On November 13, 1909 hundreds of men and boys working in the mines of Cherry, Illinois were incinerated in a fire. J.O. Bentall, Secretary of the Illinois State Socialist Party and future Communist leader, rushed to the scene to participate in the rescue efforts. In what is a powerful, sometimes difficult to read, on-the-scene report Bentall describes the event and lays the blame squarely at the feel of Capital.

‘The Cherry Mine Murders’ by J. O. Bentall from The International Socialist Review. Vol. 10 No. 7. January, 1910.

Why Four Hundred Workers Were Burned and Suffocated in a Criminal Fire Trap.

WAS your brother one of the four hundred who perished in the Cherry coal mine November 13th? Or was it your father? Your husband? Your son?

My brother was there. My father. My son. I helped carry them out. They were cold in death. They were covered with coal dust and swollen from black damp.

I am telling you this story from what I have seen with my own eyes. Not from hearsay.

I went from Chicago right to Cherry. With thousands of others I stood and looked from the outside. Then I broke through the line and joined the volunteer rescuers. I put on overalls, jacket, cap and lamp and went down into the tomb that contained over four hundred victims—a few living, most of them dead.

I helped plug the entries to prevent the fire from spreading. I had a hand in timbering where the roof was loose, or where collars were breaking. I cut legs off the dead mules so we could get them through the passageways and clear the track for bringing out the men. I was with the gang that found nineteen dead in one pile and twenty-one in another, thirty-seven in a third and one hundred and sixty-two in a fourth.

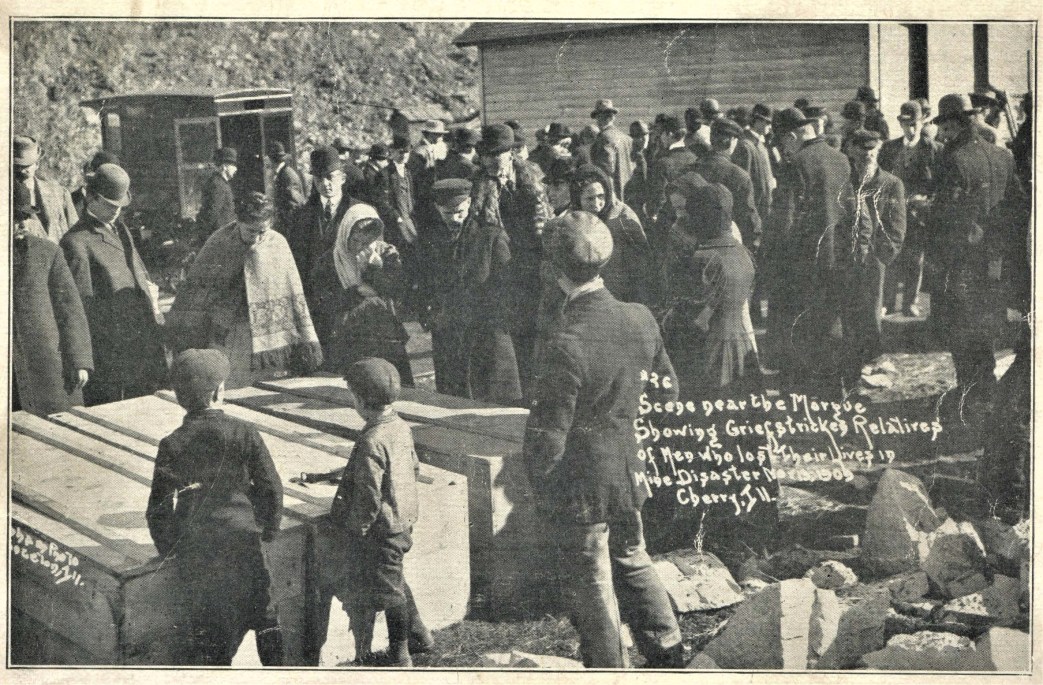

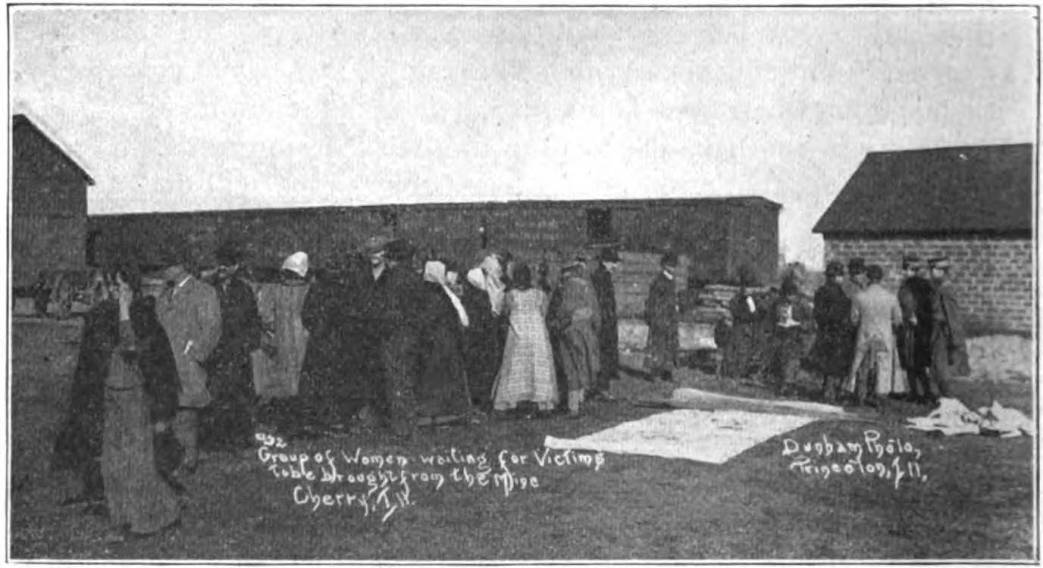

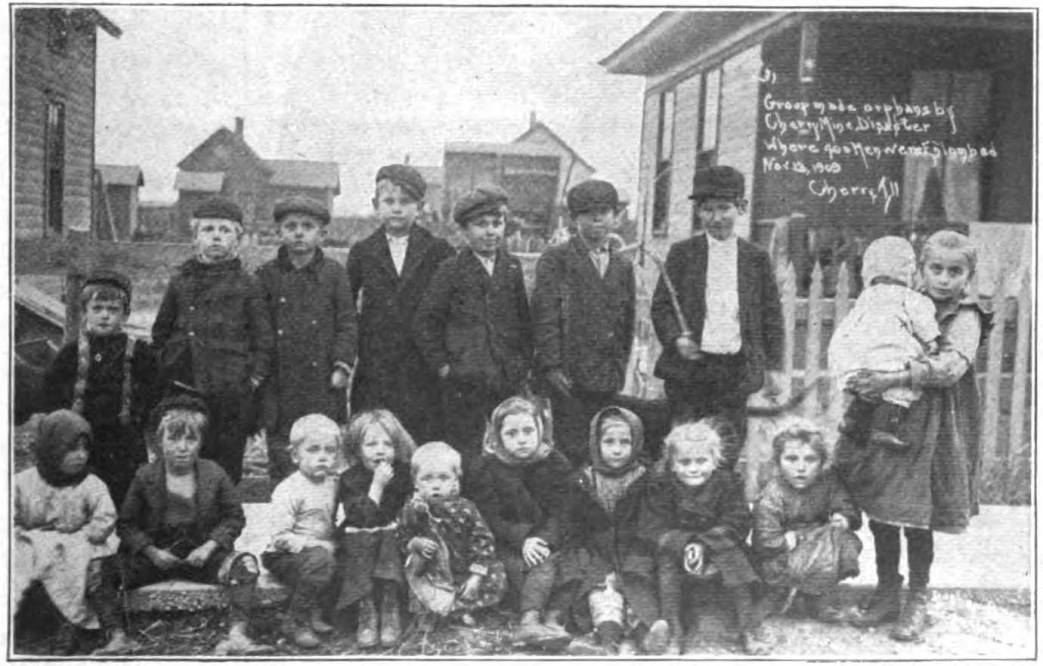

We took those men—our brothers—and loaded them into the cars-eight or ten of them into each car. We pushed them a mile, a mile and a half, through the tunnels to the shaft and brought them up. We laid them on canvas in rows on the ground—in rows eighty, a hundred feet long. We carried them on stretchers, made of scantlings and coarse canvas, into the morgue. We put them into pine coffins—cheap boxes—furnished by the company. We brushed away a tear occasionally as the body of our brother was hauled off to the long trench—the ditch—dug for him and the others, for the old man whose gray hair was black with coal, for the little pale boy whose mother stood shivering on the edge of the collective tomb.

You already know how the company failed to repair the electric lighting. How unprotected torches were put up along the tracks where coal and hay was pushed. How the bales brushed the torches and caught fire. How little boys under legal age were made to do this work that grown men should have done. How these little fellows became frightened when the hay caught fire and how they were left without aid in their death-trap. How they had to run around empty-handed, not a bucket or barrel of water being provided in the entire mine.

All this you have heard and doubted. I found that every bit of it was true.

I found more.

Jennie Miller told me that as soon as she heard that something was wrong at the mine she hastened to the shaft. For two hours after the fire was started, while coal was being hoisted, she stood there waiting for her husband to come up. But he didn’t. The coal cars came. Her husband came up ten days later and I helped carry him to the morgue.

The men who heard about the fire wanted to go up at once but were told by the company’s boss to “get back to work, you cowards.” There was coal to be hauled up and the men could wait. They waited. Two hundred of them are still waiting. Nearly two hundred others are waiting in the trench in the company’s pine boxes.

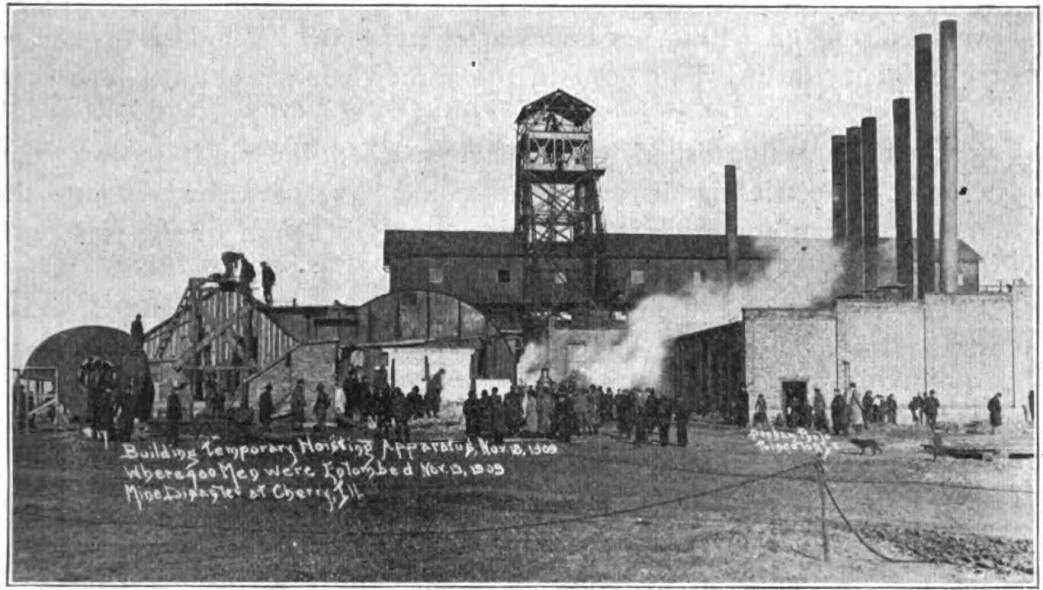

The fire spread and became intense. The fan was sucking the air up, and the air shaft, built of brittle wood instead of being constructed of iron and steel as the law prescribes, was soon threatened. To avoid loss of a few boards in the air shaft the fan was reversed, throwing the wind, and with it the fire, up the main shaft.

The two shafts were now successfully closed to all living beings. Other exits there were none. That the law requires escapes for the workers was treated as an absurdity by the company.

To dig holes in the ground for the safety of the miners is to dig holes into the dividends of the company. Neither of them were dug. To make provisions for the workers’ reasonable security is not the concern of the company.

No! No! It does not pay to make things safe for the workers.

Then, to stop the fire the mine had to be sealed. Everybody knew that this also sealed the fate of the entombed men. But the coal was burning and that must not be allowed.

The unfortunates in the dark channels knew what that meant. They hastened to remote parts of the mine. They knew that black damp, the miners’ deathly dread, was following them. They built walls and tamped the cracks to shut out their deadly enemy. They killed the mules so they would not consume the limited supply of oxygen in the prison of these men. Then they waited. They had faith in the men on top and in their comrades who knew their fate.

But the company stood in the way. The comrades above pleaded and implored. But the iron soul of the company refused to yield.

The consensus of opinion among the miners is that the fire could have been put out within ten hours after it started. Suppose that a son of President Earling had been in the mine, would not this have been done?

Chemical extinguishers could have reached the shaft in less than one hour. Electric signals and lights could have been lowered into the mine to tell that some effort was being made in behalf of the prisoners. Put nothing was done.

The men in the tomb waited and waited. Sunday and Monday passed. No sign of help. Tuesday and Wednesday came and went, all of them twenty-four hours each. The water was gone. The oil was used up. Hunger and thirst became unendurable. The mules had been dead several days. Their flesh, raw and putrid, was not inviting, but it tasted good. In the meanwhile the officials dined sumptuously in the palace cars.

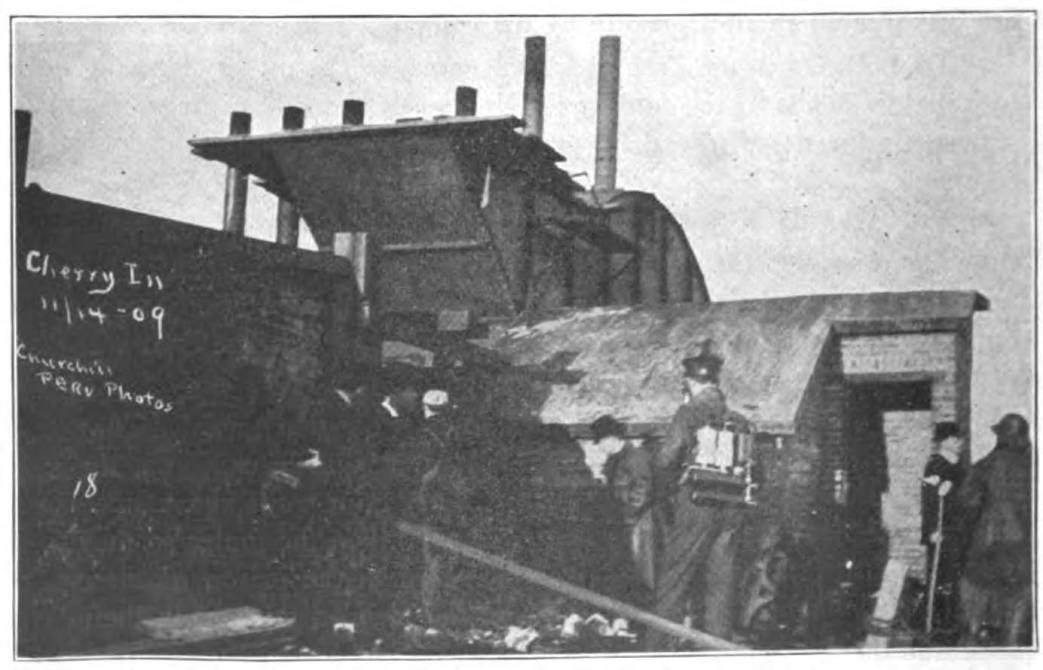

Thursday and Friday saw the mine open and rescuers descend. Headed by pompous state and company officials it was difficult for the practical miners to do much. We pleaded with the officials to be allowed to go into this entry and that, to be allowed to investigate the possible retreats where men might be alive, but we were always told to stick right to the “inspectors.”

We had passed those entries for three days. Several of them were known to contain workers, but what could we do? The hunger and thirst of the men in these dungeons drove them into a frenzy. They agreed that even if opening the door would mean swift death from black damp there was no use in waiting any longer. So one of them broke through. This was on Saturday. He saw what he could have seen three days before—the lights in the caps of the rescuers.

A cry went up to his fellows. Some came crawling out. Most of them were too weak to walk and had to be carried. One died when he reached the top. Twenty are still alive.

The company took them into custody to shape their testimony as much as possible and to scold them for having killed the mules. The wives and children were not allowed to see them for some time except through the windows of the cars.

The rescue work still dragged. On Sunday, a week after the fire, we went down again. But the inspectors held us back all the time. We fixed the entry where some smoke was coming out. While in the process of doing this “Inspector” Dunlop wanted a hole plugged. I had cut a sand bag open with an ax, thus tearing the sack instead of carefully untieing the string. This ragged sack was known to be in the pile somewhere and Dunlop told us to hunt for it.

“Here is another sack to plug the hole,” I suggested.

“Damn it; that’s too good. The broken sack will do,” answered Dunlop.

I took on a humble look and agreed with him that it was wasteful to take a new sack to stop up a hole with and as we could not find the torn one, I obeyed his stern command to “plug it with clay.”

But Dunlop did not know who I was or he would not have tried so hard to save four cents for the company.

When we were through plugging this entry, which was done in a short time, we proceeded to explore other places where men, living or dead, might be found.

We met “Inspector” Taylor, who also was in command. Taylor and Dunlop fell into a discussion and did not agree. It was this and it was that. The whole procedure was clearly made up. I got into a bunch of fellows who wanted to do something. We stole away and fell upon a heap of some twenty bodies. We took three of them to the shaft and went up. By that time there were some twenty thousand people at the mine bending the ropes and craning their necks to see the product of the rescuers’ work.

It was not pleasing to the company to have any more bodies brought up that day and we were “gently” told not to leave the “inspectors” any more, and we didn’t.

During the middle of the afternoon of this same Sunday—the second after the fire—about forty of us were down to help out. Among them were Duncan McDonald and Bill James, union officials. We were all ready to do something, but were told to sit down and wait until the “inspector” and one of the men go off to see if everything was safe. We waited for three hours and became alarmed, thinking; the advance explorers might have been overcome by black damp. We sent two fellows to investigate. The “inspector” became quite indignant, and our committee was told to go back and mind its orders.

In this way all Sunday was spent. The people on top were under the impression that the rescuers below were busy. The widows were sure that their husbands would soon be brought forth.

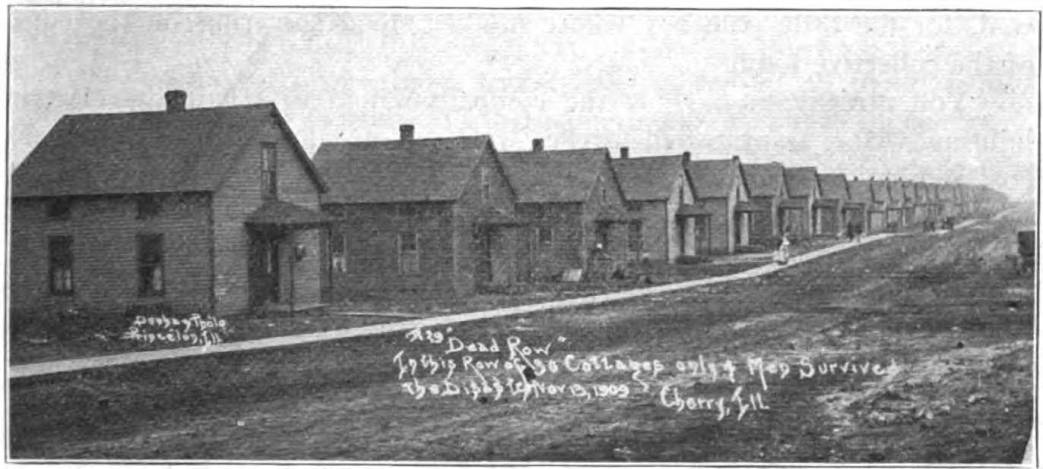

Little Albert Buckle, 15 years old November 28, who escaped on the last car up, and his mother and sister stood at the ropes all day watching for “Rich,” who was 16 years the 21st of last June, and who had worked in the mine ever since his father was killed three years ago, but poor Richard was not brought up that day. On Monday I went to see the broken-hearted mother but I could not comfort her.

At one time we were told by “Inspector” Taylor that real work was to be done. Twenty of us were at the bottom of the mine ready to take orders and go ahead.

Taylor laid fine plans. “I will put five or six of you in charge of Mr. Jones. Another company will go with Mr. Smith. Two or three will go with me. The rest will be stationed as follows.”

A fine plan was outlined. We felt good. Everybody was ready and it actually seemed as if we were to accomplish something. But all at once, after this elaborate schedule which had consumed over an hour, “Inspector” Taylor turned to us very pleasantly, saying:

“Now, gentlemen, you have been down here quite a while and it would be well for you all to go up to get a lunch. Then we will carry on the work we have outlined.”

Of course there was nothing to do but to go up and get a lunch. It is needless to say that Taylor never got back to the boys to execute the plan.

But we went up to lunch. Yes, for ten days we had gone up to lunch every six or eight hours. It was hard work to wander around in the mine. We needed fresh air and material to make blood and muscle out of.

The lunch room was in the company’s boiler room. There were two pieces of flooring sixteen feet long on some old boxes wiggling on a pile of gas pipes and iron carelessly scattered from the repair corner. Facing us as we sat down was a “table” made up of three pieces of flooring on two empty salt barrels. At the end of the table was a dirty gasoline stove on top of which was a precarious-looking wash boiler with coffee.

On the “table” were two dozen tin cups, a paper box with sugar, a tray of ham sandwiches and two spoons. Three “visiting nurses” were between us and the table who handed sandwiches and coffee to the volunteer rescuers. One nurse at each end of the line would start to stir the coffee for the men and when they met in the middle with the two spoons held high in the air they would call out:

“Are you all stirred?”

“Yes, we are all stirred,” I told them, “mightily stirred. Have they only two spoons over in the Pullman cars also?”

“Oh, there are lots of spoons over there, but they are for the officials,” was the reply.

After twelve days the best the company could do was to furnish the volunteers with sandwiches, coffee and two spoons. This was our food. They also furnished lodging.

Yes, in the night when we were too tired to go down another trip we tried to find a spot to rest. The firemen had been made to “double up” in the Pullmans, but the berths thus made available were for sale at such a figure as to make it impossible for the volunteers to sleep in these comfortable bunks.

So we just found some old paper and spread it on the brick-paved floor of the boiler room, selected a chunk of coal on which we also placed a piece of paper and used it for a pillow.

And we were fairly comfortable—more so than the men in the mine, who were walled in to keep from the black damp and who were suffering the agony of death-like suspense waiting for their rescuers, that were held back by the iron souls of the company’s officials.

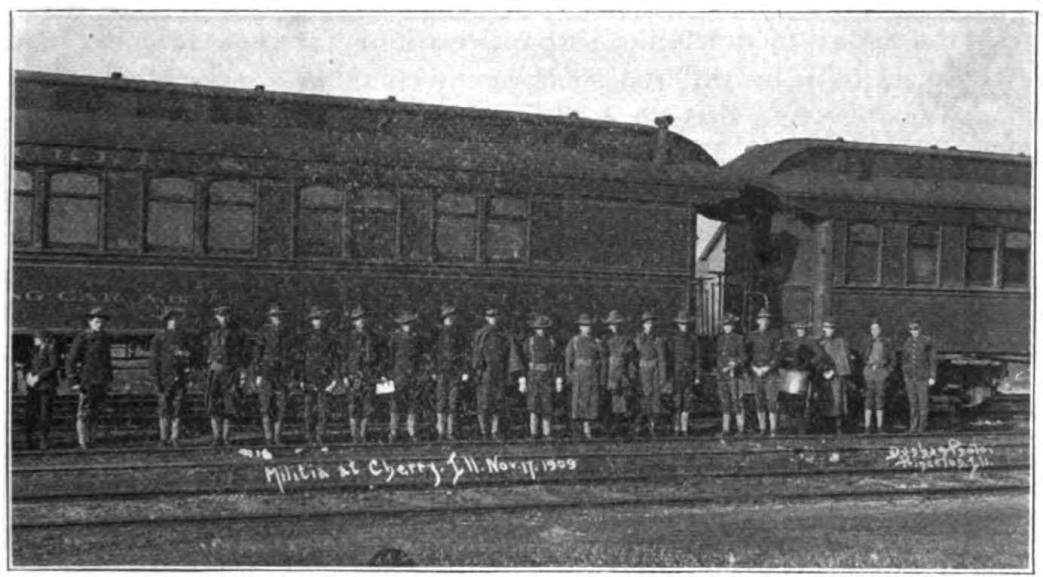

We were told that the Red Cross Society was taking care of the hungry in Cherry. Thousands of dollars have been given to this fake society, of which W. H. Taft, President of the United States, is president. This society can be forgiven for its total neglect of the rescuers. The society for prohibiting cruelty to animals would, however, have declared it outrageous to feed men on only one kind of food for a long time, especially when they are working as the volunteers were. “The Red Cross” could not see this fearful wrong. Nor could this Red Cross—rather Red Graft, this bloody hypocrite of the capitalist hydra—discover any need among the people bereft of husbands and brothers, starving in their hovels. I went around to a great number of homes and asked how their needs were supplied. Most of them had been helped by kind neighbors, none by the Red Cross. The only beneficiaries of the Red Cross seemed to be the soldiers and the nurses, who were having a high time flirting and carousing, while the hungry women and children in Cherry were the least possible concern to the Red Graft.

Had it not been for the neighbors and some farmers, as well as the little Congregational church, whose basement was given over to the charity workers, the women and children of the murdered miners would have suffered from starvation even the first and second week. I brought this criminal neglect on the part of the Red Cross Society to the notice of several prominent people, but my story was not believed. I pointed out how the Red Cross had utterly failed to pay any attention to the awful distress of the bereaved, but everybody had faith in this national organization in spite of the fumblings it has been guilty of from the catastrophe in San Francisco to the Cherry holocaust.

Now, after a month of suffering, when the wail and cry of the cold and hungry can no longer be smothered, the daily papers are compelled to show up the real situation.

But in spite of these facts, Graham Taylor, D. D., a minister and professor in the Chicago Theological Seminary, member of the Illinois Mining Investigating Committee, writes an article in “The Survey,” lauding the Red Cross, the “inspectors” and company, bluffing the people into the belief that the hundreds of thousands of dollars given to the Red Cross are judiciously spent, when he knows or ought to know that scarcely a drippling has actually gone to the real sufferers.

And just now Alderman Scully, of Chicago, who has been to Cherry and seen the situation, demands that the public funds given to the Red Cross be turned over to the Miners’ Union, as the Red Cross has proven itself wholly incapable, having placed its orders in the hands of unscrupulous merchants who charge 25 cents a pound for the poorest kind of meat and in every other way demand exorbitant prices, leaving people in utmost destitution.

This Red Cross Society is what Graham Taylor calls “an experienced agency which commanded the confidence of the local and outside communities.”

One little farmer woman, Mrs. Anna N. Kendall, living a few miles from Cherry, did more all alone in providing needed clothing for the babies, that were being born while their fathers were carried out of the black pit, and for two hundred other little ones yet to be born into the world fatherless, than all the Red Cross Society with its large retinue of officers and salaried relief experts has done during the entire period of distress in Cherry. She is the real charity heroine in the Cherry disaster.

Had the miners’ union been in shape to take hold—to demand possession of the situation—from the start the workers could have been brought out alive with very few exceptions, and the immediate wants of those who had lost their bread winners could have been filled systematically and efficiently.

But this wholesale murder of workers, with the subsequent outrages on the patience and long suffering of their relatives and the people in general, with the spiriting away of witnesses and the frustration of justice, forces upon the toilers a new reason why we should unite and take into our own hands the industries of the world and put within reach the elements necessary to the life and progress of the whole human race.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v10n07-jan-1910-ISR-gog-LB-cov.pdf