Doing this project I have read many great essays, this is one of the best. An exhilarating read from one of the towering artists of the 20th century. Based on a speech to the All-Union creative meeting of employees Soviet cinematography on January 8, 1935 and later reworked into this article ostensibly about the use of montage to create both intellectual depth and emotional weight. To make his point he takes us on a journey, visiting Engels and the Bororo of Brazil, shamanism and the synecdoche, colonialism and the dialectic, James Fenimore Cooper and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl, pars pro toto and Lavater’s physiognomy. Extraordinary.

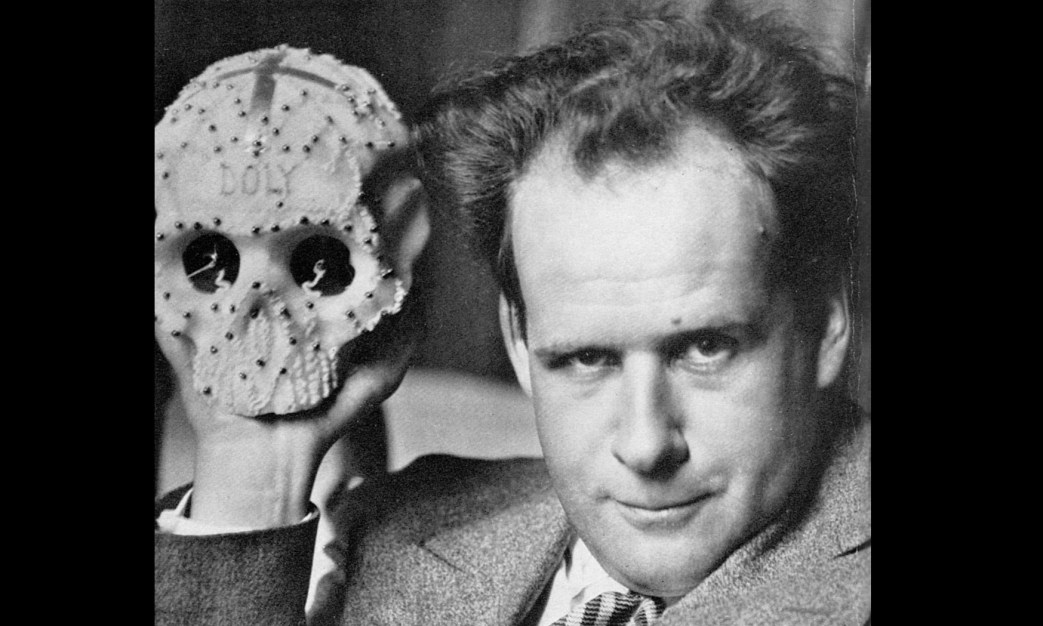

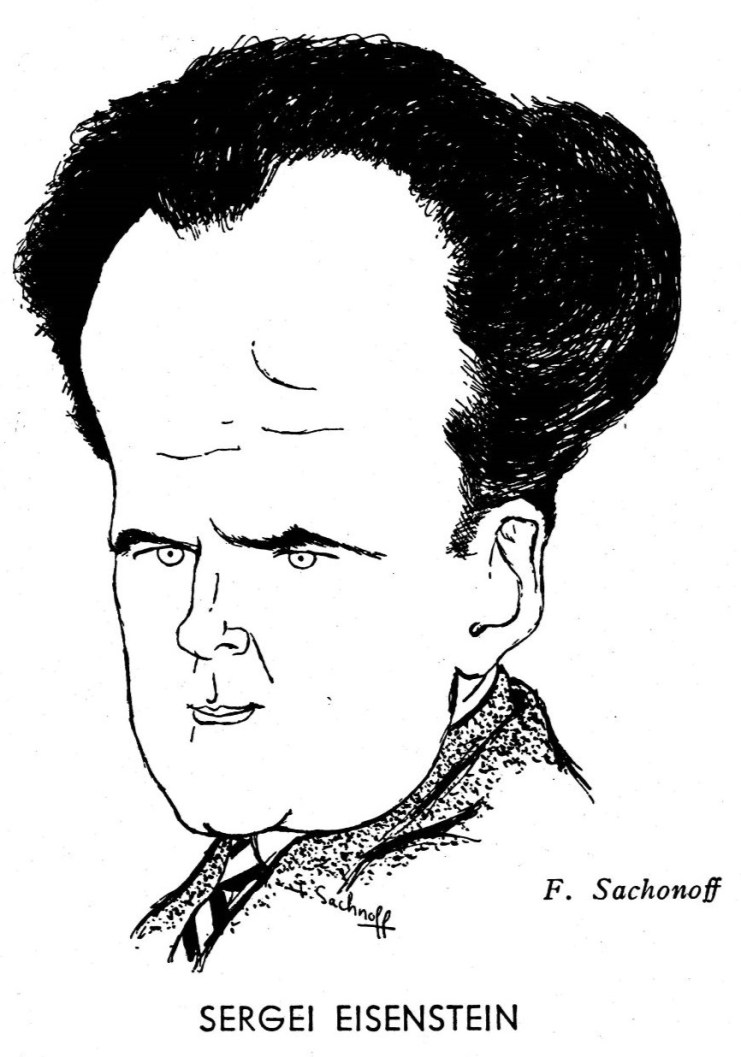

‘Film Forms: New Problems’ by Sergei Eisenstein from New Theatre and Film. Vol. 3 Nos. 4, 5, & 6. April, May, & June, 1936.

I.

Even that old veteran Heraclitus observed that no man can bathe twice in the same river. Similarly no aesthetic can flourish on one and the same set of principles at two different stages in its development. Especially when the particular aesthetic concerned happens to relate to the most mobile of the arts, and when the division between the epochs is the succession of two Five-Year periods in the mightiest and most notable job of construction in the world—the job of building the first Socialist state and society in history. From which it is obvious that our subject is here the aesthetic of film, and in particular the aesthetic of film in the Soviet land. That land in which, in Stalin’s words, cinematography has been designed the most notable of the arts.

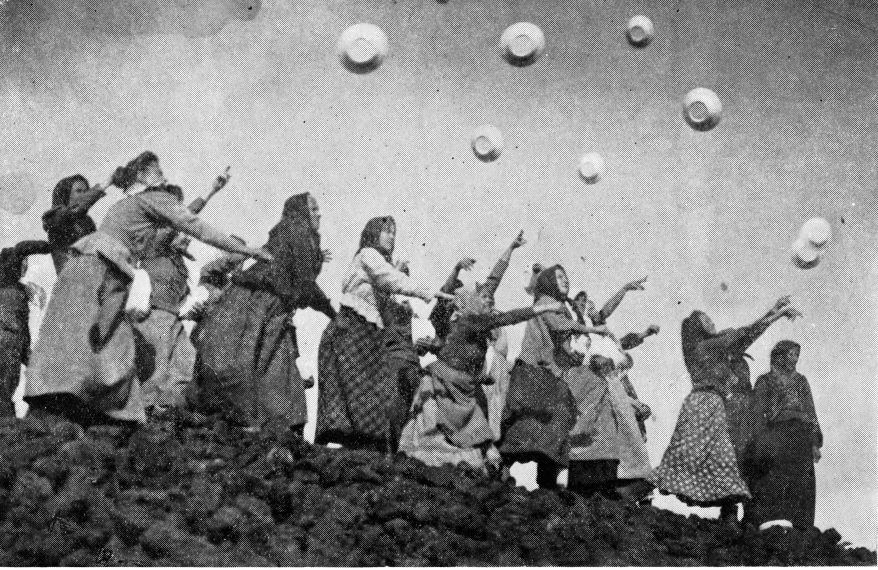

During the last few years a great upheaval has taken place in the Soviet cinema. This upheaval is, first and foremost, ideological and thematic. The high-water mark of the blossoming of the silent cinema was attained under the broadly expansive slogan of mass, the “mass-hero” and methods of cinemato-graphic portrayal directly derivative therefrom, rejecting narrowly dramaturgical conceptions in favour of epos and lyrism, with “type” and episodic protagonists in place of individual heroes and the consequently inevitable principle of montage as the guiding principle of the film expressiveness. But during the last few years the first years, that is, of the Soviet sound-cinema–the guiding principles have changed.

From the former all-pervading mass imagery of movement and experiences of the masses, there begin at this stage to stand out individual hero-characters. Their appearance is accompanied by a change in the construction of the works in which they appear. The former epical quality and its characteristic giant scale begin to contract into constructions closer to dramaturgy in the narrow sense of the word, to a dramaturgy, in fact, of more traditional stamp and much closer to the occidental cinema than the pictures that once declared war to the death against its very principles and methods. The best films of the most recent period (Chapayev, for example) have none the less succeeded in partially preserving the epical quality of the first period of Soviet cinema development, with larger and happier results. But the majority of films have almost completely lost that luggage, comprised of principle and form, which determined in its day the specific and characteristic quality of face of the Soviet cinema, a quality not divorced from the newness and unusualness it bore as reflection of the unusual and never-heretofore-existing land of the Soviets, its strivings, aims, ideals and struggles.

To many it seems that the progressive development of the Soviet cinema has stopped. They speak of retrogression. This is, of course, wrong. And one important circumstance is underestimated by the fervent partisans of the old silent Soviet cinema, who now gaze bewilderedly as there appears Soviet film after film which in so many respects are formally similar to the occidental. If in many cases there must indeed be observed the dulling of that formal brilliance to which the occidental friends of our films had become accustomed, this is the consequence of the fact that our cinemato-graphy, in its present stage, is entirely absorbed in another sphere of investigation and deepening. A measure of hold-up in the further development of the forms and means of film expressiveness has appeared as an inevitable consequence of the diversion of investigation into another direction, a diversion recently and still obtaining: into the direction of deepening and broadening the thematic and ideological formulation of questions and problems within the content of the film. It is not accidental that precisely at this period, for the first time in our cinematography, there begin to appear the first finished images of personalities, not just of any personalities, but of the finest personalities: the leading figures of leading Communists and Bolsheviks. Just as from the revolutionary movement of the masses emerged the sole revolutionary party, that of the Bolsheviks, which heads the unconscious elements of revolution and leads them towards conscious revolutionary aims, so the film images of the leading men of our times begin during the present period to crystallise out of the general-revolutionary mass-quality of the earlier type of film. And the clarity of the Communist slogan rings more definitely, replacing the general-revolutionary slogan. The Soviet cinema is now passing through a new phase–a phase of yet more distinct Bolshevisation, a phase of yet more pointed ideological and essential militant sharpness. A phase historically logical, natural and rich in fertilising possibilities for the cinema, as most notable of arts.

This new tendency is no surprise, but a logical stage of growth, rooted in the very core of the preceding stage. Thus one who is perhaps the most devoted partisan of the mass-epical style in cinema, one whose name is forever fast-linked to the “mass”-cinema–the author of these lines–is subject to precisely this same process in his penultimate film–The Old and The New, where Marfa Lapkina appears already as an exceptional individual protagonist of the action.

The task, however, is to make this new stage sufficiently synthetic. To ensure that in its march towards new conquests of ideological depths, it not only does not lose the perfection of the achievements already attained, but advances them ever forward toward new and as yet unrealised qualities and means of expression. To raise form once more to the level of ideological content.

Being engaged at the moment on the practical solution of these problems in the new film Bezhin Meadow, only just begun, I should like to set out here a series of cursory observations on the question of the problem of form in general.

The problem of form, equally with the problem of content at the present stage, is undergoing a period of most serious deepening of principle. The lines which follow must serve to show the direction in which this problem is moving and the extent to which the new trend of thought in this sphere is closely linked in evolution to the extreme discoveries on this path made during the peak period of our silent cinema.

Let us start at the last points reached by the theoretical researches of the stage of Soviet cinema above referred to (1924-1929).

It is clear and undoubted that the ne plus ultra of those paths was the theory of the “intellectual cinema.”

This theory set before it the task of “restoring emotional fullness to the intellectual process.” This theory engrossed itself as follows, in transmuting to screen form the abstract concept, the course and halt of concepts and ideas–without intermediary. Without recourse to story, or invented plot, in fact directly–by agency of the image–composed elements shot. This theory was a broad, perhaps even a too broad, generalization of a series of possibilities of expression placed at our disposal by the methods of montage and its combinations. The theory of intellectual cinema represented, as it were, a limit, the reductio ad paradox of that hypertrophy of the montage conception with which film aesthetics were permeated during the period of blossoming of Soviet silent cinematography as a whole and my own work in particular.

Recalling the “establishment of the abstracted concept” as the framework of the possible products of the intellectual cinema, as the basic foundation of its film canvasses; and acknowledging that the movement forward of the Soviet cinema is now following other aims, namely the demonstration of such conceptual postulates by agency of concrete actions and living persons as we have noted above, let us see what can and must be the further fate of the ideas expressed at that time.

Is it then necessary to jettison all the colossal theoretical and creative material, in the turmoil of which was born the conception of the intellectual cinema? Has it proved only a curious and exciting paradox, a fata morgana of unrealized compositional possibilities? Or has its paradoxicality proved to lie not in its essence, but in the sphere of its application, so that now, after examining some of its principles, it may emerge that, in new guise, with new usage and new application, the postulates then expressed have played and may still continue to play a highly positive part in the theoretical grasping, understanding and mastering of the mysteries of the cinema?

The reader, doubtless, has already guessed that this is precisely how we incline to consider the situation, and all that follows will serve to demonstrate, perhaps only in broad outline, exactly what we understand by it, and use now as a working basis, and which, as a working hypothesis in questions of the culture of film form and composition, is fortified more and more into a complete logical conception by everyday practice.

I should like to begin with the following consideration:

It is exceedingly curious that certain theories and points of view which in a given historical epoch represent an expression of scientific knowledge, in a succeeding epoch decline as science, but continue to exist as possible and admissible not in the line of science but in the line of art and imagery.

If we take mythology, we find that at a given stage mythology is nothing else than a complex of current knowledge about phenomena, chiefly related in imagery and poetic language. All these mythological figures, which at the best we now regard as allegorical material, at some stage represented an image-compilation of knowledge of the cosmos. Later, science moved on from imagery narratives to concepts, and the store of former personified-mythological nature-symbols continued to survive as a series of scenic images, a series of literary, lyrical and other metaphors. At last they become exhausted even in this capacity and vanish into the archives. Consider even contemporary poetry, and compare it with the poetry of the eighteenth century.

Another example: take such a postulate as the a-priority of the idea, spoken of by Hegel in relation to the creation of the world. At a certain stage this was the summit of philosophical knowledge. Later, the summit was overthrown. Marx turns this postulate heels upon head in the question of the understanding of real actuality. However, if we consider our works of art, we do in fact have a condition that almost looks like the Hegelian formula, because the idea-satiation of the author, his subjection to prejudice by the idea, must determine actually the whole course of the art-work, and if every element of the art-work does not represent an embodiment of the initial idea, we shall never have as result an art-work realized to its utmost fullness. It is of course understood that the artist’s idea itself is in no way spontaneous or self-engendered, but is a socially-reflected mirror-image, a reflection of social reality. But from the moment of formation within him of the viewpoint and idea, that idea appears as determining all the actual and material structure of his creation, the whole created “world” of his creation.

Suppose we take another field– “Lavater’s physiognomy.” This in its day was regarded as an objective scientific system. But physiognomy is now no science. Lavater was already laughed at by Hegel, though Goethe, for example, still collaborated with Lavater, if anonymously. To Goethe must be assigned the authorship of, for example, a physiognomical study devoted to the head of Brutus. We do not attribute to physiognomy any objective scientific value whatsoever, but the moment we require, in course of the all-sided representation of character denoting some type, the external characterization of a countenance, we immediately start using faces in exactly the same way as Lavater did. We do so because in such a case it is important to us to create first and foremost an impression, the subjective impression of impression, the subjective impression of an observer, not the objective coordination of sign and essence actually composing character. In other words, the viewpoint that Lavater thought scientific is being “exhausted” by us in the arts, where it is needed in the line of imagery.

What is the purpose of examining all this? Analogous situations occur sometimes among the methods of the arts, and sometimes it occurs that the characteristics which represent logic in the matter of construction of form are mistaken for elements of content. Logic of this kind is, as a method, as a principle of construction fully permissible, but it becomes a nightmare if this same method, this logic of construction, is regarded simultaneously as an exhaustive content.

You will perceive already whither the matter is tending, but I wish to cite one more example, from literature. The question relates now to one of the most popular of all literary genres the detective story. What the detective story represents, of which social formations and tendencies it is the expression, this we all know. On this subject Gorki recently spoke sufficiently at the Congress of Writers. But of interest is the origin of some of the characteristics of the genre, the sources from which derives the material that has gone towards creation of the ideal vessel of the detective story form of embodiment of the given aspects of bourgeois ideology.

It appears that the detective novel counts among its forerunners, aiding it to reach full bloom at the beginning of the 19th century, Fenimore Cooper–the novelist of the North American redskins. From the ideological point of view, this type of novel, exalting the deeds of the colonizers, follows entirely the same current as the detective novel in serving as one of the most pointed forms of expression of private-property ideology. To this testified Balzac, Hugo, Eugene Sue, who produced a good deal in this literary-composition model from which later was elaborated the regular detective novel.

Recounting in their letters and diaries the inspirational images which guided them in their story constructions of chase and flight (Les Miserables, Vautrin, The Wandering Jew), they all write that the prototype that attracted them was the dark forest background of Fenimore Cooper, and that they had wished to transplant this dark forest and the action within it from the labyrinth of the virgin backwoods of America to the dark forests of the alleys and byways of Paris. The collection of clues derives from the methods of the “Pathfinders” whom this same Fenimore Cooper portrayed in his works.

Thus the image “dark forest” and the technique of the “pathfinder” from Cooper’s works serve the great romanticists such as Balzac and Hugo as a sort of initial metaphor for their intrigue of detection and adventure constructions within the maze of Paris. They contribute also to formalizing as a genre those ideological tendencies which lay at the base of the detective novel. Thus is created a whole independent type of story construction. But, parallel with this use of the “heritage” of Cooper, we see yet another sort: the type of literal transplantation. Then we have indeed ripe incongruity and nightmare. Paul Feval has written a novel in which redskins do their stuff in Paris and a scene occurs where three Indians scalp a victim in a cab!

II.

The quality of the intellectual cinema was proclaimed to be the content of the film. The trend of thoughts and the movement of thoughts were represented as the exhaustive basis of every thing that transpired in the film, i.e., a substitute for the story. Along this line–exhaustive replacement of content–it does not justify itself. And in sequel perhaps to the realization of this, the intellectual cinema has speedily grown a new conception of a theoretical kind: the intellectual cinema has acquired a little successor in the theory of the inner monologue.

The theory of the inner monologue warmed to some extent the aesthetic abstraction of the flow of concepts, by transposing the problem into the more storyish line of the portrayal of the hero’s emotions. During the discussions on the subject of the inner monologue, there was made none the less a tiny reservation, to the effect that this inner monologue could be used to construct things and not only for picturing the inner monologue. (See my article Cinema with Tears in the Magazine Close-up. S.M.E) Just a tiny little catch admitted in parentheses, but it contains the crux of the whole affair. These parentheses must be opened immediately. And herein lies the principal matter with which I wish to deal.

Which is the syntax of inner speech as opposed to that of uttered. Inner speech, the flow and sequence of thinking unformulated into the logical constructions in which uttered, formulated thought are expressed, has a special structure of its own. This structure is based on a quite distinct series of laws. What is remarkable therein, and why I am discussing it, is that the laws of construction of inner speech turn out to be precisely those laws which lie at the foundation of the whole variety of laws governing the construction of the form and composition of art-works. And there is not one formal method that does not prove the spit and image of one or another law governing the construction of inner speech, as distinct from the logic of uttered speech. Otherwise it would be without effect and void.

We know that at the basis of form creation lie sensual and image thought processes. Inner speech is precisely at the stage of image-sensual structure, not yet having attained that logical formulation with which speech clothes itself before stepping out into the open. It is noteworthy that, just as logic obeys a whole series of laws in its constructions, so, equally, this inner speech, this sensual thinking, is subject to no less clear-cut laws and structural peculiarities. These are known and, in the light of the considerations here set out, represent an inexhaustible storehouse, as it were, of laws for the construction of form, the study and analysis of which have immense importance in the task of mastering the “mysteries” of the technique of form.

For the first time we are placed in possession of a firm storehouse of postulates, bearing on what happens to the initial thesis of the theme when it is translated into a chain of sensory images. The field for study in this direction is colossal. The point is that the forms of sensual, pre-logical thinking, which are preserved in the shape of inner speech among the peoples who have reached an adequate level of social and cultural development, at the same time also represent in mankind at the dawn of cultural development norms of conduct in general, i.e., the laws according to which flow the processes of sensual thought are equivalent for them to a “habit logic” of the future. In accordance with these laws they construct norms of behavior, ceremonials, customs, speech, expressions, etc., and, if we turn to the immeasurable treasury of folklore, of out-lived and still living norms and forms of behavior preserved norms and forms of behavior preserved by communities still at the dawn of their development, we find that, what for them has been or still is a norm of behavior and custom-wisdom, turns out to be at the same time precisely what we employ as “artistic methods” and “technique of formalization” in our art-works. I have no space to discuss in detail the question of the early forms of thought process. I have no opportunity here to picture for you its basic specific characteristics, which are a reflection of the exact form of the early social organization of the communal structures. I have no time to pursue the manner in which, from these general postulates, are worked out the separate characteristic marks and forms separate characteristic marks and forms of the construction of representations. I will limit myself to quoting two or three instances exemplifying this principle, that one or other given element in the practice of form-creation is at the same time an element of custom-practice from the stage of development at which representations are still constructed in accordance with the laws of sensual thinking. I emphasize here, however, that such construction is not of course in any sense exclusive. On the contrary, from the very earliest period there obtains simultaneously a flow of practical and logical experiences, deriving from the practical labor processes; a flow that gradually increases on the basis of them, discarding these earlier forms of thinking and embracing gradually all the spheres not only of labor, but also of other intellectual activities, abandoning the earlier forms to the sphere of sensual manifestations.

Consider, for example that most popular of artistic methods, the so-called pars pro toto. The power of its effectiveness is known to everyone. The pince-nez of the surgeon in The Battleship Potemkin are firmly embedded in the memory of anyone who saw the film. The method consisted in substituting the whole (the surgeon) by a part (the pince-nez), which played his role, and, it so happened, played it much more sensual-intensively than it could have been played even by a repeated portrayal of the surgeon. It so happens that this method is the most typical example of a thinking form from the treasury of early thought processes. At that stage we were still without the unity of the whole and the part as we now understand it. At that stage of non-differentiated thinking the part is at one and the same time also the whole. There is no unity of part and whole, but instead obtains an objective identity in representation of whole and part. It is immaterial whether it be part or whole it plays invariably the role of aggregate and whole. This takes place not only in the simplest practical fields and actions, but immediately appears as soon as you emerge from the limits of the simplest “objective” practice. Thus, for example, if you receive an ornament containing a bear’s tooth, it signifies that the whole bear has been given to you, or, what in these conditions signifies the same thing, (a differentiated concept of “strength” outside the concrete specific hearer of that strength equally does not exist at this stage. S.M.E) the strength of the bear as a whole. In the conditions of actual practice such a proceeding would be absurd. No-one, having received a button off a suit, would imagine himself to be dressed in the complete suit. But as soon even as we move over into the sphere in which sensual and image constructions play the decisive role, into the sphere of artistic constructions, the same pars pro toto begins immediately to play a tremendous part for us as well. The pince-nez, taking the place of a whole surgeon, not only completely fill his role and place, but do so with a huge sensual-emotional increase in the intensity of the impression, to an extent considerably greater than could have been obtained by another portrayal of the surgeon as a whole!

As you perceive, for the purposes of a sensual artistic impression, we have used, in capacity of a compositional method, one of those laws of early thinking which, at their appropriate stages, appear as the norms and practice of everyday behavior. We made use of a construction of a sensual thinking type, and as result, instead of a “logico-informative” effect, we receive from the construction actually an emotional sensual effect. We do not register the fact that the surgeon has drowned, we emotionally react to the fact through a definite compositional presentation of this fact.

It is important to note here that what we have analyzed in respect to the use of the close-up, in our example of the surgeon’s pince-nez, is not a method characteristic only of the cinema alone and specific to it. It equally has a methodological place and is employed in, for example, literature. “Pars pro toto” in the field of literary form is what is known to us under the term synecdoche.

Let us indeed recall the definition of the two kinds of synecdoche. The first kind: this kind consists in that one receives a presentation of the part instead the part instead of the whole. This in turn has a series of sorts:

(1) Singular instead of plural.

(“The Son of Albion reaching for freedom” instead of “The sons of, etc.”)

(2) Collective instead of composition of the clan.

(“Mexico enslaved by Spain” instead of “the Mexicans enslaved.”)

(3) Part instead of whole.

(“The master’s eye.”)

(4) Definite instead of indefinite.

(“A hundred times we say.”)

The second series of synecdoches consists in the whole instead of the part. But, as you perceive, both kinds and all the sorts of subdivision are subject to one and the same basic condition. Which condition is the identity of the part and the whole and hence the “equivalence,” the equal significance in substitution of one by the other.

No less striking examples of the same occur in paintings and drawings, where two color spots and a flowing curve give a complete sensual replacement of a whole object.

What is of interest here is not this list itself, but the fact that is confirmed by the list. Namely, that we are dealing here not with specific methods, particular to this or that art-form, but first and foremost with a specific course and condition of embodied thinking sensual thinking, for which the given structure is a law. In this special, synecdoche, use of the “close-up,” in the color-spot and curve, we have but particular instances of the operation of this law of pars pro toto, characteristic of sensual thinking, dependent upon whatever art-form in which it happens to be functioning for its purpose of embodiment of the basic ideological scheme.

Let us now turn to another field. Let us take the occasion when the material of the form-creation turns out to be the artist himself. Also this confirms the truth of our postulates. Even more: in this instance the structure of the finished composition not only reproduces, as it were, a reprint of the structure of the laws along which flow sensual thought-processes. In this instance the circumstance itself, here united, of the object-subject of creation, as a whole underlies the picture of psychic state and representation corresponding to the early forms of thought. Let us look once more at two examples. All explorers and travellers are invariably peculiarly astonished at one characteristic of early forms of thought quite incomprehensible to a human being accustomed to think in the categories of current logic. It is the characteristic involving the conception that a human being, while being himself and conscious of himself as such, yet simultaneously considers himself to be also some other person or thing, and, further, to be so, just as definitely and just as concretely, materially. In the specialized literature on this subject there is the particularly popular example of one of the Indian tribes of Northern Brazil.

The Indians of this tribe–the Bororo, for example maintain that, while human beings, they are none the less at the same time also a special kind of red parrot very common in Brazil. Note that by this they do not in any way mean that they will become these birds after death, or that their ancestors were such in the remote past. Not at all. They directly maintain that they are in reality these actual birds. It is not here a matter of identity of names or relationship, they mean a complete simultaneous identity of both.

However strange and unusual this may sound to us, it is nevertheless possible to quote from artistic practice, heaps and heaps of material which would sound almost word for word like the Bororo idea concerning simultaneous double existence of two completely different and separate and, none the less, real images. It is enough only to touch on the question of the self-feeling of the actor during his creation or performance of a role. Here, immediately, arises the problem of “I” and “him.” Where “I” is the individuality of the performer, and “he” the individuality of the performed image of the role. This problem of the simultaneity of “I” and “not I” in the creation and performance of a role is one of the central “mysteries” of acting creation. The solution of it wavers between complete subordination of “him” to “I”–and “he” (complete transubstantiation). While the contemporary attitude to this problem in its formulation approaches the clear enough dialectic formula of the “unity of interpenetrating opposites,” the “I” of the actor and the “he” of the role, the leading opposite being the image, nevertheless in concrete self-feeling the matter is by a long way not always so clear and definite for the actor. In one way or another, “I” and “he,” “their” inter-relationship, “their” connections, “their” interactions inevitably figure at every stage in the working out of the role.

III.

In the course of my exposition I have had occasion to make use of the phrase “early forms of thought-process” and to illustrate my reflections by representational images current with peoples still at the dawn of culture. It has already become a traditional practice with us to be on our guard in all instances involving these fields of investigation. And not without reason: These fields are thoroughly contaminated by every kind of representative of “race science,” or even less concealed apologists of the colonial politics of imperialism. It would not be bad, therefore, here sharply to emphasize that the considerations here expressed follow a sharply different line.

Usually the construction of so-called early thought-processes is treated as form of thinking fixed in itself once and for all, characteristic of the so-called “Primitive” peoples, racially inseparable from them and not susceptible to any modification whatsoever. In this guise it serves as scientific apologia for the methods of enslavement to which such peoples are subjected by white colonizers, inasmuch as, by inference, such peoples are “after all hopeless” for culture and cultural influence.

In many ways even the celebrated Lévy-Bruhl is not exempt from this conception, although consciously he does not pursue such an aim. Along this line we quite justly attack him, since we know that forms of thinking are a reflection in consciousness of the social formations through which, at the given historical moment, this or that community collectively is passing. But in many ways, also, the opponents of Lévy-Bruhl fall into the opposite extreme, trying carefully to avoid the specificity of this independent individuality of early thought-forms. Among these, for instance, is Olivier Leroy, who, on the basis of analyzing-out a high degree of logic in the productive and technical inventiveness of the so-called “primitive” peoples, completely denies any difference between their system of thought-process and the postulates of our generally accepted logic. This is just as incorrect, and conceals beneath it an equal measure of denial of the dependence of a given system of thought from the specifics of the production relations and social postulates from which it derives.

The main error, in addition to this, is rooted in both camps in that they appreciate insufficiently the quality of gradation subsisting between the apparently incompatible systems of thought process, and completely disregard the qualitative nature of the transition from one to the other. Insufficient regard for this very circumstance frequently scares even us the moment discussion centres round the question of early thought-processes. This is the more strange in that in Engels’ Socialism-Utopian and Scientific there are actually three whole pages comprising an exhaustive examination of all the three stages of construction of thinking through which mankind passes in development. From the early diffuse-complex, part of the remarks about which we quoted above, through the formal-logical stage that negates it. And, at last, to the dialectical, absorbing “in photographic degree” the two preceding. Such an absorption of phenomena does not of course exist for the positivistic approach, of Lévy-Bruhl.

But of principal interest in all this business is the fact that not only does the process of development itself not proceed in a straight line (just like any development process), but that it marches by continual shifts back and forward, independently of whether it be progressively (the movement of backward peoples towards the higher achievements of culture under a socialist regime), or retrogressively (the regress of spiritual superstructures under the heel of national-socialism). This continual sliding from level to level, forwards and backwards, now to the higher forms of an intellectual order, now to the earlier forms of sensual thinking, occurs also at each point once reached and temporarily stable as a phase in development. Not only the content of thinking, but even its construction itself, are deeply qualitatively different for the human being of any given, socially determined type of thinking, according to this that state he may be in. The margin between the types is mobile and it suffices à not even extraordinarily sharp affective impulse to cause an extremely, it may be, logically deliberate person suddenly to react in obedience to the never dormant within him armory of sensual thinking and the norms of behavior deriving thence. When a girl to whom you have been unfaithful, tears your photo into fragments “in anger,” thus destroying the “wicked betrayer,” for a moment she reenacts the magical operation of destroying a man by the destruction of his image (based on the early identification of image and object).

(Even to the present day Mexicans in some of the remoter regions of the country in times of drought drag out from their temples the statue of the particular Catholic saint that has taken the place of the former god responsible for rains, and, on the edge of the fields, whip him for his non-activity, imagining that thereby they cause pain to him whom the statue portrays). By her momentary regression the girl returns herself, in the effect of the impulse, to that stage of development in which such an action appeared fully normal and productive of real consequences. Relatively not so very long ago, on the verge of an epoch that already knew minds such as Leonardo and Galileo, so brilliant a politician as Catherine di Medici, aided by her court magician, wished ill to her foes by transfixing with pins their miniature wax images.

In addition to this we know also not just momentary, but (temporarily!) irrevocable manifestations of precisely this same psychological retrogression, when a whole social system is in regress. Then the phenomenon is termed reaction, and the most brilliant light on the question is thrown by the flames of the national-fascist auto-da-fé of books and portraits of unwanted authors in the squares of Berlin!

One way or another, the study of this or that thinking construction locked within itself is profoundly incorrect. The quality of sliding from type of thought-process to type, from category to category, and more–the simultaneous co-presence in varying proportions of the different types and stages and the taking into account of this circumstance are equally as important, explanatory and clarifying in this as in any other sphere:

“The exact representation of the universe, of its development and the development of mankind, as equally of the reflection of this development in the mind of man, can be attained only along the path of dialectics, only by continually taking into account the general interaction between appearance and disappearance, between progressive changes and changes retrogressive…” (Engels, ibid).

The latter in our case has direct relation to those changes in the forms of sensual thinking which appear sporadically in states of effect of impulse or similar conditions, and the images constantly present in the elements of form and composition based on the laws of sensual thinking, as we have tried to demonstrate and illustrate above.

After examining into the immense material of similar phenomena, I naturally found myself confronted with a question which may excite the reader, too. This is, that art is nothing else but an artificial retrogression in the field of psychology towards the forms of earlier thought-processes, i.e., a phenomenon identical with any given form of drug, alcohol, shamanism, religion, etc.! The answer to this is simple and extremely interesting.

The dialectic of works of art is built upon a most curious “dual-unity.” The impressiveness of a work of art is built upon the fact that there takes place in it a dual process: an impetuous progressive rise along the lines of the highest intrinsic steps of consciousness and a simultaneous penetration by means of the structure of the form into the layers of profoundest sensual thinking. The polar separation of these two lines of flow creates that remarkable tension of unity of form and content characteristic of true art-works. Apart from this there are no true art-works. By predominance of one or other element the art-work becomes unfulfilled. A drive towards the thematic-logical side renders the product dry, logical, didactic. But overstress on the side of the sensual forms of thinking with insufficient account taken of thematic- logical tendency–this is equally fatal for the work: the work becomes condemned to sensual chaos, elementariness, raving. Only in the “dual-unique” interpenetration of these tendencies resides the true tension-laden unity of form and content. Herein resides the root principle difference between the highest artistic creative activity of man and, in contradistinction therefrom, all other fields wherein also occur sensual thinking or its earlier forms (infantilism, schizophrenia, religious ecstasy, hypnosis, etc.).

And if we are now on the verge of considerable successes in the field of comprehension of the universe, in the first line (to which the latest film productions bear witness), then, from the viewpoint of the technique of our craftsmanship, it stands necessary for us in every way to delve more deeply now also into the questions of the second component. These, however fleeting, notes that I have been able to set forth here serve this task. Work here is not only not finished, it has barely begun. But work here is in the extremest degree indispensable for us. The study of the corpus of material on these questions is highly important to us.

By study and absorption of this material we shall learn a very great deal about the system of laws of formal constructions and the inner laws of composition. And along the line of knowledge in the field of the system of laws of formal constructions, cinematography and indeed the arts generally are still very poor. Even at the moment we are merely probing in these fields a few bases of the systems of laws, the derivative roots of which lie in the nature itself of sensual thinking.

By analyzing along this line a whole series of questions and phenomena, we shall store up in the field of form a great corpus of exact knowledge, without which we shall never attain that general ideal of simplicity which we all have in mind. To attain this ideal and to realize this line, it is very important to guard ourselves against another line which might also begin to crop up: the line of simplificationism. This tendency is to some extent already present in the cinema, which a few already wish to expound in this way, that things should be shot simply and, in the last resort, it does not matter how. This is terrible, for we all know that the crux is not in shooting ornately and prettily (photography becomes ornate and pretty–pretty when the author knows neither what he wants to take nor how he must take what he wants).

The essence is in shooting expressively. We must travel toward the ultimate-expressive and ultimate-effective form and use the limit of simple and economic form that expresses what we need. These questions, however, can successfully be approached only by means of very serious analytical work and by means of very serious knowledge of the inward nature of artistic form. Hence we must proceed not by the path of mechanical simplification of the task, but by the path of planned analytical discovery of the secret of the nature itself of affective form.

I have sought here to show the direction in which I am now working on these questions, and I think this is the right road of investigation. If we now look back at the intellectual cinema, we shall see that the intellectual cinema did one service, in spite of its self-reductio ad absurdum when it laid claim to exhaustive style and exhaustive content.

This theory fell into the error of letting us have not a unity of form and content, but a coincidental identity of them, because in unity it is complicated to follow exactly how an effective materialization of ideas is built. But when these things became “telescoped” into “one,” then was discovered the march of inner thinking as the basic law of construction of form and composition. Now we can use the laws thus discovered already not along the line of “intellectual constructions,” but along the line of completely fulfilled constructions, both from subject and image viewpoints, since we already know some “secrets” and fundamental laws of construction of form in general.

From what I have elucidated along the lines of the past and along the lines on which I am now working, one more qualitative difference appears:

It is this, that when in our various “schools” we proclaimed the paramount importance of montage, or of the intellectual cinema, or of documentalism or some such other battle programme, it bore primarily the character of a tendency. What I am now trying briefly to expound about what I am now working on has an entirely different character. It bears a character not specifically tendencious (as futurism, expressionism or any other “programme”)–but delves into the question of the nature of things and here questions are already not concerned with the line of some given stylization, but with the line of search for a general method and mode for the problem of form, equally essential and fit for any genre of construction within our embracing style of socialist realism. The questions of tendency interest begin to grow over into a deepened interest in the whole culture itself of the field in which we work, i.e., the tendencious line here takes a turn towards the research-academic line. I have experienced this not merely creatively, but also biographically: at the moment at which I began to interest myself in these basic problems of the culture of form and the culture of cinema, I found myself in life not on production, but engaged in creation of the academy of cinematography, the road to which has been laid down by my three years’ work in the All-Union State Institute of Cinematography, and which is only now developing. Moreover, it is of interest that the phenomenon noted above is not at all isolated, this quality is not at all exclusively characteristic of our cinematography. We can perceive a whole series of theoretical and tendencious routes ceasing to exist as original “currents,” and beginning by way of transmutation and gradual change to be included into questions of methodology and science.

It is possible to point to such an example in the teaching of Marr, and the fact that his teaching, which was formerly a “japhetic” tendency in the science of languages, has now been revised from the viewpoint of Marxism and entered practice no longer as a tendency but as a generalized method in the study of languages and thinking. It is not by chance that on almost all fronts around us there are now being born academies; it is not by chance that disputes in the line of architecture are no longer a matter of rival tendencies (Corbusier or Zheltovski); discussion proceeds no longer about this question, but controversy is about the synthesis of “the three arts,” the deepening of research, the nature itself of the phenomenon of architecture.

I think that in our cinematography something very similar is now occurring. For, at the present stage, we craftsmen have no differences of principle and disputes about a whole series of programme postulates such as we had in the past. There are of course, individual shades of opinion within the comprehensive conception of the single style: Socialist Realism.

And this is in no way of sign of moribundity, as might appear to some—“unless they fight, they’re stiffs”–quite the contrary. Precisely here, and precisely in this I find the greatest and most interesting sign of the times.

I think that now, with the approach of the sixteenth year of our cinematography, we are entering a special period. These signs, to be traced today also in the parallel arts as well as being found in the cinema, are harbingers of the news that Soviet cinematography, after many periods of divergence of opinion and argument, is entering into its classical period, because the characteristics of its interests, the particular approach to its series of problems, this hunger for synthesis, this postulation of and demand for complete harmony of all the elements. from the subject matter to composition. within the frame, this demand for fullness of quality and all the features on which our cinematography has set its heart–these are the signs of highest flowering of an art.

I consider that we are now on the threshold of the most remarkable period of classicism in our cinematography, the best period in the highest sense of the word. Not to participate creatively in such a period is no longer possible. And if for the last three years I have been completely engrossed in scientific-investigatory and pedagogical work (a side of which is very briefly related above), then now I undertake simultaneously once again to embark upon production—of the film Bezhin Meadow, about which in more detail another time.

Translated by IVOR MONTAGU.

The New Theater continued Workers Theater. Workers Theater began in New York City in 1931 as the publication of The Workers Laboratory Theater collective, an agitprop group associated with Workers International Relief, becoming the League of Workers Theaters, section of the International Union of Revolutionary Theater of the Comintern. The rough production values of the first years were replaced by a color magazine as it became primarily associated with the New Theater. It contains a wealth of left cultural history and ideas. Published roughly monthly were Workers Theater from April 1931-July/Aug 1933, New Theater from Sept/Oct 1933-November 1937, New Theater and Film from April and March of 1937, (only two issues).

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n04-apr-1936-New-Theatre-UCD.pdf

PDF of issue 2: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n05-may-1936-New-Theatre.pdf

PDF of issue 3: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/workers-theatre/v3n06-jun-1936-New-Theatre.pdf