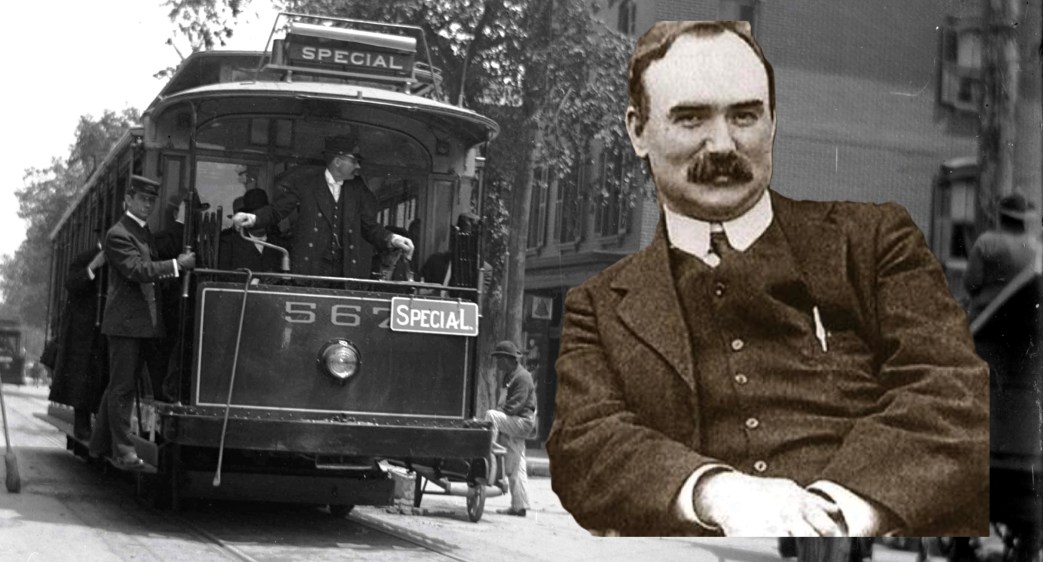

In this edition of ‘Notes from New York,’ Connolly relates his role in a Yonkers trolley strike for union recognition, where he attempted to win the workers from the A.F.L.’s pure-and-simple bureaucrats who had recently betrayed a New York City transit struggle.

‘Notes from New York’ by James Connolly from Industrial Union Bulletin. Vol. 1 No. 42. December 14, 1907.

Readers of The Bulletin may perhaps remember having read a short notice of a strike of trolleymen in Yonkers, New York, but there are a few details of the first day of the strike which have not yet been made public. These I now give as a double illustration of the correct attitude of the workers when unhampered by pure and simpledom, and the cool lying of A.F. of L. officials to secure their ends.

Previous to the strike the workers were unorganized. As a result, when the discontent which had been fermenting so long at last came to a head the strike committee waited upon the manager after the last turn of men came in to the yards in the middle of the night, and quietly presented their demands, intimating that if these were not acceded to not a man would go to work and not a car would leave the yards. Needless to say, the manager stood aghast at this revolutionary method of striking, accustomed as he was to see the pure and simplers give their employers three, six or even twelve months’ notice before striking (and incidentally give the employers three, six and twelve months to, secure scabs and generally to prepare for the conflict). He protested strongly against the proposal of the workers to take him by the throat in the same brotherly manner as capital generally fondles labor.

That, he imagined, was the holy prerogative of the capitalist. To force the laborer into a corner where, menaced by starvation, he would accept any terms offered him, is genuine freedom of contract, but to get the capitalist into a corner and try to squeeze him–this, gentlemen, you must perceive, was a highhanded outrage

Hence the manager pleaded for the strikers to return to work and appoint at committee to confer with him in the meantime. “Yes,” said one of the deputation, “and while we are working you will be securing scabs.” Such insolence! So they struck. It was a complete tie-up. Not a wheel turned that day, and for the time the capitalist was at his wit’s end. The spontaneous instinct of the workers had achieved a completer stoppage of industry than is usually achieved by “organized” pure and simple leadership.

But this complete tie-up was brought about by the strike of unorganized men: the only organized men who were connected with the company were the electricians and engineers who furnished the power from which the cars derived their motive force. These men were not directly in the service of the company, but of another company under contract to supply power. Of course, they remained at work. You see, they had a contract with their employers, and their employers had a contract with another company, and so, and therefore, and for that reason, d’ye see? they took a tight grip on their union cards and–scabbed it on the men on strike.

On the first day of the strike Fellow Worker Jacobsen, who lives in Yonkers, sent for me, and I took train at once for that city. The teamsters’ union had in the meantime sent a delegation at New York to bring up an A.F. of L. organizer to organize the strikers. I got in first, however, and presented by I.W.W. credentials and was given the floor. I am not in favor of organizing into the I.W.W. men who are on strike or who at the moment of organizing are talking strike. Therefore my remarks were mainly on the lines of how men educated upon industrial unionism would conduct such a strike, complimenting the strikers upon the spirit and method of their strike, especially in refusing to give warning to the bosses, and finished by comparing the wisdom of their course of action with that generally pursued by pure and simpledom.

My positive advice to the men, apart from the criticisms of the mistakes of trolleymen elsewhere, as in New York, was to besiege the powerhouse employes with deputations, not in their work, but at their homes, and to keep at them night and day until they left their positions and joined the men on strike.

The chairman informed me that the strikers had resolved before I came to organize into the A.F. of L. and had only given me the floor in courtesy. Then he called upon Mr. Jennings, of the Teamsters’ Union, to address the meeting. Mr. Jennings immediately launched into an invective against the I.W.W. and all its works and pomps, paring at the vials of his wrath upon my friend, Daniel De Leon, Eugene Debs, Haywood, Trautmann, and all our real or supposed leaders, and finally assuring the strikers that he would secure them the unequivocal support of his union, the A.F, of L. and of Mr. Mahan of the Amalgamated Street Railroad Employees. I inquired how it was that he could promise the support of his union to at strike in which they were only indirectly interested, whilst in the case of the longshoremen’s strike in the port of New York his union continued to work and handle the goods loaded or unloaded! by Jim Farley’s scabs. With undaunted assurance Mr. Jennings replied that the Teamsters’ Union had been ready and ever had volunteered to strike in aid of the longshoremen, but had been told it was not necessary, that the longshoremen had the situation well in hand. I have first-hand information that this was an invention, pure and simple, that the teamsters were asked to strike, but replied that they must stand by their contracts. Indeed, as A.F. of L. men they could do nothing else.

But before an audience of strikers was not the place to demonstrate this. As the men had made up their minds as to affiliation before I spoke, I, of course, left them, but as I went out, I gave them this nut to crack:

“Mr. Jennings says he will secure you the support of Mr. Mahan of the Amalgamated Street Railroad Employes, and of Mr. Gompers. Now, these two worthies are the very men who broke the strike of the subway and elevated men in New York by ordering them back to work on the ground that they had broken their contract and had not given their employers sufficient warning. How, then, will they treat you, who have given your employers no warning at all?”

I forgot to say that in one of his perorations Mr. Jennings linked together the names of Jesus Christ and Mr. Gompers as two great leaders of the common people. To the ordinary observer of things in the labor movement it would seem that, to use current slang, a “wise guy” named Judas Iscariot would have seemed a fitter comparison with Sam Gompers. But perhaps this would be an injustice to Gompers, for Sam no doubt looks upon Iscariot as a pitiful sort of scab. Iscariot scabbed for thirty pieces of silver, whereas Gompers’ price is–well, what is Gompers’ price, anyway!

There is a problem for W.J. Bryan: Does the high price Mr. Gompers receive over the thirty pieces of silver paid to his fellow-craftsman, Judas, bear any relation to the depreciation of silver and the inflation of currency by a gold standard? And if it does bear any such relation, is the relation that of 16 to 1, or what?

But to conclude the account of the strike. The men made a heroic struggle and the powerhouse employes continued to loyally serve the company, though unavailingly, and the pure and simple leaders finally entered into an arrangement with the company to return to work pending the settlement of the dispute by arbitration.

Then all the papers announced, “Victory for the Strikers,” “Recognition of the Union,” “Appointment of Board of Arbitration.” Thus, is “labor news” manufactured. The recognition of the pure and simple union was hailed as a victory for the strikers, despite the fact that they had no union when they went on strike and therefore could not have gone on strike to obtain recognition for it. The return to work pending discussion of their grievances was a victory, although they had been offered and very wisely rejected that before they went on strike at all.

It was a victory all right, not for the strikers, but for the employers and the pure and simple union. The latter had now a few hundred more dues-paying dupes, and the former could rest content knowing that their men were now organized in a union that could be trusted to prevent their taking their bosses by surprise again by striking at a moment’s notice. Henceforth if the Yonkers trolleymen strike they will first give the boss a few months’ notice, and due time to procure scabs and comply with all the requirements of the law, but between them the pure and simplers and the employers will take care that the contracts will not expire at or about election time. It is only a few hundred more of our class delivered over, bound hand and fool, to be preyed upon and their veins, sucked dry by the foul parasites that fatten upon labor.

That is depressing, and if you want the gloom chased from your minds, why, the remedy is simple: Buy tickets for our ball, the ball of the Industrial District Council of New York. Let us get together and dance; when the boss comes along in the workshop we have to do another kind of dancing to hold our jobs.

James Connolly.

The Industrial Union Bulletin, and the Industrial Worker were newspapers published by the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) from 1907 until 1913. First printed in Joliet, Illinois, IUB incorporated The Voice of Labor, the newspaper of the American Labor Union which had joined the IWW, and another IWW affiliate, International Metal Worker.The Trautmann-DeLeon faction issued its weekly from March 1907. Soon after, De Leon would be expelled and Trautmann would continue IUB until March 1909. It was edited by A. S. Edwards. 1909, production moved to Spokane, Washington and became The Industrial Worker, “the voice of revolutionary industrial unionism.”

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/industrialworker/iub/v1n42-dec-14-1907-iub.pdf