to organize the rebels everywhere against them. He and his associates published an independent paper, The Packinghouse Worker, and scattered it broadcast over the industry to counteract the lies spread by the national office. Efforts were made everywhere to line up the fighting elements in the unions.

But unfortunately this work failed completely. The rebels were simply not to be roused. They were still heavily afflicted with the “infantile sickness” of dual unionism and could not be induced to take an active part in the fight against the reactionaries. In Chicago and other cities Johnstone appeared before numerous radical groups existing among the packinghouse workers and fairly begged them to come in to the struggle. But in each case all he got was a cold shoulder. The radicals, save for a few notable exceptions, would have nothing to do with the trade unions. They preferred to spend their time in contemplation of their beautiful industrial utopias. The cold hard facts of the mass struggle were far from them.

The Rebels Primarily Responsible

Here we come to the crux of the trouble. The real fault for the failure of the packinghouse movement lies with the rebel elements in the industry, and they are many, as the body of workers are foreigners. Hart, Lane, and the others who held control of the Butcher Workmen’s organization during the critical days were typical craft unionists and therefore altogether unfit to make headway against modern combinations of capital. It would be stupid to expect them to follow any other course than the ruinous one they did, save under pressure. A leopard cannot change his spots. If the movement was to live and prosper the impetus thereto had to come up from below, from an aroused and organized rank and file.

But this impetus did not come. The radicals, the only ones who could develop it, were asleep at the switch. Here was a great movement going begging for them to control it. The enormous organizations in Chicago were in the hands of the minute group of radicals who did show enough understanding to take part in the movement. And it would have been an easy thing to have secured similar control in other places, had the radical elements only been willing to assume such control. Sufficient resistance, at least, could have been developed to prevent the national officials from wrecking the union. But no, the radicals stood aside, callously indifferent, and allowed the organization to be cut to pieces by the reactionaries. The loss of the packinghouse movement is just one more item, and a terrible one, that must be added to the heavy price the trade union movement is paying for the dualistic notions which have destroyed the power and influence of those workers who should be its best and livest elements.

Down the Toboggan

After the wrecking of the Stockyards Labor Council the downfall of the organization was rapid. Thousands quit the trade unions in disgust. Soon the national officials broke the front of the 35,000 members of the outstanding locals by winning over one John Kikulski, an influential Polish organizer who was later killed by some of his many enemies. Kikulski’s desertion disrupted the rebel ranks. Many went back with him to the Butcher Workmen, and thousands gave up their affiliation altogether. And what was happening in Chicago was pretty much happening in all the other packing centers. Mismanagement, if not worse, by the Butcher Workmen officials, throttled the organization everywhere.

By the Spring of 1921 the organization was virtually a wreck all over the country. So much so that the packers, freshly freed from the war-time control agreement administered by Judge Alschuler, determined to put it out of business altogether. But with a flash of the old spirit the workers rallied again in wonderful form. Enormous mass meetings took place and the unions grew like weeds. Quite evidently the workers were decided to put up a bitter fight. But again their officials failed them. They meekly accepted the proposed wage cuts and allowed the establishment of the company unions. Once more the organization began to disintegrate rapidly.

Things went from bad to worse until the packers announced their next heavy wage cut, a few months ago. The organization had almost bled to death. Yet the workers responded again, this time more weakly. A strike ballot was taken. This carried affirmatively in a small vote, and finally a strike date was set for December 5th. Then a marvel happened: When the strike was called few expected that any considerable numbers of the discouraged and disappointed workers would walk out. But when the fateful day arrived they turned out en masse everywhere, hamstringing the whole packing industry. In Chicago it was estimated that fully 75% of the actual workers struck, and in other centers the percentage was even higher. A few of the craft unions, notably the engineers, stockhandlers, etc. who had been thoroughly alienated by the Butcher Workmen officials, refused to strike. But nevertheless the strike was quite general. Considering the circumstances, the organized treachery and mismanagement that the workers had suffered from in their unions for years, it was a noble display of solidarity. But it was futile, it was only the dying agony of the organization. There was not a possibility for success. There was neither competent leadership among the rank and file nor among the Butcher Workmen officials. All the packers had to do was to sit tight for a while and wait for the inevitable collapse. This they did, refusing all efforts at settlement. On January 31st the great break came. The Butcher Workmen called off the hopeless strike. The packinghouse movement was crushed, broken by the combined mismanagement of its official leaders and the indifference of the rebel elements in the industry.

As to the Future

What the future has to offer for the packinghouse workers in the way of organization is problematical. After such a crushing defeat, following in the train of so much betrayal and mismanagement by their officials, it is safe to say that they will be seized by profound demoralization and depression. Already the dual unions are gathering to feed upon the corpse of the fallen giant and to add to the general confusion. They have nothing to offer, in spite of their glowing programs. The only hopeful factor in the situation is the changed views of many radicals in the industry. Within the last few months (although too late to appreciably affect the dying movement) they have come to see that it is their part to stay in the old unions and to so organize themselves there as to compel the proper handling of the organization, no matter who may stand at its head. Had they understood this fact three or four years ago and taken charge of the packinghouse movement when it lay wide open before them, the whole history of it would have been different. Instead of being crushed and defeated as they now are, the packinghouse workers would still possess a powerful and well-intrenched trade union organization.

It is never too late to mend. The rebels in the packing industry must set out at once to break the power of the reactionaries at the head of their organization. They must see to it that when the next big drive comes, and it is only a matter of time, the men who conduct it are real working class fighters and not mere place-hunters and incompetent bureaucrats. In that direction alone lies the possibility for success.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

Link to PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v1n01-mar-1922-color.pdf