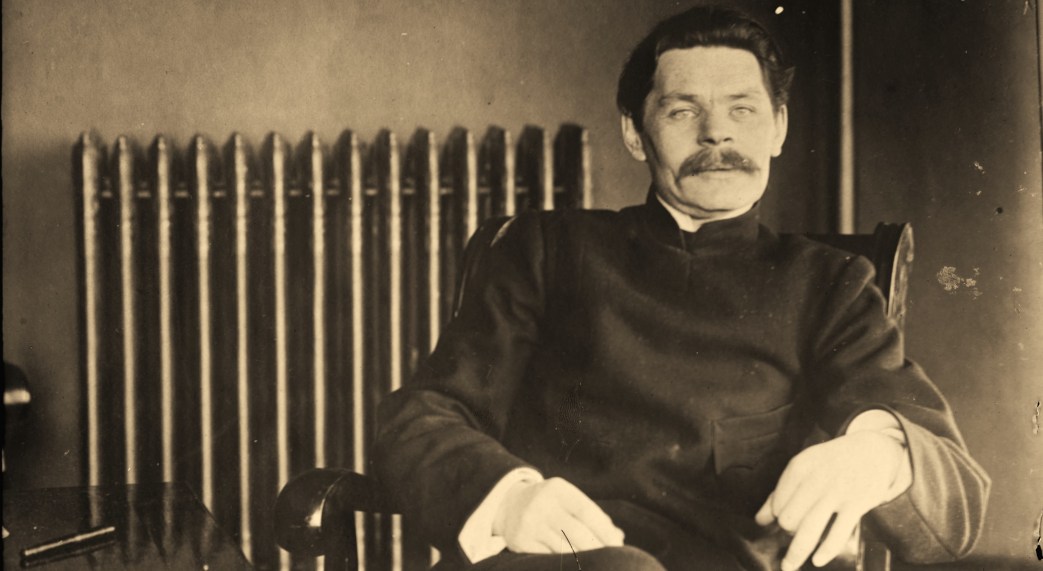

Maxim Gorky visited the United States in 1906 on a fund-raising and agitational tour for the R.S.D.L.P. and wrote his impressions of U.S. society with this brilliant and incisive essay on New York City, the City of Mammon.

‘The City of Mammon’ by Maxim Gorky from The Worker (New York). Vol. 16 No. 17. August 4, 1906.

A gray mist hung over land and sea, and a fine rain shivered down upon the sombre buildings of the city and the turbid waters of the bay. The emigrants gathered to one side of the steamer. They looked about silently and seriously, with eager eyes in which gleamed hope and fear, terror and joy.

“Who is this?” asked a Polish girl in a tone of amazement, pointing to the Statue of Liberty. Someone from the crowd answered briefly: “The American Goddess”.

I looked at this goddess with the feeling of an idolator. Before my memory flashed the brilliant-names of Thomas Jefferson and of Grant.

“The land of liberty!” I repeated to myself, not noticing on that glorious day the green rust on the dark bronze.

I knew even then that “The War for the Abolition of Slavery” is now called in America “The War for the Preservation of the Union”. But I did not know that in this change of words was hidden a deep meaning, that the passionate idealism of the young democracy had also become covered with rust, like the bronze statute, eating away the soul with the corrosive of commercialism. The senseless craving for money, and the shameful craving for the power that money gives, is a disease from which people suffer everywhere. But I did not realize that this dread disease had assumed such proportions in America.

The Treadmill of Toil

The tempestuous turmoil of life on the water at the foot of the Statue of Liberty, and in the city on the shore, staggers the mind and fills one with a sense of impotence. Everywhere, like antediluvian monsters, huge, heavy steamers plough the waters of the ocean, little boats and cutters sentry about like hungry birds of prey. The iron seems endowed with nerves, life and consciousness.

And it seems as if all the iron, all the stones the wood and water, and even the people themselves are full of protest against this life in the fog, this life devoid of sun, song, and joy, this life in the captivity of hard toll. Everywhere is toll, everything is caught up in its whirlwind, everybody obeys the will of some mysterious power hostile to man and to nature. A machine, a cold, unseen, unreasoning machine, in which man is but an insignificant screw!

I love energy. I adore it. But not when men expend this creative force of theirs for their own destruction. There is too much labor and effort and no life in all this chaos, in all this bustle for the sake of a piece of bread. Everywhere we see around us the work of the mind which has made of human life a sort of hell, a senseless treadmill of labor, but nowhere do we feel the beauty of free creation, the disinterested work of the spirit which beautifies life with imperishable flowers of life-giving cheer.

Independence a Phantom

Far out on the shore, silent and dark “skyscrapers” are outlined against the fog. Rectangular, with no desire to be beautiful, these dull, heavy piles rise up into the sky, stern, cheerless, and morose. In the windows of these prisons there are no flowers, and no children are anywhere seen. These structures elevate the price of land to heights as lofty as their tops, but debase the taste to depths as low as their foundations. It is always so. In great houses dwell small people.

From afar the city looks like a huge jaw with black, uneven teeth. It belches forth clouds of smoke into the sky and sniffs like a glutton suffering from overcorpulency. When you enter It you feel that you have fallen into a stomach of brick and iron which swallows up millions of people, and churns, grinds, and digests them.

The people walk along the pavements. They push hurriedly forward, all hastily driven by the same force that enslaves them. But their faces are calm, their hearts do not feel the misfortune of being slaves; indeed, by a tragic self-conceit, they yet feel themselves its masters. In their eyes gleams a consciousness of independence, but they do not know it is but the sorry independence of the axe in the hands of the woodsman, of the hammer in the hands of the blacksmith. This liberty is the tool in the hands of the Yellow Devil–Gold. Inner freedom, freedom of the heart and soul, is not seen in their energetic countenances. This energy without liberty is like the glitter of a new knife which has not yet had time to be dulled; it is like the gloss of a new rope.

Unhappy New York

It is the first time that I have seen such a huge city monster: nowhere have the people appeared to me so unfortunate, so thoroly enslaved to life as in New York. And furthermore nowhere have I seen them so tragicomically self-satisfied as in this huge phantasmagoria of stone, iron, and glass, this product of the sick and wasted imagination of Mercury and Pluto. And looking upon this life, I began to think that in the hand of the statue of Bartholdi there blazes not the torch of liberty, but the dollar. The large number of monuments in the city parks testifies to the pride which its inhabitants take in their great men. These statues covered with a veil of dirt involuntarily force one to put a low estimate upon the gratitude felt by the Americans toward all those who lived and died for the good of their country. The mammoth fortunes of Morgan and Rockefeller wipe oft from memory the significance of the creators of liberty–Lincoln and Washington.

“This is a new library they are building,” said someone to me, pointing to an unfinished structure sur rounded by a park. And he added importantly: “It will cost $2,000,000. The shelves will measure 150 miles.”

Another gentleman told me, as he pointed out a painting to me: “It is worth $500.”

That Theatrical Trust

I meet here very few people who have a clear conception of the intrinsic worth of art, its religious significance, the power of its influence upon life, and its indispensableness to mankind. It seems to me that what is superlatively lacking in America Is a desire for beauty, a thirst for those pleasures which it alone can give to the mind and to the heart. Our earth is the heart of the universe, our art the heart of the earth. The stronger it beats the more beautiful is life. In America the heart beats feebly.

I was both surprised and pained to find that in America the theaters were in the hands of a trust, and that the men of the trust, being the possessors, had also become the dictators in matters of the drama. This evidently explains the fact that a country which has excellent novelists has not produced a single eminent dramatist.

To turn art into a means of profit is under all circumstances a serious misdemeanor, but in this particular case it is a positive crime, because it offers violence to the author’s person, and adulterates art.

The theater is called the people’s school; It teaches us to feel and to think.

But perhaps the Americans think that they are cultured enough? If so, they are easily in error.

A Lack of Culture

The first evidence of the absence of culture in the American is the interest he takes in all stories and spectacles of cruelty. To a cultured man, a humanist, blood is loathsome. Murder by execution and other abominations of a like character arouse his disgust. In America such things call forth only curiosity. The newspapers are filled with detailed descriptions of murders and all kinds of horrors. The tone of the description is cold, the hard tone of an attentive observer. It is evident that the aim is to tickle the weary nerves of the reader with sharp, pungent details of crime, and no attempt is ever made to explain the social basis of the facts.

To no one seems to occur the simple thought that a nation is a family. And if some of its members are criminals. It only signifies that the system of bringing up the people in that family is badly managed.

I will not dwell on the question of the attitude of the white man toward the negro. But it is very characteristic of the American psychology that Booker T. Washington preaches the following sermon to his race:

“You ought to be as rich and as clean outwardly as the whites; only then will they recognize you as their equals.” This, in fact, is the substance of his teachings to his people.

But in America they only think of how to make money. Poor country, whose people are occupied only with the thought of how to get rich!

I am never the least dazzled by the amount of money a man possesses; but his lack of honor, of love for his country, and of concern for its welfare always ails me with sadness. A man milking his country like a cow, or battening on it like a parasite, is a sorry sort of inspiration. How pitiful that America, which they say has full political liberty, is utterly wanting in liberty of spirit! When you see with what profound interest and idolatry the millionaires are regarded here you involuntarily begin to suspect the democracy of the country. Democracy–and so many kings; democracy and a “higher society”. All this is strange and incomprehensible.

All the numerous trusts and syndicates, developing with a rapidity and energy possible only in America, will ultimately call forth to life its enemy, revolutionary Socialism, which in turn will develop as rapidly and as energetically. But while the process of swallowing up individuals by capital, and of the organization of the masses is going on, capitalism will spoil many stomachs and heads, many hearts and minds.

Speaking of the national spirit. I must also speak of the morality of the nation. That side of life has always been a poser to me. I cannot understand it; and when people speak seriously about it I cannot help but smile. At best, a moralist to me is a man at whom I wink from the corner of my eye, and drawing him aside whisper in his ear: “Ah, you rascal! It isn’t that I am a sceptic, but I know the world, I know it to my sorrow.”

As to Morality

The most desperate moralist I have come across was my grandfather. He knew all the roads to heaven, and constantly preached about them to everyone who fell into his hands. He alone knew the truth. He knew to a dot everything that God wanted, and he used to teach even the dogs and cats how to conduct themselves in order to attain eternal happiness. But, with all that, he was greedy and malicious–he beat his domestics on every spare and suitable occasion with whatsoever and howsoever he desired.

I tried to influence my grandfather, wishing to make him milder. Once I threw the old man out of the window, another time I struck him with a looking glass. The window and the looking glass broke, but grandpa did not get any better. He died a moralist.

Since that time I regard all discourses on morality as a useless waste of time. And, moreover, being from my youth up a professional sinner, like all honest writers, what can I say about morality? I wish it to be understood that in thus speaking of moralists I do not mean those who think, but only those who judge. Emerson was a moralist, but I cannot imagine a man who, having read Emerson, will not have his mind cleared of the dust and dirt of worldly prejudices.

Man is by nature curious. I have more than once lifted the lid of the moral vessel and every time there issued from it such a rank, stifling smell of lies and hypocrisy, cowardice and wickedness, as was quite beyond the power of my nostrils to endure.

I am willing to think that the Americans are the best moralists in the world, and that even my grandpa was a child in comparison. I admit that nowhere else in the world are there to be found such stern priests of ethics and morality, and, therefore, I leave them alone. But a word about the practical side. America prides itself on its morals, and occasionally constitutes itself as judge, evidently presuming that it has worked out in its social relations a system of conduct worthy of imitation. I believe this is a mistake.

The Americans run the risk of making themselves ridiculous if they begin to pride themselves on their society. There is nothing whatever original about it; the depravity of the “higher classes of society” is a common thing in Europe. If the Americans permit the development of a “higher society” in their country, there is nothing remarkable in the fact that depravity also grows apace. And that no week passes without some loud scandal in this “high society” is no cause for pride in the originality of American morals. You can find all these things in Europe also.

I must yet mention the fact that in America they steal money very frequently and lots of it. This, of course, is but natural. Where there is a great deal of money there are a great many thieves. To imagine a thief without money is as difficult as to imagine an honest man with money. But that again is a phenomenon common to all countries.

A magnificent Broadway, but a horrible east side. What an irreconcilable contradiction, what a tragedy! The street of wealth must perforce give rise to harsh and stern laws devised by the financial aristocracy, by the slaves of the yellow devil, for a war upon poverty and the Whitechapel of New York. The poverty and the vice of the East Side must perforce breed anarchy. I do not speak of a theory. I speak of the development of envy, malice, and vengeance, of that, in a word, which degrades man to the level of an anti-social being. These two irreconcilable currents, the psychology of the rich and the feeling of the poor, threaten a clash which will lead to a whole series of tragedies and catastrophes.

America is possessed of a great store of energy, and therefore everything in it, the good and the bad, develops with greater rapidity than anywhere else. The children in the streets of New York produce a profoundly sad impression. Playing ball and the crash and thunder of iron, amid the chaos of the tumultuous city, they seem like flowers thrown by some rude and cruel hand into the dust and dirt of the pavements. The whole day long they inhale the vapors of the monstrous city, the metropolis of the Yellow Devil. Pity for their little lungs, pity for their eyes choked up with dust!

The People’s Awakening

I have seen poverty a-plenty and know well her green, bloodless, haggard countenance. But the horror of East Side poverty is sadder than everything that I have known. Children pick out from garbage boxes on the curbstones pieces of rotten bread and devour it, together with the mold and the dirt, there in the street in the stinging dust and the choking air. They fight for it like little dogs. At midnight and later they are still rolling in the dust and the dirt of the street, these living rebukes to wealth, these melancholy blossoms of poverty. What sort of a fluid runs in their veins? What must be the chemical structure of their brains? Their lungs are like rags fed upon dirt, their little stomachs like the garbage boxes from which they obtain their food. What sort of men can grow up out of these children of hunger and penury? What citizens?

America, you who astound the world with your millionaires, look first to the children on the East Side and consider the menace they hold out to you! The boast of riches when there is an East Side is a stupid boast. However, “there is no evil without a good”, as they say in Russia, country of optimists.

This life of gold accumulation, this idolatry of money, this horrible worship of the Golden Devil already begins to stir up protest in the country. The odious life, entangled in a network of iron and oppressing the soul with its dismal emptiness, arouses the disgust of healthy people, and they are beginning to seek for a means of rescue from spiritual death.

And so we see millionaires and clergymen declaring themselves Socialists, and publishing newspapers and periodicals for the propaganda of Socialism. The creation of “settlements” by the rich intellectuals, their abandonment of the luxury of their parental homes for the wilds of the East Side–all this is evidence of an awakening spirit; it heralds the gradual rise in America of the human life. Little by little people begin to understand that the slavery of gold and the slavery of poverty are both equally destructive.

The important thing is that the people have begun to think.

After all that I have said, I am involuntarily drawn to make a parallel between Europe and America. On that side of the ocean there is much beauty, much liberty of the spirit, and a bold, vehement activity of the mind. There art always shines like the sky at night with the living sparkle of the imperishable stars. On this side there is no beauty. The rude vigor of political and social youth is fettered by the rusty chains of the old Puritan morality bound to the decayed fragments of dead prejudices.

Europe shows evidence of moral decrepitude, and, as a consequence of this, skepticism. She has suffered much. Her spiritual suffering has produced an aristocratic apathy, It has made her long for peace and quiet.

America has not yet suffered the pangs of the dissatisfied spirit, she has not yet felt the aches of the mind. Discontent has but just begun here. And it seems to me that when America will turn her energy to the quest of liberty of the spirit, the world will witness the spectacle of a great conflagration, a conflagration which will cleanse this country from the dirt of gold, and from the dust of prejudice, and it will shine like a magnificent cut diamond, reflecting in its great heart all the thought of the world, all the beauty of life.

The Worker, and its predecessor The People, emerged from the 1899 split in the Socialist Labor Party of America led by Henry Slobodin and Morris Hillquit, who published their own edition of the SLP’s paper in Springfield, Massachusetts. Their ‘The People’ had the same banner, format, and numbering as their rival De Leon’s. The new group emerged as the Social Democratic Party and with a Chicago group of the same name these two Social Democratic Parties would become the Socialist Party of America at a 1901 conference. That same year the paper’s name was changed from The People to The Worker with publishing moved to New York City. The Worker continued as a weekly until December 1908 when it was folded into the socialist daily, The New York Call.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/the-people-the-worker/060804-worker-v16n18.pdf