The Living Newspaper, a radical staging of the news, was taken from the Russian experience and became popular in the 1930s. One of the originators in the U.S. tells of its development and its most recent production, 1935, looking at that year’s events.

‘The Living Newspaper’ by Morris Watson from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 3 No. 6. June, 1936.

The current edition of the Living Newspaper at the Biltmore Theatre, 1935, recounts various happenings of the year for which it is named and represents a deliberate experiment in the matter of presenting news visually.

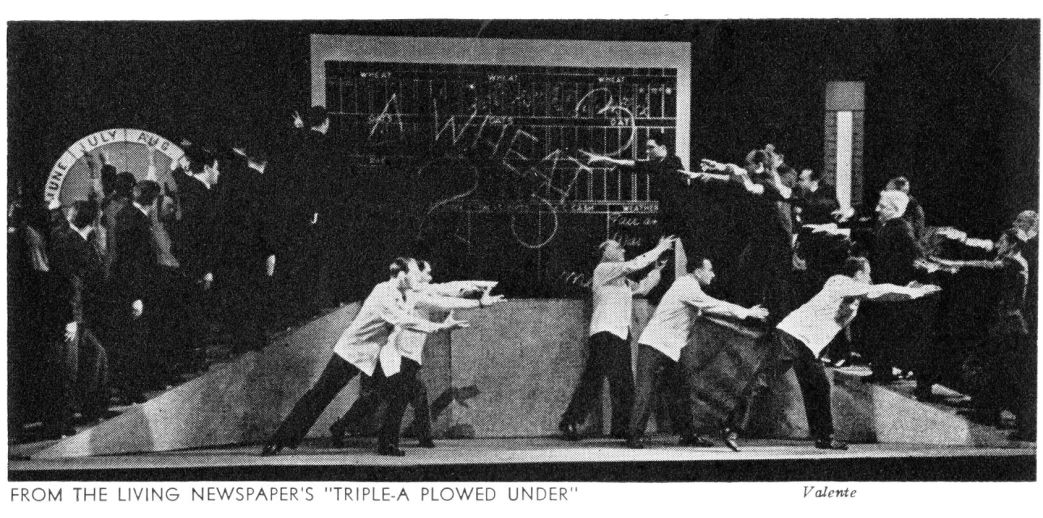

The Living Newspaper’s first offering, Triple-A Plowed Under, took a single theme and developed it along news lines and actually was more pamphlet than newspaper. In 1935 unrelated items are presented on the same program, and the temper of the year, rather than the history, is stressed.

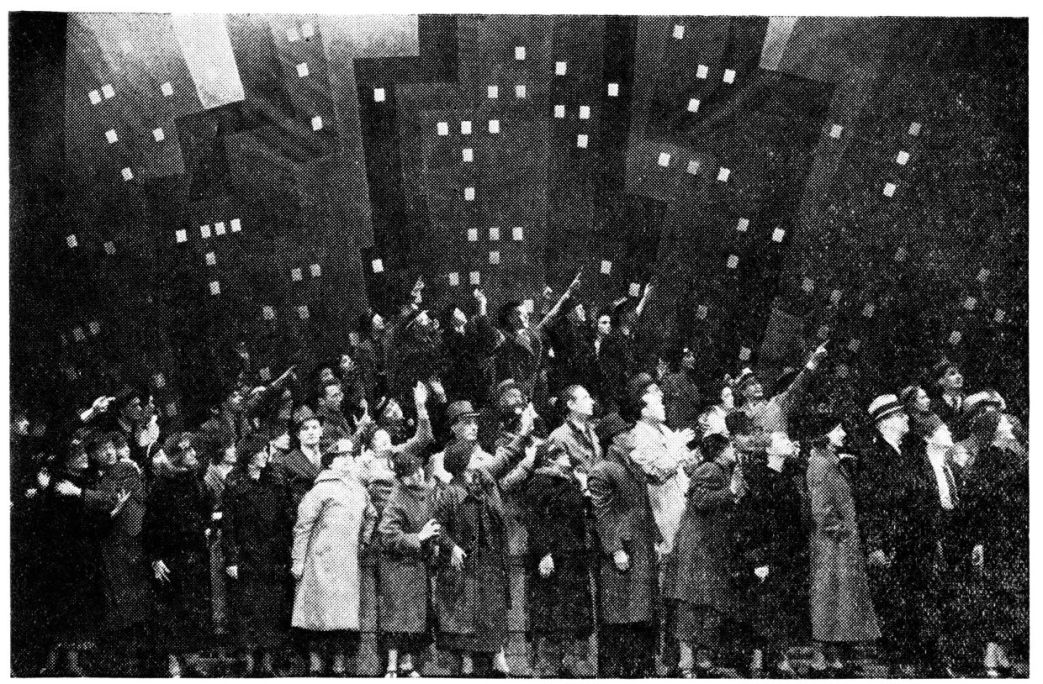

The edition opens its story at 11:58 p.m. of the last day of 1934 with a crowd of merrymakers at Times Square. The commentator asks if they remember Hindenburg, John L. McGraw and Marie Curie who died in 1934. And do they remember the assassination of King Alexander and the burning of the Morro Castle? Midnight comes with a blast of noise.

“Make news!” the commentator pleads. Twelve representatives of the Great American public get into a box to judge the events and the Voice of the Living Newspaper quickly announces January 2, the opening of the trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for the kidnaping and murder of Baby Charles A. Lindbergh, Jr. A Flemington, N.J., ballyhoo man proudly conducts a crowd of curious through the courtroom and tells them where Gloria Vanderbilt, Big Nick Cavarro and other celebrities parked themselves for the trial. The trial goes on with the crowd rushing for seats, with reporters quarreling over the purchase of exclusive stories from the principals. Betty Gow is called. “I couldn’t hear the baby breathe,” Miss Gow testifies. As she speaks the courtroom blacks out, a spot comes up on a stylized witness stand in the center. The stand becomes a crib. She feels over the covers. Her expression becomes one of horror. She hesitates an instant. Then she screams: “Colonel Lindbergh! Colonel Lindbergh!” and rushes off. “Jafsie” Condon comes on to testify. But he does not testify. He acts out what he has to say and the mysterious “John” of Van Cortlandt Park and the cemetery helps him. The spotlight turns to an eerie green. Leaves rustle. “John” sits with the elderly Bronx pedagogue and asks: “Would I burn if the baby is dead?”

Thus the technique of reporting a trial visually without merely reproducing it on the stage in a word-for-word manner.

Next comes a scene that violates all the rules of dramatic writing. But the Living Newspaper is a combination of newspaper and topical revue. It is reporting the passage of the Wagner-Connery labor disputes bill in the terms of an actual case. A young lady appears to testify before an examiner for the board. Her words become reality. “They shut off the power and made us all go to a big room,” she starts. She is talking about the Somerset Manufacturing Company of Sommerville, N.J. The curtain opens on a bunch of scared young girls and reveal the lengths to which small New Jersey towns will go to keep America safe for the exploited open shop. The episode ends with another piece of testimony acted out. One of the young ladies finds her pay is short. She goes to the office girl. She’s right. Her pay is short. But wait that’s the book for the NRA code inspector. According to the book she gets paid by, the miserable wage she got is all she had coming. No climax. The critics call it anti-climax. The boys of the fourth estate who edit the Living Newspaper are just telling a story for what it is worth. The scene may lack the customary punch expected at the end of a dramatic sketch. Anyone viewing it, though, should be able to see why labor needs some legal protection.

That the scene should have a “wallop” at the end may be a valid criticism. I’m not saying that it isn’t. The usual news story is written with the punch at the top. We newspapermen are newly wedded to the theatre. We have a lot to learn about each other. A dozen more editions should put us in step. The stride may surprise us.

A sop to humor follows the labor problem in 1935. Bugsy Goldstein is sore as hell. Officials have re-rated the public enemies and he’s only No. 6. Just a flash. The Great American Public plays a Giants-Dodgers ball game from its bunting-bedecked jury box. The scene means nothing to me because I never saw the Dodgers play. I can’t take sides here. The fans laugh like hell, and that makes it a good item for the Living Newspaper’s sports page.

Barbara Hutton gets married. This time to a count. The Living Newspaper falls back on the manner in which Miss Ruth McKenny handled the story for the New York Post: the manager of a Woolworth five-and-ten would be glad to let the Post photograph one of its workers who also was to be a bride that day–only, Miss Hutton might not like it! The next scene makes its own comment on the human race. William Deboe is hanged at Smithland, Ky. Folks turn out early to get good seats. Deboe was convicted of rape. He points to his accuser and says: “If I had five hundred dollars I wouldn’t be here, she’d a taken it.” What a thing to say! “Not if you offered me a thousand,” she comes back. A preacher intones the Lord’s Prayer. “Peanuts, Popcorn, Crackerjack,” yells the candy butcher. So far as we could determine, the scene is staged exactly as it happened. Two minutes before the curtain went up on opening night the actor who plays the preacher became convinced the Living Newspaper was poking fun at the Lord’s Prayer. He said he wouldn’t go on! We had to explain the idea.

Under the general heading of “Trivia” comes the case of the prisoner who was forgotten, who served eighteen years of a five year sentence, and the man who advertised that he found a lady’s purse in the backseat of his automobile. He was willing to pay for the ad himself if the owner would explain the matter to his wife who couldn’t imagine how the purse got there. A laugh.

The Voice of the Living Newspaper sweeps through the mention of several other headlines of 1935 and then Dutch Schultz comes on the scene–to beat the law, to die at the hands of the mob. The Great American Public discusses matters, not too relevantly. Then, Huey Long manipulates his legislators like puppets and swaggers on to his assassination. The legislative scene is stylized. It becomes a living cartoon and through it the Living Newspaper learns that it can pack potency into its editorial page.

The Great American Public again–to disagree on whether the assassination of Huey Long was a national crisis, and wind up by being indifferent to the whole matter.

In 1935 Jeremiah T. Mahoney and Avery Brundage argued about American participation in the Olympic games at Berlin. “Sport must confine itself to the affairs of sport and no other,” says Brundage. The Living Newspaper reports the incident, and illustrates sport as it is practised in the land of the Nazis. The best tennis player is removed from his team because he is a Jew. A Polish-Jewish soccer player is killed. A Catholic swimmer is stoned. The Living Newspaper doesn’t say anything is right or wrong. The audience does pretty well in making its own decision on the matter. I know of no way to censor hisses.

John L. Lewis makes a plea for industrial unionism. President William Green of the American Federation of Labor is adequately quoted. The Living Newspaper tries to illustrate the argument. No kick there.

The China Clipper flies from Asia to America in 62 hours for the sake of commerce. A thriller, and another experiment. The Living Newspaper is feeling its way.

Angelo Herndon in jail with a “mercy” sentence of 18 to 20 years on the chain gang.

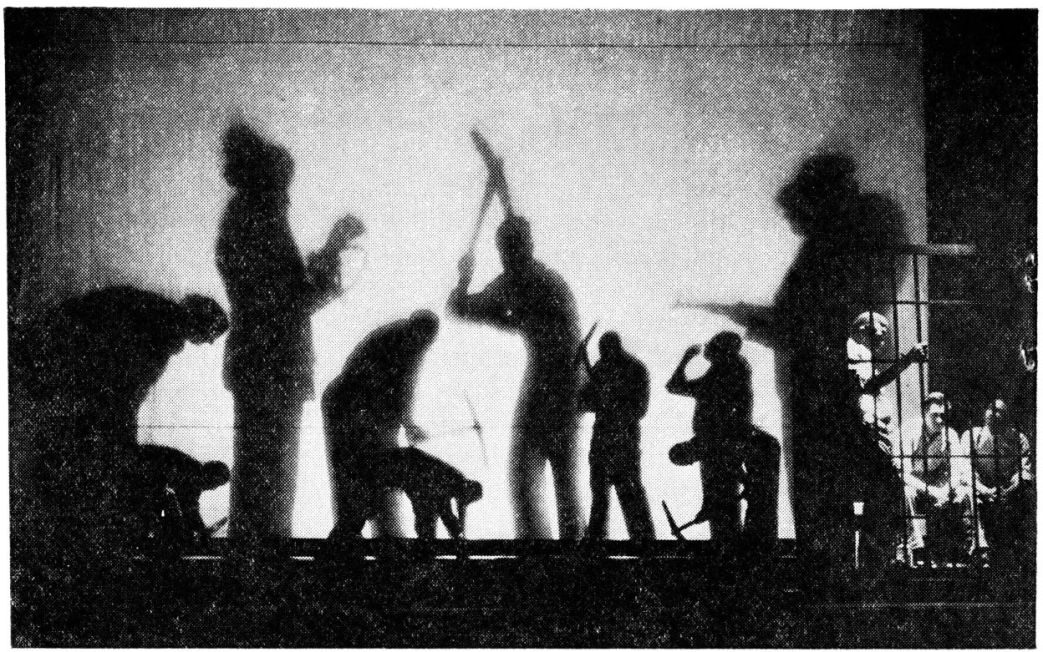

“That’s sho’ death,” says another prisoner who spent six months on a Georgia chain gang. Here a test of visual reporting. The prisoner stands in the cell and describes the horrors of Georgia torture.

The lights on him dim. The curtains open slowly and the audience gets a vivid glimpse of what he is saying. Silhouettes against a red light wield picks on a road. Over them hover the ominous, 20-foot high shadows of guards, rifles and whips held in position of “ready.”

“Ef yo’ cain’t stand it no mo’ and drop in yo’ tracks that ol’ whip come crackin’ down agin and somp’n make yo’ get up and raise a pick and drop a pick agin,’ the prisoner says. The silhouetted whip cracks.

The crowd is in Times Square again. Horns are tooting. Bells are ringing. Happy New Year! Welcome 1936.

It is difficult to compare this kaleidoscopic report of the year’s events which lent themselves to staging with the Living Newspaper’s first edition, Triple-A Plowed Under which tied the plight of the farmer to the plight of the city man and disturbed the mental processes of those who saw it. In other words, it made people think. 1935 hasn’t as much of that virtue, and it is open to a great deal more criticism. Each of its scenes is likely to be judged from a purely theatrical standpoint. They cannot, as did the scenes of Triple-A Plowed Under, flow into each other, contributing to another. Many times lately I have been asked: “Whose idea is the Living Newspaper?” The answer is: “I don’t know.”

The business of presenting news on the stage has been tried before–in vaudeville, by workers’ clubs, in the Workers’ Laboratory Theatre of New York and elsewhere. I also have hearsay evidence that Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur once toyed with the idea and that similar enterprises flourished for a time in Berlin and Moscow.

Whatever the idea behind the Living Newspaper in the beginning, circumstance and influences of one kind and another have modified it. A literally rough estimate of it at the moment would be: “Combine the newspaper and the theatre and to hell with the traditions of both.”

My own connection with the enterprise was an accident. Last October the Newspaper Guild of New York was looking for some way to absorb a few of its unemployed in the newly formed Federal Theatre Project. The Guild’s unemployment committee went to Elmer Rice, then the Regional Director for New York.

Rice suggested that a Project be formed to present news on the stage. The committee began looking for some one to head the project. The first I heard of it was when I was asked if I knew of any one who would fit the job. I didn’t. The heavy hand of coincidence entered the plot at this point and I found myself “at liberty.” To cut the corners on this explanation, there was thrust upon my shoulders the task of organizing the project.

I was greatly excited by the idea. For many years I had been covering living drama and visualizing it in terms of the stage. The amazing thing about the Living Newspaper is that it was so late in coming. The explanation may be that newspaper men have been timid about barging into the theatre and theatre men have been bound by too many traditions. There has been plenty of friendly conflict between those of us in the Living Newspaper who are of the fourth estate and those who are of the theatre.

Elmer Rice lent a vigor to the Living Newspaper which still is apparent. In the beginning we thought we would dramatize current news, it never occurring to us at the moment that the current news at hand was likely to be very weak stuff. The Living Newspaper staff of dramatists began culling the papers and writing for all they were worth on such items as “Tart Shoots Lover,” and “Robber Seizes Jewels of Movie Queen.” Rice’s criticisms resulted in a complete reorganization of my own news sense. Rice said things were going on in the world and he thought we ought to talk about them. I agreed. He thought of things that affected peoples’ lives and happiness and he didn’t care if we stepped on a few toes and made somebody mad.

Armed with this moral backing, we decided to dramatize that part of the news which was controversial, hence current when we reached the stage with it. In part this decision was based upon our disillusionment over the length of time it took the government to purchase equipment for the theatre, since it became apparent that any news item which had the value only of timeliness would be valueless by the time we could get it to the audience.

We lost no time in changing our direction. We launched into Ethiopia. Here unadorned fact became so powerful that federal officials were alarmed. Sympathies were bound to be with Ethiopia. This was not our fault. There was not the slightest bit of editorial shading in the script or direction. If the facts had been such as to glorify Mussolini and to make a villain of poorly represented Ethiopia, the subsequent course of the Living Newspaper might have been different.

The high command of the WPA made the presentation of Ethiopia impossible. The ruling was that under no circumstance were we to present any head of a state or foreign cabinet minister on the stage. Rice, in resigning over this censorship, declared that to present Ethiopia under this ruling would be like presenting Hamlet without Hamlet. We were about to open when the Washington decision stopped us. We were left with a large, demoralized acting company.

“Science” was suggested as a good, safe subject for the next show. It was quickly rejected. We had ready a script on the “Southern Situation.” It dealt with lynching, share-croppers and the several social struggles now going on in the south. Rightly or wrongly we compromised. We offered to do the Agricultural situation. With little in the way of facts to go on, several of the executive staff of the Living Newspaper literally wrote like hell on a Sunday to have a script ready on the following day so that the acting company could be immediately put to work. We wrote and rewrote Triple-A Plowed Under up to the day of its opening. The last scene, for instance, already revised five or six times, was completely rewritten the day before opening.

There were many predictions and few of them favorable for Triple-A Plowed Under. One director connected with the Living Newspaper declared it was “breakfast food” and quit his job rather than be connected with it. Some theatre people said it violated all the rules. An official from Washington saw a dress rehearsal and said it was “dull.” It was my own opinion, and it still is my opinion, that there exists a large potential audience of the theatre composed of people who are thinking, and who want to think more of the vital social changes which are going on in the world, and that Triple-A Plowed Under, with all its inadequacies as a theatrical production, came nearer to satisfying this need than any fictional play I have seen.

From time to time in the preparation of scripts many interesting and controversial elements arise, elements which would occur neither in the writing of a newspaper story nor in the preparation of a straight sketch or one-acter for the commercial theatre. Since the medium of the Living Newspaper is a combination of both, the predominance of one force over the other is frequently a moot matter which finds dramatist ranged against reporter on the question of which is more important and what leeway can be taken to make a yarn sustained on the stage. For instance, in the sketch about Huey Long in 1935 which is divided into three lightning scenes, it was felt that nothing could top the second, the puppet sequence, in which Huey conducts the legislature on strings. Yet the newspaper boys felt and insisted that the assassination was the news. The dramatists insisted that on the stage it was anti-climax. Both were right.

Research on the Living Newspaper requires a tabloid’s appraisal plus Sunday supplement’s coverage of facts. More than that, it presupposes an ability to discern implications, and to catch those small items which may have dramatic value.

Inevitably, the Living Newspaper’s technique is compared to that of the March of Time movie and radio programs. The difference between the two is essentially the point of view. March of Time is put out by a rich magazine and a rich advertiser. The Living Newspaper is written, edited, staged and acted by people who struggle for their living. It is bound to catch the flavor of that struggle. What it puts on the stage is the combined effort of a group trying its best to compose its differences and march in one direction. So far, there are no stars. I hope there will be none. Seldom is the audience conscious of any individual.

If the Living Newspaper is to grow into a vital force of great worth to the community it must not only continue to be the effort of a group but it must be free of every vestige of official censorship.

Its editors and its actors must be free to work out their own problems. A step toward this desirable state of affairs would be the divorce of the Federal Theatre Project from the WPA. So long as it is a part of the WPA it will be subject to petty and unfair attacks from those reactionary forces which see red in every letter of relief.

Is it too much to ask that the government grant a straight subsidy for something for which the community is hungry?

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n06-jun-1936-New-Theatre.pdf