That place where sex and capitalism meet; an excellent look at the social economy of the burlesque show.

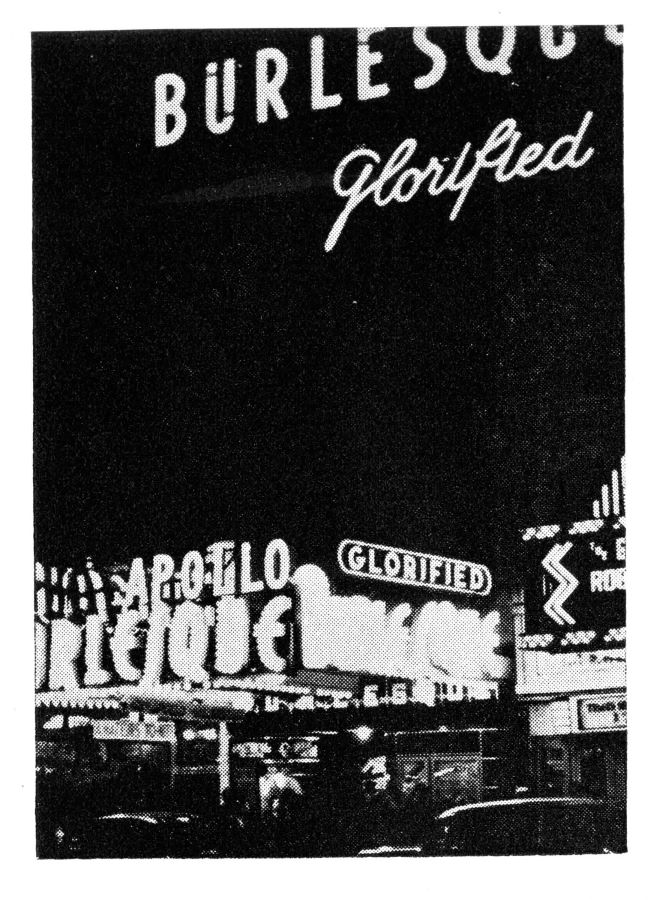

‘Burlesque’ by Philip Sterling from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 3 No. 6. June, 1936.

The burlesque stage, offering vicarious sex experience at reasonable box office prices, is almost totally divorced from reality despite its bawdy humor and bare buttocks, and therefore has little justification as an art form. Nevertheless there is an important reason for its revaluation.

“Burlycue” has remained essentially unchanged since the beginning of the century, but the people who work in it, the comics, the strip women and the chorus kids have moved forward. They have learned that there are facts of life other than sex. The sum total of their learning is contained in their recent discovery that a strong union is better than the unsecured pledge of an employer. They have found a new collective consciousness and are developing a new mode of professional life. That’s what makes it necessary to draw a line between the bad of the burlesque stage and the good of the burlesque actor.

Burlesque, like other popular entertainment forms, has been degraded from a once virile and lusty instrument of folk expression to a hollow, tinsel-draped shell, retaining only those features which are best suited to commercial exploitation.

The development of American burlesque into an undisguised sex display stems from the long-skirted, petticoat-wrapped morals of the late Victorian era when sex was a dirty word. The gay, light-hearted stage extravaganzas of the day were adjudged naughty because dancers and actresses flitted about the stage with unladylike verve leading to the evil of exposed legs, garters and/or underpants. The Black Crook, most notable of the late Nineteenth Century’s giddy stage vehicles, was good, clean fun, but Victorian society called it naughty. Ambitious showmen exploited its reputation and produced more daring pieces. Slowly the elements of simple entertainment in burlesque gave way to the present-day exploitation of sex. Its excuse for living is still good, clean fun. It’s never clean and it’s seldom good fun.

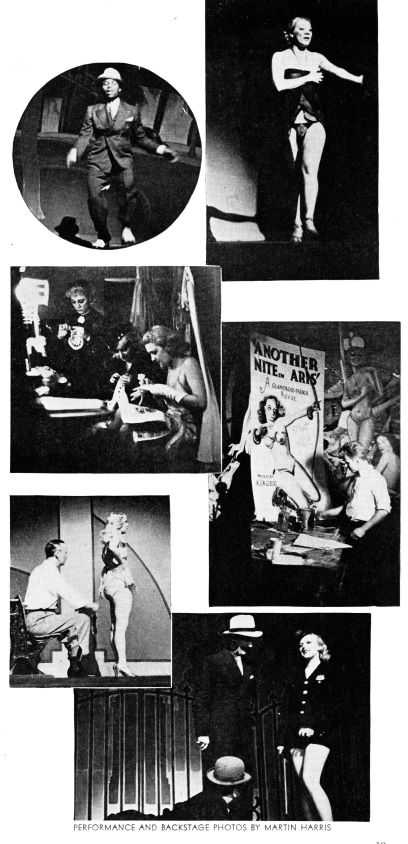

The structure of a burlesque show is simple. Every show opens with a chorus number. Then follows a comedy bit involving two or three comics. The mouldy senility of the comic bits is seldom relieved by any freshness of treatment.

The comic scenes are divided into two main types. One deals with the gullibility of the self-styled “wise guy” who inevitably meets disaster in his attempt to flim-flam someone else. The other is an elaborate piece of dialogue built around one or a series of sexy double meanings. Only occasionally does one find vestigial remnants of true burlesque.

There may be a scene in which the comic, appropriately garbed, is being instructed in the art of bull-fighting. The dialogue goes something like this:

Straight Man: “When the bull comes out you wave your cape.”

Comic: “Then what do I do?”

Straight Man: “You gotta be careful because the bull’s liable to hurt your pickador.” (At this point the comic’s reply and his gestures indicate that he believes a pickador to be some part of his anatomy.)

Straight Man:

“When you kill the bull, you walk over to the side of the arena, you bow, and you look up at the queen’s box.”

Comic (looking coy and roguish): “Do I have to wait till I kill the bull?” Straight Man: “Sure. It ought to be easy for you. You’ve been shooting the bull for years.”

From this point the scene may go on and end with a punch-line which has no connection with bull-fighting nor with anything else that went before.

Or there may be a scene in a haunted house in which the comic pretends to be dreadfully frightened and the straight dreadfully frightened and the straight man fearlessly announces his determination to lay the ghost. Whereupon there will be much ado because the comic, in his simulated fright confuses “ghost” with “goat.”

After the comedy blackout, which burlesque is credited with having originated, comes the strip number, which today has become the chief attraction. The stripper sings a popular tune which is usually neither new nor tuneful. There was a time when most strip women couldn’t do anything but strip. Today, however, one finds an increasing number who have some slight accomplishments in the way of song or dance. She sings her first chorus fully clothed, although she is toying with the pins that secure her specially designed costume. On the second chorus the lights change and as she sings she begins to divest herself of either the bottom or top part of her gown. Half undressed she struts, dances or skips, according to her degree of accomplishment, across the stage, timing the removal of the rest of her costume with her exit and the last bars of the music. On her third appearance she may have part of her gown thrown loosely about her but before she makes her final exit she is again totally disrobed save for a small beaded “G-string.”

During the depression, when burlesque operators, like other showmen, would have displayed their grandmothers in pink tights to bolster falling box-office receipts, nudity became desperately nude. As a result the flesh displays have reached almost their extreme limit.

The strip act is followed by a chorus number, the dancing routines and costumes of which are generally simplified from those of a high-priced revue. The specialty number follows. This may be a tap dancer, a singer, a quartette. In the specialty number the chorus may again be brought into play with banal but revealing costumes. Multiply this sequence by four or five and you have a burlesque show.

One of the most revealing phenomena is the spieling concessionaire who holds forth between performances. His technique is eloquent of the low esteem in which burlesque operators hold the intelligence of their patrons. After his routine announcements of chocolates, cigars, cigarettes, orangeade, always couched in superlatives, he launches into the following rapid-fire peroration:

“Now ladies and gentlemen: I want to call to your attention today a special imported French novelty which we are prepared to pass out to each and every patron of this show. I know you’re all broad-minded and you enjoy a good laugh, and I’ve got something here that you wouldn’t part with for fifty cents or a dollar once you get it. Now I am not asking fifty cents or a dollar. I’m not even going to sell it because it’s against the law. But nobody can stop me from giving it away as a little souvenir. I have here an imported French booklet showing a group of French models and as you turn the pages you will get a good idea from the pictures of what certain people do under certain conditions. It leaves nothing to your imagination. I am not selling these but with every ten-cent bar of this famous brand of chocolate the boys will give you one of these booklets as they pass up the aisle.”

Who goes to these shows? Manual and white-collar workers and various strata of the lower middle class the same people who go to the movies. Without question the major part of these audiences see through the banality, and hollow merriment of the shows.

If the patrons of burlesque continue to support it despite its obvious sham it is not because of any inherent viciousness. Joseph Wood Krutch’s explanation, though mildly phrased, is apt:

“The dogged patience with which hundreds of men sit through insipidity after insipidity is proof that this queer society of ours shuts out a considerable portion of its members from adequate contact with experiences which human nature cannot be kept from craving.”

If burlesque is so bad, what about the people who work in it? Who but individuals of loose morals and low intellectual caliber would permit themselves to be agencies of such shabbily disguised lewdness and salaciousness? That’s like asking who but a person intent on suicide would be a steeple-jack or a sand-hog. The fact is that most people have little choice of employment. Occupations are largely determined by momentary necessity and by the accidents arising therefrom.

Burlesque chorus girls and show girls get $25.50 a week in stock companies and three dollars more on the road. Principals, strip women and comics, get as low as $40 but their pay is scaled upward according to their personal reputation as drawing cards. They average close to $60 a week. In New York City the working week averages about 70 hours. That means four shows a day, a midnight performance on Saturday nights and about three rehearsals a week which last from 1 A.M. to almost any time.

Until several months ago, when the Burlesque Artists Association led its first successful strike, the working week was from 82 to 90 hours. Girls got from $15 to $21 a week and principals were kept close to the $40 minimum. In addition, the chorus captain, whose loyalty to the employer was purchased by a few dollars. extra per week and by greater security of tenure, had powers of life and death over the jobs of the girls in the line. She could impose fines, she could recommend dismissals and she could work her chorus as long and as cruelly as she liked.

For a long time there was no such thing as a notice of closing or dismissal. Today closing notices are required by the union and either notice or pay is given. Transportation is provided by the operator for persons dismissed from the cast while shows are on the road.

During the depths of the depression burlesque operators, paying as little as $15 a week to chorus girls, followed at practice unparalleled in the annals of crooked showmanship. Principals and chorus members alike, on opening their pay envelopes would find only part of their salary. Substituted for the balance would be a warmly worded note thanking the members of the cast for their cooperation with the management “in these trying times.”

The boast of burlesque impressarios that their medium is a smelter from which the true gold of theatre talent emerges free of its base ores is no longer valid. In the days before burlesque slipped from two-a-day to its present continuous policy it did produce a long list of stars: Al Jolson, Bert Lahr, Will Rogers, Weber and Fields, Eddie Cantor, Clark and McCullogh, Fred Stone, Fannie Brice, James Barton, Willie and Eugene Howard and Sophie Tucker. Unless there is a burlesque renaissance, those days are gone forever.

Whether or no burlesque as it stands today deserves an opportunity for a renaissance is quite another question. Operators talk long and fondly of producing “script shows,” with lighting, costuming and music which will rival the expensive reviews. No doubt such an effort has commercial possibilities, but experience has proved in every branch of the American stage that commercial possibilities are not often consistent with the best interests of the theatre. The ideal route to salvation for burlesque would be the liquidation of the form in which it exists and the development of a stage devoted to light musical travesties of the current dance, drama, musical and entertainment world with frequent incursions in the field of political and social comment.

As matters stand such a suggestion is utopian. We may as well reconcile ourselves to the fact that as long as “this queer society of ours shuts out a considerable portion of its members” from experiences which human nature will not be denied, vulgarly flaunted nudity and smut at reasonable prices will be offered from the stage in one form or another.

Meanwhile lovers of the theatre should be actively interested in the welfare of the burlesque performers. Actors in other fields must make a conscious effort through their professional organizations to end the isolation and ostracism forced on members of the burlesque stage by traditions of false individualism.

The entire theatre world will gain by assisting the burlesque artists in their efforts to preserve their integrity as wage-earners on stages where an actor is less an actor than a promoter’s puppet.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n06-jun-1936-New-Theatre.pdf