Founding French Communist and later left Socialist Andre Morizet on the first years of the ‘Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution, Speculation, and Crimes Committed by Officials in the Exercise of their Functions.’

‘The Cheka’ by Andre Morizet from Soviet Russia (New York). Vol. 6 No. 9. May 15, 1922.

SINCE the November Revolution, since the events that I have just traced, Russia, moving toward the establishment of a real Communist regime, has been living under the rule of the “Dictatorship of the Proletariat”.

“The Dictatorship of the Proletariat”—this is a phrase that has caused oceans of ink to flow in all the polemics that have been written on Revolutionary Russia.

As if this were a new idea! As if Marx and Engels, when they issued the Communist Manifesto, had not already pronounced these words in 1848! As if all the parties which have declared themselves as Marxian parties for the last sixty years had not always inscribed these words on their programs!

Seriously speaking, is it possible to imagine a transition from one regime to another without a period of Provisional Government? When we are not changing only a political personnel, as in the revolutions of the past, but the very bases of the social order, as is proposed by our party, is it possible to escape understanding that a seizure of power—which is what we call “revolution”—will be followed of necessity by a period of transition in which men enjoying the confidence of the victorious proletariat will exercise authority with dictatorial methods?

It should be unnecessary to discuss this point. I know very well that it is less the principle of dictatorship that arouses discussion—except in some anarchist circles where certain words arouse terror—than the application that is said to be made of this principle.

“Red Terror” is said to reign in that country, according to our respectable press. The Bolsheviks—it is alleged—have been drowning the country in blood. The Cheka, the terrible Cheka, is said to be committing crime after crime. And it is declared that in the Soviet Republic no one lives except in constant terror, under the threat of impending persecutions.

All popular movements, even those of very short duration, even the most peaceful, have been accused of cruelty. The same legend has been spread by the reactionaries concerning all of them. In 1848 it was the “soldiers of order” who were sawn to pieces between two boards, while in the Commune of 1871 it was the “petrol euses”; there is hardly a calumny that has not been resorted to by those who had on their consciences the June assassinations or the massacres of the month of May.

It is hardly surprising that the Bolshevik Revolution should suffer the same misrepresentations as its predecessors. The Russian emigres and the conservatives of all countries have money with which to buy newspapers, and the hatred of Communism predisposes the imbeciles of all the world in favor of their theses.

The Bolsheviks have executed people. Indeed! For four years there has been one plot after the other, insurrections and more insurrections. As each attempt at invasion was put forth, hands were stretched out from the interior to aid the White adventurers. And Russia has had to defend herself.

In July I myself saw at the fortress of Peter and Paul, on the day when I paid a visit to this sinister place in which the Decembrists were hanged, and where so many Nihilists died in the dungeons of the “Ravelin of Alexis”—I saw soldiers leading out dozens of men that the Cheka had arrested.

And what of it?

The question that should be put by serious minds is not merely the question as to whether blood is being shed. Blood flows in wars; it flows in any revolution. The question is to learn whether it is shed uselessly, whether the inevitable duty to defend one’s achievements may not cover abuses, revenge, or excesses.

I have come to the conviction, after having had conversations with men extremely worthy of faith, that the story of the “Red Terror” is one of the most shameful mystifications prepared by the adversaries of Communism, and that the Bolsheviks, in the matter of repressions as well as in other matters, have done only what was expedient and feasible with the means and the elements at their disposal.

The organization created by them, the Chrezvychaika, or Extraordinary Commission, called for short Cheka, bears the full name of: “Extraordinary Commission for Combating Counterrevolution, Speculation, and Crimes Committed by Officials in the Exercise of their Functions”.

Its jurisdiction is therefore not limited to the suppression of plots. The Cheka collaborates actively in the work of economic reconstruction of the country. It searches for stocks of raw materials or goods that have been hidden, supervises the observation of labor regulations, and prosecutes unscrupulous functionaries.

These duties occupy this body more and more, as the task of defending the regime decreases in importance. And it may be seen from the example that I cite in the chapter on “Electrification”, that its interferences are of extraordinary value.

There is an Extraordinary Commission connected with the Council of People’s Commissars; this is called the Ve-Cheka. There is also such a commission attached to the Soviet of each province. Each has at its head a more or less numerous presidium, which consists, in the case of the Ve-Cheka, of fifteen members, appointed in this case by the Council of People’s Commissars, and in the case of the provinces by the Executive Committee of the Soviet.

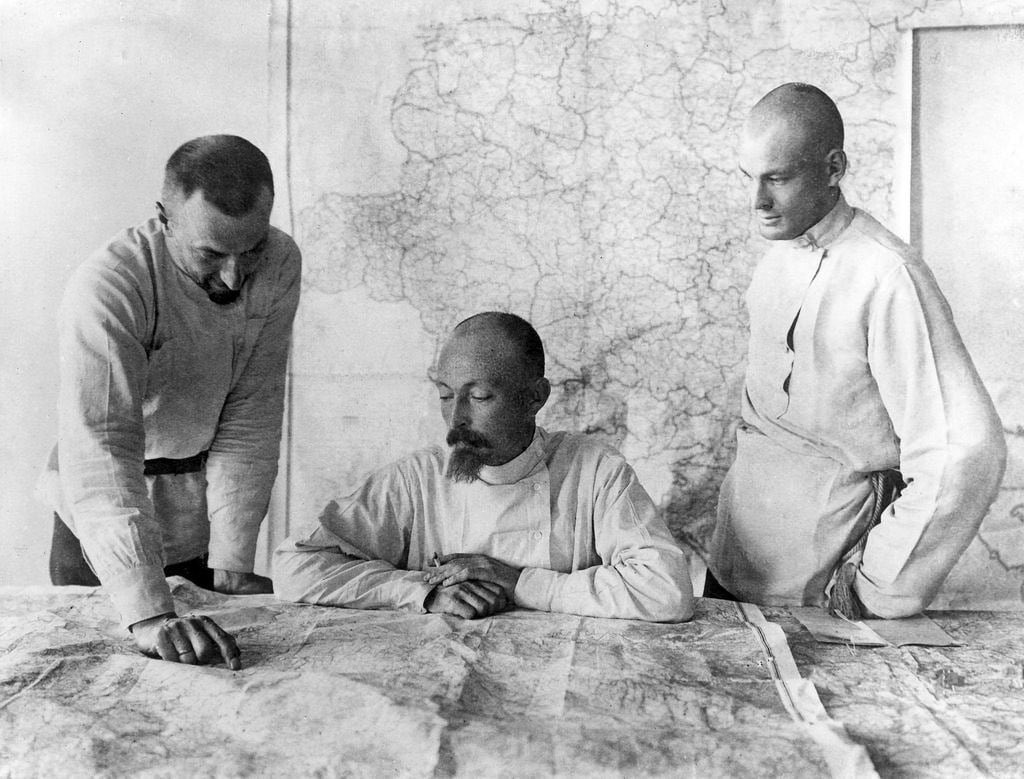

The presidium itself pronounces judgment in the cases submitted to it by the preliminary judsres,1 or it refers them to the revolutionary tribunals when it is desired to give publicity to such cases. The members of the presidium are well-known militants of unquestioned reliability. The president of the Ve-Cheka, Dzerzhinsky, is an ascetic of whom it is said that when he was a prisoner in Germany he sought out the most repulsive and disagreeable tasks in the prison in order to show that it is the duty of the Communist to set an example of service wherever he may be.

He is People’s Commissar for the Interior, President of the Donets Commission, and in charge of Railroad and Water Transport, and is only titular head of the Ve-Cheka (All-Russian Extraordinary Commission). His functions in the latter position are discharged by Unschlicht, formerly a member of the Military Council of the western front, an old party militant, universally esteemed.

As for the Provincial Chekas, the following figures will show how they are constituted. In 1920, a conference of their presidents and vice-presidents was held at Moscow. Of the 69 who were present, there were 45 workers, 13 peasants and 11 intellectuals. All were party members and 28 of them had already been party members under the Tsar.

It is not among this personnel of devoted revolutionists that you will find the undesirable elements. Unfortunately, however, the subaltern functionaries cannot be recruited quite so scrupulously. To be sure, there is a large proportion of Communists, but there are also those that are not Communists.

We must not forget that, as Zinoviev points out in the address delivered to the Halle Congress, before the establishment of the German Communist Party, the Bolsheviks lost more than 300,000 of their number in the wars that they had to fight and that their old guard has to a great extent disappeared; that they are not numerous enough to fill all positions themselves and that they have frequently to resort to Communists of recent date, who had joined them in order to profit by the advantages of power, or to old officials of the former regime. The fact that there are among them, among the preliminary judges, the secret agents, the employees of all ranks, certain persons capable of occasionally abusing their birthright, cannot be doubted when we remember that the Extraordinary Commission itself has frequently had dozens of its own agents shot.

In spite of the inadequacy of its ranks, which is due to the general low standard of popular education, to which those abuses which have really occurred must be assigned, we could not in full justice form that opinion of the Cheka which one would hold if one should put faith in all the fables that have been handed out.

To judge by the sheets published in Europe by the Whites, one might imagine that the Bolsheviks have shot people by hundreds of thousands from one end of Russia to the other. It is a long wav from this fiction to reality.

Pierre Pascal, of whom I have already said that his splendid inteprity is as great as his critical intelligence, in 1920 published statistics on the supreme penalties imposed during the years 1918 and 1919.2

“Throughout Soviet Russia,” writes Pascal, “in the course of two years of revolution, after nearly 500 counter-revolutionary plots of all kinds and 50 bands of brigands have been exposed by the Extraordinary Commission, after the systematic campaign of murder in 1918 against the most well-known Communists, after the attempted espionage and treason by thousands of former policemen, army officers, landed proprietors, with full warfare in progress both on the border and in the interior, in the midst of perpetual mortal danger to the Soviet Republic, the Extraordinary Commissions executed 9641 individuals, and the revolutionary tribunals passed less than 500 sentences of death, most of them being conditional sentences that were never carried out.

“But, to judge the matter properly, we must consider these figures scientifically. It appears that of the 9641 persons shot by the Extraordinary Commissions, about 2600 were common law criminals, big speculators, dishonest officials, and particularly dangerous and incorrigible bandits, the sad remnants of a poorly organized society, more dangerous in a troubled period than at any other time, whose merciless extermination was demanded by the requirements of revolutionary order.

“There remain then 7068 spies, organizers and other active counter-revolutionaries who were shot in all the territory of Russia in the course of these two years of civil war.”

Of this number of executions, 5513 took place in 1918, and only 1555 in 1919.

7000 political executions in two years, while Russia was being attacked from all sides!

I have tried to obtain the corresponding figures for the two years that followed, but have not been able to get anything precise. Approximate estimates, have been furnished me by men whom I consider worthy of confidence. The highest of these estimates would give the figure of 12,000 or 15,000 for the four years of the Revolution.

Of course even this figure is cause for regret. We may of course deplore that even a single individual should have been shot. But if we make any pretense to impartiality, we must consider that Revolutionary Russia had but one choice, namely the choice between victory and death, and that the total population of the country is 130,000,000.

To those who do not wish to make any effort to be impartial, the Bolsheviks may always reply by indicating the number of victims that were massacred by their enemies. I shall give some figures on this head in the chapter entitled “Civil War”.

As for my compatriots, who are too much occupied in vituperations against “Red Terror”, forgetting the “White Terror” which in every case far exceeded the other, I shall limit myself to reminding them that if the Soviet Revolution shot twelve or fifteen thousand Russians in four years, the Versailles Army in 1871 laid low 34,000 Communards on the Paris pavement in eight days.

The following chapter on Dictatorship and Red Terror is a portion of a book entitled “In the Land of Lenin and Trotsky—Moscow 1921” written by Andre Morizet, with a preface by Leon Trotsky which appears elsewhere in this issue.

NOTES

1. The author here uses the French word jures d’instrucsion, for which there is no parallel in Anglo-Saxon countries. The judge d’instruction in France draws up indictments for the courts proper. This judge has no executive function, but only the function of transmitting information.

2. In Russie Rouse, by Pierre Pascal, a pamphlet published by Humanite in 1921.

Soviet Russia began in the summer of 1919, published by the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia and replaced The Weekly Bulletin of the Bureau of Information of Soviet Russia. In lieu of an Embassy the Russian Soviet Government Bureau was the official voice of the Soviets in the US. Soviet Russia was published as the official organ of the RSGB until February 1922 when Soviet Russia became to the official organ of The Friends of Soviet Russia, becoming Soviet Russia Pictorial in 1923. There is no better US-published source for information on the Soviet state at this time, and includes official statements, articles by prominent Bolsheviks, data on the Soviet economy, weekly reports on the wars for survival the Soviets were engaged in, as well as efforts to in the US to lift the blockade and begin trade with the emerging Soviet Union.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/srp/v6-7-soviet-russia%20Jan-Dec%201922.pdf