Hugo Eberlein reports to the founding Congress of the Comintern as representative the Spartakusbund in a historic document of our movement. A founder of the Spartakusbund and the Comintern, Eberlein (R. Albert) was a leading figure of German Communism in its first decade. Eberlein had been youth leader and figure in the left of the German Social Democratic Party for a decade before the war. He would be elected to the Reichstag as a Communist in 1921, he was associated with the ‘conciliator’ wing (led by Ernst Meyer and favoring an alliance with the Socialists and against the ‘Third Period’ social-fascist/red unions positions) of the German Communist Party. Arrested after Hitler took power, he fled to France on his release where he worked for the Popular Front. Going to the Soviet Union in 1936, his past associations with Rosa Luxemburg and the ‘conciliators’ ensured he would be a target of the Purges. Arrested in 1937 and imprisoned, he was shot on October 16, 1941. Rehabilitated, Eberlein was seen as an anti-fascist hero in East Germany where his son, Werner Eberlein, was a leading SED figure until 1989.

‘Report from Germany’ by Hugo Eberlein from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 2. June, 1919.

As late as November 8th 1918 even the adherents of the independent social democrats declared it impossible that Russian conditions could ever arise in Germany, that is to say, that there wound over be a revolution in Germany. Yet as early as November 9th the old structure of the capitalistic regime collapsed. As early as November 9th we had the very thing in Germany, that up to that moment had been criticised so severely with regard to Russia, the thing one had thought impossible for Germany.

In the beginning it true, the whole movement in Germany appeared to be nothing but a soldiers’ revolt, an outgrowth of the discontent of the Soldiery with the Draconic severity of their commanders, a result of their aversion to the war. Yet the Soviet system was introduced overnight; Soviets were formed overnight even in the small towns. We were thus witnessing not merely a soldiers’ mutiny brought about by discontent with the war. We were witnessing the realisation of the will of the proletariat to firmly establish the new system it had fought for so long, to set up a socialist regime in place of the old order of things.

The labour councils that had sprung up overnight were, of course, very unstable as yet. The majority socialists and the adherents of Scheidemann, much better organised then workmen managed to sneak into government, seize government posts and gain a firm footing in the Soviets. The old notion of the workmen that the new order of things could be built up by merely putting a few social-democrats in place of the former rulers and ministers, was the reason why the independents and majority socialists were represented in the government of Germany.

In the first days of the revolution the workmen’s councils proposed to the adherents of the Spartacus-Union to take part in the government, and comrade Liebknecht was offered a seat in the ministry. Liebknecht declared he would go into the cabinet for three days only, in order to help the conclusion of the armistice. The majority-socialists not agreeing to this, comrade Liebknecht, and with him the other members of the Spartacus-Union, refused to participate in the government; We believed the moment had not yet come for Germany: to replace the old capitalistic state by a new social system, and we knew it would not do to merely drive away few lackeys of royalty. The chief thing was to destroy the old state machine and construct our own mechanism of power. The main thing was to show and teach the working masses, that in the first place a system of soviets had to be built up, i.e. that first of all the proletariat had to take over dictatorship. A little later measures of the government were to prove that our comrades had been quite right in not entering the cabinet. All the first decrees of government were aimed at depriving the workmen’s councils of executive power.

Haase, Dittmann, Barth and others were of the government too. Both governmental opinions had joined in issuing the first decree. Only a few days passed and they tame into collision with the Central Council. The government placed itself above the system of soviets. The officers that had been removed had their commissions returned and received their old command back again. The powers that were thought it premature to introduce socialism and proposed to postpone it for some later time. The demands of the workmen were refused, because–so they said–it was impossible to change the existing state mechanism, because the enemy was at the gates, because the Allies would not permit any changes whatsoever.

But when the protest of the proletariat against these doings became ever stronger, when the workmen would not consent to tread the old paths, the government showed its true face.

It is characteristic of German conditions that the very third day after the outbreak of the revolution the conservative press organs declared that the revolution simply did exist and could not be so easily explained away. The chief thing was–so they contended–for the government to take care that democracy should really be carried through in Germany, that democracy should be realised in practice. What they meant was a democracy of the bourgeoisie, the calling of a National Assembly. The Spartacus Union immediately pointed out that there was to be no such thing, that we needed dictatorship of the proletariat, that had created its own mechanism of organisation the soviet system, and as it was the proletariat that had achieved the revolution in Germany, it ought to be the only class called upon to build up the new state. We demanded relentless class-struggle, until total annihilation of the capitalist system. But this was not to the taste of Messrs. Scheidemann and Ebert. They declared themselves in favour of a National Assembly. Preparations for the elections were made with incredible speed. This gave the workmen their cue. The whole nation split into two groups. The representatives of capital, supporting the National Assembly stood on the one side, the Spartacus-Union with their demand for a soviet system and the dictatorship of the proletariat on the other. Such was the parole all through the contests that you know about.

Our comrades, adherents of the Spartacus-Union, had formerly been organized in the Independent Social Democrat Party. At the beginning of the war only one social democratic party existed in Germany that was being exalted to the very skies in the rest of Europe. The fact of the social-democrats and their leaders having gone over to nationalism at the outbreak of the war and fighting side by side with the bourgeoisie made it impossible for the members of the Spartacus-Union to remain in that organisation any longer. There was yet another fraction that did not agree to voting the war credits this was the fraction of Haase and Ledebour. But with regard to other questions of home defence they were at one with Scheidemann and Ebert. After showing open opposition they were ejected from the party and proceeded to form the Independent Social Democratic Party.

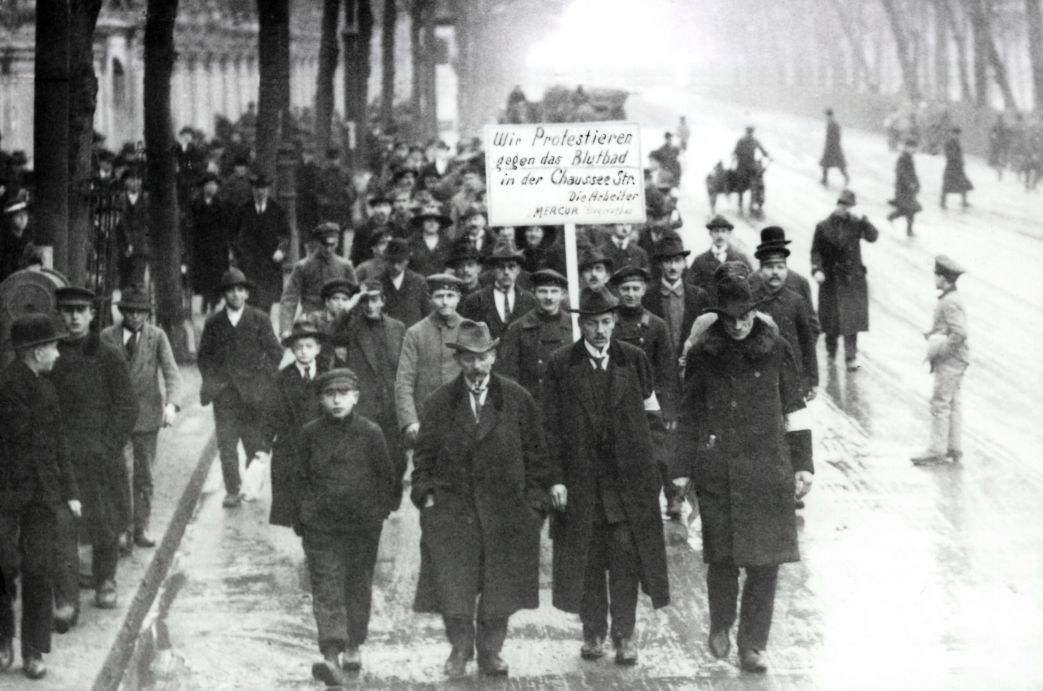

The friends of the Spartacus-Union had no possibility of working and developing their activity. The Spartacists were either thrown into prison or sent to the trenches. Only a few of them could continue work in so far as they happened to be at liberty. When the Independent Social Democratic Party was formed at Gotha we were ready to join it, but divergencies, even irreconcilable ones existed at the very outset. After the outbreak of the revolution the Independents entered the government, declared themselves in favour of bourgeois democracy and endeavoured to strangle the soviet system. Thus we could no longer work with them. On January 3rd 1919, at the conference of the Spartacus-Union in Berlin, we inaugurated the Communist Party of Germany. As soon as our party had come into being the government, under the leadership of Ebert-Scheidemann, began a relentless war against the communists. All the old methods of oppression that had formerly been practiced by the old regime were now ruthlessly applied by the new government in order to crush the Communist Party. The workmen revolted against such policy; the proletariat took recourse to strikes to prove that it would not let itself be oppressed by the old methods. At this the representatives of Ebert and Scheideman declared merciless war upon the proletariat and first ad maxim-guns and cannons, wheeled out into the streets of Berlin against the working masses. On December 6th 1818 maxim-guns and cannons fired on peacefully demonstrating workmen in the streets of Berlin, and a large number of our best comrades were killed or severely wounded. It is characteristic that persecution was most relentless against soldier-members of the communist party.

What about the German army of to-day? Having spent four years in the war and on the 9th of November overthrown the old regime by revolt the soldiers no longer wish to continue the old game. The old regiments have been dissolved. After the outbreak of the revolution they simply cut and ran without caring whether it pleased Scheidemann or not.

The military units in Germany were dissolved with in a few days after the revolution. Whole districts whose leaders belonged to the communist party carried through demobilisation at their own risk. The Brunswick Republic announced demobilisation for the 23rd of December. The Government Imperial protested, but the soldiers had already been dismissed. Moreover, it had but little sense for the government to keep back the old soldiers, for they could no longer be of any use for its aims. The old front regiments refused to fight the external enemy. Armistice or no armistice, they simply ran away, as fast as their legs could carry them. I have to say that Russia took active part in the crumbling up of our army. The prisoners of war arrived from Russia. Wherever they appeared it did not take long for all desire for war to vanish.

Some regiments at the fronts could not be reached by propaganda and continued to remain under the command of their officers, but they very soon ceased to be fit for action.

General Legius, the military commander of Berlin, declared in the beginning of January that 6 days presence in Berlin would suffice for the complete demoralisation of his troops at present still in kept hands by their officers. It was only owing to forces returning from the fronts where agitation had not yet penetrated gnat weapons were made use of against the workmen in the streets of Berlin. Thus it was on December 6th 1918 that the troops just returned from Finland, by order of the government, shot down soldiers coming from a meeting or the red soldier’s union. When a few days later the sailors forming the foundation and chief support of the revolution (mostly workmen that before too had been party-members) refused to leave Berlin by order of the government, the latter detailed a regiment from the battle-front against them and the sailors were pelted with hand grenades The cabinet members Haase, Barth and Dittman declared that they were not present at the sitting were it was decided to fire on the workmen, and the independents withdrew from government. They wore thrust out, and great was their lament at it.

The Spartacus group could no long work with them. With such people all work was illusory. The formation of a separate Communist Party was imperative, the more so as within the existing party splits were becoming more and more numerous. The majority party works harmoniously, but within the Independent Party something is rotten. Each leader represents a separate point of view, each of them urges the formation of a different party. In particular Ledebour and Däumig coveted the idea of founding a universal German party. Had this actually been done another Independent Social Democratic Party would have arisen, leaning neither to the right nor to theft, failing to advocate the cause of the extreme radicals, the Spartacus-Union and the dictatorship of the proletariat. This prompted us to immediately separate ourselves from these men and thus to counteract the formation of now hybrid party.

The task of the communist union was not only to found a new party but, first and foremost, to educate the masses, to prepare them for the introduction of the socialist order of things where each single man’s work will be of account. Every now and then the idea takes hold of the workmen that all they have to do is to replace some cabinet ministers by social democrats. It was our task to point out that the struggle against the bourgeoisie could only be carried on by means of mass-action. From the very outset it was clear to us that the revolution of November was nothing but a weak attempt at destroying the old regime, that the real revolution in Germany was yet to come.

It became evident in the course of a few weeks that the reconstruction of society on a new basis would still demand bloody fights, that civil war would flare up with a passion until now unknown to history. The masses have to be shown that their only salvation lies in the soviet system. All our agitation is directed towards making this clear to the workmen, towards inducing them to form their soviets.

How about these soviets? At first councils were formed everywhere. In works and workshops the workers elected councils with the aim of improving their conditions of work within their own establishments. For us, the import of these councils lies in their having ousted the influential German trade-unions which were at one with the yellow socialists, which prohibited strikes, opposed every open movement of the workers and attacked them from behind on every possible occasion. Since the 9th of November the trade-unions have ceased to play any role whatsoever. Since the 9th of November all economic movement has been carried on without, nay, against the trade-unions that had not once succeeded in pushing though the economic demands of the working men. Only recently did the shop-assistants’ union begin an open movement, the reason being that members of the communist party were among its leaders.

What are the prospects of the future struggle in Germany? If one is to judge by the numerical results of the elections for the National Assembly the majority socialists in Germany have the support of the overwhelming mass of the population. The Scheidemans obtained 11 million votes, the independent socialists 2 millions. But closer investigation of the movement shows that the workmen do not at all stand in such serried ranks behind the government as the latter professes they do. On the contrary, it appears that whenever the workers endeavour to gain their own ends independently and spite of the government they follow the cry of the communists. In Rhineland-Westphalia there is a widespread movement among the miners A central council was elected and entrusted with the control of the coal mines. It was not only the workmen who took part in the socialisation of the enterprises: the staff of officials declared themselves ready to carry through socialisation independently of the former owners and to join the miners in managing the works without sabotage. Of course, it is impossible to proceed to socialise a single branch of industry in a state, but! it is symptomatic that the workmen understand the only way for abolishing the old economic order to be the socialisation of the works, in fact, of economic life as a whole. The prospects for the future struggle are favourable because the economic development in Germany shows a rapidly descending curve.

It is less favourable that the government deals sharply with the workmen, but the latter are not easily to be intimidated. Wherever complications arose in Germany the soldiers declared: “We will not fight against the workmen”. But military forces that keep neutral are of no use to the government. The latter therefore proceeded to organise white guards out of volunteer regiments, after the Russian pattern. New regiments were formed to defend the Eastern frontier, the pretext was to keep down the Polish insurgents, those Poles that were oppressed by the dictatorship of the bourgeoisie and that to-day are maltreated exactly as before. On the other hand the military forces were made use of to beat back the onset of bolshevik red guards. In Germany the red guards were pictured as a gang of murdering and pillaging robbers. Active propaganda is being carried on by the government in order to win soldiers for the struggle against the bolsheviks.

These soldiers were also made use of to fight the workmen in the streets of Berlin and to crush the working men in their struggle. The first movement arose in Berlin in January 1919. The government had dismissed the prefect of the police and put a majority man in his place whose treachery had formerly won him the hatred of the working men. Thus the danger arose for the proletariat that the new prefect would proceed against them with the most brutal measures. Without waiting for a signal or instructions from the party, least of all for those of the Spartacus-Union, the workmen on January 19th occupied several printing-offices, in the first place the office of the “Vorwärts” which paper had long been an eyesore to them. After several days of struggle and occupation the majority men under the leadership bf the government sent out the first white guards to restore order in Berlin. The atrocious and brutal way in which they proceeded is evidenced by the fact that the first parlementaires issuing from the “Vorwärts” building with the flag of truce were simply flogged to death by the soldiers. After having crushed the movement, the white guards proceeded to arrest and imprison all those who openly adhered to the Spartacus-Union. Thus did our best leaders, Karl Liebknecht and Rosa Luxemburg fall into the hands of the butchers, who murdered them in the street. All the yarns about the attempted flight of Liebknecht and of the dragging away of comrade Luxemburg by the workmen is rank fraud. We are already in possession of evidence proving that Liebknecht was beaten over the head, with the butt-ends of rifles by soldiers of the white guard, was carried away in a motor-car severely wounded and thereupon shot dead. As to Rosa Luxemburg, she was killed by two blows of the butt and her corpse dragged away. The murderers and officers are known, the evidence has been published, but the murderers still walk the streets in liberty. The government never thinks of proceeding against them.

The fate of Liebknecht and Luxemburg has been shared by many other Spartacists. They were killed by fanatic soldiers and officers and their bodies thrust into the earth without much ado. Our Russian comrade Karl Radek was arrested, loaded with heavy iron chains and thrown into a damp and cold cellar, a cell, formerly the place of confinement for murderers. So you see that terror in Berlin is at its height. The struggle of the proletariat against the bourgeoisie is no longer carried on by means of leaflets and pamphlets. To-day the proletariat fights with powder and shot. The panic-stricken bourgeoisie has no other course but to keep the proletariat down by force. It has no others means at Its disposal.

The economic conditions of Germany are hopeless. Works are being closed by the dozen; by means of economic movements and strikes the workmen have won for themselves wages which make the enterprises no longer appear a paying business to the capitalist. So the simply closes shop, because it does not yield a surplus big enough for him. On the other hand the reluctance of the workmen to work is steadily growing. It is not to be wondered at that to-day, when they might have the business in their own hands, the workmen no longer want to fill the pockets of the capitalists. Their aversion is becoming greater day by day. Raw materials are scarce and wherever they are to be got at all they are being smuggled from hand to hand. That is why the capitalists close their enterprises. When I left Berlin the number of the unemployed was 200,000. The economic collapse of Germany is approaching fast.

Communication in Germany is bad. I was told at home; “If you go to Russia you will witness things!” Comrades, as compared to Germany, I travelled from the frontier, to Moscow luxuriously. The English and French have taken our best locomotives. The way from Berlin to Leipzig that formerly used to take two hours now frequently lasts 9 to 10 hours. Where express-trains used to run every hour, there are only one or two slow trains a day now. It is evident that the former method of management cannot be continued.

The food question is becoming more and more complicated. The prices for foodstuffs are continually rising, or else they are not to be obtained at all. The rations are insufficient for keeping alive and recourse has to be taken to smuggling and illegal food trading. The workmen are not in a position to purchase the necessary food-stuffs. As a direct result riots take place everywhere. The white guards are only waiting for the moment to advance against the proletariat. Thus armed collisions are unavoidable.

All this and the peace with the Allies in particular will show that the proletariat carries on its struggle in the firm hope of a successful end. The government puts the workmen off from one day to the next saying: we must not do anything; peace with the Allies is a matter of a few days. But the working masses will no longer be deceived by such lame excuses. For months we have been told that we must fight against Russia in order to win favour in the eyes of the Entente. But so far we have seen no signs of their favour, nor shall we ever do so. The few tins of condensed milk have been offered us at a price that capitalists may be able to pay, but not workmen. The Scheidemannists who four years ago sanctioned and supported the policy of war against the Allied countries, are now crawling on their bellies before the Allies and whining and praying for mercy. They are afraid of the peace. The German government, the Scheidemannists and their set have shown the Allies how peace with a vanquished enemy is made: England and France can point to Brest-Litovsk and say “you have taught us how to make peace”; and if the conditions of peace will be heavy it is because the representatives of the Entente, Wilson, Clémenceau and Co. are but the head clerks of their respective capitalistic states and regard the conclusion of peace as a business deal that is to be made the most of. Not by the government’s creeping on its belly and whining is anything to be got out of the Allies, but by the proletariat continuing its revolution with energy and passion. The confidence of England and France has to be won and the struggle for the world-revolution carried on in union with these countries.

This is the opinion of the Communist Party, and by our propaganda we will succeed in winning that part of the German proletariat for our ideas which has not yet joined us. I believe I am not too optimistic id I say that the Communist Party of Germany, as of Russia, continues its struggle in the hope that the time is not too far off when the German proletariat will succeed to bring its revolution to a glorious end: when proletarian dictatorship will be established in the teeth of all the National Assemblies of the world, in the teeth of all Scheidemann and bourgeois nationalism. For this struggle it is imperative that the proletarians of Germany take the field in close union with the proletariat of other countries. It is because I am convinced of this that I have gladly accepted your invitation, trusting that very shortly wo shall fight side by side with the proletariat of all other countries, especially that of England and France, for the realisation of the revolutionary aims in Germany.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n02-jun-1919-CI-grn-goog-r2.pdf