The full text of Frank Spector’s pamphlet, written in prison, on the multi-racial lettuce workers strike and defense led by T.U.U.L. affiliate, the Agricultural Workers Industrial League (which later became the Cannery and Agricultural Workers’ Industrial Union) in California’s Imperial Valley during 1930. While a defeat, the strike was a milestone in farm worker organizing, particularly important to the Filipino workers’ movement.

‘The Story of the Imperial Valley’ by Frank Spector. I.L.D. Pamphlets No. 3. International Labor Defense, New York. 1931.

The Raid on En Centro

ON the night of April 14, 1930, over one hundred Mexican, Filipino, Negro and white workers gathered in a dingy working class hall in El Centro, the largest city of the Imperial Valley, in California. They had been called there by the Agricultural Workers Industrial Union to discuss their conditions and to prepare to participate, a week later, in a conference of delegates from ranches and sheds. The conference was to weld the ranks of the workers for the coming strike against inhuman exploitation, the contract system, speed-up, and unemployment.

One after another the workers stood up and spoke, each in his own tongue. They told of the starvation and sickness of their wives and children, of the constant wage cuts, and of the long hours of bitter toil under a scorching sun. Each one spoke of the readiness of the workers to fight under their union’s militant guidance.

Suddenly the door burst open. Into the hall rushed a mob of policemen, deputy sheriffs and civilians–all armed with revolvers and sawedoff shotguns which they trained upon the assembled workers.

Out of this mob stepped Sheriff Gillette, the chief gunman of the Imperial Valley bosses. Ordering all workers to throw up their hands, he then directed a violent search of each worker, after which every one of the 108 were chained in groups. Then the mob, with a brutal display of force, threw them into huge trucks. The entire one hundred and eight were hauled into El Centro under heavy guard and thrown into the county jail there.

Two months passed. A number of the group, who were Mexican workers, were deported. A number were released.

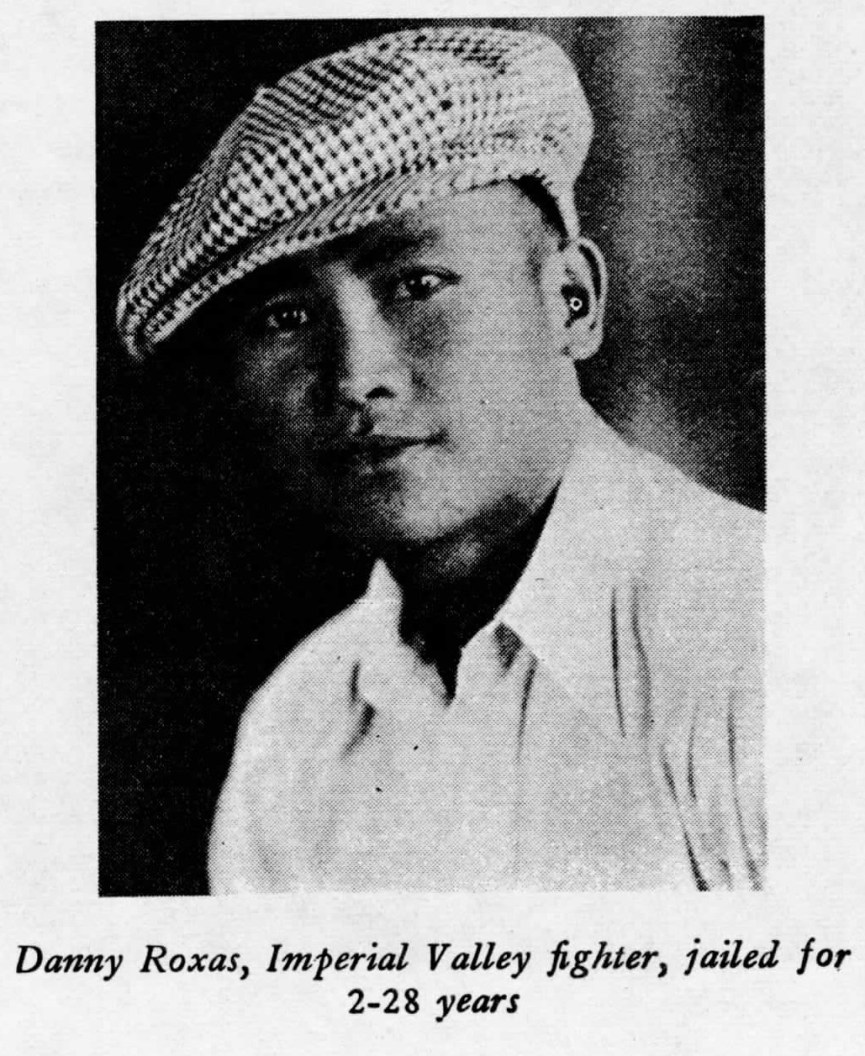

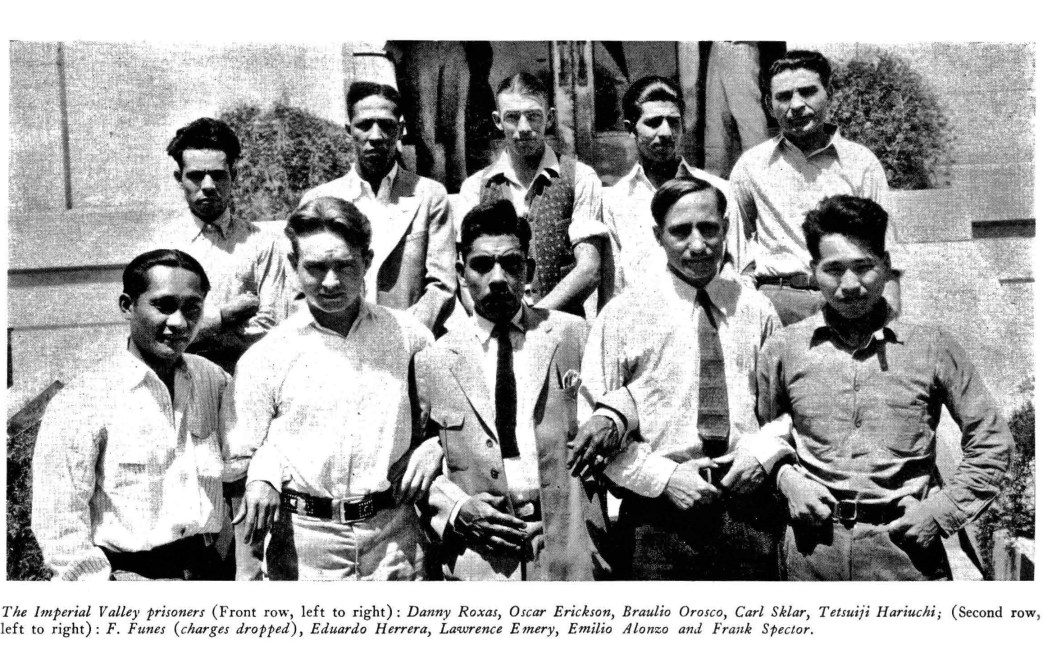

Today, Carl Sklar, organizer, Los Angeles section of the Communist Party, and Tetsuji Horiuchi, Japanese worker and Trade Union Unity League organizer, are serving three to forty-two years in Folsom State Prison. Oscar Erickson, National Secretary of the Agricultural Workers Industrial League, Lawrence Emery, of the Marine Workers Industrial Union, Frank Spector, District Organizer of the International Labor Defense, and Danny Roxas, a Filipino worker and Secretary of the Agricultural Workers Industrial League in Imperial Valley are serving three to forty-two years in San Quentin State Prison. Eduardo Herera and Braulio Orosco, both Mexican workers, are now serving two to twenty-eight years in San Quentin. Originally held for deportation, they were later ordered to jail.

The Valley–A Huge Fruit and Vegetable Factory

The Imperial Valley lies in the extreme southern part of California. Its southern end touches the border of Mexico, the chief labor source for the Valley landowners. In the spring and summer seasons the Valley is terribly hot, the temperature reaching as high as 120 degrees in the shade. The weather in winter makes the Valley a winter playground for the idle rich, who flock to the luxurious hotels of El Centro, Brawley and Calexico. Not far away is Mexicali, a Mexican border town, with its booze and gaudy resorts, always an attraction for these parasites who stage their drunken parties under the benevolent protection of the Mexican and United States grafting border officials.

The major industry of the Imperial Valley is truck-gardening on a large factory scale. The huge fields yield lettuce in January and February, cantaloupes in June and July, watermelons in July and August, as well as other minor crops.

The condition of the desert soil requires extensive irrigation, without which nothing will grow. This factor has contributed largely to the rapid squeezing out of the small-scale farmer by fruit and vegetable companies. The irrigation water is supplied from the Colorado River by the “Imperial Irrigation District,” a “stock company” holding charters on both sides of the border–Imperial County and Baja (Lower) California in Mexico. This company virtually controls the destinies of the Imperial Valley, as it holds in the palm of its hand the entire system of irrigation. This company, in turn, is under the complete control of the Western Growers’ Protective Association, as well as the American Fruit Growers, Inc. Both are dominated by Harry Chandler, the notorious Los Angeles open-shopper and owner of the vicious Los Angeles Times. He is reported to be also the owner of 1,000,000 acres of land in Baja California, Mexico.

Through a clever system of obligatory purchase of shares worked out by these powerful companies, in numbers equivalent to the acreage held by each small farmer, the latter have been almost completely crushed. Unable to cultivate his entire acreage, the small farmer used up the profits of his tilled acres to pay for the unused irrigation of his idle land. He was then forced to get rid of the acres, selling them to the big companies, at their own price. The process of squeezing out was rapidly completed by the unequal competition with the mass production methods of the big companies which use the most modern agricultural machinery and terrifically exploit and speed up the field and shed workers.

The small rancher has thus either abandoned the Valley, or has been turned into a lease-holding tenant who rents land and machinery from the big companies, making either a yearly cash payment or paying in produce a large part of the annual yield. So we now find a system of tenantry in the Valley, the absentees and owners reaping tremendous profits out of their ill-gotten holdings.

Conditions of Workers

Over ten thousand workers are engaged in harvesting the crops on the huge fruit and vegetable factory-fields. About two thousand workers man the packing and shipping sheds where the products are graded, crated and shipped.

Most of the field workers are Mexicans, from across the border. Other large groups include Filipinos, two thousand Negroes, and several hundred Hindus.

The sheds employ white workers almost exclusively, the greater number being migratory laborers. By using the most modern machinery, supplied by the large land holders to the tenants from huge “headquarter farms,” a negligible number of workers are employed to cultivate the fields.

Most of the field and shed workers are completely dependent upon the extremely short harvest seasons. This creates highly irregular working conditions. On the one hand come long periods of unemployment; On the other, feverish labor during the busy season. Because of the skill required, the shed workers are in a comparatively better position than the Mexican, Filipino and other workers in the fields. The pay of the white workers during the seasonal rush varies from sixty-five cents to one dollar an hour, with piece work prevailing. By toiling inhumanly long hours, ranging from sixteen to eighteen a day, the skilled white worker may pack at an amazing speed as high as four to five hundred crates a day. But his earnings are constantly curtailed by crates rejected by the specially employed grading inspectors.

The most bitterly exploited are the field workers. These thousands of Mexican, Filipino and Negro workers are the victims of a contract system that renders them virtual slaves to the landowners. This contract system has been so devised that it permits the big companies to reap huge profits out of the sweat and blood of the workers. Concretely, this is the way the system works:

The large land holdings are leased to tenants. These in turn, at the approach of every season, conclude contracts with “pickers,” chiefly Japanese, Mexicans or Filipinos. These pickers agree to furnish all the laborers needed to harvest the season’s crop for the tenant. The wages are usually determined by the tenant, but the pickers (or “contractors”) receive as commission a certain percentage of the worker’s wages, usually about two cents a crate.

To secure fulfilment of the contract, the tenant withholds twenty-five per cent of the contractor’s commission, who, in turn, does like wise with the workers he hires. He withholds twenty-five per cent of the workers’ earnings until the last week of the season, when the final accounts are generally settled. It is very common, however, for the workers to be victimized. The “contractor” at the end of the season may “disappear” with the accumulated twenty-five per cent of the workers’ wages, or the tenant himself may fail to pay the “contractor” under the pretext of a bad crop. Thus, the one who actually owns the big landing company is completely cleared of any blame for this trickery while always guaranteed the receipt of huge profits.

Hypocritical gestures toward preventing this robbery have been made by the State Labor Department which, in response to numerous complaints of the workers, sent a representative of the Valley during the 1928 strike. The official, however, contented himself and his superiors by submitting a lengthy report in which he conceded the evidence of this vicious contract practice, at the same time whitewashing the big companies of all blame. Needless to say, the Department of Labor has taken no steps to abolish the contract system.

This state report, however, contains illuminating admissions of the miserable conditions which exist. The International Labor Defense attorneys tried to introduce these findings as evidence, but were promptly barred by the servile judge.

The labor of the field workers is extremely hard. Toiling during the seasons from sunrise till sunset under a scorching sun with a heavy sack on his bent back, many a worker has actually dropped dead from sunstroke and sheer exhaustion. For all this they get a miserable wage of twenty-five to thirty-five cents an hour.

They are often cheated by the foreman, who alone counts the crates. The workers are not paid for forced idle hours, caused either by the dew in the morning when the products can not be picked, or by time lost when waiting in the fields for crates. During work they quench their thirst from irrigation ditches containing water unfit even for animals to drink.

Living conditions of these workers and their families are extremely wretched. They live in makeshift “company camps” from which they go daily to their jobs. The “company camps” border on the fields. Many large families, each with six to eight children, may be huddled together, either in ancient tents or in thatched shacks with brush-covered roofs. In these camps there is a total absence of elementary sanitation. Water from irrigation ditches, caked with mud, serves for drinking as well as for washing purposes. For toilets they have a ditch dug on the edge of the camp, giving off an unbearable stench. Disease and death among the children and adults are the camp-followers of the workers.

Struggles of the Workers

It is small wonder that such conditions, existing for years, have resulted in many spontaneous revolts of the Imperial Valley workers where there have been big strikes. And with the approach of almost every working season there is a rumble of protest from the workers, followed by partial walkouts at the rush hours. But the Imperial Valley masters are well prepared for these occasions. They leave no stone unturned to protect their profits. It matters nothing to them that this “protection” means the spilling of the workers’ blood and their children’s tears, for every leaf of lettuce harvested and every melon picked.

A highly efficient strike-breaking system is in operation. This embraces the most important fruit and vegetable fields of northern and southern California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas and other states. Through a special transportation agreement the Southern Pacific Railroad can, almost overnight, flood any of these sections with scab labor, herded at every point by special detective agencies in the hire of the fruit and vegetable companies.

The absence of a revolutionary class-conscious leadership and lack of correct policies had enabled the scab-herding combination of the land owners, the railroads, and the detective agencies, as well as the state, to suppress the workers’ revolts without difficulty.

Race Discrimination

Race discrimination has been fully used by the Imperial Valley bosses against the workers to prevent their organization. The recent race riots against the Filipino workers in California illustrate the results of this policy. Mobs, instigated by the bosses and their kept press, killed several Filipino workers and injured a number of others.

First rousing it, the bosses keep the fires of race-hatred constantly smouldering in the Valley. They segregate the Mexican, Filipino and Negro workers. The towns are usually divided in the center by the Southern Pacific railroad tracks. “Mexican Town,” with its ramshackle, tumbled down shanties, is completely separated from the “white” section, in the windows of the stores of which are signs reading “For White Trade Only.”

Along with this general type of race-discrimination. the bosses also sow seeds of poisonous race-hatred between the largest groups of workers–the Mexican and Filipino. They play one against the other by cutting the wages of the Mexicans and telling them that the Filipino workers have agreed to take their jobs at a few cents less. They tell the same lies to the Filipino workers. When they want to cut their wages, they tell them that the Mexicans want to work for less.

Role of the Fakers

Of the numerous strikes that have occurred in the Valley, those of 1917, 1922, 1928 and the recent strike movement of January, February and June, 1930, were the most significant both in numbers and militancy. The short strikes of 1917 and 1922 were accompanied by brutal terrorism in which the bosses’ chief henchman, Sheriff Gillette, became notorious. The 1928 strike also saw the first appearance of the “Mexican Mutual Aid Association,” a “fraternal” society launched ostensibly as a labor organization by the leech elements from among the Mexican workers. Actually it was formed for the self-enrichment of this gang who were out to fleece the Mexican workers of their meagre earnings.

In the spontaneous strikes of 1928 and January, 1930, the leadership was seized by these reformist leaders, who added to their functions the betrayal of the workers thru class collaboration tactics with the bosses and their agents. They also aided the companies by fanning the flames of race-hatred. They tried to instigate the Mexican workers against their Filipino brothers, pointing to the latter as chiefly responsible for the ills of the Mexican workers.

Entrance of the T.U.U.L.

The January, 1930, strike of the lettuce pickers saw the entrance into the Valley of the Trade Union Unity League, a new militant, workers’ union center, which has been gaining strength and influence among the masses of unskilled and semi-skilled workers of the United States.

Almost immediately the Trade Union Unity League gained an important following among the Filipino workers, who comprise the most militant section of the Valley toilers. The Mexican workers were still under the domination of the reformist officials of the Mexican Mutual Aid Association.

The T.U.U.L. proceeded at once to organize the Agricultural Workers Industrial League in the Imperial Valley. This militant union immediately made vigorous demands such as: recognition of the union; abolition of the contract system; abolition of piece work; a minimum wage of 50 cents an hour; an 8-hour work day, with double time for overtime and on Sundays; a 15-minute rest period after every two hours of work; abolition of child labor; equal pay for equal work; free ice to be furnished by grocers; better housing; better water; no race segregation. It also urged militant mass picketing; organization of workers’ defense corps, and called for unity of skilled and unskilled and workers of all races.

Reformists of the Mexican Mutual Aid Association saw in the growth of the militant union their own doom. The entire Mexican division of the strike committee consisted wholly of the Mexican Mutual Aid Association paid officials. The Filipino workers on that committee were quickly won over by the Agricultural Workers Industrial League. Reformists on numerous occasions have forcibly prevented Agricultural Workers Industrial League organizers from addressing the Mexican workers.

They constantly fought against the union, in collaboration with the Mexican Consul who with their aid, and with the assistance of the State Labor Department representative and local Chamber of Commerce, was driving the workers back to work. At the same time, in order further to demoralize the Mexican workers, their reformist leaders launched a Mexican “Marcus Garvey” scheme like the “back to Africa” movement among Negroes. A “Back to Mexico” colonization movement was started, with false promises of aid from the Mexican Government.

Meanwhile, the bosses’ attacks grew more severe. Hundreds of strikers were daily beaten and jailed by the sheriffs and police, with the aid of the fascist American Legion.

Workers Starved, Evicted

The workers and their families were starving. The bosses, whose brutality knows no bounds when profits are involved, began wholesale evictions of the workers from their wretched shacks. All food supplies were cut off by the shopkeepers. The Workers’ International Relief tried to ship truckloads of foods and tents, gathered by the Los Angeles workers for the strikers. This help was stopped by the bosses’ henchmen who forced the trucks to turn back and arrested the relief committee, all this in the face of starving men, women and children. Such were the tremendous odds against which the field workers had to pit their forces. Scab-herding agencies performed their usual task of bringing scabs to take the strikers’ jobs.

The strike was lost. Temporarily defeated, the workers returned to their fields, to labor for smaller pay under conditions made more miserable by the “victorious” bosses. This strike, however, ended the Mexican Mutual Aid Association. This fake organization collapsed when exposed by the militant Agricultural Workers Industrial League. Realizing the potential power of the Agricultural Workers Industrial League, as an uncompromising, militant organization of the workers, the bosses threw into jail a number of its organizers. While in jail, charged with vagrancy, these workers were brutally beaten by Sheriff Gillette and his henchmen. The International Labor Defense forced their release on bonds. These cases were later dismissed except that of Tetsuji Horiuchi (at present, confined in Folsom) who was turned over to the Immigration service for deportation. In his case the International Labor Defense placed a $1,000 bond and is now fighting his deportation to fascist Japan.

Shed Workers’ Strike

On the heels of the field workers’ strike, a strike of white workers in the packing sheds broke out. Groaning under the terrible speedup system, they refused to accept a drastic wage-cut.

But the strike of the shed-workers was short lived. The bosses immediately planted among the unorganized workers self-appointed leaders, who with the aid of American Federation of Labor “organizers” tried to make it a “gentleman’ s strike.” “No picketing,” “depend upon the employers,” “have nothing to do with outsiders–the Reds”–these were their slogans. The Agricultural Workers Industrial League at once issued a ringing call to the strikers, urged mass picketing and close alliance with the unskilled field workers. It called upon the strikers to fight for the abolition of the speed-up, piece-work system and for other concrete demands.

The misleaders called frequent meetings “protected from the Reds” by the police. At these gatherings the white workers were filled with patriotic speeches by the “respectable” Chamber of Commerce officials and by the “well wishing” city and county politicians–all urging the strikers, as in the lettuce workers strike, to have faith in the “fairness” of their bosses. The growers’ agents, like the Mexican reformist leaders, used gangsters as well as police to prevent the Agricultural Workers Industrial League from addressing the workers. At one large meeting, however, the strikers compelled their fake leaders to give the floor to Danny Roxas, Secretary of the League. Greeting the strikers in the name of this union, he announced the walkout of 200 Filipino and Mexican field workers in sympathy with the striking shed workers. Roxas was greeted enthusiastically by the strikers.

But while the bosses’ agents urged a “gentlemen’s strike” the scab apparatus was in full swing. Owing to the failure of the strikers to carry on mass-picketing the bosses were able to herd scabs in sufficient numbers to break the backbone of the strike. As in the case of the field workers, the shed workers returned to work under greatly worsened conditions.

Preparations for Melon Strike

Defeat failed to dampen the workers’ militant spirit and their readiness to fight against increasing speed-up, further wage cuts and unemployment. With its militant class-struggle program the A.W.I.L. was rapidly spreading its influence. At huge open-air meetings, in defiance of police terror, large numbers of Mexican and Filipino workers joined the revolutionary union. At these meetings the workers eagerly read the left-wing labor press, “Labor Unity,” “Labor Defender,” “Daily Worker” and pamphlets in English and Spanish. The new organization was also rapidly enlisting the Negro, Hindu and native white workers.

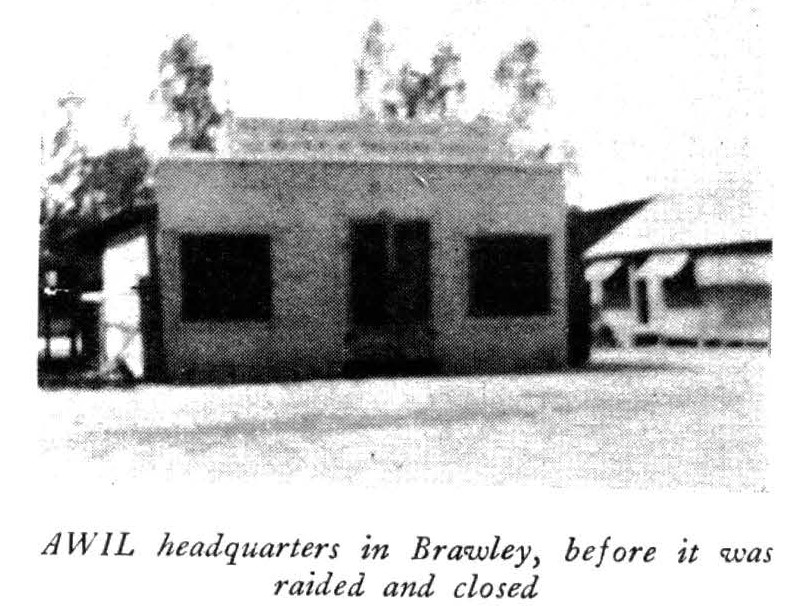

The union made its challenge to the bosses by opening its headquarters, guarded by the “Workers Defense Corps” against the attacks of the police and the American Legion fascists. Plans were made for a general strike to take place in the major season, in June and July, when cantaloupes are picked, packed and shipped.

Bosses’ Preparations

The bosses were apparently determined to crush this growing movement at all costs. The fruit and vegetable trusts fully realized the far-reaching consequences of the coming Imperial Valley struggle. They realized that the successful organization of the Valley workers meant the beginning of a powerful movement, from coast to coast, to organize the bitterly exploited agricultural workers.

Orders were issued for the general mobilization of all reactionary forces, from the Federal Government down to the fascist gangster elements. A special representative of the Department of Justice arrived on the scene. Numerous gunmen were imported from Texas and Arizona to augment the sheriff’s forces. Additional forces were deputized from among the local one-hundred-percenters. The Los Angeles Chamber of Commerce and the “Better America Federation” dispatched their highest paid, red-baiting elements to direct the onslaught upon the Valley toilers. No funds were spared in the task of crushing the workers’ militancy.

A general call was issued by the Agricultural Workers Industrial League for a broad, rank and file conference, representative of the masses of ranch and shed workers to unite the union and to adopt a definite program of strike action. In preparation for this important conference, numerous open-air and indoor mass meetings were held in Brawley, El Centro, Westmoreland, Calexico, Calipatria and other points, and also at ranches. They were attended by thousands of workers whose enthusiasm increased with the approaching struggle.

One such preliminary meeting was held in El Centro on the night of April 14 described already.

Following that night of terror the Imperial Valley assumed the appearance of an armed camp. Everywhere, along the railroad tracks, packing sheds, bridges, warehouses, in the fields and on the ranches, before the houses of government officials, were placed guards, armed to the teeth. All the pool-rooms and halls where workers gather were closed. Newspapers told fantastic stories of “plots” to blow up bridges, sheds, railroads–“plots” to burn up crops, tear down vines and what not. This hysteria filled the “respectable citizenry” with bitter prejudice and hatred against the workers. Ministers in their churches, and the one hundred per cent patriotic organizations were frothing at the mouth, denouncing the Communist Party, the T.U.U.L., the I.L.D., and passing resolutions calling upon the “guardians of law and order” to make “short work” of the imprisoned leaders of the workers. Ugly threats to take the “law” into their own hands were uttered by the frenzied patriots.

Criminal Syndicalism Law

The historic Imperial Valley struggle furnished an excuse for the revival of the infamous Criminal Syndicalism Law of California. Over 500 workers have been tried under this law since its passage, April 20, 1919, during the war hysteria days. Presumably it declares illegal any organization that “advocates and teaches the change of industrial ownership and control or effecting any political change through the commission of crime and sabotage or unlawful acts of force and violence or unlawful methods of terrorism.” Workers convicted of this charge face sentences of from one to 14 years on each count in the indictment. It is clearly aimed at workers engaged in militant struggle against the bosses. The case of the Imperial Valley defendants and other examples proves this conclusively.

The Imperial Valley struggle was seized upon by the bosses in an attempt to strike a deathblow against the hated Communist Party and other militant workers’ organizations. Thru the Criminal Syndicalism law they hoped to force underground this militant leader of the California masses. Thirty-two defendants were charged with violating this law, among whom were many leading Communists throughout the state. Bail of $40,000, an unheard of amount, was set on each of the arrested to insure their remaining in the bosses’ clutches.

The International Labor Defense began a determined drive for the release of the workers and succeeded in forcing the reduction of the bail to $5,000 on each. Fearing the rising pressure of mass protests, the bosses changed their tactics. They dismissed the charges against the 32 workers and substituted grand jury indictments against 13 workers. Bail was set at $15,000 for each. The International Labor Defense again fought for the reduction of prohibitive bail, but the same judges, of the Appellate Court, who on the previous occasion were compelled to reduce the bail, now refused to do so.

Frame-Up-the Bosses’ Favorite Method

The indictment returned by the Imperial County grand jury was drawn up on the testimony of three stool-pigeons, Sherman Barber, Charles Collum and Oscar Chormicle–all operatives of the scab-herding Bolling Detective Agency, in the employ of the growers. Notorious spies were employed to procure and manufacture the necessary evidence. Similar creatures were hired to worm their war into the new militant union and frame-up evidence.

The Trial a Mockery

Of the 13 indicted 9 actually faced trial. Two were not found. Two were dismissed on the day of the trial, June 26, in Superior Judge Thompson’s court. The trial, lasting 21 days, was conducted with a frenzy of prejudice and hatred, fanned by provocative reports of nonexistent “plots.” All attempts to organize protests under the leadership of the International Labor Defense were crushed by the police.

The workers, defended by I.L.D. attorneys, R.W. Henderson of Bakersfield, Leo Gallagher of Los Angeles and A. Blaisdell of Calexico, battled against terrific odds. The cards were stacked against them in order to railroad the workers to prison. All the shams of “legality” and “democracy” were brazenly thrown aside for the occasion; even the usual legalistic pretenses were absent.

Stool-pigeons on the stand, practically the only witness for the prosecution, repeated with clock-like precision their testimony, already given before the grand jury. This “testimony” fills a 200-page volume.

Every defendant who took the witness stand openly and proudly proclaimed his membership in the revolutionary organizations. Those belonging to the Communist Party, against which the entire brunt of the attack was directed during the trial, openly acknowledged their principles as contained in the literature, piled on the courtroom table as evidence against them. They flung into the teeth of the masters the purposes of the Communist Party, which organizes the workers for the final overthrow of the capitalist system and the establishment in its place of a workers’ and farmers’ government.

The jury was composed entirely of ranchers and business men. Even without a pretense at deliberation, it returned a verdict of “guilty” on all counts against all the defendants. This, of course, was a foregone conclusion.

This is clearly exposed in a speech made by P.A. Thaanum, commander of American Legion Post No. 25, El Centro, at the “Fifth Area Caucus” for which delegates from sixty legion posts in five southern California counties came to San Clements, California, shortly after the trial.

According to the San Diego “Sun,” Thaanum said: “The way to kill the red plague is to dynamite it out. That’s what we did in Imperial County. The judge who tried the Communists was a legionnaire, 50 per cent of the jurors were war veterans. What chance did the Communists have? That’s the way we stamped it out in our county.”

The Workers Fight On

The master-class is wrong in reckoning that its terror against the rising workers will extinguish the fires of the revolt. It has not succeeded in crushing the workers and their militant leaders, the Communist Party, the Trade Union Unity League and other revolutionary organizations in California.

Through the last strike movement the Imperial Valley workers have learned a number of valuable lessons which they will apply in the coming new struggles.

I.L.D. Mobilizes Masses for Release of Imperial Valley Prisoners

The International Labor Defense is now conducting a nation-wide campaign for the repeal of the Criminal Syndicalism Laws and for the release of the Imperial Valley militants, now serving sentences fa Folsom and San Quentin prisons. It is fighting for the acquittal of the six Atlanta, Ga., workers, and for the release of Mooney and Billings as well as for the release of all class-war prisoners.

Every class-conscious worker must join and support the International Labor Defense and actively aid in the mass mobilization of all workers. The master class must be compelled to throw open the gates of Folsom and San Quentin and other prisons and return the Imperial Valley and all other class-war fighters into the ranks of the working class.

FRANK SPECTOR, No. 48688 (Written in Prison)

Labor Defender was published monthly from 1926 until 1937 by the International Labor Defense (ILD), a Workers Party of America, and later Communist Party-led, non-partisan defense organization founded by James Cannon and William Haywood while in Moscow, 1925 to support prisoners of the class war, victims of racism and imperialism, and the struggle against fascism. It included, poetry, letters from prisoners, and was heavily illustrated with photos, images, and cartoons. Labor Defender was the central organ of the Scottsboro and Sacco and Vanzetti defense campaigns. Editors included T. J. O’ Flaherty, Max Shactman, Karl Reeve, J. Louis Engdahl, William L. Patterson, Sasha Small, and Sender Garlin.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/labordefender/pamphlets/imperial-valley.pdf