A chapter on ‘social instincts’ from Kautsky’s larger work on materialism.

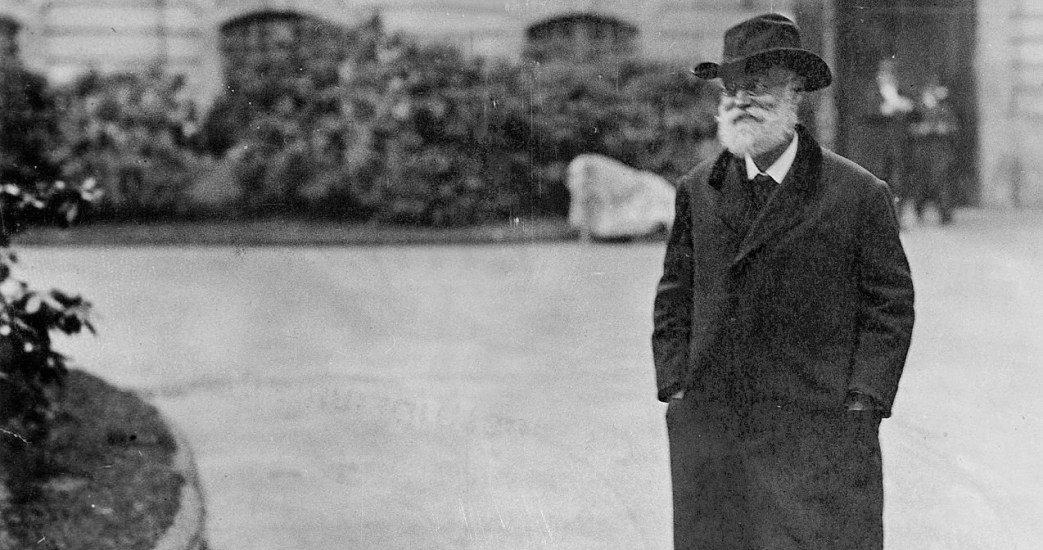

‘The Influence of the Social Instincts: Internationalism and Class Division’ by Karl Kautsky from Ethics and the Materialist Conception of History. Charles H. Kerr Publishers, Chicago. 1906.

a. Internationalism

Far more than the degree of strength does the sphere in which the social instincts are effective alter itself. The traditional Ethics looked on the moral law as the force which regulates the relations of man to man. Since it starts with the individual and not with the society it overlooks the fact certainly that the moral law does not regulate the intercourse of men with every other man, but simply with men of the same society. That it only holds good for these will be comprehensible when we recollect the origin of the social instincts. They are a means to increase the social cohesion, to add to the strength of society. The animal has social instincts only for members of his own herd, the other herds are more or less indifferent to him. Among social beasts of prey we find direct hostility to the members of other herds. Thus the pariah dogs of Constantinople in every street look very carefully out that no other dog comes into the district. It would be at once chased away or even torn to pieces.

In a similar relation do the human herds come, so soon as hunting and war rise in their midst. One of the most important forms of the struggle for existence is now for them the struggle of the herd against other herds of the same kind. The man who is not a member of the same society becomes a direct enemy. The social impulses do not only not hold good for him but directly against him. The stronger they are, the better does the tribe hold together against the common foe, so much the more energetically do they fight the latter. The social virtues, mutual help, self sacrifice, love of truth, etc., apply only to fellow tribesmen not for the members of another social organization.

It excited much resentment against me when I started these facts in the Neue Zeit and my statement was interpreted as if I had attempted to establish a special social democratic principle in opposition to the principles of the eternal moral law, which demands unconditional truthfulness to all men. In reality I have only spoken out that which has from the time when our forefathers became men lived as the moral law with- in our breasts, viz., that over against the enemy the social virtues are not required. There is no need, however, on that account that anybody should be especially indignant with the social democracy because there is no party which interprets the idea of society more widely than they, the party of internationalism, which draws all nations, all races into the sphere of their solidarity.

If the moral law applies only to members of our own society, its extent is still by no means fixed once for all. It grows far more in the same degree in which the division of labor progresses, the productivity of human labor grows as well as the means of human intercourse improve. The number of people increase whom a certain territory can support, who are bound to work in a certain territory for one another and with one another and who thus are socially tied together. But also the number of territories increase whose inhabitants live in connection with each other in order to work for each other and form a social union. Finally the range of the territories extends itself which enter into fixed social dependence on each other and form a permanent social organization with a common language, common customs, common laws.

After the death of Alexander of Macedonia the peoples of the Eastern Mediterranean had formed already an international circle with an international language, – Greek. After the rise of the Romans all the lands round the Mediterranean became a still wider international circle, in which the national distinctions disappeared, and looked upon themselves as the representatives of humanity.

The new religion of the circle which took the place of the old national religions, was from the very beginning a world religion with one God, who embraced the entire world, and before whom all men were equal. This religion applied itself to all mankind, and declared them ail to be children of one God, all brothers.

But in fact the moral law held good even here only for the members of their own circle of culture for “Christians”, for “believers”. And the centre of gravity in Christianity came ever more and more towards the north and west during the migration of the peoples. In the South and East there formed itself a new circle of culture with its one morality, that of Islam, which forced its way forward in Asia and Africa, as the Christian in Europe.

Now, however, this last expanded itself thanks to capitalism, ever and more to a universal civilization, which embraced Buddhists, Moslems, Parsees, Brahmans, as well as Christians, who more and more ceased to be real Christians.

Thus there formed itself a foundation for the final realization of that moral conception already expressed by Christianity, though very prematurely, so that it could not be fulfilled, and which thus remained for the majority of Christians a simple phrase, the conception of the equality of men, a view that the social instincts, the moral virtues are to be exercised towards all men in equal fashion. This foundation of a general human morality is being formed not by a moral improvement of humanity, whatever we are to understand by that, but by the development of the productive forces of man, by the extension of the social division of human labor, the perfection of the means of intercourse. This new morality is, however, even today far from being a morality of all men even in the economically progressive countries. It is in essence even today the moral of the class conscious proletariat, that part of the proletariat which in its feeling and thinking has emancipated itself from the rest of the people and has formed its own morality in opposition to the Bourgeoisie.

Certainly it is capital which creates the material foundation for a general human morality, but it only creates the foundation by treading this morality continually under its feet. The capitalist nations of the circle of European Society spread this by widening their sphere of exploitation which is only possible by means of force. They thus create the foundations of a future universal solidarity of the nations by a universal exploitation of all nations, and those of the drawing in of all colonial lands into the circle of European culture by the oppression of all colonial lands with the worst and most forcible weapons of a most brutal barbarism.

The proletariat alone have no share in the capitalist exploitation; they fight it and must fight it and they will on the foundation laid down by capital of world intercourses and world commerce create a form of society, in which the equality of man before the moral law will become – instead of a mere pious wish – reality.

b. The Class Division.

But if the economic development thus tends to make wider the circle of society within which the social impulses and virtues have effect till it embraces finally the whole of humanity, it at the same time creates not only private interests within society which are capable of considerably diminishing the effect of these social impulses, for the time, but also special classes of society, which while within their own narrow circle greatly intensifying the strength of the social instincts and virtues, at the same time, however, can materially injure their value for the other members of the entire society or at least for the opposing sections or classes.

The formation of classes is also a product of the division of labor. Even the animal society is no homogeneous formation. In its bosom there are already various groups, which have a different importance in and for the community. Yet the group-formation still rests on the natural distinctions. There is in the first place that of sex, then of age. Within each sex, we find the groups of the children, the youths of both sexes, the adults, and finally the aged. The discovery of the tool has at first the effect of emphasizing still more the separation of certain of these Groups. Thus hunting and war fall to the men, who are more easily able to get about than the women, who are continually burdened with children. That and not any inferior power of self defence probably it was which made hunting and fighting a monopoly of man. Wherever in history and fable we come across female huntresses and warriors, they are always the unmarried. Women do not lack in strength, endurance or courage, but maternity is not easily to be reconciled with the insecure life of the hunter and warrior. As, however, motherhood drives the woman rather to continually stay in one place those duties fall to her which require a settled life, the planting of field fruits, the maintenance of the family hearth.

According to the importance which now hunting and war, on the other side agriculture and domestic life attain for society, and according to the share which each of the two sexes has in these employments, changes the importance and relative respect paid to the man and woman in the social life. But even the importance of the various ages depends on the method of production. Does hunting preponderate, which renders the sources of food very precarious, and from time to time necessitates great migrations, the old people become easily a burden to the society. They are often killed, sometimes even eaten. It is different when the people are settled; the breeding of animals and agriculture produce a more plentiful return. Now the old people can remain at home and there is no lack of food for them. Now is, however, at the same time a great sum of experiences and knowledge stored up, whose guardians, so long as writing was not discovered or become common property of the peoples are the old folk. They are the handers down of what might be called the beginning of science. Thus they are not now looked on as a painful burden, but honored as the bearers of a higher wisdom. Writing and printing deprive the old people of the privilege to incorporate in their persons the sum of all experiences and traditions of the society. The continual revolutionizing of all experience, which is the characteristic feature of the modern system of production, makes the old traditions even hostile to the new. The latter counts without any further ado as the better, the old as antiquated and hence bad. The old only receives sympathy, it enjoys no longer any prestige. There is now no higher praise for an old man than that he is still young and still capable of taking in new ideas.

As the respect paid to the sexes, so does the respect paid to the various ages alter in society with the various methods of production.

The progressive division of labor brings further distinctions within each sex, most among the men. The woman is in the first place more and more tied to the household whose range diminishes, instead of growing, as ever more branches of production break away from it, become independent and a domain of the men. Technical progress, division of labor, the separation into trades was limited till last century almost exclusively to men; the household and the woman have been only slightly affected by these changes.

The more this separation into different professions advances, the more complicated does the social organism become, whose organs they form. The nature and method of their co-operation in the fundamental social process, with other words the method of production, has nothing of chance about it. It is quite independent of the will of the individuals, and is necessarily determined by the given material conditions. Among these the technical factor is again the most Important, and that phase whose development affects the method of production. But it is not the only one.

Let us take an example. The materialist conception of history has been often understood as if certain technical conditions of itself meant a certain method of production, nay, even certain social and political forms. As that, however, is not exact, since we find the same tools in various states of society, consequently the materialist conception of history is false and the social relations are not determined by the technical conditions. The objection is right, but it does not hit the materialist conception of history, but its caricature, by a confusion of technical conditions and method of production.

It has been said for instance, the plough forms the foundation of the peasant economy. But manifold are the social circumstances in which this appears!

Certainly! But let us look a little more closely. What brings about the deviations of the various forms of society which arise on the peasant foundations.

Let us take for example a peasantry, which lives on the banks of a great tropical or subtropical river, which periodically floods its banks, bringing either decay or fruitfulness for the soil. Water dams, etc., will be required to keep the water back here and to guide it there. The single village is not able to carry out such works by itself. A number of them must co-operate, and supply laborers, common officials must be appointed, with a commission to set the labor going for making and maintaining the works. The bigger the undertaking, the more villages must take a part, the greater the number of the forced laborers, the greater the special knowledge required to conduct such works, so much the greater the power, and knowledge of the leading officials compared with the rest of the population. Thus there grows on the foundation of a peasant economy a priest or official class as in the river plains of the Nile, the Euphrates or the Whang-Ho.

We find another species of development where a flourishing peasant economy has settled in fruitful, accessible lands in the neighborhood of robbers, nomadic tribes. The necessity of guarding themselves against these nomads forces the peasants to form a force of guards, which can be done in various manners. Either a part of the peasant applies itself to the trade of arms, and separates itself from the others who yield them services in return, or the robber neighbors are induced by payment of a tribute to keep the peace and to protect their new proteges from other robbers, or finally the robbers conquer the land and remain as lords over the peasantry, on whom they lay a tribute, for which, however they provide a protective force. The result is always the same: the rise of a new feudal nobility which rules and exploits the peasants.

Occasionally the first and second methods of development unite, then we have beside a priest and official class a warrior caste.

Again quite differently does the peasantry develop on a sea with good harbors, which favor sea voyages and bring them closer to other coasts with well to do populations. By the side of agriculture, fishery arises, fishery which soon passes over into sea-piracy and sea commerce. At a particularly suitable spot for a harbor is gathered together plunder and merchants’ goods and there is formed a town of rich merchants. Here the peasant has a market for his goods, there arise for him money receipts, but also the expenditure of money, money obligations, debts. Soon he is the debtor of the town money proprietor.

Sea piracy and sea commerce as well as sea wars bring, however, a plentiful supply of slaves into the country. The town money owners instead of exploiting their peasant debtors any farther, go to work to drive them from their possessions, to unite these into great plantations and to introduce slave work for peasant, without any change being required in the tools and instruments of agriculture.

Finally we see a fourth type of peasant development in inaccessible mountain regions. The soil is there poor and difficult to cultivate. By the side of the agriculture, the breeding of stock retains the preponderance; nevertheless both are not sufficient to sustain a great increase of population. At the foot of the mountains fruitful, well tilled lands tempt them. The mountain peasants will make the attempt to conquer these and exploit them, or where they meet with resistance to hire out their superfluous population as paid soldiers. Their experience in war, in combination with the poverty and inaccessibility of their land serves to guard it against foreign invaders, to whom in any case their poverty offers no great temptation. There the old peasant democracy still maintains when all around all the peasantry have long become dependent on Feudal Lords, Priests, Merchants and usurers. Occasionally a primitive democracy of that kind itself tyrannizes and explores a neighboring country which they have conquered, in marked contradiction to their own highly valued liberty. Thus the old cantons of the fatherland of William Tell exercised through their Bailiffs in Tessin in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries a rule, whose crushing weight could compare with that of the mythical Gessler.

It will be seen that very different methods of production are compatible with the peasant economy. How are these differences to be explained? The opponents of the materialist conception of history trace them back to force, or again to the difference of the ideas which take form at various periods in the various peoples.

Now it is certain that in the erection of all these methods of production force played a great part, and Marx called it the midwife of every new society. But whence comes this role of force, how does it come that one section of the people conquers with it, and the other not, and that the force produces this and not other results? To all these questions the force theory has no answer to give. And equally by the theory of ideas does it remain a mystery where the ideas come from which lead to freedom in the mountain country, to priest rule in the river valley land, to money and slave economy on the shores of the sea and in hilly undulating countries to feudal serfdom.

We have seen that these differences in the development of the same peasant system rest on differences in the natural and social surroundings in which this system is placed. According to the nature of the land, according to the description of its neighbors will the peasant system of economy be the foundation for very different social forms. These special social forms become then side by side with the natural factors, further foundations, which give a peculiar form to the development based on them. Thus the Germans found when they burst in on the Roman Empire during the migration of the peoples, the Imperial Government with its bureaucracy, the municipal system, the Christian Church as social conditions, and these, as well as they could, they incorporated into their system.

All these geographical and historical conditions have to be studied, if the particular method of production in a land at a particular time is to be understood. The knowledge of the technical conditions alone does not suffice.

It will be seen that the materialist conception of history is not such a simple formula as its critics usually conceive it to be. The examples here given show us, however, also how class differences and class antagonisms are produced by the economic development.

Differences not simply between individuals but also between individual groups within the society existed already in the animal world as we have remarked already, distinctions in the strength, the reputation, perhaps even of the material position of individuals and groups. Such distinctions are natural and will be hardly likely to disappear even in a socialist society. The discovery of tools, the division of labor, and its consequences, in short the economic development contributes still further to increase such difference or even to create new. In any case, they cannot exceed a certain narrow limit, so long as the social labor does not yield a surplus over that necessary to the maintenance of the members of the society. As long as that is not the case, no idlers can be maintained at the cost of society, none can get considerably more in social products than the other. At the same time, however, there arise at this very stage owing to the increasing enmity of the tribes to each other and the bloody method of settling their differences, as well as through the common labor and the common property so many new factors, through which the social instincts are strengthened that the small jealousies and differences arising between the families, the different degrees of age or the various callings can just as little bring a split in the community as that between individuals. Despite the beginnings of division of labor which are to be found there, human society was never more closely bound up together or more in unison than at the time of the primitive gentile co-operative society which preceded the beginning of class antagonisms.

The things, however, alter, so soon as social labor begins, in consequence of its necessary productivity, to produce a surplus. Now it becomes possible for single individuals and professions to secure for themselves permanently a greater share in the social product than the others can secure. Single individuals, only seldom temporarily and as a matter of exception will be able to achieve that for themselves alone; on the other hand it is very obvious that any class specially favored in any particular manner by the circumstances, for example such as are conferred by special knowledge or special powers of self defence, can acquire the strength to permanently appropriate the social surplus for themselves. Property in the products is narrowly bound up with property in the means of production, who possesses the latter can dispose of the former. The endeavors to monopolize the social surplus by the privileged class produce in it the desire to monopolize and take sole possession of the means of production. The forms of this monopoly can be very diverse, either common ownership of the ruling class, or caste, or private property of the individual families or individuals of this class.

In one way or another the mass of the working people becomes disinherited, degraded to slaves, serfs, wage laborers; and with the common property in the means of production and their use in common is the strongest bond torn asunder which held primitive society together.

And where the social distinctions which managed to form themselves in the bosom of primitive society kept within narrow limits, now the class distinctions which can form themselves have practically no limit. They can grow on the one side through the technical progress which increases the surplus of the product of the social labor over the amount necessary to the simple maintenance of society; on the other hand through the expansion of the community while the number of the exploiters remains the same or even decreases, so that the number of those working and producing surplus for each exploiter grows. In this way the class distinctions can enormously increase, and with them grow the social antagonisms.

In the degree in which this development advances society is more and more divided: the class struggle becomes the principal, most general and continuous form of the struggle of the individuals for life in human society; in the same degree the social instincts towards society as a whole lose strength, they become, however, so much the stronger within that class whose welfare is for the mass of the individuals always more and more identical with that of the commonweal.

But it is specially the exploited, oppressed and uprising classes in whom the class war thus strengthens the social instincts and virtues. And that because they are obliged to put their whole personality into this with much more intensity than the ruling classes, who are often in a position to leave their defence, be it with the weapons of war, be it with the weapons of the intellect, to hirelings. Besides that, however, the ruling classes are often deeply divided internally through the struggles between themselves for the social surplus and over the means of production. One of the strongest causes of that kind of division we have learnt in the battle of competition.

All these factors, which work against the social instincts, find none or little soil in the exploited classes. The smaller this soil, the less property that the struggling classes have, the more they are forced back on their own strength, the stronger do their members feel their solidarity against the ruling classes, and the stronger do their own social feelings towards their own class grow.

Charles H Kerr publishing house was responsible for some of the earliest translations and editions of Marx, Engels, and other leaders of the socialist movement in the United States. Publisher of the Socialist Party aligned International Socialist Review, the Charles H Kerr Co. was an exponent of the Party’s left wing and the most important left publisher of the pre-Communist US workers movement. It remains a left wing publisher today.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/ethicsmaterialis00kaut/ethicsmaterialis00kaut.pdf