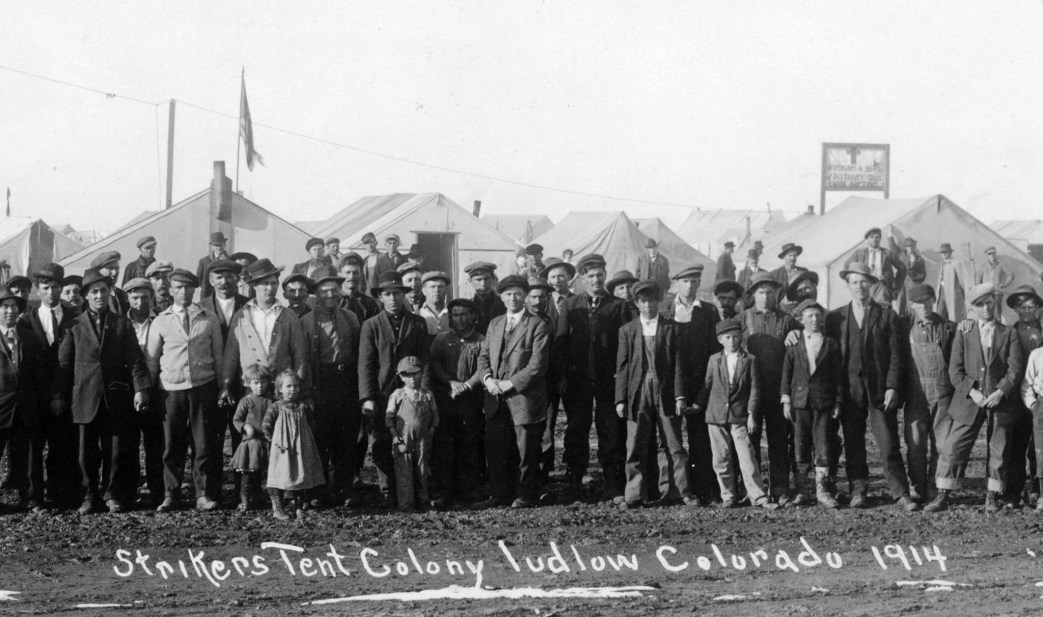

Arguably John Reed’s finest work this side of Russia, an article that is also the best early account of its subject, one of the defining struggles of the U.S. labor movement, the Colorado Mine war that saw the Ludlow Massacre of April, 1914. Arriving shortly after on assignment from Metropolitan magazine (not a left paper, but we are making this exception), Reed investigated the epic strike, life in the tent colonies, the Baldwin-Felts, mass murder, and strikers’ collective resistance in this lengthy, scrupulously enraged essay from a master journalist entirely in his element. First full transcription. A classic.

‘The Colorado War’ by John Reed from The Metropolitan. July, 1914.

HERRINGTON (Attorney for the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company): Just what is meant by “social freedom” I do not know. Do you understand what the witness meant by “social freedom,” Mr. Welborn?

MR. WELBORN (President of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company): I do not. From the testimony before the United States Congressional Investigating Committee.

I got into Trinidad about ten days after the massacre at Ludlow. Strolling up and down the main street, talking in little groups on the corners, lounging in and out of strike headquarters, were hundreds of big, strong-faced miners in their Sunday best. They sauntered along quietly, good-naturedly, hailing one another across the street in foreign tongues like a crowd of farmers come in for the country fair. The noticeable thing was there were no women. The women didn’t come out of their cellars for several days later…

It was a bright, sunny day. Stores and moving picture shows were open, street cars and automobiles and ranchers on horseback went by. Policemen stood twirling their clubs on the corners just as if three nights before a lawless mob with rifles had not tramped the streets and prepared for a desperate house-to-house battle with the militia. Towering over the town to the east rose the great snow-covered rock of Fisher’s Peak; to the north and west began the steep foothills, rocky and covered with scrub pines, in whose canyons lay the feudal coal towns, occupied by armed detectives with machine guns and searchlights.

A man came bursting into strike headquarters and said: “Three scab-herders coming down the street. Don’t know whether they’re coming here or—.” The strikers all tried to get out of the door at once. On the sidewalks I saw that the moving crowd had stopped–frozen–and that all eyes were in one direction. The life of the town was suddenly paralyzed. In the hush the clatter of a passing horse sounded unnaturally loud.

Three militiamen were hurrying toward the station. They walked in the middle of the street, with their eyes on the ground, joking nervously and loudly. They walked between two lines of men on the sidewalks–two lines of hate. The strikers spoke no word; they never even hissed. They just looked, stiffening like hunting dogs, and as the soldiers passed they closed up silently, instinctively, behind them. The town held its breath. The streetcars stopped running. You couldn’t hear anything but the silent tramping of a thousand feet and the shrill voices of the militiamen. Then the train came along and they boarded it. We straggled back. The town sprang to life again.

At the Trades Assembly Hall, where they fed the women and children, school had just let out. The children were singing one of the strike songs:

There’s a fight in Colorado for to set the miners free.

From the tyrants and the money-kings and all the powers that be;

They have trampled on the freedom that was meant for you and me,

But Right is marching on.

Cheer, boys cheer the cause of Union, The Colorado Miners’ Union;

Glory, glory to our Union;

Our cause is marching on.

On the school blackboard someone had written: If a pious hypocrite goes slumming for Christ in New York and goes gunning for miners in Colorado, where does the uplift come in? If he endeavors to suppress white slaves in New York while fostering conditions favorable to the traffic elsewhere, does it buy him anything in ‘the Sweet Bye and Bye’?”

I asked who wrote that, and they told me a Trinidad doctor who had no connection with the union. That is the extraordinary thing about this strike: that nine out of ten business and professional men in the coal district towns are violent strike sympathizers. After Ludlow, doctors, ministers, hack drivers, drug store clerks, and farmers joined the fighting strikers with guns in their hands. Their women organized the Federal Labor Alliance even among women whose husbands are not union men, to provide food and clothing and medical attendance for workers on strike. They are the kind of people who usually form Law and Order Leagues in times like these; who consider themselves better than laborers, and think that their interests lie with the employers. Many Trinidad shopkeepers had been ruined by the strike. A very respectable little woman, the wife of a clergyman, said to me: “I don’t see why they ever made a truce until they had shot every mine guard and militiaman, and blown up all the mines with dynamite.” That was indicative, for this class is the most self-satisfied…

There is nothing revolutionary about this strike. The strikers are neither socialists, anarchists nor syndicalists. They do not want to confiscate the mines nor destroy the wage system; industrial democracy means nothing to them. They consider the boss almost a god. Humble, patient, and easily handled, they had reached a desperation of misery in which they did not know what to do. They had come to America eager for the things that the Statue of Liberty in New York harbor seemed to promise them. They came from countries where law is almost divine, and here, they thought, was a better law. They wanted to obey the laws. But the first thing they discovered was that the boss, in whom they trusted, insolently broke the laws.

To them the union was the first promise of happiness and of freedom to live their own lives. It told them that if they would combine and stand together they could force the boss to pay them enough to live on, and make it safe for them to work. And in the union they discovered all at once thousands of fellow workers who had been through the fight themselves, and were now ready to help them. This flood of human sympathy was an absolutely new thing to the Colorado strikers. As one Mexican said to me: “We go out despairing and there comes a river of friendship from our brothers that we never knew!”

A large part of those who are striking today were brought in as strike-breakers in the great walkout in 1903. Now in that year more than seventy per cent of the miners in southern Colorado were English speaking: Americans, English, Scotch, and Welsh. Their demands were practically the same as the present ones. Before that, every ten years, back to 1884, there had been similar strikes. Militia and imported mine guards wantonly murdered, imprisoned and deported out of the state hundreds of miners. Two years before the 1903 strike, six thousand men were blacklisted and beaten out of the mines, in defiance of the state law, because they belonged to the union. In spite of the eight hour law, no man worked less than ten hours, and when the miners went out Adjutant-General Sherman Bell of the militia suspended the right of habeas corpus, remarking: “To hell with the Constitution!” After the strike was broken ten thousand men found themselves blacklisted, for the operators made a careful study of people most patient under oppression, and deliberately imported foreigners to fill the mines, carefully massing in each mine men of many different languages, who would not be able to organize. They policed their camps with armed guards, who had the right of trial and sentence for any crime.

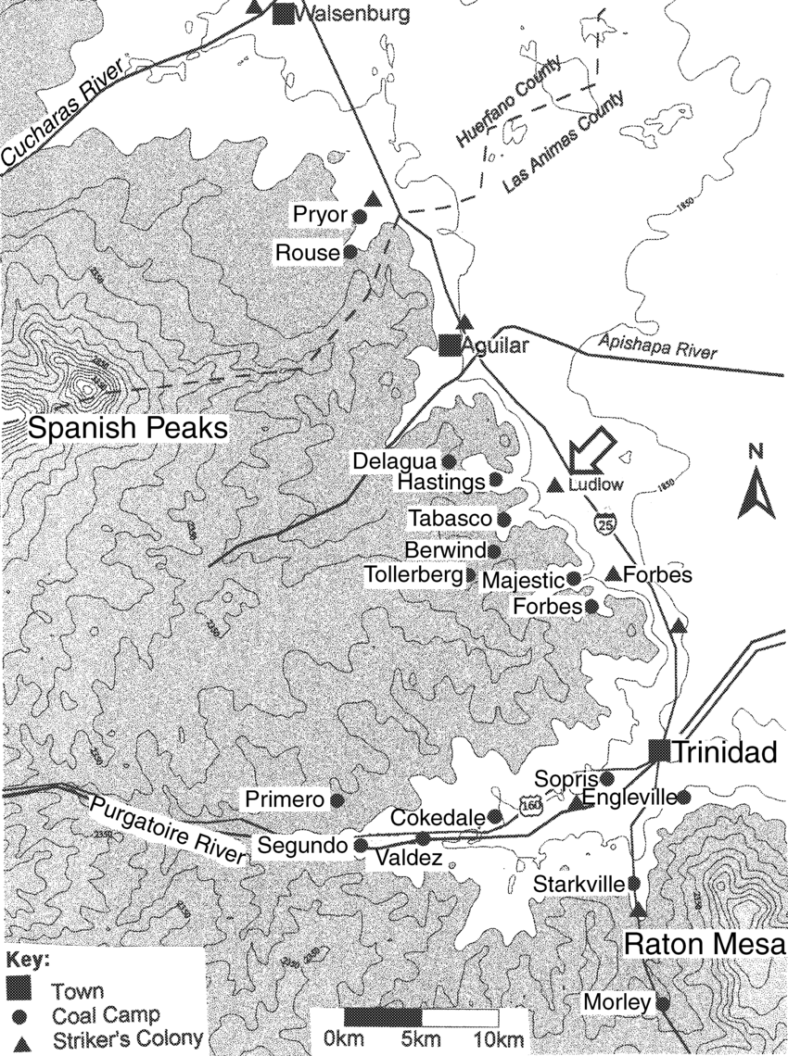

Now, in order to understand the strike, the geography of the southern Colorado district is important. Two railroads run directly south from Denver to Trinidad. To the cast stretches a vast, flat plain, far over the borders of Kansas. westward lie the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, running (roughly) north and south, and beyond them are the magnificent snow peaks of the Sangre de Cristo range. It is in the canyons between these foothills that most of the mines lie, and around these mines are feudal towns–the houses of the workmen, the stores, saloons, mine-buildings, schools, post offices–all on private property, all fortified and patrolled as if in a state of war.

Three big coal companies–the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company, and the Victor American Fuel Company–produce sixty-eight percent of all the coal in the state, and have advertised that they represent ninety-five percent of the output. They naturally also control the prices and the policy of all the other coal companies in the state. Of these, the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company produces forty percent of all the coal mined there, and of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company Mr. Rockefeller owns forty percent of the stock. Mr. Rockefeller absolutely controls the policy of the coal mining industry of Colorado. He said on the stand that he trusted absolutely in the knowledge and ability of the officers of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. He testified that he knew nothing of the conditions under which his miners worked, and that he left all to President Welborn and Chairman Bowers. They in turn testified that they knew nothing of the conditions under which the miners worked, but that they left all that to their subordinates. They did not even know how much stock Mr. Rockefeller held. And yet these men dared to go on the witness stand and say that the miners had no grievances, but were “a happy family!”…

There has been a good deal of talk about the high wages paid to miners. As a matter of fact, most department store clerks get more. A coal miner, a man who actually digs the coal, was paid so much a ton for the pure coal dug, separated from impurities, loaded on cars and pushed out of the mine. The operators give glowing accounts of miners making $5 a day. But the average number of working days a year in Colorado was 191, and the average gross wage of a coal digger was $2.12 a day. In many places it was much lower. Men with a “pull” with the company made high wages; others have been known to work eight days without making money enough to pay for their blasting powder. For they must buy that themselves. They had to pay a dollar a month for doctor fees, and in some places for a broken leg or arm $10 more. Anyway, the doctor only visited the mine every two weeks or so, and if you wanted him any other time you had to pay for an extra visit.

Many of these mine towns were incorporated towns. The mayor of the town was the mine superintendent. The school board was composed of company officials. The only store in town was the company store. All the houses were company houses, rented by the company to the miners. There was no tax on property, and all the property belonged to the mining company…

According to the State Labor Commissioner, from 1901 up to 1910 the number of people killed in coal mines in Colorado, as compared with the rest of the United States all together, was two to one; from 1910 up to the present time it is 3 1/3 to one. It was conclusively shown that the coal companies refused to take any precautions for the safety of their employees until they were forced to by law, and that even after that they refused to obey the recommendations of the State Mine Inspector…

The coroner of Las Animas County is the head of an undertaking-establishment officially employed by the coal companies, in which at least two coal company officials owned shares not long ago. His juries in these great accidents consisted of company employees chosen by the mine superintendents. In five years of unprecedented disaster, only one coroner’s verdict in Las Animas County laid the blame on the company. You see, these verdicts were particularly valuable to the operators, because they disposed of the danger of damage suits. There haven’t been any damage suits in that county for ten years.

This is a slight indication of the way in which the coal companies control politics in Las Animas and Huerfano counties. District attorneys, sheriffs, county commissioners, and judges were practically appointed in the offices of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company. The people could not secure a delegate to the convention to nominate a justice of the peace without telephoning to Denver and asking permission of Cass Herrington, political manager for the Colorado Coal and Iron Company…After the 1903 strike the United Mine Workers had been wiped out of the country. In 1911 they re-established a branch office in Trinidad. From that time on there were rumors of a strike, and it is only from that time that the mine operators began partially to obey the laws. But most of the abuses were not corrected, and the miners realized at last that in order to secure any permanent justice from their employers they must be able to bargain with them collectively.

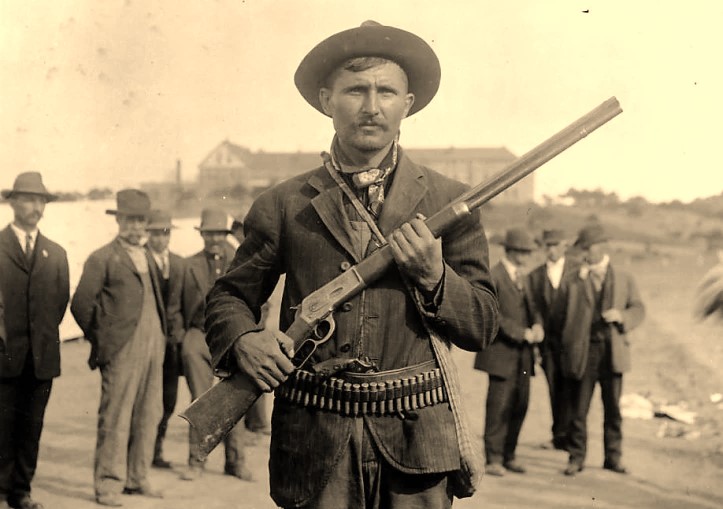

The United Mine Workers did everything they could to avoid the strike. They appealed to Governor Ammons to call a meeting of the operators to confer with them concerning the demands of the men; the company officials refused to meet them, and have so refused ever since. Then a convention of operators and employees was called at Trinidad, and an appeal was made to the employers to meet their men and listen to their grievances. For answer, the operators began to prepare for war. They set in motion their powerful machine for breaking strikes–a merciless engine refined by thirty years of successful industrial struggle. Gunmen were imported from Texas, New Mexico, “\Vest Virginia, and Michigan–strike-breakers and guards who had had long experience in labor troubles, soldiers of fortune, army deserters and ex-policemen. W.F. Reno, chief detective for the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, recruited in the basement of a Denver hotel. To those that could shoot he gave rifles and ammunition and sent them down to the mines. The notorious Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency of strike-breakers was engaged, and many of their men, under bond for murder in other states, were made deputy sheriffs in the southern counties. Anywhere from twelve to twenty machine guns were shipped to the mines and put at their disposal…

At the convention in Trinidad, September 16, delegates from all the mines in the district unanimously voted to call a strike on September 22. They demanded recognition of the union, a ten percent advance in wages, an eight-hour day, pay for all “dead work,” check weighmen, the right lo trade at any store they pleased and to choose their own boarding-place and doctor, enforcement of the Colorado mining laws, and the abolition of the guard system…

The United Mine Workers announced that they would establish tent colonies to take care of the strikers, and, in the face of open menaces by the mine officials and the guards that they would repeat the slaughter and deportation of the 1903 strike, the miners began to arm themselves…

There was a blizzard of snow and sleet on September 23. It was bitter cold. Early in the morning the guards made the rounds of the mines, asking the people whether or not they were going to work. When they answered no they were told to get out. At Tabasco guards came into the houses and threw women and children out into the snow. dumping their furniture and their clothes on the wet ground. At Tercio the workmen were given an hour to leave town: their furniture was thrown out into the street and they were followed out of the mine by guards, abusing them and threatening them with rifles. For fifty miles the mouths of canyons belched groups of men, and women with babies in their arms, and children trudging in the snow. Some had wagons, and long trains of broken-down hacks and carriages, piled high with the possessions of many families, straggled along the many roads toward the open plain.

At Pryor the company had offered special inducements for miners to build and own their own houses on the company grounds. They were ejected from these, and the women told by the mine guards to “Get to hell out or we’ll burn you out!” In West Virginia the operators had given strikers four days to leave. In Colorado it was twenty-four hours. Nobody was prepared. They were driven ruthlessly down the canyon without their clothes or furniture, and when wagons were sent back for their property, in many places, as at Primero, they were not allowed to get it.

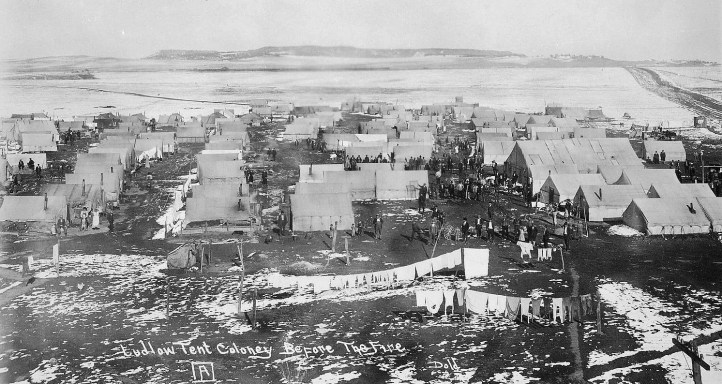

And the tents had not arrived. Out on the cold plain, with the snow and sleet falling, huddled hundreds of refugees: men, women, and children, at the places where their leaders told them to gather. Still the tents did not come. Some of them remained for two days without shelter, digging holes in the ground and burrowing into them like animals, with nothing to eat or drink. There was a frantic raid on the tent stores in Denver, and along the base of the foothills for fifty miles the tent colonies began to rise, white in the white snow. It was like the migration of a race. Out of 13,000 miners at work in Colorado before the strike, 11,000 were out. The colonies were planted strategically at the mouths of the canyons leading up to the mines, to watch the roads by which strikebreakers might be brought in. Besides the big Ludlow colony, there were others at Starkville, Gray Creek, Suffield, Aguilar, Walsenburg, Forbes, and five or six other places.

Mother Jones was up and down the district all this time, making speeches, encouraging the strikers to protect themselves, taking care of children, helping fix up tents, and nursing sick people. The operators in the meanwhile were shouting for the militia. They said that violence would soon break out and that Mother Jones was a dangerous agitator and ought to be deported from the state. Governor Ammons replied that if the local authorities could not handle the strike, the militia would certainly be sent, but that it would not on any account be used to allow the operators to import strike-breakers nor to intimidate miners.

“I intend,” he said, “to put an end to the inflammatory statements of Mother Jones. I will see that she is held in such a way that she cannot talk to the entire country as a prisoner. She will not be allowed to advertise strike conditions outside of the state with the extravagant language she has been using in the coal regions.”

Emma F. Langdon, state secretary of the Socialist Party, announced publicly: “If they harm one gray hair on Mother Jones’ head, I shall issue a call for the good women of Colorado to organize themselves and march on the city of Trinidad, if necessary, to free her.”

From that day to this not a single word has been heard of the Socialist Party of Colorado, although shortly afterward, Mother Jones was imprisoned and held incommunicado for nine weeks in Trinidad.

The first step was to make deputy sheriffs of all these mine guards and detectives. The superintendents of the mines phoned the sheriff how many deputies they needed, and the sheriff sent blank commissions by mail. Union officials asked Sheriff Grisham to deputize a few strikers. He replied: “I never arm both factions…”

Sheriff Jeff Farr reported that strikers had mounted a hill 500 feet high, overlooking Oakview mine, and fired a thousand shots into the buildings. But the newspapermen who investigated found only three bullet holes, and those horizontal. Then a Greek striker got into a personal altercation with Camp Marshal Bob Lee, of Segundo, a notorious killer once connected with the Jesse James outlaws–and the Greek shot first. Everywhere the mine-guards were trying to make trouble. At Sopris they dynamited a company house and tried to blame it on the strikers; but, unfortunately, a man in the plot gave it away. It was expensive for the coal companies–this maintenance of an army. They wanted the militia to do their dirty work at the expense of the state. And also, the strikers· tent colonies interfered seriously with the importation of workmen to run their mines.

The largest of these colonies was at Ludlow, lying at the crossing of the two roads leading to Berwin and Tabasco on one hand and Hastings and Delagua on the other. There were more than twelve hundred people there, divided into twenty-one nationalities, undergoing the marvelous experience of learning that all men are alike. When they had been living together for two weeks, the petty race prejudices and misunderstandings that had been fostered between them by the coal companies for so many years began to break down. Americans began to find out that Slavs and Italians and Poles were as kind-hearted, as cheerful, as loving and as brave as they were. The women called upon one another, boasting about their babies and their men, bringing one another little delicacies when they were sick. The men played cards and baseball together….

“I never did have much use for foreigners before I went to

Ludlow,” said a little woman. “But they’re just like us, only they can’t speak the language.”

“Sure,” answered another. “I used to think Greeks were just common, ignorant, dirty people. But in Ludlow the Greeks were certainly perfect gentlemen. You can’t ever say anything bad to me about a Greek now.”

Everybody began to learn everybody else’s language. And at night there would be a dance in the Big Tent, the Italians supplying the music, and all nations dancing together. It was a true welding of peoples. These exhausted, beaten, hard-working people had never before had time to know one another….

It is almost impossible to believe that this peaceful colony was threatened with destruction by the mine-guards. They were not utter villains. They were only hardened characters acting under orders. And orders were that the Ludlow colony must be wiped out. It stood in the way of Mr. Rockefeller’s profits. When workingmen began to understand one another as well as that, the end of exploitation and blood-money forever was in sight. And Ludlow colony had been established about a week when the gunmen began to threaten that they would come down the canyon and annihilate the inhabitants.

All the visiting, the playing of games and the dances stopped. The colony was in an abject state of terror. There was no organization, no leaders. Seventeen guns and pistols of various kinds had been procured, and very little ammunition. With these, the men of the colony stood guard over their women and children all the long, cold nights, and from the hill above Hastings a searchlight played ceaselessly on the tents….

All through the last week in September streams of people poured out of the canyons into the tent colonies, bringing stories of how they had been thrown out of their houses into the snow and their furniture broken, and the men beaten up and driven down the road at the point of a rifle; and all that week strikers going to get their mail in the mining town post-offices were beaten and shot at and refused the right to travel on the country roads. Word came that the colonists at Aguilar were in terror of their lives and were arming to protect themselves. On October 4 armed guards invaded the streets of Old Sopris, which is not on mine property, and at the point of their guns broke up a meeting of strikers in a public hall. Everywhere searchlights played all night on strikers’ tents, preventing the women and children from sleeping, and driving the men out twenty times a night to defend themselves against the always feared attack. On the 7th of October it came.

Some strikers went up to Hastings to get their mail. They

were cursed and refused admittance to the post-office. As they walked back along the road one of the Hastings guards fired two shots over their heads, both of which struck tents in the colony. A few minutes later an automobile containing B.S. Larson, chief clerk of the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, stopped on the road near the foothills. Twenty shots were fired into the tents. Immediately the colony boiled with shouting, furious men. Only seventeen of them had guns, but the rest armed themselves with rocks and lumps of coal and sticks and swarmed out onto the plain, without plan, without leader. Their appearance was a signal for a volley from the hill above Hastings and from a stone house near the mouth of Hastings canyon. The women and children rushed out of the tent colony and stood fully exposed. Before the furious onslaught of the half-crazed strikers, the guards retreated into the hills. Then the fighting stopped and the men straggled hack, worn out with rage and swearing that they were going up and shoot up Hastings that night. But their leaders argued them out of it.

The next morning, about breakfast time, someone fired upon the tents from a passing freight-train, and that night the searchlight searched the colony all night, until at four A.M. one of the strikers shot it to pieces. That morning the strikers strolled over as usual to get their mail and watch the train come in. Some of them were playing catch in the baseball field east of the station, when a shot fired from Hastings Hill landed right in the middle of them. One hundred men ran yelling across the field to get their guns, and before they could find them shots began to come from a steel railroad bridge. The strikers came swarming down the track toward the bridge. Forty or fifty ran ahead without any weapons except their bare hands, and the rest. straggled along, putting the wrong ammunition into their various makes of gun and trying to make out where the firing came from. They huddled on a coal heap beside the station, uncertain what to do, ignorant of where the firing came from. All this time a fusillade poured from the steel bridge. But the front rank of the armed strikers advanced to Water Tank Hill and, throwing themselves on the ground, blazed away wildly. Suddenly someone shouted, “The militia is coming! The militia is coming! It’s a trap! Back to the tent colony! Back to the tent colony!” Crowding and pushing, in a panic, firing back over their shoulders as they ran, the strikers poured back along the track, but not until a rancher, MacPowell, who had been perfectly neutral to both sides, was shot from the steel bridge while riding home.

But the shooting from the steel bridge continued. Then a northbound train stopped at Ludlow, and Jack Maquarrie, special agent for the Colorado and Southern Railroad, told the newspaper reporters that “there was a bunch of deputies down there in the cut trying to start something.”

It is interesting to know that the militia had been on the train at Trinidad an hour before the fighting started, and that at the first shot the train left for Ludlow.

Three strikers were wounded. Frantically that afternoon the colonists began digging rifle-pits, for upon the arrival of the militia at Ludlow station the guards and deputies had swarmed down from the hill and from the steel bridge, and were boasting that they had taken Ludlow and that before night they would take the tent colony. It was another night of terror for the strikers. No one slept. The men lay in the rifle-pits until daylight–some two hundred of them. Only seventeen were armed with rifles; the rest had butcher knives, razors and axes. But the next day the guards returned to the hills, shouting that some night soon they would come down and kill all the red-necks.

Two days later three guards in an automobile emptied their automatic pistols into the tent colony at Sopris. Four days after that the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company mounted a searchlight and a machine gun on the hill above Segundo. A drunken guard who insulted a woman was badly beaten up there, and that same night the machine gun fired on the town for ten minutes. The next day 48 strikers, peacefully picketing the Starkville mine, which is owned by James McLaughlin, brother-in-law of Governor Ammons, were arrested, forced to march twelve miles on foot between double rows of armed guards into Trinidad, and thrown into jail.

The outrages continued. In Segundo, Baldwin-Felts detectives invaded the Old Town, which is not on mine property, and broke down the door of a private house with an ax, on the pretext of searching for arms. In Aguilar, mine-guards searched the strikers’ headquarters at the point of their rifles, and in Walsenburg Lou Miller, a notorious gunman with five murders to his credit, went around the streets with six armed companions, beating up union men. A.C. Felts, manager of the Baldwin-Felts Detective Agency, arrived on the scene and immediately ordered the construction of an armored automobile, mounted with a machine gun, in the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company’s steel plant at Pueblo.

Too late the union officials tried to get guns for the strikers.

All the ammunition stores had been already cleaned out by the operators, so that by October 15 the twenty-five men at Forbes tent colony, for example, had only seven guns and six revolvers-all of different makes–and very little ammunition. Forbes tent colony lay along the road at the mouth of the canyon leading up to Forbes mine. This place had been fired on several times by snipers from the hills, especially after strikers had refused to allow workmen to pass up to the mine. The men of the colony became so alarmed for the safety of their women and children that they constructed a separate camp for them about three hundred yards away.

On the morning of the 17th of October, a body of armed horsemen galloped down the Ludlow road and dismounted in a railroad cut near the colony. At the same time Felts’ armored automobile appeared from the direction of Trinidad, swung around and trained its machine gun immediately on the tents. Astonished and terrified, the strikers swarmed out, dragging their guns with them, but a guard named Kennedy, afterward an officer in the militia, approached with a white flag, shouting:

“It’s all right, boys; we’re union men.” And as the strikers lowered their guns, he said:

“I want to tell you something.” They clustered around him to hear what he had to tell them. He cried suddenly: “What I wanted to say was that we are going to teach you red-necks a lesson!” and, lowering the white flag, he dropped on the ground. At the same time the dismounted horsemen fired a volley into the group, killing one man instantly. In a panic, the strikers poured back to the tents, across the field to a gulch where they had agreed to go in case of attack, and as they ran the machine gun opened up on them. It riddled the legs of a little boy who was running between the tents, and he fell there. The strikers immediately began to fire back, and the battle kept up from two o’clock in the afternoon until dark. Every time the wounded boy tried to drag himself in the direction of the tents, the machine gun was turned on him. He was shot not less than nine times. The tents were riddled, the furniture in them shot to pieces. A little girl, the daughter of a neighboring farmer, was coming home from school. She was shot in the face. At nightfall the shooting stopped and the attacking party withdrew, hut all that night the strikers did not dare venture back to their tents…

The terror caused by the brutal attack of the “death special” had about subsided when, five mornings later, the strikers woke up to see it planted in the same position as before, the murderous machine gun trained again on the colony, and three other machine guns within a radius of two hundred yards, completely surrounding the colony. As the sun came up, armed men swarmed down from the hills in every direction. There were more than a hundred of them. Under cover of the guns Under-Sheriff Zeke Martin, of Las Animas County, marched up to the tents and ordered all the men to form in single file and go down to the railroad track. Cursed at and beaten, they were lined up there with the machine gun of the “death special” covering them. Then began a search of the tent colony in which all the strikers’ arms were taken, their trunks smashed open, their beds torn to pieces, and money and jewelry stolen. The house of a rancher nearby, a Civil War veteran, who was not connected in any way with the strikers, was entered and ransacked, and his wife was threatened that “if she harbored any more union men her house wouldn’t be standing long.”

That same night a mob of infuriated miners surrounded a Baldwin-Felts detective in Trinidad and threatened to lynch him…

By this time the strikers in every colony from Starkville to Walsenburg had determined to rely no more upon the faith or promises of the peace officers, but to get guns and protect their wives and children from the murderous assaults of the mineguards the only way they could. It was a decision born of desperation; few of them had ever seen a gun, much less shot one–and most of them were from countries where the authority of the Law is little Jess than divine…

There were daily threats now by letter, telephone and armed men shouting from the hills that some night soon all the guards from all the mines would come down the canyons and destroy the tent colonies. In Ludlow colony people lived in a continual panic. The men went to Trinidad, begging from house to house for old rifles, rusty pistols–anything, in fact, that would shoot.

And it was a strange collection of odd and obsolete weapons that was gathered together in the tent colony. On the advice of their leaders, the colonists dug cellars under their tents, where the women and children could be removed in case of an attack. The enforced watching at night, the insults and occasional shots from mine-guards, the beating up of union men whenever they dared go alone outside the colony at night, and the unceasing stories of outrages by the gunmen all along the line, wrought the strikers up to such a pitch that only the pleadings of their leaders prevented them from attacking and annihilating the guards. They returned the latter’s threats, and there was terror, too, in the mine-camps.

On the 26th of October the dam of wrath broke. For several days the Ludlow colonists had been expecting an attack, and the settlement was picketed night and day by armed sentries. On Saturday morning, the 25th, some strikers who had been over to the railroad station reported the arrival of a new searchlight to replace the one shot to pieces on the ninth. Several men exclaimed that it ought not to be permitted to be set up again to spy on them, but the strike leaders insisted that the searchlight must not be interfered with. So it was not molested. Toward afternoon the telephone rang and a voice said: “I’m talking from Hastings. Look out down there. A big gang has left here on horseback to start something, and a lot more are going to hide at the mouth of the canyon and come out on you when the first shot is fired.” Almost the same minute, one of the sentries came running in. “They’re coming! The deputies are riding down the canyon-a big bunch!” The men in the camp began to run for their arms. “Don’t fight!” cried the leaders, “it’s a plant! They’re trying to start something!”

“Well, they’ll get something then!” answered the men. “They’re not after us,” pleaded another. “Leave ’em alone, boys. They’re coming in to take that new searchlight back to Hastings.”

“No, they don’t,” shouted a man. “I ain’t a-going to have that searchlight on my tent all night. Come on, boys!” And as they hesitated there, uncertain whether to attack or not, the question was decided for them. Twenty armed and mounted men emerged from the canyon road, riding toward the depot. Suddenly one deliberately lifted his rifle and shot–once. It was enough. The strikers poured out of the colony toward the railroad cut and the arroyo, so as to draw the guards’ fire away from the tent colony, and began to shoot as they went. Immediately the reserve forces that had been hidden in the canyons poured out, and a battle began which lasted until dark. Outnumbered and outshot, the strikers retreated slowly eastward and north, stopping at the C. and S. Steel bridge. And there the guards tried to dislodge them, when darkness fell; the guards retreated in the night toward the hills and the strikers, some of them, followed. That night almost the entire body of the strikers took to the hills. By Sunday morning, the twenty-sixth, Tabasco mine was besieged by shooting strikers, entrenched on the hilltops. That night word went out up and down the tents of seven thousand strikers that at last the boys had got the guards where they wanted them at Ludlow; and all night long men sifted into camp, walking sometimes twenty-five miles with their guns on their shoulders.

The guards telephoned to Trinidad for help. Twice that day trains were made up in Trinidad to carry deputies and militia to the reinforcement of Tabasco, but in both cases the train crew refused to carry them. Thirty-six Walsenburg deputies were hurried to Trinidad on a special train, shooting on the Ludlow tents as they passed, and were immediately created deputy sheriffs of Las Animas County in the Coronado Hotel.

But the strikers, without organization or leadership, soon got tired of battle and straggled back across the plain to the tent colony, singing and shouting with the elation of victory. There was a grand banquet and a dance that night, at which all the visitors were entertained, and the warriors told their stories over with much boasting and adulation. But in the midst of the festivities word came that the guards were loading a machine gun into a wagon and were coming down the canyon. The dance broke up in a panic, and all night no one slept. However, there wasn’t even a shot fired by either side on the plain until dawn, although desultory rifle-fire in the hills indicated that some of the wandering bands were still “sniping” at the guards.

But in the morning it all began again with volleys from the hills. At the same time, authoritative information was phoned from Trinidad of the approach of an armored train of three steel cars equipped with machine guns, such as was driven through Cabin Creek to rain steel into the West Virginia strikers’ tents last year. Five hundred men streamed across the plain to wait for that train; they paid no attention to the shooting from the hills.

And when the train came within half a mile of Ludlow, such a hail of shots met it that it was forced to back into Forbes mine. A northeast snow blizzard blotted out the world that night.

And in the darkness the strikers left their tents and took to the hills–about seven hundred of them. Before dawn on the twenty-eighth they opened a vicious fire on Berwind and Hastings, killing over ten mine-guards and deputies. Closer and closer they drew–fiercer and fiercer waxed their shooting. Telegraph and telephone wires were cut, and a gang was ordered to blow up the railroad leading up from Ludlow. At Tabasco, also, the strikers drove the guards and their families into the mouth of the mine. If they had been permitted to finish what they had begun so thoroughly, there is no doubt that the guards in those three mines would have all been shot. But through the storm couriers came running from the Ludlow colony.

“Stop fighting,” they ordered, “and come back to the tents quick. The governor has called out the National Guard!”

And so they straggled back down from the hills and across the plain, discussing this new complication. What did it mean? Would the soldiers be neutral? Would the strikers be disarmed? Would they be given protection against the gunmen? Those that had been in other big strikes were mortally afraid. But the leaders reassured them for the moment, and that evening the men from other tent colonies went home, and the Ludlow men gave in their guns to their leaders so that they could be handed over to the soldiers in the morning. But morning came and no soldiers, nor any news of them. At the same time a man called up from Trinidad to say that seven automobile-loads of armed deputies had left for Ludlow, vowing vengeance for the attack on Hastings and Berwind. And as the day wore on, other and worse rumors multiplied.

“We are lost!'” they cried. “The soldiers are coming to take away our rifles. They will shoot us down. That is what they always do in strikes. And first the guards will come tonight. We must send away the women and children.” And so the wives and mothers and children were put on the Trinidad train and the men settled down in their empty camp.

“Let’s show them we are men. Let us revenge ourselves upon the mine-guards, before the soldiers come and kill us. We’ll do some real fighting.”

There was only a little band now armed, not more than a hundred. Without plans or leaders they sallied out into the storm before dawn; but the guards were now on the alert, and greatly outnumbered the strikers. About seven in the morning they came wearily back and threw themselves on the floor to sleep.

“This militia story was just a trick to leave us unprotected,” they said. “There aren’t any soldiers coming. Give us all the arms and ammunition and we will wait for the guards here!” And they waited for the end, in cold despair.

But on the morning of the thirty-first the militia troop-train reached a point three miles north of Ludlow, where it stopped while General Chase came to the Ludlow colony under a flag of truce. He informed the leaders of the colony that Governor Ammons’ orders were to disarm both sides, to preserve the peace, and that the militia was not to be used to help the operators bring in strikebreakers nor to intimidate the strikers.

The leaders communicated these promises to the men, who, overjoyed at the end of their reign of terror, eagerly turned over their guns to be delivered to the militia, and happily sent for their women and children. So relieved and grateful were they to the soldiers that they planned a magnificent reception.

At the request of the strikers the militia marched into Ludlow in dress uniform. The whole Ludlow colony in its Sunday best went a mile out across the snowy, sunlit plain to the east to meet them. Ahead danced a thousand children, gathered from all the colonies, dressed in white and singing the strike song. A double brass band followed, and then twelve hundred men and women with American flags. They formed two dense, cheering, friendly lines, through which the highly pleased National Guard marched to its camping place…

Chase established his headquarters at Ludlow, the militia camp being across the railroad tracks from the Ludlow tent colony and between it and the mines. He announced that disarmament of both sides would begin at once, and to prove his good faith to the strikers he disarmed the mine-guards first. Then he asked the strikers for their guns. They handed over thirty-two–twothirds of all the firearms in the colony. The reason why the rest were not surrendered was because of a rumor from Trinidad that the guns taken from the strikers there had been turned over to the mine-guards at Sopris and Segundo. “Yes,” said the militia captain in command at Trinidad, in answer to a question from the strike leaders, “I did tum them over. You see, we have not enough soldiers in the field to protect these mines, and your fellows up there are pretty excited, they tell me.” Word also came from Aguilar that the guns taken from the mine-guards and Baldwin-Felts detectives had been returned to them for the same reason. Shortly afterward the Ludlow guns were handed over to the guards at Delagua, Hastings, Berwind, and Tabasco. But the strikers didn’t make any fuss about it.

The relations between the Ludlow colonists and the militia were very friendly. Teams of soldiers and miners played baseball in the snow and went hunting rabbits together. The strikers gave a dance for the militia in the Big Tent, and the guardsmen visited the different tents and shared in the life of the colony. They were always welcome to dinner. The strikers, too, circulated freely around the militia camp. Among the miners were a number of Greeks and Montenegrins who had fought in the Balkan War. Sometimes the militia officers let them take guns and drill and were astonished at their cleverness.

But this state of things lasted only about two weeks. The main argument of the operators in demanding the militia was that many of the strikers in the tent colonies would be willing to return to work if they could be assured of protection, the operators stating that as soon as the militia entered the field there would be a steady rush of strikers back to the mines. But upon the arrival of the National Guard nothing of the sort happened. Hardly a man deserted. So the operators had to use other tactics. The attitude of the militia suddenly changed. General Chase, without any warning, announced that the Ludlow strikers were concealing arms and would have to give them all up within twenty-four hours. The militia were ordered to keep away from the tent colony. On November 12, militia and mine-guards together, suddenly made a search for concealed arms in the houses of the strikers at Old Segundo. Trunks were smashed and money and jewelry stolen. Word came from Trinidad that three of the most notorious Baldwin-Felts guards had been enrolled as state soldiers. General Chase began to make his rounds in a Colorado Fuel and Iron Company automobile. Strikers were told to keep away from the railroad station and the public roads, so that there would be no dispute between them and strike-breakers going to work in the mines.

There was no state appropriation for paying the National Guard. The coal operators offered to finance it, but Governor Ammons decided it was “not proper.” He did, however, allow the Denver Clearing House, through its president, Mr. Mitchell, to advance $250,000, and that was an indirect way of allowing the coal companies to buy the militia, for Mr. Mitchell is the same president of the Denver National Bank who threatened to call the loans of Mr. Hayden, president of the Juniper Coal Company, if he made terms with the union.

It soon began to be apparent what course the militia intended to pursue. Although martial law had not been declared, and, as a matter of fact, never was, General Chase issued a proclamation in Trinidad creating “the Military District of Colorado,” with himself in command, and announced that “military prisoners” would be arrested and disposed of by the militia under his command. The first of these “military prisoners” was a miner who came up to a soldier in the streets of Trinidad and asked where he could join the union…

Chase openly began a campaign of tyranny and intimidation. Just as in former strikes, wholesale arrests followed, and batches of thirty-five to one hundred men and women at a time were thrown into jail without charges and held indefinitely as “military prisoners.” Strikers going to the post-office at Ludlow to get their mail were arrested. Union men caught talking to strike breakers were clubbed and jailed. Adolph Germer, Socialist organizer of the United Mine Workers, was placed under arrest when he stepped from the train at Walsenburg, and Mrs. Germer was insulted in her own house by drunken officers. The mineguards, emboldened by the open favor of the militia, began again their interrupted course of making trouble. On the night of November 15, they fired several volleys into the strikers’ houses at Picton. A soldier forbade Mrs. Radlich to go for her mail to the Ludlow post-office, and when she answered him defiantly he knocked her down with the butt-end of his rifle. Lieutenant Linderfelt met a seventeen-year-old boy at the Ludlow station, accused him of frightening militiamen’s horses, and beat him with his fists until he couldn’t walk.

Even these measures were not violent enough for the operators. Newspapermen at the state capitol heard a group of operators reviling Governor Ammons: “You God damned coward,” they said; “we are not going to stand for this much longer. You have got to do something, and do it quick, or we’ll get you!” And the embodiment of the will of the people of the sovereign state of Colorado answered: “Don’t be too hard on me, gentlemen! I’m doing it as fast as I can.” And then the door closed. Shortly after that General Chase issued another proclamation guaranteeing protection for all men wishing to go to work in the mines, and that he intended to establish a secret military court to try and sentence all offenders against the laws laid down by him as Commander of the Military District of Colorado. I think it was that same night that some striker, outraged by the intolerable insolence of Baldwin-Felts Detective Belcher, shot and killed him on the streets of Trinidad. Thirty-five military prisoners were crammed into the stinking cells of the county jail and held there indefinitely without adequate food, water, or heat. Five of them were brought before the military court and charged with murder, and when they would not confess they were tortured. For five days and five nights icy water was thrown on them, and they were prodded with bayonets and clubbed so that they could not sleep. At the end of that time an Italian named Zancanelli broke down and signed his name to a “confession,” written by the military officers, which he afterward repudiated and which, of course, was proven false.

The Union made one last desperate attempt to get the operators and strikers together for a conference, but the former refused absolutely to pay any attention to the appeal. General Chase announced that the patience of the militia was exhausted. The strikers discovered to their surprise that a train containing several hundred strike-breakers had been brought into the state and escorted by the militia to the mines. They called up Chase about it. He admitted that Governor Ammons over the telephone had privately modified his order against importing strikebreakers. That was the first the strikers knew of it.

Then began the bringing in of thousands of workmen from the East. Workingmen were assured that there was no strike in Colorado. They were promised free transportation and high wages. Some were hired to work in coal mines, and others were lured west on a land scheme.

Some of these people were union men. Few wanted to be “scabs.” But they were told they would not be allowed to leave until they had worked off their transportation and board. An Italian at Primero who tried to escape down the railroad track was shot in the back and killed. Another at Tabasco was murdered because he refused to go to work. Those who really wanted to keep their jobs were forced to work for weeks for nothing. One man, who had some money, paid his transportation in cash, and though he worked twenty days and was credited on the company’s books with coal enough to earn him $3.50 a day, he was told at the end of that time that he made only fifty cents. The militia acted under the orders of the mine superintendents, refusing to allow anybody to leave who had not a “clearance” from the company. You had to have a pass to get in and out of the mine camps. Hundreds of strike-breakers escaped at night over the hills in the snow and sought protection and shelter in the strikers’ tent colonies, where they were given union benefits and a tent to live in…

The lawlessness and brutality of the soldiers increased. Two drunken militiamen, one an officer, invaded the house of a rancher while he and his wife were away, made vile suggestions to two small children, broke open trunks and stole everything of value. Although a complaint was made they were not punished. At Pryor tent colony, a Croatian striker named Andrew Colnar wrote a letter to one of his fellow countrymen who was a strikebreaker, asking him to join the union. The militia arrested Colnar, took him to camp, and set him to work digging a hole in the ground under armed guards. They told him that he was digging his own grave and was to be shot at sunrise. Astounded and terrified, the poor man asked to be allowed to see his family for the last time. They told him that he couldn’t, and that if he didn’t dig his own grave he would be shot immediately. Colnar fainted in the pit that he had dug, and when he came to was cursed and beaten.

This seems to have been a favorite pastime with the militia. Tom Ivanitch, a Pole, was pulled off the train at Ludlow while going to Trinidad and told he must make his grave. There was no charge against him–the militia said they did it for fun!–but he was allowed to write his last letter, and here it is:

“Dear Wife:

“Best regards from your husband to you and my son and sister Mary and little Kate and my brother Joe. I am under arrest and not guilty and I am digging my own grave today. This will be my last letter, dear wife. Look after my children, you and my brother Joe. There won’t be anything more of me unless God helps me. With this world that men have to go innocent and lie in the ground and God bless the ground where I lie. We are digging the grave between the tents and the street. Dear wife and brother Joe, I am telling you to look after my children. Best regards to you and the children and brother Joe and motherin-law and sister-in-law Mary Smiljimie and to all that’s living. If I don’t go tonight to Trinidad and see the head men and see if something can be done for us. I think it will be too late. I don’t know what to write any more to say good bye for ever. I see now that I will have to go in the grave. God do justice. I got $5 to put in the letter if somebody don’t steal it. I got $23.30 from Domenic Smircich. That there is written in a book. Let Joe get that. Best regards to all I know if they are living.

“Your husband,

Tom Ivanitch

“I am sorrow and broken hearted waiting for the last minute. When you get the money from the society for the children divide it equally.”

And here is another from an Italian who was set to the same task:

“Dear Louisa:

“Best regards from my broken hearted Carlo. This is the last letter I am writing. That’s all I have to say. Sorrow. Good-bye, good-bye.”

On January 23, the women and children of the strikers held a parade in Trinidad to protest against the imprisonment of Mother Jones, who was then in San Rafael Hospital. They went along gaily enough, singing and laughing, until they turned into Main Street. There, suddenly, a body of militia cavalry blocked their way. “Go to your homes!” they shouted. “Disband! Go back! You can’t pass here!” The women stopped uncertainly, and then surged forward, and the body of cavalry slowly advanced upon them with drawn sabers. All the hate of the strikers for the militia surged up in these women. They began to jeer and shout: “Scab-herders! Baldwin-Felts!” The soldiers rode right in among them, herding them. General Chase himself led them, shouting the vilest epithets. A little sixteen-year-old girl stood in the general’s way. He rode up beside her and kicked her violently in the chest. Furiously angry, she told him to look out what he was doing. Another soldier galloped at her and struck at her with his saber. A groan and a yell went up from the women. General Chase’s horse shied suddenly and the general fell to the ground. The women roared with laughter. “Ride them down! Ride down the women!” screamed the general; and they did. General Chase himself laid open a woman’s head with his sword. The steel-shod hoofs of the horses struck women and children, knocking them down. In a panic, the crowd fled along the street, the soldiers among them, striking and yelling like madmen. Throwing themselves off their horses they launched out like madmen with their fists, knocking down women and dragging them along the street. That day the jail was jammed with more than a hundred military prisoners.

Toward the end of February a subcommittee of the Committee on Mines and Mining of the United States House of Representatives came to Trinidad to investigate the strike. Among other things, the most appalling charges against the militia were made by witnesses. Captain Danks, attorney for the militia, promised that he had a wealth of testimony to confute these charges; but at the end of the hearing he had not even challenged one of them.

On the last day of the investigation, March g, a strike-breaker was discovered dead near the Forbes tent colony. The next day the militia, under Colonel Davis, went to Forbes and completely destroyed the strikers’ colony, tearing down the tents, smashing the furniture, and ordering the strikers to go out of the state within forty-eight hours. He said he had orders from General Chase to “dean out that tent colony,” for the Forbes strikers had been the chief witnesses to militia brutality before the Congressional Committee. More than fifty strikers and their families were turned adrift in the bitterest cold weather of the winter, with no homes to go to and nothing to eat. Two babies died of exposure.

Several days later the militia rounded up ten men from the Ludlow tent colony who had testified against them and marched them up to Berwind. There they beat them, and stood them up against a stone wall with a cannon trained on them, forbidding them to make the least movement and stabbing them with bayonets when they did. They kept them standing there, threatening to shoot them, for four hours, and then got a rawhide whip and lashed them down the canyon, following them on horseback at a gallop. An old miner named Fyler finally became so exhausted that he couldn’t run. He stopped, and four soldiers fell upon him and beat him so that he had to crawl back to Ludlow on his hands and knees.

Everything, evidently, was being done to exasperate the strikers. Four times the militia made a pretense of searching Ludlow colony for arms. They would stand two machine guns across the railroad track trained on the colony, and, rushing through the tents, would drag out the men and line them up on the open plain, a mile away, under another machine gun, while the soldiers rode through the camp stealing everything of value they could lay their hands on, tearing up the floors, bursting in the doors and insulting the women.

I don’t mean to say that the strikers didn’t resent this reign of terror; but I do mean to say that they committed no violence against the militia except to jeer at them and call them names. Nevertheless, they were aroused to a pitch of exasperation that even their leaders couldn’t promise to control long. Their homes destroyed and invaded, their women assaulted, robbed and beaten and insulted every minute, they determined that they would not submit any further. General Chase refused to allow the Forbes tent colony to be rebuilt, and the strikers threatened to do it anyway; and this time, they said, they would be prepared to resist in such a manner that the militia would not destroy their homes until they were killed. Frantically, then, all along the fifty miles of tent colonies the strikers began to buy arms. And suddenly, on March 23, the militia was recalled from the field.

The $250,000 advanced by the Denver Clearing House to pay the soldiers had long since been exhausted. Moreover, State Auditor Kenehan had made an investigation, and had found such appalling graft and dishonesty among both officers and privates that he refused to honor the certificates of indebtedness. Many of the soldiers were mutinying because they had received no pay. The mine-guards, in uniform, went around the country contracting debts, and signing notes that the state would pay them. There was no discipline whatever. The officers could not control their men.

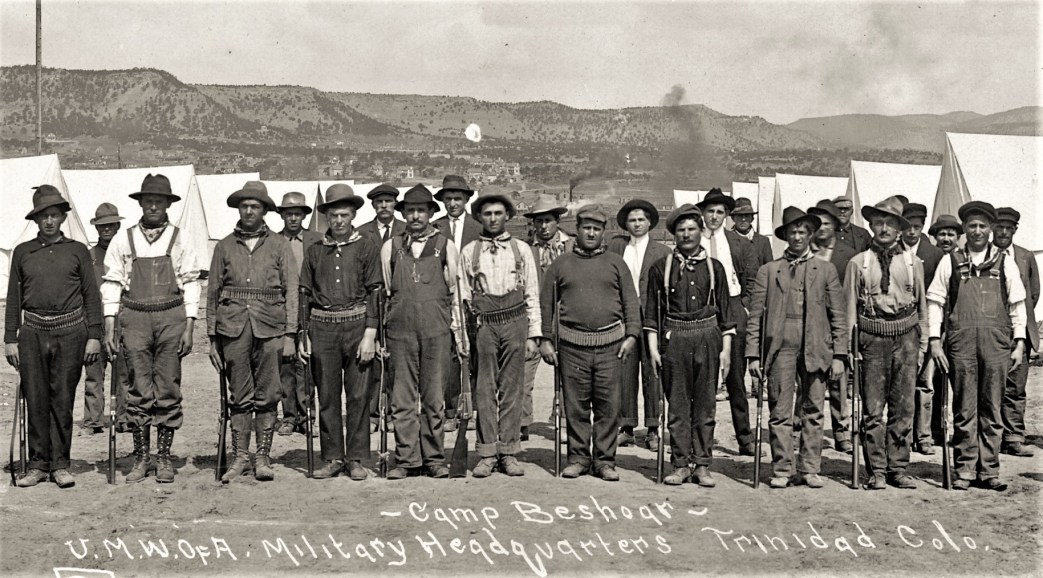

But before they left two companies of militia were enrolled Company B in Walsenburg and Troop A in Trinidad. These companies were composed almost entirely of mine-guards and Baldwin-Felts detectives. They were paid by the coal companies. The most hardened strike-breakers of the other companies were drafted into a new company–facetiously called Company Q-which had its headquarters at Ludlow. These three companies remained in the field. Many of the men were professional strike breakers who went to work in the mines in their militia uniforms, leaving their guns at the pit mouth…

Sunday, April 19, was the Greek Easter, and the Greeks at Ludlow tent colony celebrated it. Everybody celebrated it with them, because the Greeks were loved by all the strikers. There were about fifty of them, all young men and all without families. Some of them were veterans of the Balkan war. Because Louis Tikas, a graduate of the University of Athens, was the gentlest and bravest and most lovable of the Greeks he became the leader of the strikers, too…

It was a fine day, the ground was dry, and the sun shone. At dawn the Ludlow people were up, larking around among the tents. The Greeks started to dance at sunrise. They refused to go into the big tent, but on a sun-swept square of beaten earth they set Hags in the ground; and, dragging their national costumes from the bottom of their trunks, they danced all morning the Greek dances. Over on the baseball diamond two games were in progress, one for the women and one for the men. Two women’s teams had decided to play; and the Greeks presented the women players with bloomers as an Easter gift. So, with laughter and shouting, the whole camp took a holiday. Children were everywhere, playing in the new grass on the plain.

Right in the middle of the baseball games, four militiamen came across the railroad track with rifles in their hands. Now, it had been customary for the soldiers to come over and watch the strikers play; but they had never before brought their arms. They slouched up to the men’s diamond and took up a position between first base and the home plate, leveling their rifles insolently on the crowd. The strikers paid no attention for a while, until they saw that the soldiers were standing right on the line where the runners had to pass, and interfering with the game. One of the men protested, and asked them to move to one side so that the runners could get by. He also said that there was no necessity for pointing their rifles at the crowd. The militiamen insolently told him it was “none of his damned business,” and that if he said another word they would start something. So the men quietly moved their diamond and went on playing. But the militiamen were looking for a row, so they went over to the women’s game. The women, however, were not so self-contained as the men. They jeered at the guardsmen, calling them scab-herders, and said that they were not afraid of the guns, and that two women with a pop-gun could scare them to death. “That’s all right, girlie,” answered one militiaman. “You have your fun today; we’ll have ours tomorrow.” Shortly after that they went away.

When the baseball game was over the Greeks served lunch for all the colony. The old meeting-tent was not good enough for them on their great holiday. They had magnificently sent to Trinidad and bought new tents for the occasion; tents that had never been used. There was beer for the men and coffee for the women; and whenever a Greek drank he rose and sang a Greek song instead of a toast. Everybody was very happy, because this was the first real day of spring they had had. At night there was a ball; and then about ten o’clock a man came in and whispered to the other men that the militia were riding silently through the colony and listening at the walls of the tents.

The dance broke up. For several days rumors, and even threats, had reached the colonists that the militia intended to wipe them out. In the dark those who had arms gathered in the office tent. There were forty-seven men. They determined not to tell the women and children; because, in the first place, if there was to be a fight, of course, the militia would not attack the tent colony, but would allow the strikers to get out into the open plain, as they had in the fall, and fight them there; in the second place, there had been many such threats and nothing had come of them. But just the same they mounted guard around the camp that night; and when morning came everything was quiet, so they went back to the tents to sleep.

About 8:45 the same militiamen who had interrupted the ball game the day before swaggered into camp. They had come, they said, to get a man who was being held against his will by the strikers. Tikas met them. He assured them that there was no man of that name in the colony; but they insisted that Tikas was a liar, and that if he didn’t produce the man at once they would come back with a squad and search the colony.

Immediately afterward Major Hamrock called up Tikas on the telephone and ordered him to come to the militia camp. Tikas answered that he would meet the major at the railroad station, which was halfway between the two camps, and Hamrock said all right. But when Tikas got there he noticed that the militia were buckling on their cartridge belts and taking up their rifles; that everywhere was war-like activity, and that two machine guns covering the tent colony had been planted on Water Tank Hill. All of a sudden a signal bomb exploded in the militia camp. The strikers had also seen the machine guns and heard the sound of the bomb; and as Tikas reached the railroad station he saw the forty-seven armed men leaving the tent colony and filing off toward the C. and S.E. Railroad cut and the arroyo. “My God, major! What does this mean?” cried Louis. Hamrock seemed very much excited. “You call off your men,” he said nervously, “and I’ll call off mine.” “But my men aren’t doing anything,” answered Louis; “they are afraid of those machine guns up on the hill.” “Well, then, call them back to the tent colony,” screamed Hamrock. And Louis started off on a run to the tents, waving a white handkerchief and shouting to go back. A second bomb went off. He had got halfway, and the strikers had halted in their march, when the third bomb burst; and suddenly, without warning, both machine guns pounded stab-stab-stab full on the tents.

It was premeditated and merciless. Militiamen have told me that their orders were to destroy the tent colony and everything living in it. The three bombs were a signal to the mine-guards and Baldwin-Felts detectives and strike-breakers in the neighboring mines; and they came swarming down out of the hills fully armed-four hundred of them.

Suddenly the terrible storm of lead from the machine guns ripped their coverings to pieces, and the most awful panic followed. Some of the women and children streamed out over the plain, to get away from the tent colony. They were shot at as they ran. Others with the unarmed men took refuge in the arroyo to the north. Mrs. Fyler led a group of women and children, under fire, to the deep well at the railroad pump house, down which they climbed on ladders. Others still crept into the bullet-proof cellars they had dug for themselves under their tents.

The fighting men, appalled at what was happening, started for the tent colony; but they were driven back by a hail of bullets. And now the mine-guards began to get into action, shooting explosive bullets, which burst with the report of a six-shooter all through the tents. The machine guns never let up. Tikas had started off with the Greeks; hut he ran back in a desperate attempt to save some of those who remained; and stayed in the tent colony all day. He and Mrs. Jolly, the wife of an American striker, and Bernado, leader of the Italians, and Domeniski, leader of the Slavs, carried water and food and bandages to those imprisoned in the cellars. There was no one shooting from the tent colony. Not a man there had a gun. Tikas thought that the explosive bullets were the sound of shots being fired from the tents, and ran round like a crazy man to tell the fool to stop. It was an hour before he discovered what really made the noise. Mrs. Jolly put on a white dress; and Tikas and Domeniski made big red crosses and pinned them on her breast and arms. The militia used them as targets. Her dress was riddled in a dozen places, and the heel of her shoe shot off. So fierce was the fire wherever she went that the people had to beg her to keep away from them. Undaunted, she and the three men made sandwiches and drew water to carry to the women and children. Early that morning an armored train was made up in Trinidad, and 126 militiamen of Troop A got on board. But the trainmen refused to take them; and it was not until three o’clock in the afternoon that they finally found a crew to man the train. They got to Ludlow about four o’clock, and added their two machine guns to the terrible fire poured unceasingly into the tent colony. One detachment slowly drove the strikers out of their position at the arroyo, and another attempted in vain to dislodge those in the railroad. Lieutenant Linderfelt, in command of eight militiamen firing from the windows of the railroad station, ordered them to “shoot every God damned thing that moves!” Captain Carson came up to Major Hamrock and reminded him respectfully that they had only a few hours of daylight left to bum the tent colony. “Burn them out! Smoke them out!” yelled the officers. And their men poured death into the tents in a fury of blood lust.

It was growing dark. The militia closed in around the tent colony. At about 7:30, a militiaman with a bucket of kerosene and a broom ran up to the first tent, wet it thoroughly, and touched a match to it. The flame roared up, illuminating the whole countryside. Other soldiers fell upon the other tents; and in a minute the whole northwest corner of the colony was aflame. A freight train came along just then with orders to stop on a siding near the pump house; and the women and children in the well took advantage of the protection of the train to creep out along the right-of-way fence to the protection of the arroyo, screaming and crying. A dozen militiamen jumped to the engineer’s cab and thrust guns in his face yelling to him to move on or they would shoot him. He obeyed; and in the flickering light of the burning tents the militia shot at the refugees again and again. At the first leap of the flames the astounded strikers ceased firing; but the militia did not. They poured among the tents, shouting with the fury of destruction, smashing open trunks and looting.

When the fire started Mrs. Jolly went from tent to tent, pulling the women and children out of the cellars and herding them before her out on the plain. She remembered all of a sudden that Mrs. Petrucci and her three children were in the cellar under her tent, and started back to get them out. “No,” said Tikas, “you go ahead with that bunch. I’ll go back after the Petruccis.” And he started toward the flames.

There the militia captured him. He tried to explain his er rand; but they were drunk with blood lust and would not listen to him. Lieutenant Linderfelt broke the stock of his rifle over the Greek’s head, laying it open to the hone. Fifty men got a rope and threw it over a telegraph wire to hang him. But Linderfelt cynically handed him over to two militiamen, and told them they were responsible for his life. Five minutes later Louis Tikas fell dead with three bullets in his back; and out of Mrs. Petrucci’s cellar were afterward taken the charred bodies of thirteen women and children.

Fyler, too, they captured and murdered, shooting him fifty four times. Above the noise of the flames and the shouting came the screaming of women and children, burning to death under the floors of their tents. Some were pulled out by the soldiers, beaten and kicked and arrested. Others were allowed to die without any effort being made to save them. An American striker named Snyder crouched dully in his tent beside the body of his eleven-year-old boy, the back of whose head had been blown off by an explosive bullet. One militiaman came into the tent, soaked it with kerosene and set it on fire, hitting Snyder over the head with his rifle and telling him to beat it. Snyder pointed to the body of his boy; and the soldier dragged it outside by the collar, threw it on the ground, and said: “Here! Carry the damned thing yourself!”

The news spread north and south like wildfire. In three hours every striker for fifty miles in either direction knew that the militia and mine guards had burned women and children to death. Monday night they started, with all the guns they could lay their hands on, for the scene of action at Ludlow. All night long the roads were filled with ragged mobs of armed men pouring towards the Black Hills. And not only strikers went. In Aguilar, Walsenburg, and Trinidad. clerks, cab drivers, chauffeurs, school teachers, and even bankers, seized their guns and started for the front. It was as if the fire started at Ludlow had set the whole country aflame. All over the state labor unions and citizens’ leagues met in a passion of horror and openly voted money to buy guns for the strikers. Colorado Springs, Pueblo, and other cities were the scenes of great citizens’ meetings which called upon the governor to ask the president for Federal troops. Seventeen hundred Wyoming miners armed themselves, and wired the strike leaders that they were ready to march to their help. Letters were received by the Union from cowboys, railroad men, and I.W.W. locals representing a thousand laborers offering to march across the country and help. Five hundred Cripple Creek miners left the mines and started eastward for the Black Hills…

Meanwhile at Ludlow the militia went quite mad. All day they kept the machine guns steadily playing on the scorched and blackened tent colony. Everything living attracted a storm of shots: chickens, horses, cattle, cats. An automobile came down the country road. In it were a man and his wife and daughter touring from Denver to Texas. They did not even know there was a battle going on. Soldiers turned a machine gun on the automobile for two miles, shot the top off and riddled the radiator. To a newspaper reporter Linderfelt screamed: “We will kill every damned red-neck striker and we’ll get every damned union sympathizer in this district before we finish.” Dead wagons sent out by the union from Trinidad to get the bodies of the women and children were attacked so furiously that they had to turn back. On the still burning ruins of the tents militiamen were seen to throw bodies.

And the strikers, too, were in a frenzy. The United Mine Workers issued a call to arms. By day they lay firing on the summit of the hills in constantly increasing numbers; by night they dug trenches, always getting nearer and nearer to the militia’s positions. On Wednesday Major Hamrock telephoned to the mine guards at Aguilar: “For God’s sake start something!” he said; “they are pouring in on us from all the tent colonies. All the Aguilar strikers arc down here, and you have got to make a play to get them back.” So the guards fired a volley into the Aguilar tents from the windows of the Empire Mine boardinghouse. The effect was astonishing. Three hundred furious strikers and townspeople poured out of the town and swept up toward the mines. Shouting and yelling, they rushed up to the very rifles of the mine guards. They were absolutely resistless. At Royal and No. 9 the guards and strikebreakers fled to the hills. The strikers stormed in and took possession, burning the tipples, destroying the houses, and smashing the machinery with the butts of their rifles. At Empire the general superintendent of the company and some of the guards took refuge in the mine. The strikers sealed them up there, blew up the tipple, and destroyed fifty houses so thoroughly that you could not tell where a house had stood.

All along the line the same thing happened. Strikers’ houses in Canyon City were raked with a machine gun. The strikers captured Sunnyside and Jackson mines and melted the machine gun up to make watch-charms, although they did no other damage. At Rouse and Rugby, four hundred strikers attacked the mines.

Two days after the burning of Ludlow, a reporter, some Red Cross nurses, and the Rev. Randolph Cook of Trinidad, were permitted by the militia to search among the ruins of Ludlow tent colony. The battle was still raging, and the soldiers amused themselves by firing into the ruins as close as they could come to the investigators. Out of the cellar under Mrs. Petrucci’s tent, which Louis Tikas had tried so hard to reach, they took the bodies of eleven children and two women, one of whom gave birth to a posthumous child. There was no evidence of fire in the cellar, but many of the bodies were badly burned. The truth is that they were burned in their tents–several militiamen have confessed to me that the fearful screaming of the women and children continued all the time they were looting the colony–and the soldiers had thrown them into the hole with others who had been smothered by smoke.

But when the rescuers returned to Trinidad they were told that many other bodies were missing, and one striker informed them that near the northeast corner was a cellar in which eighteen people had perished. So on Saturday they returned. By that time the militia had returned to the field, and General Chase was in command. He welcomed them cordially and asked if they had the authority of the Red Cross Society to carry its banner. They said they had. General Chase courteously asked them to wait a minute while he communicated with Denver and found out. Soon he came back. “It’s all right,” he said. “I’ve telephoned to Denver and you can go ahead.” So they started down toward the tent colony. Chase followed them through field glasses from his tent, and as they approached the place where they thought the bodies lay he despatched two soldiers after them to bring them back. The General was furiously angry. Without giving any reason he held them under arrest for two hours, guarded by soldiers. At the end of that time they were marched in in single file before him as he sat at his desk. “You’re a bunch of damned fakers!” he yelled, waving a telegram. “I have just found out from Denver that you have no authority to carry that Red Cross flag. What the hell do you mean by coming out here and trying to bluff me?” The Rev. Cook ventured to protest that that wasn’t fit language to use before ladies. “Pimps, preachers, and prostitutes look all the same to me!” answered the General; “you get to hell out of here back to Trinidad and never come near here again.” And it is true that the Red Cross Society of Denver, in a panic at offending the coal operators, had telephoned to Trinidad after the party left for Ludlow and revoked their authorization to use the Red Cross flag. That night the C. and S. Railroad dumped a cargo of quicklime at the militia camp, and several dis-used wells in the neighborhood were opened. As a matter of fact the strikers themselves have no idea how many people were killed at Ludlow…