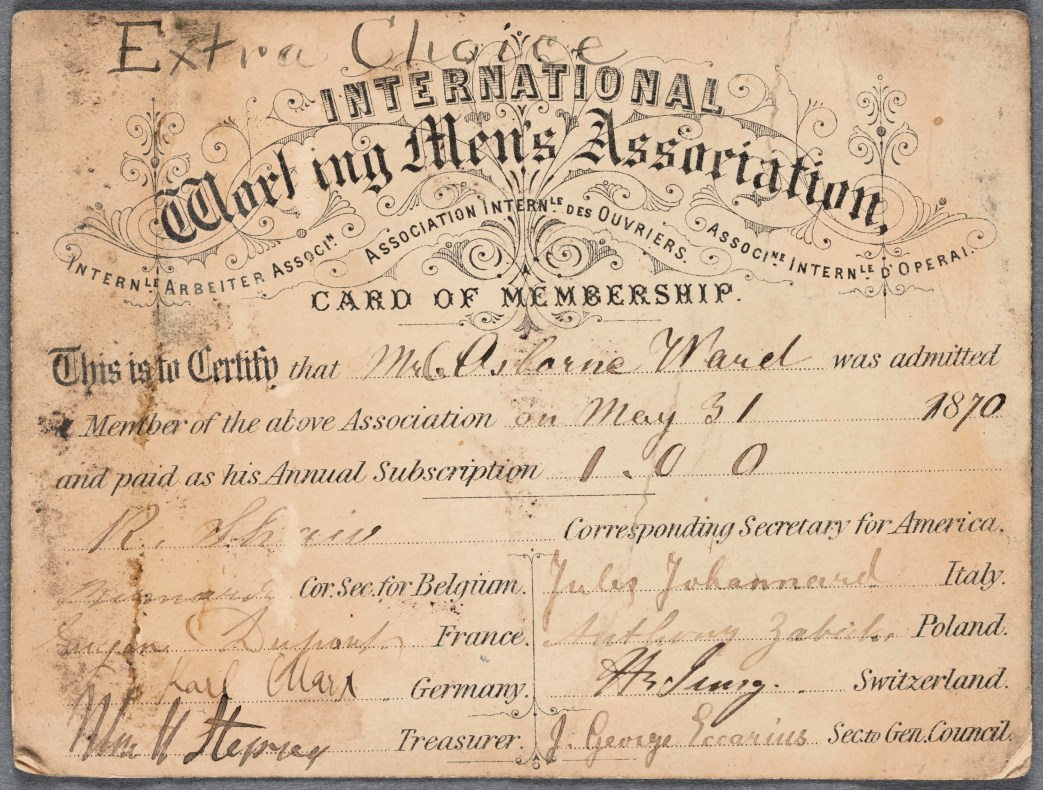

Machinist at the Brooklyn Navy Yard, C. Osborne Ward was a participant in the 1869 Basel conference of the First International. Opposed to the Marxist wing, he was mainly a cooperatist, Ward was, however, a leading native-born working class voice of the International in the U.S. Here he gives his history of the founding of the International Workingman’s Association.

‘The International in England’ by C. Osborne Ward from Workingman’s Advocate (Chicago). Vol. 7 No. 45. July 15, 1871.

In giving you a view of this important organization of workingmen, already memorialized in history, I have reserved, for the last letter, the history of its birthplace–the locality, not of its conception, but of its leap into organized existence, and the place of its head centre and general direction Notwithstanding the importance which attaches to it, by reason of these great events in France, the place of its birth is, of all others, most suggestive; since it is here that its career is marked with its most peculiar and vital characteristic, that of conciliation and agglomeration. This characteristic has, in fact, shown itself to be the signal one of its whole career. England is agitated with awful political throes. These irrepressible agitations are the fruit of an immense but miscellaneous organization of her workmen. She has among her friendly societies a regularly published list of 12,026 societies, containing over a million and a half of workingmen. Her trades unions are 1.250,000 strong. Her co-operative societies are gradually trailing up, until, at my last visit, their numbers had last increased to 300,000; innumerable other and kindred organizations are springing out of this moral soil, whose peculiar fertility is more propitious of late, to emancipation of wages slavery, than to the perpetuation of aristocracies.

But these vast elements of force in the right direction were unknown to each other. Their growth had been based on objects of individual improvement, and their career did not run in parallel lines. There was a relationship in their origin and history, an affinity in character and object, but no amalgamation or affiliation; and while they fought for parallel interests, they harassed each others flanks on the march.

It remained obviously the duty of the International Association of Workingmen to work up these conciliations. The incipient germs of this society are said to be Polish. The noble struggle of the Poles excited, in 1863, the openly expressed sympathy of all civilized people. In Paris and London this sympathy was shared more especially by the working classes. At a moment of high excitement a meeting, mostly of workingmen, was called at St. James’ Hall, London, April 28, 1863. Several French workingmen were present, among whom, Tolain and Fribourg. This meeting gave rise to the International society which was created out of the discussions it excited. The London workingmen invited the foreigners to conferences, and after some consultation it was resolved to hold another meeting. During the time between these meetings, however, an address was drawn up by Mr. Odger to the French sympathizers in Paris, which was received and answered with warmth. The second meeting alluded to was held in the St. Martin’s Hall, September 28, 1864, and was presided over by Mr. Edward Spencer Beesley, and it was here that the International took on material existence and became a thing. It went so far as to appoint a provisional council, and Mr. Odger was elected president. In November this council adopted the rules of the society, and delivered an address. The foresight of the council was manifested in calling an International conference or congress of the delegates from sympathizing workingmen’s societies in all parts of the world.

This celebrated Congress convened at Geneva, Sep. 3, 1866. From that moment the tyrant Napoleon began to dog the International, and the innumerable arrests and annoyances, waged by him and his harpies, are traceable to the monarch’s foresight, in viewing, as he well might, in this ominous organization the hand writing on the wall. It is evident that the same omen was shadowed over the souls of the monarchists in England. Fenianism, which was at that time argued to be a delusion practiced on the Irish, by a ring of sharks to bag their honest contributions, and the aristocracy of England taking advantage of the thus created susceptibilities, pushed their surmise, that they might thus give the International a disreputable smack among the workingmen of England. All these and many more have been the obstacles met by the International, but nothing is insuperable to true progress.

It was not until 1867 that the organization began to show its aptitude and peculiar qualities of affiliation with the older trades unions or organizations of resistance. It was late before it began to show its inherent facility as a conciliating medium between parties on strike in different parts of the world. It was not until 1868 that it began to be practically explained that a strike at Chemnitz, or Geneva, or Basil, or elsewhere, might be supported by subsidies from a fund at London, and that, therefore, there was a great incentive in principle, before all trades unions, no matter of what nationality, to unite in business reciprocity so as to insure success by calculation, as exact as the figures of an almanac, before the strike was determined upon. It began to be estimated through the political lessons taught by the International, that it was perfectly possible to achieve an organization so perfect and so universal, having an understanding so thorough and an object so analogous, that details of business might be profitably applied, in all the lanes and byways of the world where men in masses toil to earn a living. To facilitate this the telegraph was employed, and through it the International has sent many important strike despatches from London to France and Switzerland.

Amalgamations began to be formed by Trades unions, with the international for these purposes of convenience in 1868. The Belgians who possess the faculty of successful combination to a high degree, have turned nearly all their original trades unions into genuine sections of the International. The stubborn adhesion to old forms which characterises the working organizations of Scotland and the north of England, caused the subject of amalgamation to be thoroughly weighed before its adoption by them; and these agitations have not subsided. Several of the unions in the north of England have however led the example, and they will follow one by one as the business facilities over the old isolated system present themselves by test and application.

Although this association is, generally speaking, a strictly business institution and confines its sessions almost exclusively to business objects, yet it has a wide theoretical field, and in this, it is, that it has signalized itself as by far the most remarkable, and launching workingmen’s society in the world.

Interspersed among its business duties, it regularly indulges as a part of its order of business in the propaganda. This propaganda is rigidly observed and is heralded in the following manner:

An annual congress is regularly called. This congress consists of regular delegates sent by the sections or by the central committees, from different parts of the world. At this congress points of the progressive movement are discussed, and by all the delegates conjointly, who determine by vote and adoption those subjects which may be of the most importance for discussion. These points of the reformatory movement which are very radical and often socially revolutionary are reported verbatim as uttered and appear in the Bulletin of the Congress. Copies of this Bulletin are sent to all the sections and the Resolutions adopted by the Congress form the subject of debate in all parts of the world simultaneously. This is the propaganda for the ensuing year. Every year fresh subjects of discussion are furnished by the annual congress, and it will be apparent from this regime that the International society is indeed a most remarkable organization; since by its organizations of working men are taught to discuss and study the same points of radical reform with a multitudinous variety of local applications according to their peculiar circumstances all over the world.

The Chicago Workingman’s Advocate in 1864 by the Chicago Typographical Union during a strike against the Chicago Times. An essential publication in the history of the U.S. workers’ movement, the Advocate though editor Andrew Cameron became the voice National Labor Union after the Civil War. It’s pages were often the first place the work of Marx, Engels, and the International were printed in English in the U.S. It lasted through 1874 with the demise of the N.L.U.

PDF of issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn89077510/1871-07-15/ed-1/seq-1/