Spearheaded with a target of Bass beer, whose chairman was a British army colonel, militants in Ireland waged a battle in its unfinished revolution during the early 1930s to boycott British goods. Aodh MacManus of the newly-formed Communist Party of Ireland analyses the movement and the Party’s relationship with it.

‘The “Boycott British Goods” Movement in the Irish Free State’ by Aodh MacManus from International Press Correspondence. Vol. 13 No. 43. September 29, 1933.

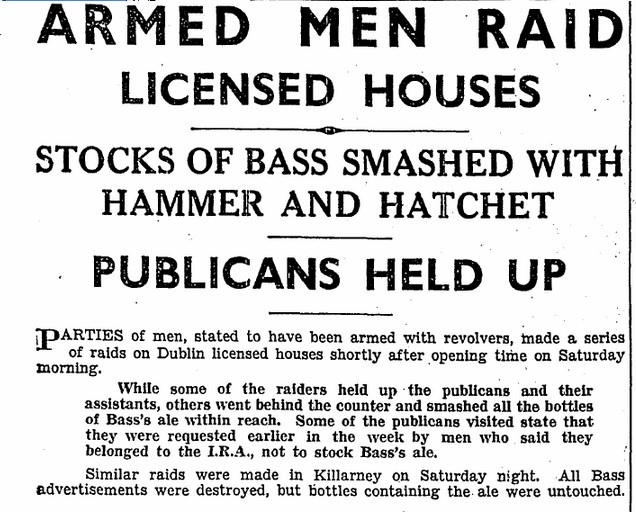

The “Boycott British” struggle is intensifying in the Irish Free State. Wholesale raids on beer houses selling English ale have occurred not only in Dublin, but in almost every part of Southern Ireland. In most cases supplies of Bass ale were destroyed and advertising material relating thereto seized or defaced. Over a score of arrests have taken place in connection with this struggle; the Fianna Fail Government is openly warning militant Republicans that the movement will be ruthlessly dealt with; while republican workers demonstrating outside Dublin courts in sympathy with their comrades on trial have been batoned down by de Valera’s police and dragged into the dock for daring to invade the sanctity of His Majesty’s Free State law.

In this situation it is imperative that the Irish Communists appraise correctly the boycott struggle and make clear to the working masses their attitude towards it.

The boycott movement commenced in the summer of 1932, when British imperialism’s economic strangulation of Ireland was beginning to be sharply felt. The movement was inaugurated by the setting up of a Boycott British League, composed largely of representatives of militant republican organisations. No attempt was made to widen the League on a really mass basis, and no reformist Labour or Trade Union body was affiliated, although the Revolutionary Workers’ Groups (now the Communist Party of Ireland) had a representative on the Executive Committee and from the outset participated actively in the movement. The League achieved little result; its chief activities were the issuing of circulars, the holding of a big mass meeting in Dublin, and the visiting of publicans with a request that they no longer stock Bass’ ale (Colonel Gretton, head of the firm of Bass, was alleged to have said that the Irish should be exterminated; this and the claim that it was better to concentrate on one sphere and deal with it properly led to the confinement of the boycott to the one article). Eventually it became obvious even to the promoters of the League that something was lacking, and like the Arabs it folded its tents and stole silently away.

It is clear that the idea of a boycott of English goods by the Irish people is petty bourgeois in its class roots. It is the method of fighting Britain which springs to the mind of the shopkeeper and the small manufacturer, as combining patriotism with profit. In India, for instance, it is seen to be blatantly a policy of the Indian bourgeoisie, who, so far from using the boycott against Britain, turned it to their own mercenary class advantage and against any serious struggle by the Indian masses. The boycott is not a weapon of the working class. It can in no way lead to a fundamental challenge to British imperialism in Ireland. But does this mean that we oppose the boycott movement and isolate ourselves from it? No. Our task is to deepen and extend the struggle, at the same time pointing out to the Irish masses its weaknesses and deficiencies.

The boycott struggle presents many different features from last year. True it commenced just when the strongest united front struggle was necessary against the Fascist Blue Shirts, and therefore may have served some people as a diversion from the pressing question of anti-fascist mass activity, but the fact remains that the boycott fight has risen to new heights.

The struggle is still being confined mainly to Bass’ ale, but measures on a much wider scale have been taken. The consternation of the de Valera government at this new boycott upsurge may be judged from the Irish Press, the government organ, which after the first Dublin raids asked angrily in an editorial: “What agent-provocateur has done this?” Immediately afterwards there followed arrests in several parts of the country, including Dublin, Cork, Drogheda and Tralee. In Kerry the police were insufficient to hold back the republican workers who demonstrated at the court house during the trial, and a cordon of troops had to be stationed outside with fixed bayonets. In Dublin, on September 8, the court was thrown into turmoil. The Irish Independent of September 9 reports the scenes as follows:

“Some of the young men carried banners with the slogans Should Ireland be held in bondage?–Well done, Kerry and Dublin;’ ‘Irish goods for Irish people–Boycott enemy goods;’ ‘Boycott British goods and courts,’ etc. The banner bearers broke through the police cordons, and both parties (of republicans) joined forces outside the main gates of the court, where there were cries of ‘Up the Republic!’ The police here intervened in force, and a series of baton charges swept the crowd back beyond two strong cordons at each end of the court. Several were injured in the isolated melees, and many of the demonstrators, who frequently stood up to the baton charges and attempted to fight the Gardai, were also injured…Inside the court struggles then took place between the police and the interrupters, who behaved in the wildest manner, some of them escaping from the Gardai and rushing to shake hands with the defendants, who stood up in the dock and responded to the greetings.”

The government organ the following morning commented most ” democratically” on these scenes, which an editorial dubbed “a disgrace.” The Irish Press (September 9) continued:

“We have been bitterly criticised from the Right and from the Left during the last few weeks for standing firmly by the authority of the people’s elected representatives. Now it should be clear to everybody what the course that began in organised attacks on property must lead to minority tyranny or abject chaos.”

De Valera followed up his press organ with a speech at a mass meeting at Dundalk on September 10. After dealing with the merger of the pro-imperialist groups into the United Ireland Party (the “New Empire Party,” the Daily Express happily dubs it) and campaign by big farmers in Waterford to secure an organised refusal to pay rates, de Valera turned his attention to the Boycott League’s activities. Saying that he wanted to declare deliberately that these activities were ‘playing into the hands of the enemies of Irish independence at home and abroad,” he continued:

“I want to warn these Republican enemies of the government. I want to warn them in time that their present course may very well lead to national defeat and disaster, and the end in our time of all our hopes.”

And Mr. Frank Aiken, Free State Minister for Defence, capped de Valera’s warning by assuring the meeting that

“there are sufficient resources and sufficient forces at our control to deal with any rowdy element and its forces.” (Irish Press, September 11.)

It is clear then that the following can be said of the boycott movement:

1. The events in Dublin and Kerry show that it can be turned away from terrorist actions isolated from the masses, and can serve as a bacillus bringing the masses into action against imperialism. It can serve as a lever carrying the struggle forward to a higher plane than is looked for by the Republican leadership. 2. The struggle is rapidly increasing the differentiations between the de Valera government–the main obstacle to any mass struggle against imperialism–and the revolutionary republicans, who everywhere are seeing their comrades arrested and sentenced for anti-imperialist actions.

The Irish Communists therefore must give full support to the Boycott movement. They must fling themselves into the struggle, at the same time making clear its limitations. They must strive to win the leadership of the movement and turn it into mass channels that will bring the Irish working people as a whole into the fight, extending it from one insignificant article to a frontal attack on imperialist interests in the country. The differentiation between the de Valera government and the militant rank and file of the Republicans must be increased; Communists must seize every opportunity and instance to drive home the lessons of the government’s repressive measures. The boycott must be linked to the broad anti-fascist fight. Above all the Communists must raise the class issues involved before the workers. This issue the Boycott League is trying to avoid. The boycott must not become a weapon to assist the Guinness’s, the Jacob’s and other sections of so-called Irish capitalism, the basis of imperialism in Ireland. The issues of wages and conditions in Irish industry, the struggle for the complete overthrow of imperialism leading to the establishment of the Workers’ and Farmers’ Republic of a united Ireland, must be kept constantly before the masses of the Irish working people.

International Press Correspondence, widely known as”Inprecor” was published by the Executive Committee of the Communist International (ECCI) regularly in German and English, occasionally in many other languages, beginning in 1921 and lasting in English until 1938. Inprecor’s role was to supply translated articles to the English-speaking press of the International from the Comintern’s different sections, as well as news and statements from the ECCI. Many ‘Daily Worker’ and ‘Communist’ articles originated in Inprecor, and it also published articles by American comrades for use in other countries. It was published at least weekly, and often thrice weekly.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/inprecor/1933/v13n43-sep-29-1933-Inprecor-op.pdf