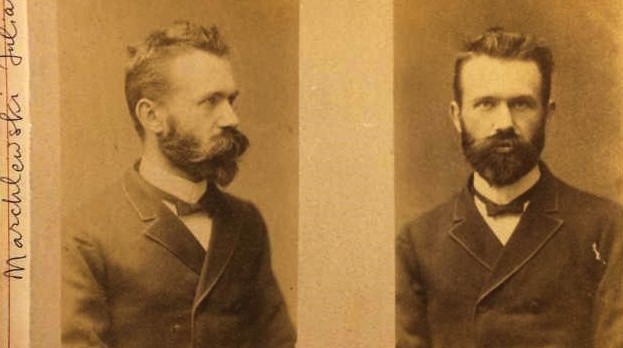

A fascinating discussion piece on European agriculture as the Comintern prepared to take up the ‘peasant question’ at the 2nd World Congress from leading Marxist Julian Marchlewski. Karski was among the closest and oldest comrade to Rosa Luxemburg and Leo Jogiches since the three formed a political bond during their 1892 exile in Zurich, where they established the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland together. Closely associated with the Polish movement, Karski was a founder and leader of the early Comintern until his death in 1925.

‘The Agrarian Question and the World Revolution’ by Julian Marchlewski (Karski) from Communist International. Vol. 1 No. 11-12. June-July, 1920.

IT is not a mere chance that the Second International never put the Agrarian Question on the program of its congresses, while the Communist International felt the necessity of approaching the question at once. The fact is that as long as the Socialist parties only talked of revolution without ever facing the immediate necessity of revolutionary acts, there was in regard to the land at the utmost only the question of propaganda among the agrarian workers and the small peasantry, and in their parliamentary work they had to do now and then only with separate agricultural reforms. But the conditions of agriculture being, as it appeared, so absolutely different for each country, it seemed to be of no use whatever to treat these questions on an international scale. Matters are quite different now in the face of revolutionary acts. We are met here from the start with the commonplace but very fundamental fact that the social division of work which had resulted in capitalist society in a total division between town and country, is of the utmost importance for the revolutionary movement. The makers of the revolution, the proletarians of the towns and industrial centres, must be fed, and their active force will be neutralized if the country is counter-revolutionary and denies them the necessary food stuffs. This is the more so in the present situation, the massacre of the nations having resulted in an unheard-of shortage of food-stuffs. Every revolutionary act depends now on what will be the attitude of the agricultural population in regard to the proletarian, the feeding of the towns being closely connected with this attitude, and all these matters have a primary importance. The Russian revolution offers in this respect a great deal of very instructive material, and these Russian experiences must be taken into consideration! But it ought to be considered on the other hand that the situation which arose in Russia cannot repeat itself in any other country. The Russian peasantry, to begin with, was in an objectively revolutionary state, although it was not subjectively aware of it, and such a revolutionary situation is a result of historic facts. Serfdom was abolished in Russia but fifty years ago, and the capitalist system had not yet asserted itself in full in agriculture. Russia remained until the revolution of 1917 the country of enormous landed property, but big capitalistic industry was carried on in quite insignificant proportion on the large estates in Great Russia. The landlords did not manage their estates themselves; they farmed out the land to the peasants and almost exclusively on short lease, the pauperized peasant not being able, in contrast to the American or English farmer, to offer any guarantees of well organized intensive agriculture. This resulted in an extremely backward form of extensive agriculture which has hardly its like in the captalistic world, and in consequence with an incredible low rate of income. Even on good soil the peasant reaped crops which were 200% lower than the crops on much inferior soil in middle and western Europe. Russia nevertheless exported great quantities of corn. It was not, however, its overproduce exceeding the home need which the empire of the czars offered for sale on the world’s market; the economic policy of the government was such as to force the peasant to sell his products while he himself suffered want and was literally starving. This situation was drawing towards a revolutionary issue: the peasant became an ally of the proletariat, which was to secure to him the possession of land and the use of the products of his toil. But the peasant, who had very radical ideas in regard to the right of property of the landlords, was nevertheless far from being revolutionary in the objective sense, and was not in the least inclined to help in the building up of a proletarian state. If matters developed according to the wishes of the peasantry, an economic system would arise on the land comprizing unlimited private property of the peasants in regard to their land particles. We see in consequence a large part of the peasantry passing into the counter revolutionary camp, and only the hard fact that the leading elements of the counter-revolution, the landlords, the bourgeoisie and the bureaucracy–the tchinovniks–were not willing to give their sanction to the “robbery of private property” brought the peasantry back to reason. The animal egotism of the peasants made them further deny foodstuffs to the towns even where there was plenty for the peasants themselves. The proletarian government had to use violence against that sort of animal egotism to save the large towns from absolute starvation. It was the more needed considering that industry, ruined by the war and the troubles of the civil war, was not able to supply products for a rational exchange of commodities between town and country. The thin population of the country, the relatively small numbered town population, and finally the fact that in Russia a very great number of the working class population is not yet quite cut off from the country but is, on the contrary, strongly tied up with it by family connections, made it possible to win time and to solve organically the conflict between town and country. In spite of the ruined transport, means were found to provision the towns, at least in a modest measure, and a large portion of the working masses sought refuge from the starving towns in the country. Matters are different in western Europe and America. The revolutionary proletariat will meet there during the period of the struggle still greater difficulties in the question of food supplies for the towns, and the relations between town and country require other solutions than those possible in Russia. This alone makes it necessary to elucidate the agrarian question in its full extent, and before all from the point of view of a revolutionary upheaval.

It is by no means the object of these lines to set up the program of the Communist International in the agrarian question, the more so that in consideration of the different conditions prevailing in the different countries there could be no general program for all countries. My only object is to take note of the different questions as they arise, and to put them under discussion.

THE STRUCTURE OF LANDED PROPERTY, AND THE CONDITIONS OF ITS CULTIVATION IN THE EUROPEAN COUNTRIES.

In order to facilitate a general view of the situation, we propose to study the agrarian conditions in the different European countries in two groups:

a) Countries where gross agriculture ranks foremost, and b) the countries with agricultural conditions determined by the land being owned and cultivated by peasants.

This will make it possible to arrive at some agreement as to the general lines of a revolutionary agrarian policy. We will have, of course, to put up with some generalizations, but this has no importance, our object being only to draw a general outline of the program which will need to be adjusted and corrected for every country separately.

The first group comprises “Central Europe” but not in the usual sense of this denomination. This is a region with peculiar agrarian conditions, where gross agriculture plays a prominent part, and this region stretches approximatively from the Dnieper in the east up to beyond the Elbe in the west and from the Baltic to the Balkans. Outside of this region in the west, south and the north of Europe we have to deal with a different agrarian system.

This “Central European” zone is by no means homogeneous in regard to the agrarian system, but in all the countries within its bounds: in Lettland, Lithuania, Poland, the Ukraine, Rumania, Hungary, Bohemia, east Germany and a part of Austria we observe the preponderance of gross agriculture. The historic reasons are everywhere the same: the comparatively recent abolition of serfdom. We see everywhere in this zone more or less apparent rudiments of an agrarian system based on the servitude of the peasants, and the conditions in this respect are certainly very different in the separate countries. But the one important fact to note is this: in this zone large landed property is of much importance, taking up in some of the countries 30 to 50% and more of the area, and on these big estates agriculture is carried on on capitalistic principles. It is the system of gross agriculture that prevails there.

The consequence is that in these countries we have to deal with a comparatively numerous stratum of unpossessing agricultural workers, that is to say of genuine proletarians. There is further in nearly all these countries a second stratum, also very largely represented–those who own particles of land property. They are not “regular peasants”: they possess too little land to live on its products and they find their subsistence chiefly in working for wages on the big estates. They are in consequence “half proletarians”.

The peasantry constitutes a very substantial part of the population in these countries. But the peasants do not represent everywhere an absolute majority if the half proletarians are to be counted apart. Although Shäffle’s words about the “anti-collectivist skull of the peasants” be true also in regard to the peasants of our “Central Europe”, the peasants are nevertheless a revolutionary element in certain respects, the conflict between the landlords (the “barons” in Lettland, the “schliachtitchs” in Poland, the Lithuania and the Ukraine, the “magnates” in Hungary, the “Junkers” in east Germany) and the peasants being a substantial factor in the political and social life of these countries. The landlord preserves in this zone, as a capitalistic enterpriser, many privileges over the peasantry, and this leads to numerous conflicts which make the peasants feel revolutionary in a certain sense.

In the countries of this “Central European” zone we have in consequence to deal with proletarian and half proletarian elements (propertyless agricultural labourers and owners of particles of land) who are certainly to be won for the revolution, and with a peasantry which is so far revolutionary as it is greatly interested in the unconditional overthrow of the political supremacy of the landlords. The only counter-revolutionary element to be taken into consideration, an element ready to side with the “Junkers” are the landed peasants but there are only few of them in nearly all these countries.

This suggests the idea of winning the proletarian, half proletarian and peasant elements by a program which simply proclaims the partition of the big landed property among the population on the land. But such a proceeding would have been reactionary in regard to the conditions of production. Contrary to all talk of the “democratic” and “revisionist” theoreticians, the economic superiority of gross agriculture over the small is beyond all doubt, particularly in this zone representing by its climatic conditions the zone of agriculture. To destroy the gross agriculture, organized everywhere within this zone on a more or less rational footing, would result in an absolute falling off of the ground rent.

And things stand after all so that a partition of the big landed property would not offer any particular profits to the peasants of this region: there is not sufficient land for that. The propertyless agricultural labourers and the owners of particles of land would have to be provided for in the first place, as they would lose their means of subsistence with the abolition of the large estates, and the area of the big landed property being hardly sufficient to provide for these two categories just the smallest necessary bit of land, there would remain simply nothing for the labouring peasants. It is also untrue that the agricultural labourers are eager to become owners under all circumstances. They know very well that the position of a more or less well-paid agricultural labourer is a more favourable one than that of a small peasant involved in debts. who works the skin off his hands on his few acres of land and is never out of troubles and want.

The labouring peasant population of this zone is, as mentioned above, as far interested in the revolution as it stands in a sharp political opposition to the owners of big estates. But this peasant population is most certainly not to be won for a Communist economic system. There is, however, no necessity of a revolutionary interference in the property conditions of the peasants. Without renouncing the Communist final aims the proletariat may after its victory leave the development of social conditions in this branch to the course of time. Nothing but experience will convince the peasantry of the advantages offered by Communistic gross agriculture.

But the proletarian revolution has to offer immediate and very substantial advantages to the peasants. The peasant is enslaved by heavy debts to financial capital. In declaring after the establishment of its dictatorship all these debts of the peasants as fully acquitted, the proletariat makes the peasants a present equal to a considerable increase of their wealth. The peasants will moreover only win with the change. The system of the councils will give them an actual autonomy satisfying all their demands of rent meliorations, improved conditions of transport, the unions etc.

This does not signify the winning of the peasants for the Communist program but only neutralize them in the decisive struggle between the proletariat and capital. This is a compromise profitable for both parties, and the Communist Party of this zone has in consequence to agree upon the following agrarian program:

In consequence of political as well as economic reasons the owners of big estates are considered as the chief enemies who are to be overthrown under any circumstances.

The landed property of these landlords together with the inventory is to be expropriated without indemnification. All the farming establishments are declared national property, and the management of them is carried on under the control of the state by the labourers organized in councils of management consisting of landless labourers and half-proletarians (owners of parcels of land).

The overproduce of the farming (after the wants of the labourers are satisfied) goes to provide for the population of the towns.

The labourers are workers of the state with a fixed and sufficient pay. They provide the towns with food stuffs, and are provided by the towns with all the necessary products of industry.

The property and the means of production belonging to the labouring peasants remain untouched. The burden of debts weighing upon the peasants is removed, and they enjoy all the advantages of an efficient self-government based on the system of the councils.

In regard to the property rights of the peasants numerous “questions” are usually being asked, as we know, and they all tend to a reform of the conditions within the capitalist order of economic life. Such are the questions of the limitation of partition of peasant estates through entailment, the question of credits, of the abolition of “commons” by a communisation of land estates etc. But there is no need to treat all these questions of detail in a revolutionary program. They all fail to the care of the peasants, and the peasants have to settle them with the proletarian state having naturally its voice therein. All these questions may anyhow be left to the nearest future to decide upon them, the more so as they will appear in quite a different light under a fundamentally new state organization. And in the meantime they may be securely put off from day to day.

But there is one question that has a particular interest and has found a revolutionary solution in Russia. All hired labour for the benefit of a private land-owner is prohibited in Russia on principle–to prevent the formation of a new private land ownership of large estates. This seems to be a special means directed against the landed peasants who are unable to cultivate their estates without hired labour. But it is rather questionable whether such a radical interference is necessary in the countries of our zone. Such a law would cause much trouble to the peasants, considering that under the very complicated present conditions the labouring peasant is also unable to do quite without hired labour. On the other hand, in view of the general “shortage of work” in agriculture in most countries under consideration, such a prohibition becomes necessary, as the moment the big farming establishments pass on to an intensive farming and offer better conditions to the labourer, the landed peasant will hardly find any workers at all. The landed peasants would have to reduce their property to such proportions as to enable them to cultivate their land themselves, whereas the remaining land will pass into the hands of the labouring peasants who are suffering from want of land. (It is of no use to nationalize such peasant estates, as after leaving a part to the former owner for his own cultivation, the area is usually too small for a rational farming).

This question ought anyhow to be carefully examined in each country.

COUNTRIES WITH SMALL PEASANT PROPERTY.

In the west of our “Central European” zone lies a region where the large landed property plays but a very insignificant part, and the agrarian conditions are determined all through by small bourgeois property and farming. This region includes western Germany, a part of German Austria, France, Switzerland, Belgium, Holland, and in the south Italy, Spain and Portugal. In Italy conditions are quite peculiar, inasmuch as there still exists a particular form of “latifundium” property, and the peasantry is since a long time in a state of revolutionary upheaval. The “latifundii” are rather small and hardly deserve the name of such according to cast European ideas. They are rarely cultivated on a large scale and are usually leased to peasants who cultivate their portions in an extremely intensified small way of tilling (approaching “garden culture”). The rent terms are very hard for the peasants who, driven to despair, are in constant revolt against such conditions. A change to rational gross agriculture is hardly to be anticipated in a short time under the present conditions. We have to deal here not with the culture of corn but with the culture of rice, vegetables, vineyards and gardening, in some districts with very intensive breeding of cattle. There is nothing to be done in these parts but, following the wish of the worried small peasants, to parcel the latifundii and to leave the land to the peasantry to cultivate.

The revolutionary proletariat has a trusty ally in this peasantry. The only way to lead them on to Communism lies here in a systematic development of comradeship (Genossenschaftswesen).

The conditions in Spain and Portugal are very much the same.

The chances of revolution are less favourable in western Germany and France, in Belgium and Holland, where the small bourgeois proprietorship has a strong standing, and the peasantry is highly conservative, often directly reactionary in all respects. All hope to win the large mass of this peasantry for active revolution must be given up. But there is to be noted that in Belgium, in some parts of western Germany (Baden, the Rhineland, Westphalen and France–the industrial area) the preponderant majority of the population there are workers. In the country the revolutionary proletariat has anyhow an ally in the agricultural labourers who, although not so numerous in this “land of the peasants” as in the districts with a preponderance of large estates, form anyhow a considerable stratum.

The hope to win this peasantry for the ideals of a proletarian revolution by means of propaganda is therefore an illusion. The object to strive for must be that of neutralizing the peasants by a compromise.

The peasants of these countries are even more involved in debts than in “Central Europe”, and the liberation from the slavery of indebtment to financial capital is of the greatest importance for them. People have hardly a general great interest in these countries for the preservation of gross agriculture. There are in some places big establishments of a general agricultural importance (studs, seed grain production etc.) but with such exceptions gross agriculture has no preponderance whatever, and it is not a reactionary step in the economic sense to partition the big estates in these countries, as it will help the existence of the small peasants suffering from want of land.

The difficulty lies in the attitude in regard to the landed peasant. This seems to be chiefly a political question. In the countries where the reactionary landed peasantry is very numerous and very influential because of its numbers (this must be the case in some parts of Bavaria and Wurtemberg, and in the Scandinavian countries), the revolutionary struggle must necessarily turn against the reactionary landed peasantry. And in this movement the small peasantry and the agricultural labourer, who are comparatively many in these districts of the landed peasantry, are sure to side with the proletariat of the towns for a thorough agrarian reform.

In regard to all these regions with a preponderant peasant ownership, it ought to be anyhow remembered and particularly insisted upon, that an expropriation of the labouring peasants who do not exploit anyone’s labour, is by no means a part of the program of the revolutionary Communist proletariat. Whereas in industry the aim of the Communist proletariat is that of the Social Revolution, the expropriation of the expropriators, the country in the districts with a preponderant peasant ownership ought to feel only the political results of the Social Revolution. The system of the councils leading, as mentioned above, by its substance to true self-government offers only advantages and no drawbacks to the labouring peasants, and it might be presumed that a more or less clever propaganda will succeed in convincing even the dullest peasant of these advantages. The chief enemy would probably prove to be the counter-revolutionary clergy–counter-revolutionary out of principle. Most of these countries being Catholic, this enemy is not to be underrated, and he ought to be relentlessly combatted with all possible means.

A separate position is taken by England, as a result of her very peculiar agrarian conditions. There is on one hand the big landed ownership supported by feudal privileges, on the other purely capitalistic agriculture based on a farming system. There is certainly no doubt whatever that the parasitism of the landlords ought to be overthrown. The dictatorship of the proletariat is out of question as long as the landlords dispose of the land on which the English proletariat lives.

How far is the farmer an associate of the landlord, and how far is he his social enemy? A part of the farmers are labouring peasants. The expropriation of the landlords means for them an immediate gain. If the land in England is to be nationalised, the English proletariat, having control of this land, will be able to secure great advantages to the labouring peasants in leasing to them the land on favourable terms, eventually doing away with the rent the peasant had to pay to the landlord.

A different type is represented by another part of the farmers. They are capitalistic enterprisers who are carrying on an extremely intensive management and use hired labour. To get rid of the obligation to pay rent to the landlord is certainly a tempting prospect for these capitalists but they are quite aware that under the Social Revolution their capitalistic property will not remain a “never touch me”. They prefer therefore to support the present conditions.

The fight is thus to be fought against the landlords and the capitalist farmers as well, whereas the labouring peasant farmers and the landless labourers are the allies of the revolutionary proletariat.

Whether this is an advantage for England to keep up gross agriculture organized up till now on a capitalist basis, or it is more desirable to partition the land among the agricultural labourers and the labouring peasants, we do not undertake to judge. It behooves the English Communists carefully to examine these questions, which will suddenly require an imperative solution at the outbreak of the revolution, and to answer them.

Our object, as mentioned above, was in the first place to point to the urgent need of a clear program in regard to the agrarian conditions. There are unfortunately still enormous gaps in this respect, the Communist parties having in most countries necessarily neglected these questions more than anything else. This is not meant to be a reproach. There were certainly urgent tasks which had absorbed all their energy. But time is pressing. There is no certainty about any country in Europe but that “tomorrow” the Communist Party will be faced with a situation forcing it to assume the power, whether it likes it or not. And it won’t do if these parties will be helpless to cope with the problems of the agrarian conditions.

The example of Russia should be a lesson on how difficult these problems are, and how important a consistent attitude in regard to them is for the success of the Social Revolution, for the triumph of our Communist ideal.

Let us hope that the International Congress will help towards an urgent solution of these questions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/old_series/v01-n11-n12-1920-CI-grn-goog-r3.pdf