Liebknecht sees the outlines of the coming Civil War in France as he analyses the ‘peace,’ Bismark’s militarism, and the Social Democrats attitude towards German elections and parliaments.

‘Letter from Leipzig, XI’ by Wilhelm Liebknecht from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 7 No. 35. April 22, 1871.

LEIPZIG, March 5, 1871.

To the Editor of the WORKINGMAN’S ADVOCATE.

The position in which our party stands to the elections for the Reichstag will become clear from the following resolution, which was carried unanimously in our last Congress, at Stuttgart, in June last:

“Resolved, The Social-Democratic Party takes part in the elections for the Reichstag and the Customs Parliament solely from agitatory propagandistic reasons. Our representatives in the Reichstag and Customs Parliament1 have endeavored, as for as it is possible, to promote the interests of the working classes, but on the whole they have to stand on the negative, and shall use every opportunity for unmasking and exposing the parliamentary doings of both these bodies as a hollow comedy.”

Since then the North German Reichstag has been changed into a German Reichstag, and the Customs Parliament–that most unfortunate and hopeless of Count Bismarck’s creations–has been thrown into the lumber room; but those are mere outward changes, which no ways affect the essence of things, and so the Stuttgart resolution is still in full force. You see from it we do not expect anything from a parliamentary body which is altogether deprived of power, and so composed that the majority will oppose every serious struggle for power. All our chances are lying out of doors, and consequently our energy must be concentrated upon organizing pressure from without. Whether we have many or few, any or no representatives in this Reichstag, does not matter. Had we the majority, a nod of Count Bismarck would send them to prison. What matters to us is to make the best use of the facilities which the election movement offers for the propagation of our principles. The Prussian Empire, like the French, will not be overthrown by Parliamentarism, its own lacquey and court-fool.

That we are not alone in our estimation of the Reichstag, and that the great bulk of the people has, in spite of official puffing, no higher opinion of it, may be gathered from the fact that in many electoral districts no candidates have yet appeared. And in five days the elections are to take place!

Though the official, officious and otherwise “national “–that is, Bismarckian–press continues to brag in a manner which shows that the German modesty of these representatives of our nation is ten times as impudent as the most impudent rhodomontading of French swashbucklers, military and civil, has ever been. Yet in the very same papers articles are appearing since about a fortnight which sufficiently betray the embarrassing situation of the Prussian government. Peace there will be; no doubt any more. A “glorious” and “profitable” peace, too. Most likely a handsome piece of land annexed, and certainly a lot of money pocketed. The land annexed will not fill one single hungry German stomach, it is true, and the money pocketed will not dry the tears of one single child or wife orphaned or widowed by the war. But never mind–glorious the peace will be for those that made the war, and profitable, also, to some extent. The profit is not so sure as the glory. And the misgivings about this point are so harassing that they ooze out through the pores of the else-so-discreet press bureau. Peace we have, or shall have in a few days, but what next? What next? Yes–that is the ominous question which rose before Mr. Bismarck when he made his remark about “our difficulties beginning after France is conquered.” What next? Frenchmen are human beings, with human feelings and human passions. And in human nature it is, that a man whom you beat and humble becomes your enemy, unless, by making atonement, you succeed in gaining his friendship. Applied to the case in hand, this means that Germany, or Prussia, has now to choose between two courses–either to treat France kindly and generously, with a view of eradicating the hatred engendered by five months of horrible, monstrous ill-usage; or to crown this ill usage by a peace which lowers France and renders her the mortal enemy of Prussia. A third course does not exist. Either the one or the other. Either we must resign all ideas of territorial aggrandizement, or we must take the consequences.

The former would be hard–indeed, morally impossible to us. And the latter–well, what are the consequences we should have to take? “We” have killed and disabled some two or three hundred thousand French soldiers, but we have lost quite as many ourselves, and there are still some two or three millions of Frenchmen between the ages of twenty and forty left, who, in a short time, may become excellent soldiers. And then? Ah, if we believed in what we are talking of our military superiority! But, unfortunately, self-praise not only has a bad smell, as the impolite German proverb says: but it has also the great fault of convincing neither its manufacturer nor its intended purchaser. We know very well that we have been telling a fib when we told the people that one German soldier was a match for two, three, four, half a dozen French soldiers. We know very well, that our much-vaunted military superiority has been due to a lucky combination of favorable accidents and chances, wholly independent from our intrinsic value and valor. We know very well that the Frenchmen were not prepared for the war in the least, and that up to Sedan we had, in every tight, far outnumbered them, besides the incalculable advantages which readiness gives over surprised confusion. We know very well that the French Emperor helped us to conquer his unready army, first by imbecility, and then on purpose. We know very well that after Sedan the French had no regular army left, and that the troops opposing us were raw recruits, with inexperienced officers, to beat whom could be no merit for disciplined soldiers. We know very well that these raw recruits were fast getting formed into disciplined soldiers, able to beat any army not outnumbering them. We know very well that if Jules Favre had not made his coup and by it divided the French Republic, setting one half against the other, it would have been out of our power to continue the war much longer. We know very well that our talk about the inexhaustible resources of Germany is miserable humbug, and that these resources are, in fact, well nigh exhausted for aggressive warfare.

This, and much more, we know very well, and because we know it, that “What next?” is such a perplexing question. We shall take Frenchland–to withdraw our figures from what they have clutched, would be unnatural in us–we shall make the Frenchmen our enemies. For a year, for two years, perhaps for ten years they will have plenty of work at home, healing the wounds, repairing the losses–we have done our best to give them occupation in that line. Heaven, our good ally, will bear us witness!–and when the wounds are healed and conquered France feels her old strength again? Will she not set her whole heart on a “policy of revenge?” Will she not look for confederates? And are there not many governments in a mode to assist her? England, Austria, even Russia–not to mention the small fry: Denmark, Holland, Belgium, Switzerland, Sweden, who would see us going to the dogs rather today than tomorrow–are not over-fond of us. On the contrary; were the two former not at present paralyzed by a parcel of timid, nay, cowardly statesmen, we should have been stopped long ago–and as for the rulers of Russia they liked us amazingly, while we danced to their music and while our King was the obedient viceroy or Lord Lieutenant of the Czar, but they will do their utmost at St. Petersburg to prevent the Prussian tree from growing into the sky; and if the Frenchmen were to offer them full liberty of action on the Danube for instance, on condition of help against us, by Jove the prospects are no rosy ones; and what remains for us poor press bureau scribes, but to solace the Republic, that lamb-like animal, which will be deceived, (is not happy without–vult decipi) by pointing at our glorious army, doubling the number of our soldiers–two millions sounds better than one million!–and then exclaiming with a proud, defiant air: New Germany can, in case of need, carry on several great wars at the same time!

This is a literal translation of the concluding sentence of a big press bureau article, which is now running through our national newspapers, and the real contents of which I have communicated above, such as to be read between the lines. Is it not a pretty situation for a victorious nation? And hopeful! Not yet is the peace concluded, which shall end the bloodiest and most barbarious war of modern times and already the comforting assurance is bestowed upon us from above, that this peace will, through the greed and ambition of our leading statesmen, be built on such unsound foundations, as to render a fresh outbreak (sooner or later,) inevitable, and, perhaps, the outbreak of several great wars to be waged by us simultaneously. When the old French Kings died, the courtiers, to show the eternity, the uninteruptedness of monarchy: used to call out le roi est mort! Vive le roi. The King is dead. Long live the King. Our press bureau scribes act somewhat similar to these courtiers, in proclaiming the eternity of war. War is dead! Long live war! One war is over–let us rush into fresh –great wars–several at the same time! And we found those scribes are right. For is not war the normal state of our society, which is based on discord, mutual hatred,–bellum omnium contra omnes–war of all against all? Does military war not correspond to this social war? Can our political body exist without war any better than our social body? Can our monarchies exist without militarism, and can our bourgeois society exist without it? Are not both resting now on the sword’s point, worshipping as their idol: yesterday a Louis Bonaparte, today a Bismarck–the men of blood and iron?

No hypocritical can’t, therefore: War was, war is, war will be, till this old world of ours is politically and socially reformed and reorganized throughout on the principle of justice. In the meantime, till the sham peace is concluded, the Prussians continue to remain in France, to levy black mail wholesale, and, in case of resistance, to set fire to houses and villages. If this was not written in Prussian papers, papers under the direction of the Prussian government, I could indeed not believe it. The worst is: such horrors can be told, without creating any visible indignation. This callousness of the public conscience, this lowering of the standard of national morality is the most baneful fruit of war. Oh! how right was Buckle, to say, that the height of civilization is to be measured by the hatred people bear to war and to men and things pertaining to it; and that love of war and admiration of warriors is an infallible proof of barbarity!

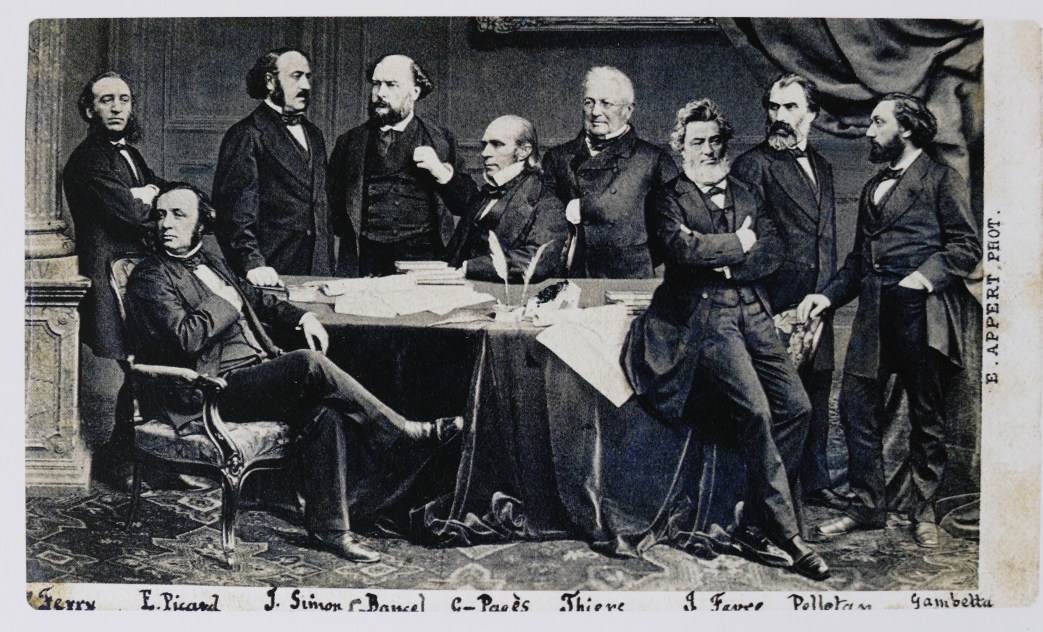

The particulars since came to hands, concerning the French elections, fully established the truth of what I said in my last letter about the comparative strength of the various parts. Much stress, I see, is laid in some quarters on certain oral declarations of Thiers’ emphatically reiterated a few days ago, to the effect that the Orleans family had by its countless political mistakes forfeited all dynastic claims, that monarchy in every shape had become impossible in France, and that the Republic, a moderate Republic, was the only form of government, promising stability, and offering guarantees against civil war. Maybe Thiers thinks so–maybe he does not. For the development of affairs this is of very small importance; and between the “moderate Republic” of Thiers’ and a “moderate Orleans” monarchy, there is so little difference, as to be imperceptible to the common Fortunately the Republic has other feet to stand upon, than the shaky thin legs of shaky (though twenty times elected) Thiers. The 225,000 votes for instance which Louis Blane has got in Paris, and the victory there of our friends Tolin, Milliere, and the most energetical of the men of action: that is a fact outweighing immensely all plans, schemes, intrigues, friendly or hostile to the Republic of Thiers and the whole collection of monarchical fossils converted to republicanism or not. Each hand that put one of these 225,000 votes in the ballot box will grasp a gun to defend the Republic, it she should be attacked!

In short, the republicans are strong enough to uphold the Republic. Only, and this is the sole point from which danger could arise, they must refrain from internecine, fratricidal strife. As the republicans are strong enough to uphold the Republic against all other parties, so the Republic can only be destroyed by the republicans. There is a deep gulph yawning between the honnetes or blue republicans, and the socialist or red republicans! But it is a gulph that can be bridged over, the epiciers, shopkeepers, from whom the blue republicans are recruited, not being like the Orleanistic higher middle-class-bourgeoisie–diametrically and irreconcilably antagonistic in their class interests to the working classes, who are socialists to a man. On either side everything must be avoided that could sow distrust; everything must be done to establish mutual trust to render political co-operation possible. The fall of the Republic of 1848 ought to be sufficiently impressive lesson. Shall silly fear of the red spectre drive the republican shopkeepers to massacre a second time the republican workingmen and their brothers, to massacre a second time the Republic, their common mother? Let them look the spectre in the face, and they will find out that it is but the baseless fabric of their imagination; and they will further find out that the social question is a stern reality, the grand problem of our age, to be solved peaceably, if the middle-classes, or at least the democratic majority of the middle-class the shopkeepers–assist the working classes, to be solved with slaughter and terrible revolutionary earthquake, if they oppose them.

On the other hand let the socialists distinguish sharply between the final aim and that which can be realized at the moment. At the Basle Congress the representatives of the French working men have most of them shown their practical sense, by voting against a resolution which they thought might produce a bad impression on the French peasants. I am confident they will show the same practical sense now, when an inopportune word, a hasty action would have infinitely more disastrous consequences, than could be apprehended eighteen months ago. Perhaps some French socialist reads this–he may be assured it is a friend that wrote it.

1. (Zoll Parliament in German.) This assembly had to deliberate on the customs and duties of the Zolleren, and consisted of the Reichstag for North Germany, and of Deputies elect ed expressly in the South Western Germany States. If the war of 1870 had not swept it away, it would have died of ridicule and ennui.

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

Access to PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-04-22/ed-1/seq-2/