On an organizing trip for the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, Frank Crosswaith describes his visits to Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, and Albany.

‘Crusading for the Brotherhood’ by Frank Crosswaith from The Messenger. Vol. 8 No. 6. June, 1926.

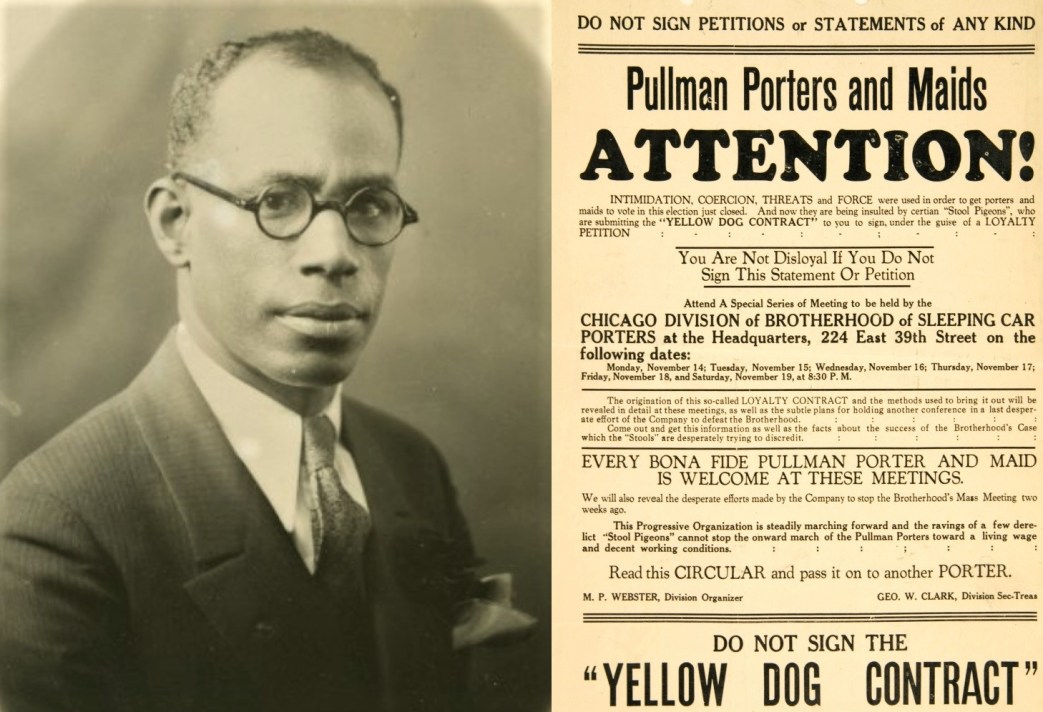

That a new Negro has arrived in the United States is admitted by every one who has been following the development and expansion of the Negro in the arts, and literature. Many people differ, however, in truly identifying this new Negro. Various writers and scholars have tried to locate him, but with very little success. What is new of the Negro in America, is not so much his classical adventures as is his gallant strides made in understanding the social system under which he lives and in a realization of the tremendous importance of economics in an effort adequately to solve what is loosely termed the “Negro Problem.” As an evidence of this truth the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters is the most outstanding example. The existence of this powerful economic organization will not alone affect the relationships of the white and Negro peoples of the United States, but will divide the Negro race itself upon the basis of their separate interest in the struggle to live. Already this is becoming clearer and clearer as the Brotherhood sweeps forward in its spectacular crusade to bring economic relief directly to the twelve thousand Negroes employed as Pullman Porters and Maids. In this regard it is interesting to students of the social sciences to observe that the most vicious and persistent opposition to the organization of these workers has come from some so-called Negro leaders and Negro institutions.

At midnight on March 12th, the writer in company with W.H. Des Verney, Assistant General Organizer of the Brotherhood, left New York City for a short trip in the interest of the Organization. Our itinerary called for stops to be made at Pittsburgh, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Detroit, Buffalo, and Albany, in the order in which they appear. Pittsburgh is considered one of the most solidly anti-union industrial centers in the eastern section of the United States. We found it living most scrupulously up to this reputation. But more than this, we found that the Pullman Company exercised no ordinary amount of influence upon the Negroes of Pittsburgh and upon the institutions supposedly belonging to Negroes. Negro churches and social agencies were particularly influenced to such a degree that for a time it seemed as though the Brotherhood’s message would remain undelivered in Pittsburgh. It required exceedingly agile maneuvering on the part of my colleague and I in order to overcome this influence and so accomplish something constructive among the porters there. The district is reputed to have about 300 to 350 porters. The men are governed by Superintendent Kaine. He is pictured by some of the local porters as a true personification of the czaristic philosophy. “I am monarch of all I survey; my rights there are none to dispute.” Like all men of this type, say these porters, he has surrounded himself with a few faithful hirelings to whom an appeal to race, to honor, or to those finer qualities to which the average man responds have little or no effect whatever, but whose conduct squares best with the old barbaric command, “Slave, obey thy master.” Some of the more manly and honorable porters in Pittsburgh are rigidly opposed to having Harry T. Jones as instructor of Pullman porters. It is common knowledge in Pittsburgh, however, that Harry T. Jones is very well liked by his immediate superior, because of “efficiency of service.” One porter said: “Why, Mr. Crosswaith, if we have chicken for dinner, that fact is known in the office of the Superintendent next morning. If we buy a decent rug for our homes, that, too, is immediately reported, and as a result of our efforts to brighten our homes, we are usually penalized.”

We were informed by a prominent social worker that a Negro institution, ostensibly for social purposes was being used as an agency for spying on the activities of prominent Negro agitators especially those with an economic program. One of the agents of this outfit, she said, had made several visits to New York where he attended the mass meetings of the Brotherhood, and that on one occasion she read his report and saw the writer’s name coupled with that of the promoter of the American Negro Labor Congress. Whether this bit of information is true or false, Pittsburgh still remains the ancestral home of “stool pigeons.”

It was only after we were successful in getting before the Baptist Ministers’ Conference of Pittsburgh and vicinity, composed of 150 ministers with a combined congregation of approximately 45,000 persons that we were able to overcome the opposition. The Conference adopted the following Resolutions endorsing the Brotherhood and exhorting Baptist Clergy and laymen everywhere to give the Pullman Porters all moral and financial support possible.

“Whereas, We, the undersigned ministers, representing the Negro Baptist Ministers’ Conference of Pittsburgh and vicinity, with 150 churches and a combined congregation of approximately 45,000 persons, after hearing the address of Frank R. Crosswaith, a representative of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, do hereby go on record unqualifiedly endorsing the gallant efforts being made by this group of Negro workers to strengthen their chances in the struggle to live by organizing a union. And, Whereas, we endorse this movement because we feel that in organizing a union, through which to protect their interest, they are doing no more than workingmen of other races have done and are doing. We also endorse this movement because we believe that if these men succeed with their program their success will tend to encourage race workingmen everywhere to harness their producing powers for the purpose of improving their economic, social and educational status, making generally for the betterment of the human race. And, Whereas, we unhesitatingly condemn those who, being devoid of vision and race pride, have lent their time, ability and their position to misrepresent this great movement and thwart its progress, especially those ministers of the gospel who, in this instance, have substituted the Cross of Christ for a cross of gold in order that they might stand with those who would keep this body of Negro workers from exercising their inalienable right to life, liberty and happiness. Therefore, be it Resolved, That we, the Baptist ministers of Pittsburgh and vicinity in conference assembled, do hereby pledge unstintingly our moral and financial support to the manly and courageous efforts being made by the Pullman porters to organize themselves into a union, to be known as the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. And we appeal to our brethren everywhere to aid them in every way possible.”

A similar attempt was made to appear before the Washington Conference of the M.E. Church, which was presided over by Bishop Claire, but we were unsuccessful in doing so. Evidently, these men of God (?) would have nothing to do with us. The writer personally appeared at the Conference on two occasions and presented his card with a request for the privilege of addressing the gathering on the matter of the Brotherhood. These requests were absolutely ignored by Bishop Claire who was in the chair at the time. Not only were we ignored, but those who controlled the publicity of the Conference saw to it that all other visitors were announced in the press except the representatives of the Brotherhood. No doubt, had a Pullman official appeared at that conference, he would have been permitted to speak, and the learned ministers would have considered themselves rendering a great service to God and their race. Not all the Negro ministers in Pittsburgh, however, have pawned their souls to wealth and greed. For instance, there is the Rev. Dr. C.A. Jones, Pastor of Central Baptist Church and Rev. Dr. H.P. Jones of Euclid Avenue Church. These two men, with a few others, stood out among the ministers of Pittsburgh like a beacon light at night on a dark and storm-swept sea.

Nevertheless, after spending considerable time there, we left with a goodly percentage of the men having signed up as members of the Brotherhood. It might be well here to state that since leaving Pittsburgh, the men of that district have been steadily coming into the Organization.

In Cincinnati conditions were a little more pleasant. There we were fortunate in being in a city where the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America has a strong organization. These white working men, without being requested to do so, turned over to us their large assembly room, located in the Brotherhood of Railway Clerks Building for our mass meetings. It is said to be the first time that Negroes were ever in the building in any other capacity than that of servants. We held two meetings there, which, while they were not overflow meetings, were of tremendous propaganda value to our Organization, and we enrolled quite a number of local porters before our departure.

Detroit proved to be a paradise. Meetings were held there both mornings and evenings, and they were all well attended. There was not a single meeting at the close of which the Brotherhood was not stronger by six to thirteen new members. Cleveland was the next stop, and proved equally as fertile as Detroit, if not much more so.

The Aldun Hotel (hole in the wall) in which our meetings were held witnessed a constant stream of proud porters flowing forward to join the ever-swelling ranks of the Brotherhood. The white newspapers gave us splendid publicity. In Buffalo we conducted our meetings, two each day, in Evans’ place, just opposite the railroad station. These meetings were well attended, and like those in Detroit, and in Cleveland, took on, in many instances, the appearance of gigantic mass meetings. At the close of each meeting my colleague and I were literally swamped with applicants. Albany not having very many porters left for us to enroll, our visit there was very short. We returned to New York City on the night of April 14th, after covering nearly 2,000 miles of territory. We delivered together almost 100 speeches in the cause of the Brotherhood in particular and labor in general. The trip on the whole was a splendid triumph for our cause; it convinced us thoroughly of the fact that the Negro workers of the United States are at last awakened to the important part played in their lives by the economic factor, and that truly a new Negro faces America; that he is ready for the gospel of economic emancipation, and that the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters is symptomatic of this fact. The spiritual and educational gains of this trip is beyond my pen adequately to describe. Sufficient to say, however, that through the existence of the Brotherhood the Negro in America in particular and the workers generally, are spiritually richer for our being.

The Messenger was founded and published in New York City by A. Phillip Randolph and Chandler Owen in 1917 after they both joined the Socialist Party of America. The Messenger opposed World War I, conscription and supported the Bolshevik Revolution, though it remained loyal to the Socialist Party when the left split in 1919. It sought to promote a labor-orientated Black leadership, “New Crowd Negroes,” as explicitly opposed to the positions of both WEB DuBois and Booker T Washington at the time. Both Owen and Randolph were arrested under the Espionage Act in an attempt to disrupt The Messenger. Eventually, The Messenger became less political and more trade union focused. After the departure of and Owen, the focus again shifted to arts and culture. The Messenger ceased publishing in 1928. Its early issues contain invaluable articles on the early Black left.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/messenger/v8n06-jun-1926-Messinger-RIAZ.pdf