A chapter of riches from Dietzgen’s larger ‘Excursions of a Socialist into the Domain of Epistemology’ written in 1886 and included in Kerr’s 1906 collection.

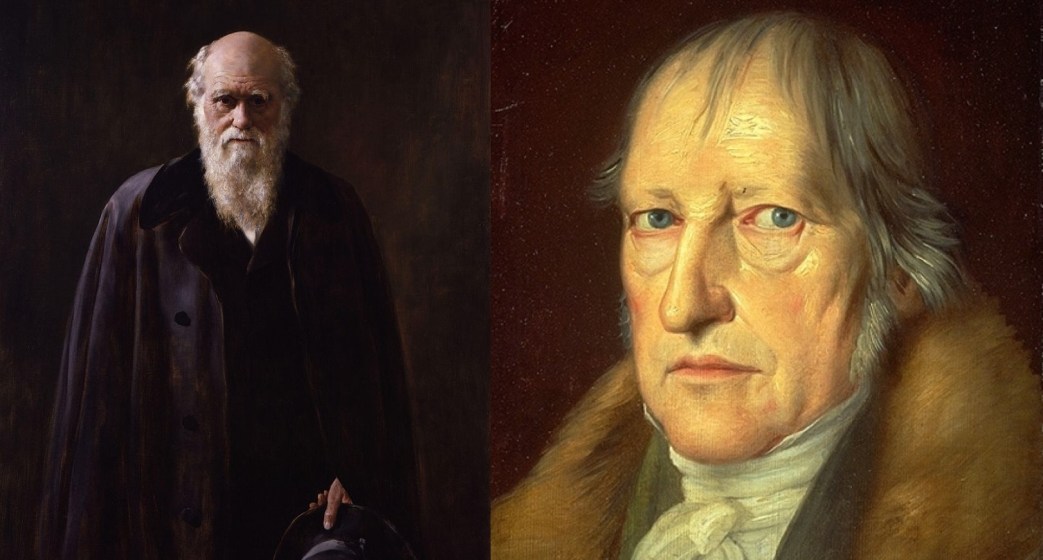

‘Darwin and Hegel’ by Joseph Dietzgen from Philosophical Essays. Translated by Max Beer and Theodore Rothstein. Charles H. Kerr Publishers, Chicago. 1906.

It is well known that philosophers have often thrown out ideas far in advance of their time which subsequently found their verification in the exact sciences. Thus, for instance, Descartes is well known to physicists, Leibnitz to mathematicians, Kant to physical geographers. It may be generally said that philosophers enjoy the reputation of having influenced by their ingenious anticipations the progress of science. We wish to point out thereby that philosophy and natural science do not at all lie inordinately far apart. It is the same human mind which works in the one as in the other science by the same method. The method of natural science is more exact, but only gradually so, not substantially. There is in every sort of knowledge, even in natural science, a certain amount of obscure, mysterious “matter,” a matter of cognition, alongside the luminous and palpable one and even the most ingenious anticipations of our philosophers are, in spite, or rather because of, their mysterious nature, still “natural.” To have worked with success at a certain conciliation between the natural and the mental is the common merit of Darwin and Hegel.

We wish to render the now almost forgotten Hegel what is to due to him as the forerunner of Darwin. Mendelssohn, in a dispute with Lessing, called Spinoza a “dead dog.” Just as dead appears now Hegel, who in his time, in the words of his biographer Haym, achieved in the world of letters a position analogous to that of Napoleon I in the political. Spinoza has long since undergone resurrection from the state of a “dead dog,” and so will Hegel, too, find his merits acknowledged by future generations. If he has lost his influence at the present time, it is merely a temporary eclipse.

Hegel, it is known, once said that of his numerous disciples only one understood him and that one, too, misunderstood him. That such a general misunderstanding is more to be ascribed to the obscurity of the master than to the lack of understanding in the disciples, admits, of course, of no question. Hegel cannot be thoroughly understood because he did not understand himself thoroughly. With all that he is an ingenious anticipator of Darwin’s theory of evolution, and with equal justice and truth one may say the reverse: Darwin is an ingenious interpreter of Hegel’s theory of knowledge. The latter is a doctrine of evolution which embraces not only the origin of species of the entire animal world, but also the origin and development of all things. It is altogether a cosmical theory of evolution. We have as little right to blame Hegel for his obscurity as Darwin for not having exhausted all knowledge with regard to the origin of species.

Truly and surely who explains everything, explains nothing. From such fantastical desire the great philosopher was quite free, though his school was ready enough to worship him. Many Hegelians really believed in their time that the master could furnish them the absolute knowledge, and that it was only necessary to open one’s mouth and swallow it. Still we also had such disciples who proceeded with earnest labors on the inherited soil and brought forth glorious fruit on the tree of knowledge.

Let us be critical towards God and all men, Hegel and Darwin included. Darwin’s theory of evolution has its indestructible merits. Who will deny it? Still a German, who has been brought up under the influence of his great philosophers, must not forget that the great Darwin was much smaller than his doctrine. How anxiously careful is he, not to draw the necessary conclusions! No one can overvalue the worth of exact research; but whoever does not perceive that it must be accompanied, if not by a flight into the Endless, at least by an endless flight, by a continuous soaring, does not understand the full value of exact experimental inquiry.

The theory of evolution which we will not say was solved, but was considerably stimulated and advanced by Hegel, received before all at the hands of Darwin an exceedingly valuable application or specification in relation to zoology. Still we must not lose sight of the fact that the specification was of no greater value than the generalization in which Hegel excels; the one cannot and must not be without the other. The naturalist combines the two, and no philosopher who deserves the name will fail do so, either; it is only the more or the less which is characteristic for the two branches of knowledge. True, the necessity of specialization would sometimes be forgotten by the best philosophers; it may not even come to their consciousness in any clear form at all. But just as often would exact science forget the general aspect of its work, while it was not the worst investigators in the scientific domain who sometimes ventured on too bold a flight to the skies. The sporadic cloud-soaring of natural science and the exact anticipations of philosophers should prove to the reader that the General and the Special harmonize together.

All art is natural art,–despite the usual opinion which places Nature and Art at an over great distance from each other; and likewise all science, philosophy included, is science of Nature. Speculative philosophy, too, has its exact object, namely, “the problem of cognition.” It would, however, be rendering the philosophers too much credit if we were to say that they have solved their problem. Other branches of knowledge, especially those of natural science, have cooperated; for science of all branches, of all nations and of all the times is the general result of a closely connected cooperation. The philosophers have assisted the naturalists, natural science has helped philosophy until the problem of knowledge is now developed, revealed and clearly worked out.

There is no question as to what ought to be the name of the subject-matter which is studied by the physician or astronomer, whilst the subject-matter of philosophy was at first much disputed so that one might say that the philosophers did not know what they wanted. Now at last, after thousands of years of incessant philosophic development, it came to be recognized that the “Problem of Cognition” or “Theory of Science” has been the object and the result of philosophic work.

In order to understand clearly the relation between Hegel and Darwin we are bound to touch upon the deep est and most obscure questions of science. The subject-matter of philosophy is just one of those. Darwin’s subject-matter is undoubted. He knew his object; yet it is to be observed that Darwin who knew his object wanted to investigate it,–consequently did not know it through and through. Darwin investigated his object, “the Origin of Species,” but he did not exhaust it. This means that the subject-matter of every science is endless. Whether one wants to measure the Infinite or merely the smallest atom, one always has to deal with the Immeasurable. Nature, both as a whole and in its parts, is inexhaustible, not knowable to its last particle, – consequently without beginning and end.

The recognition of this everyday Infinitude is the result of science, although the latter started from a transcendental religious or metaphysical Infinitude.

Darwin’s subject-matter is just as endless and unknowable to the very last particle as Hegel’s. The one inquired into the origin of species, the other into the process of human thinking. The result in both cases was the doctrine of evolution.

We have to deal here with two very great men and with a very great thing. We try to show that these men did not work in opposition to each other, but in the same direction, on the same line. They have raised the monistic conception of the world to a height and strengthened it with positive discoveries that up till then were unknown.

Darwin’s doctrine of evolution is confined to the animal species, and removes the rigid lines which the religious conception of the world sets up between the classes and species of living creatures. Darwin emancipates science from the religious class conception and ejects divine creation from science in respect to this special point. In this point he puts in the place of the transcendental creation the matter-of-fact self-development. To prove that Darwin did not fall from the clouds it is but necessary to remember Lamarck who disputes with Darwin the honor of priority. This, however does not diminish the service rendered to science by Darwin; whilst Lamarck can lay claim to the philosophical anticipation, Darwin can claim the specified proofs.

To our Hegel belongs the honor of having placed the self-development of Nature on the broadest basis, of having emancipated knowledge from the class-view in the most general way. Darwin criticises the traditional class-view zoologically, and Hegel universally.

Science makes its way out of the darkness to light. Philosophy, too, which aims at the illumination of the process of human thinking, made its way upwards; that it pursued its object rather instinctively than otherwise became by the time of Hegel tolerably patent to it.

The main works of philosophy move about the “method,” the critical use of reason, the doctrine of science or of truth, the way and manner in which man thinks, in which he should use his head. It was the aim of philosophy to inform itself of the special piece of the universe which serves as an instrument of the illumination of the universe.

We draw special attention to the dualism, to the double problem in this endeavor: the Universe was to be illuminated and at the same time the lamp, by means of which it was to be illuminated. It is preeminently this double problem which confuses the work of philosophy. Science starts from the desire of illumination and does not know at first what to take hold of, whether the Cosmos as a whole, or gradually and piecemeal. Many a time it had already entered the practical road without having arrived at any guiding principle. In the time of Hegel the problem was as yet to a large extent obscure, still the way had been considerably cleared. It was Kant who desisted from the direct search after the whole wisdom of the world and took up, at first, specially the piece of the Universe called thinking. This piece, according to tradition, belonged preeminently to the metaphysical class of the transcendental things. Kant by his critique has done enough to emancipate the intellect from this sinister class-character. Had he succeeded in this completely, had he proved to us entirely that Reason is a thing which together with other things belongs to the same natural series, he would have, like Darwin, delivered a crushing blow against the transcendental way of classification as well as against Religion. No doubt, Kant has done so, but he did not cleanly cut off the ear of Malchus and left therefore still some work to his successors.

Hegel was an excellent successor to Kant. When we place those two side by side, the one illustrates the other, and the two illustrate Darwin. Kant chose Reason as his special object of study. In dealing with it he could not help drawing other things within his circle of re search. He studies Reason as it behaves in the active pursuit of other sciences; he studies it in its relation to the rest of the world and tells us a hundred times that it is limited to experience, to one indivisible world which is temporal and at the same time eternal. Hence it ought to be clear to the reader that in the teaching of Kant general knowledge of the world and special critique of Reason are united.

It is clear at a glance that Kant’s discovery of the limitation of human Reason by experience was both philosophic science and scientific philosophy. The same holds good of Darwin’s doctrine of the “Origin of Species.” He proves on that point scientifically that the world develops in itself and not from the heavens above–“transcendentally” as the philosophers say. Darwin is a philosopher, though he makes no claim to that. To have worked for the monistic conception, both by his special demonstrations and general conclusion, he has in common with Kant and Hegel.

Hegel teaches the theory of evolution; he teaches that the world was not made, is not a creation, has not an invariable and fixed existence, but is always in the making by its inherent force. Just as with Darwin the classes of animals are not divided by unbridgeable gulfs from each other, but on the contrary, are linked with each other, so with Hegel all categories and forms of the world, nothing and something, being and becoming, quantity and quality, consciousness and unconsciousness, progress and inertia–all inavoidably flow into each other. He teaches that there are differences everywhere, but nowhere–“exaggerated,” metaphysical, transcendental differences. According to Hegel there are no such things which differ from each other “essentially.” The difference between essential and non-essential is only to be understood as relative and gradual. There is only one absolute thing, and that is Cosmos, and everything which hangs about it are fluid, transient, changeable forms, accidentals or properties of the general being which in Hegel’s terminology bears the name of the Absolute.

Nobody will think of assorting that the philosopher has accomplished his work in the most lucid and complete manner. His teaching made further development as little superfluous as that of Darwin, but it gave an impetus to the entire science and the entire human life,–an impetus of the highest importance. Hegel has anticipated Darwin, but Darwin unfortunately did not know Hegel. This “unfortunately” is not a reproach to the great naturalist, but merely a suggestion to us that we should supplement the work of the specialist Darwin by the work of the great generalizer Hegel and proceed still further to greater clearness.

We have stated that Hegel’s philosophy was so obscure that the master could say of his best disciple that he misunderstood him. It was with the view to illuminating this obscurity that not only the succeeding philosopher Feuerbach and other Hegelians have worked, but also the entire scientific, political and economic development of the world. When we consider Darwin’s discoveries, and the latest theory of the transformation of energy, it must at last become clear to us–what occupied the best minds during three thousand years of civilized life–that the world is not made up of fixed classes, but is a fluid unity, the Absolute incarnate, which develops eternally and is only classified by the human mind for purposes of forming intelligent conceptions.

Ernst Haeckel, the well-known naturalist and disciple of Darwin, says in his preface to a paper read by him at Eisenach on September 18, 1882, and published afterwards at Jena,

“that the present attitude of Virchow towards Darwinism is entirely different from that which he assumed at Munich five years previously. In rising at the above mentioned Congress of Anthropologists immediately after Dr. Lucæ he (Virchow) not only turned against this latter’s assertions and paid Darwin the merited amount of his high admiration, but he expressly acknowledged that his more important propositions are logical postulates, irresistible demands of our reason. ‘Yes,’ said Virchow, ‘I do not for a moment deny that the generatio æquivoca is a sort of general demand of the human mind…Also the idea that man has evolved through a slow and gradual development from the ranks of lower animals, is a logical postulate.’”

The enlightened knowledge of Nature, proceeds then Haeckel in his speech,

“recognizes only that natural revelation which is open to everyone in the book of Nature and can be learned by every one who is free from preconceived notions and is endowed with healthy sense; and a healthy mind. From the study of that book we gain that monistic and purest form of belief which amounts to a conviction in the unity of God and Nature and which found long since its complete expression in the pantheistic professions of our greatest poets and thinkers.”

That our greatest poets and thinkers exhibit the tendency to a monistic and pure form of belief and strive after a physical view of Nature which makes all metaphysics impossible and excludes from the scientific world the supernatural God together with the miracle-rubbish,–that is quite true. But when Haeckel gets carried away by his feelings so as to declare that the tendency “has long since found its most complete expression,” then he is laboring under a very grave delusion,–a delusion as regards even himself and his own profession of faith. Haeckel, too, does not know yet how to think monistically.

We shall presently justify our reproach; but it may be stated at once that it affects not only Haeckel, but the entire school of our modern natural science, because it has neglected the results of two and a half thousand years of philosophic research, which has back of it a long empirical history not less so than experimental science itself.

The above mentioned lecture by Haeckel contains the following passage:

“We should like to emphasize especially the conciliating and soothing effect of our genetic view of Nature,–this the more so as our opponents are continually engaged in trying to ascribe to it destructive and dissolving tendencies. The latter are supposed to work not only against science, but against religion also and in so far against the most important foundation of our civilized life in general. Such serious charges, in so far as they really are based on conviction and not merely on sophistical syllogisms can only be explained by a lamentable lack of knowledge of what constitutes the real essence of true religion. This essence is not based on a special form of faith, of domination, but rather on the critically sound conviction of the ultimate unknowable and common cause of all things. In this acknowledgment that the ultimate cause of all phenomena is with the present organization of our brain unknowable, critical natural philosophy meets with dogmatic religion.”

There are three points in this confession of Haeckel which should be kept separately and prove to us that the “monistic view of the world” has even in its most radical and scientific representative not found as yet its complete expression.

- Haeckel wants to clear natural science from the reproach of having “ destructive tendencies.” This enlightened science, which knows only of a natural revelation and has its religion or form of faith in the unity of God and Nature should-

- Not act destructively upon the prevailing religion which is based on a supernatural or unnatural revelation. This unnatural religion, forsooth, possesses a true essence which is also recognized by the natural or scientific religion. This is the common cause of all things.

Very well, the old belief has the common cause of all that is in a personal God who is supernaturally, indescribably, inconceivably a spirit or a mystery. The new religion à la Haeckel believes to possess in Nature–also named God–a common cause of all things, and so the two forms of faith possess a common cause. The difference only is that the cause, recognised by natural science, is the every-day Nature which, of course, is mysterious enough, yet its mysteries, its riddles are only such as natural science is engaged in solving. The sort of Nature which Haeckel transforms into a God, which he deifies, is also a mystery, but only a natural, an everyday mystery, whilst the supernaturally revealed God is, according to all that is said of him, of a nature thoroughly inexpressible, undefinable by any words at our command. Or, since one cannot help treating the good religious God with human words, it is easy to understand how in such process all these names and words lose their human sense. Just put the religious God and the natural God of Haeckel side by side: both of them are omnipotent; Nature makes everything which is made, but only in a natural, every-day sense. The good God in Heavens, too, makes everything, but not naturally; he makes it unnaturally in a sense and in a way which does not even admit of being defined, of being expressed. The good God, forsooth, is a spirit, but not such as dwells in old castles, nor such a limited one as man has in his head, but a spirit like no spirit, a monster-spirit, a monster-mind whose constitution cannot even be expressed in words.

Before we pass to the third point of the “purest form of faith,” we must consider a little closer the two already mentioned. It will then be the more easy to dispose of the third and last one as well as of the final combination of all the three in one.

The difference between the everyday natural and the unnatural, between the physical and metaphysical revelation, religion or divinity, is so great that the enlightened view of Nature, as represented by Haeckel the Darwinian, would have been justified to forego the old names and the revealed divine religion and put “destructively” against it the monistic view of the world. By not doing that, Darwinism only manifests the limitation of its theory of evolution. In so far as it wants to remain monistic it ought to have viewed Nature only physically, not metaphysically. It must see in Nature the primary cause of all things, but not a mysterious one, that is, a not yet explored, but never an inexplorable cause,–inexplorable in the metaphysical sense.

That Haeckel, however, the most radical representative of natural science monism, still rides that dualistic horse, is proclaimed openly by the third point which finds the ultimate cause of all phenomena “with the present organization of our brain” unknowable.

What is knowable?

The whole context to which that word belongs shows conclusively that our monistic scientist is still in the mire of metaphysics. Nothing in the world, not an atom of it, is to be known out and out. Everything in the world is inexhaustible in its secrets, no less than it is imperishable and indestructible in its essence. With all that, we learn every day more and more to know the things, and learn that there is nothing which is closed to our mind. Just as the human mind is unlimited in the discovery of mysteries and problems, so, on the other hand, the inexhaustible and the unknowable yield themselves readily and unreservedly to its inquiries and its attempts to solve them.

It is due to the “old belief” that the words, the speech, have acquired a double meaning,–a natural, relative and common-sense one, and a transcendental, metaphysical one. The reader may notice the double effect of natural science when it is compromised by metaphysics; it contains mysteries and propagates, by their solution, the conviction that what was formerly a mystery becomes through research an ordinary, everyday thing in the chain of interrelation. Nature is full of mysteries which reveal themselves to the inquiring mind as ordinary properties. Nature is inexhaustible in scientific problems. We sound them and we can never come to an end with this sounding. The human common-sense is quite right when it finds the world or Nature unfathomable, but it is also right when it repudiates all metaphysical unfathomableness of the world as transcendental folly and superstition. We shall never finish with our exploration of Nature, and yet the more natural science proceeds in its exploration the more strikingly patent it becomes that it need not at all fear the inexhaustible mysteries, that “there is nothing which resists it” (Hegel). Hence it follows that the inexhaustible “primary cause of all things” is being pumped daily with our instrument of knowledge which is no less universal or infinite in its capacity for exploration than Nature in setting problems.

“With the present organisation of our brain!” No doubt. Our brain will yet, through sexual selection and struggle for existence, develop enormously and probe more and more the natural cause of things. If that phrase is meant in this sense, then we perfectly agree. But it is not meant so by the metaphysically prejudiced Darwinian. The human mind is supposed to be too small for the thorough exploration of the world, in order that we may believe in a monster-mind and not combat him “destructively.”

Darwin with all his merits was an exceedingly modest man; he was content with a special branch of inquiry. Everybody should be as modest, but not everybody should limit himself to the same specialty. Science has not only to investigate the morphology of plants and animals; it has to deal also with the problem, as to how the unknowable changes into the knowable, and must not exclude from hi province the ultimate cause of all existence.

Hegel has propounded the doctrine of evolution on a far more universal scale than Darwin. We do not wish on that account to prefer or to subordinate the one to the other, but merely to supplement the one by the other. If Darwin teaches us that amphibia and birds are not eternally separated classes, but emerge from one another and merge into one another, then Hegel teaches us that all classes, that the whole world, is a living being which has nowhere rigid limits so that even the knowable and unknowable, the physical and metaphysical, flow into one another, and the absolutely Inconceivable is a thing which belongs not to the monistic, but to the dualistic, religious view of the world.

“We have to go back twenty-five centuries, to the dawn of classical antiquity in order to find the first germs of a natural philosophy, that pursued with a clear purpose Darwin’s object, viz., to find the natural causes of the phenomena of Nature and thus to dissipate the belief in supernatural causes, in miracles. It was the founders of Greek philosophy in the seventh and sixth centuries B.C. who laid this true cornerstone of knowledge and tried to discover a natural common cause of all things” (Haeckel, l.c.).

Now, if our esteemed naturalist drops this “natural” cause and substitutes a mysterious cause which is so wonderful that we cannot possibly know anything of it, he again leaves us a metaphysical ultimate cause to believe in, which brings us in line with religion.–Does he not thereby play false to the common aim of Darwin and his critical natural philosophy?

According to our monism Nature is the ultimate cause of all things; it is also the cause of our faculty of cognition; yet this faculty, according to Haeckel, is too small to know the ultimate cause! How does that fit in? Nature is recognised as the ultimate cause, and yet it is to remain unknowable!

The fear of destructive tendencies has taken hold of even such a determined evolutionist as Haeckel. He abandons his own theory and lands in the belief that the human mind must content itself with the phenomenon of Nature and is unable to reach the true essence of it. The ultimate cause is, according to our naturalist, an object which does not come within the province of natural science.

“The contentedness in receiving and the parsimony in giving are not virtues in the domain of science,” says Hegel in the preface to his Phenomenology of the Mind. He goes on saying: Those who merely seek edification, who desire to envelop in a mist the earthly manifold richness of existence and of thought, and hanker after the vague enjoyment of this indefinite divinity, may look out where to find it; they will easily discover the means to rave about it and to put on mysterious airs. But philosophy must take care not to wish to become edifying.

Darwin’s aim has been represented by his most acknowledged disciple as a philosophic one,–to find out the natural causes and to dispel the belief in supernatural intervention and miracles. And yet the wonderful inconceivableness of the common cause of all things, the wonderful limitation of the human mind must still remain untouched for the sake of edifying conciliation!

Our reproach against Haeckel, the Darwinian, amounts to this: he has not assimilated the results of two and a half thousand years of philosophic evolution and there fore, though he may, perhaps, know very well the nature of “the present organisation of our brain,” he nevertheless sadly tacks the knowledge of the process of cognition which is a thing different from the physiology of the brain. At least, so much do the above quoted passages show that Haeckel’s ideas of the natural and unnatural, of the wonderful and knowable, as well as his ideas of the natural divinity and the divine nature are not monistic, but are still permeated by a very reactionary dualism.

As to the pantheistic professions of our greatest poets and thinkers,–professions which culminate in the conviction of the unity of God and Nature, Hegel has left us a very characteristic doctrine. According to it, we not only know the unity of things, but also their difference. A poodle and a bloodhound are both dogs, but this unity does not prevent differences. Nature has much likeness to God,–it rules from eternity to eternity. As our mind is its instrument, a natural instrument, Nature knows everything that there is to be known. It is omniscient. Yet natural wisdom is sufficiently different from divine wisdom that there are enough scientific reasons for the destructive tendencies to do away entirely with God, religion and metaphysics,–to do away in a rational manner so far as they can be done away with. The confused ideas have been before and will therefore remain as have-beens in all eternity.

The Hegelian, too, assumes towards religion an attitude which is merely scientific, not irreconcilable. We readily recognize religion as a natural phenomenon which in its time and under special circumstances was fully justified, and, like all phenomena, like wood and stone, carries within its transient shell an eternal germ of truth. What Hegel has failed to do, or done imperfectly, was supplemented by his follower Feuerbach. He brought that germ to light and showed that burned wood does not come to nothing, but turns into ashes and undergoes in that process such a change that the use of the former name is no longer permissible. The transformation of wood into ashes is a development; likewise religion develops into science. And when the Darwinian, in spite of that manifests a desire to leave in the ultimate cause of all things something undeveloped and undevelopable, something mysterious and metaphysical he only shows that he has not grasped the doctrine of evolution in its universality and that the great Hegel who developed the doctrine of cognition is for him a “dead dog.”

Let us cast a cursory glance over Darwin’s work. His subject matter is the animal in general, the animality, the animal life in its generic sense. Before Darwin we only knew living individuals, and the general animal was a mere abstraction. Since then, however, we have learned that not only individuals, but also the general animal, is a living being. The animality exists, moves and changes, undergoes a historic development, is a widely ramified organism. Before Darwin the ramifications or divisions of the animal world were marked off by zoologists according to a fixed system. They divided it into classes, fishes, amphibia, insects, birds, and so forth. Darwin has introduced life into this system. He showed us that animality is not a dead abstract entity, but is a moving process of which our knowledge has up till now given us but a scanty picture. And if the old knowledge of the animal world was a scanty picture and the new one is more substantial, more complete and truthful, then the gain from it by our knowledge is not confined to the animal world. We also gain at the same time an insight into our faculty of cognition, viz., that the latter is not a supernatural source of truth, but a mirror-like instrument which reflects the things of the world, or Nature.

Darwin was the negation of a metaphysician. Without, perhaps, knowing it or wishing it, he took metaphysics, the belief in the miraculous, by the throat; he removed in zoology the unnatural class-lines and gave the edifying belief in the metaphysical, wonderful nature of the human organ of cognition a blow which stuck, and substantially illuminated philosophy, the critique of reason or theory of cognition.

If not Darwin himself, at least, his follower Haeckel told us that his master was a glorious fighter against metaphysics. This is the ground on which he meets Hegel and all philosophers as allies. All of them strove after illumination,–especially the illumination of the metaphysical dimness, though they themselves were laboring more or less under it.

Hegel has much in common with the old Heraclitus, nicknamed “the Obscure.” Both of them taught, that the things of the world do not stand still, but flow, that is, develop, and both of them deserve being nicknamed “the Obscure.” To illuminate a little Hegel’s obscurity it is necessary to pass in brief review the development of philosophy.

Science began its career more as philosophy than natural science, that is, it lived at the beginning more in metaphysical speculation than in real Nature. True, mankind had already made some excursions into natural science before, just as our most modern naturalists sometimes land in a backward philosophy; still we must say in all truth that the old cultivators of science were philosophers while the modern were naturalists. Now at last the conciliation is near at hand, or even already concluded. Now the question is of a completely systematic, natural view of the world which has neither before nor behind it anything supernatural, “edifying” or metaphysical. Since the days of the Greek colonies, since Thales, Democritus and Heraclitus, Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato, philosophy sought to solve the riddle of Nature. But they were continually in doubt and in the darkness as to the ways and means of inquiry, whether the solution of the problem was to be sought in the outer or inner world, in matter or in mind. And in modern times, too, when after a thousand years of darkness a new scientific day dawned, and the philosophers took up again the work of the old predecessors,–at the time of Bacon, Descartes and Leibnitz–the dispute about the “method” and the proper “organon” for the acquirement of truth was still going on. The whole thing appeared doubtful,–especially the nature of truth which was to be investigated and the riddle which was to be solved, whether it be natural or supernatural,–indeed, so doubtful that, as is well known, Descartes made Doubt the primary condition and the cardinal virtue of inquiry.

Yet science could not stop at that point. It had to arrive at Certainty,–particularly on that question which for Descartes and for all other philosophers was the most pressing. It needed certainty about the method, that is, how one must proceed in the inquiry in order to arrive at scientific truth which is identical with certainty. At the same time natural science already began to apply practically the method which the philosophers were still searching for. And the great Descartes was, too, partly a scientist, and proceeded in philosophy so far as to make the above mentioned method the definite, clearly-conceived subject of his main work.

And now the light spreads more and more. The metaphysical, the inconceivable, the mysterious has to go, and must be driven out of science, and its place taken up by certainty, by the undoubted. The process is in full swing. The philosophers develop mightily and the scientists render them mighty assistance.

And here comes the great Kant with his question: “How is metaphysics possible as a science?”

Let us keep in mind what the old Königsberg philosopher means by “metaphysics.” He means by it the miraculous, the mysterious, the inconceivable, that is the traditional, theological subject-matters: “God, Freedom, Immortality.”

You have been talking about it a pretty long time, says Kant. I will now try and see whether it is really possible to know anything about the matter. And he takes as his model Copernicus. After astronomy had for a long time allowed the sun to move round the earth and not much came out of it, Copernicus turned the method upside down and attempted to see whether it would not be better when the sun was fixed and the earth moved round. With the assistance of the faculty of cognition Man has, up to the time of Kant, tried to probe the great metaphysical, the existence of the world-miracle. The famous author of the Critique of Pure Reason turns the thing round and takes the piece of Nature which man feels glowing in his head,–the lamp of illumination of which some empirical information had been gained before–and attempts to find out, whether with this lamp it is possible to illuminate the great sea-serpent which since the Christian era has been known under the name of God, Freedom and Immortality, but in classical antiquity was designated by its wise men as the True, the Good and the Beautiful.

This classical name is very apt to mislead us. True, good and beautiful specialties, as they are daily cultivated by the exact sciences, must clearly be distinguished from the great sea-serpent which floated before the eyes of the ancients when they investigated the abstract ideas. The Christian name with which Kant designates the metaphysical monster is in the present stage of the problem better calculated to bring out the difference between physics and metaphysics, between the perceptible Nature and the senseless Beyond.

On the other hand, we are also apt to miss the true importance of the sea-serpent, if we concentrate our attention exclusively on its religious color. Its belly is yellow and glitters with God, Freedom and Immortality; but its back takes the color of its environment and by this mimicry it is able, like the white hare in the snow, to escape our eye. When, however, we come nearer and inspect the thing closely, we find on its grey back the words “The True, the Good, the Beautiful” imprinted in Greek letters of a dark hue. If we resume in one word the inscriptions which the philosophical-theological-metaphysical sea-serpent bears on its back, the beast will, perhaps, be most aptly characterized by the beautiful name, “Truth.” The double meaning of this word ought not to be missed. The sea-serpent-truth is transcendental. Still ft rests on a natural basis, on the basis of natural truth, which, of course, must be distinguished from the transcendental one. The natural truth is the scientific truth; it is not to be gazed at either with enthusiasm or with “edification,” but it must be contemplated soberly, and it is so general that all things, even the paving stones, belong to it. The sea-serpent-truth is a human delusion of the childish prehistoric times; the sober truth is a collective name which embraces in one conception both true fancies and true paving stones.

Kant asked: How is metaphysics, that is, the belief in the supernatural, possible as a science? And he replied: This belief is not scientific. After having examined the intellect in its various faculties Kant comes to the conclusion that the human mind can only form images of the phenomena of Nature and as far as science goes, does not know and does not wish to know of any other “true” spirit. Though the time for such a radical pronouncement was not ripe yet, nevertheless it is well known that Kant concludes his inquiry with the statement that Reason–meaning thereby the highest measure of our intellectual efforts–can only understand the mere appearances of things.

The inquiry into the nature of the sea-serpent has in the hands of the philosopher Kant changed into the scientific and sober question, what sort of a light is it and what is it to illuminate. Still Kant, too, was unable to extricate himself from the muddle, whether he should combat the metaphysical monster, or criticize Reason, or do the two things at the same time. His successors, Fichte, Schelling and Hegel, had to take up the same work and continue it. By the inquiry into the human mind the head of the sea-serpent is to be crushed,–that is certain, so much had the road been cleared by the Königsberg Copernicus. Still we must not allow ourselves to be carried away by the enthusiasm for his heroic deed to such an extent as to ignore the fact that neither he nor his followers have completely purged their emotions from the wretched metaphysics, from the belief in a higher truth than the natural one. They rather guess at the monstrous than perceive it, and they only gain their victory step by step.

Kant argues as follows: Even if our Reason be limited to the knowledge of natural appearances, even if we could not know anything beyond that, we still must believe in something mysterious, higher, metaphysical. There must be something behind the appearances, “since where there are appearances there must be something which appears.” So concludes Kant,–only seemingly a correct conclusion. Is it not enough that natural appearances appear? Why should there be anything else behind them, – something transcendental, inconceivable–but their own nature? However, let that pass. Kant expelled–at least formally–metaphysics from scientific pursuits and relegated it to the province of belief.

That was in the eyes of the successors and especially of Hegel too little. The belief which Kant had left, of the limited mind, the limits which he had set to scientific inquiry, were to this giant of thought too narrow; he soared into the Universe and there “ there should be nothing to resist him.” He wants to escape from the metaphysical prison into the fresh physical air; and this is not to be understood in the sense as if Hegel himself were mentally free and wanted to assist others to gain such freedom. No, the philosopher himself is prejudiced and wants to be instructed. His mind, his flame is but a portion of the universal light which glows in every man, which wants to, and can illuminate everything, but can only proceed step by step.

In consequence of the more or less entangled nature of things our discussion, too, cannot be free from entanglement. We wish to elucidate the connection between the old philosophers and their “last knight,” then between Hegel, Darwin and the whole science. Hence our episodical excursions in various directions.

In order to elucidate the teaching of Hegel in relation to that of Darwin it is necessary above all to keep in mind the bewildering double nature of all science. Every scientist–and Darwin, too–illuminates not only his special subject-matter on which he is consciously engaged; but his special contributions at the same time inevitably assist in illuminating the relation of human mind to the world as a whole. This relation originally was a slavish, religious, non-human one. The human mind considered itself and the world as a riddle which it was unable to illuminate with the light of his knowledge, but which could only form fantastical imaginings of the overpowering metaphysical thing. Every contribution which has been made to science since the beginning of human history has weakened the slave chain in which our race was born. Both the philosophers and the scientists were fettered by it, and the emancipating work was done conjointly and has proceeded vigorously to this very day. The scientists, however, have no reason to look down upon their colleagues, the philosophers. They, the scientists, with Darwin at their head, look straight in the face of their selected special subject-matter, and squint at the same time at the general riddle, the riddle of the Universe. Even when Darwin declares explicitly that science has nothing to do with the sea-serpent and thus clears it out of his way or relegates it à la Kant to the province of belief, these are merely subjective limitations or anxieties which may be pardonable as far as the individual is concerned, but must not fetter the universal research of the human race. Now, there cannot be knowledge here and belief there; it is the solution of all doubt that is required, and whosoever’s doctrine is opposed to such a demand will be rejected by posterity as a piece of cowardice.

It was said before that the scientists boldly contemplate their specialties while they squint at the monstrous miracle-world. We may now add that the philosophers let the rays of their intellectual light fall direct upon the great sea-serpent and get thereby so dizzy that they squint back at their own light as something metaphysical. The confusion which arises from the bewildering double nature of knowledge is now overcome by the discovery that the human mind, or the light which illuminates the things, is of the same nature, of the same kind as the objects which are illuminated and that is the result of ages of philosophic thinking.

Kant left to posterity the excessively humble opinion that the light of cognition of his race is far too small to illuminate the great, wonderful beast. By showing that it is not too small, that our light is neither smaller nor larger, neither more wonderful nor less, than the object which has to be illuminated, the belief in miracles, in the sea-serpent, i.e., metaphysics, is at once done away with. Simultaneously man loses his excessive humbleness; and it was our Hegel who substantially contributed to that result.

A thorough perception of the situation requires the historical reconstruction of philosophic development, piece by piece in all the details. Still, we may in this respect, too, content ourselves with a brief sketch, since general education is now so widely spread, that the interested reader can easily supply himself the fitting illustrations to the picture presented here.

The labors of Darwin and Hegel, however differing in other respects, have this much in common that both of them combat the metaphysical, the non-perceptible and the nonsensical. While proposing to explain both the difference and community of the two thinkers we can not help drawing within the province of our investigation the great sea-serpent. The sport, however, is rendered difficult by the numerous names which in the course of History have become attached to the monster. What is metaphysics? According to the name it is a branch of study,–or rather, it was, and now it casts its shadow on the present. What is it after? What does it want? Of course, enlightenment! But on what subject? On the subject of God, Freedom and Immortality. This sounds nowadays quite parson-like. And even if we should characterize its subject-matter by the classical names of the True, the Good and the Beautiful, there is still enough occasion left to make it clear, both to ourselves and to the reader, what it is for which the metaphysicians are looking? Without this it is impossible to measure and to explain what Darwin or Hegel accomplished or left undone and what, in consequence, there is still left for posterity to accomplish.

The sea-serpent cannot be at all characterized by an apt name since it has so many. Its origin goes back to the childhood of the human race, and the comparative philology is agreed upon the point that in those prehistoric times the things had many names and the names denoted many things, and this resulted in a great confusion which in modern times has been investigated and recognised as the source of mythology.

One has only to see what, for instance, Max Müller has to say on that point in his Chips from a German Workshop. We are told there that the heathen and Christian fables about God, etc., were no empty nonsense, but natural developments of the store of speech. It was the poetical predilections of the ancient peoples that found vent in the language. Sober as we have become by now we still use such expressions as that of “killing time.” Such pictures, full of sense and intelligence, served the ancients, inclined as they were to poetry and transcendentalism, for the filling out of the metaphysical wonder-world. Names are and have always been images of things. Those who forget this simple fact and ascribe to words a transcendental sense, are engaged in metaphysics. The latter is the general idea underlying all fables. The poet is a conscious fable-spinner, fables are unconscious poetry. Hence it follows that when we speak of the wonder-world it all depends on the consciousness with which we accompany our words. Everything which exists is heavenly, divine, in describable, inconceivable if we only mean to give there by vent to our overpowering emotions caused by the natural wonderfulness of Nature. But nobody may in a sober manner express himself to the effect that every thing which exists is a sea-serpent and is bound up with the unnatural truth or with something which the metaphysical enthusiast calls God, Freedom and Immortality.

It was not to overcome poetry, but to overcome the unconscious, exaggerated poetry that constituted the object of the movement for human enlightenment in which all workers of science have participated, partly deliberately, partly against their will.

The Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement. It remains a left wing publisher today.

PDF of original book: https://archive.org/download/someofphilosophi00dietiala/someofphilosophi00dietiala.pdf