Ewald Koettggen, veteran New Jersey silk worker and leading I.W.W. organizer, traces the production of silk from the cocoon in Japan to the dye-house in Paterson.

‘Making Silk’ by Ewald Koettgen from International Socialist Review. Vol. 14 No. 9. March, 1914.

THE silk industry was considered, at one time, a luxury producer, only. Through the tremendous development in recent years it has been possible to use silk in the manufacture of so great a variety of articles that we can hardly consider it an industry of luxuries today.

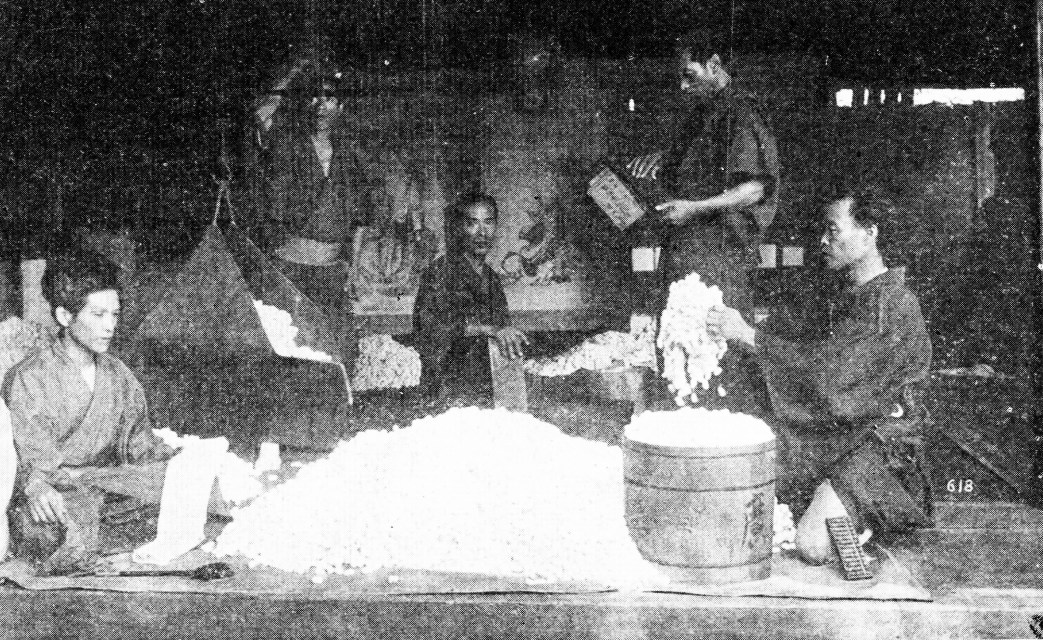

The process through which silk passes before it is put on the market is very interesting, and the thousands of people who handle silk fabric have not the faintest idea how it is produced. Raw silk is raised chiefly in Japan, China, Turkey, Italy and Syria. The best qualities used in the United States come from Japan. Silk worms are raised systematically in large numbers. They have the appearance of caterpillars and are a voracious crowd. They gorge themselves on the leaves of the mulberry trees during their short lives. When they become cocoons they are from one to two inches in length and are white in color. In Turkey some reach the length of three inches. The cocoons are covered with tiny silk threads, and after they have been gathered they are sorted out according to their value. If they have developed too far towards the butterfly stage the silk is spoiled and these are used as stock for the next crop.

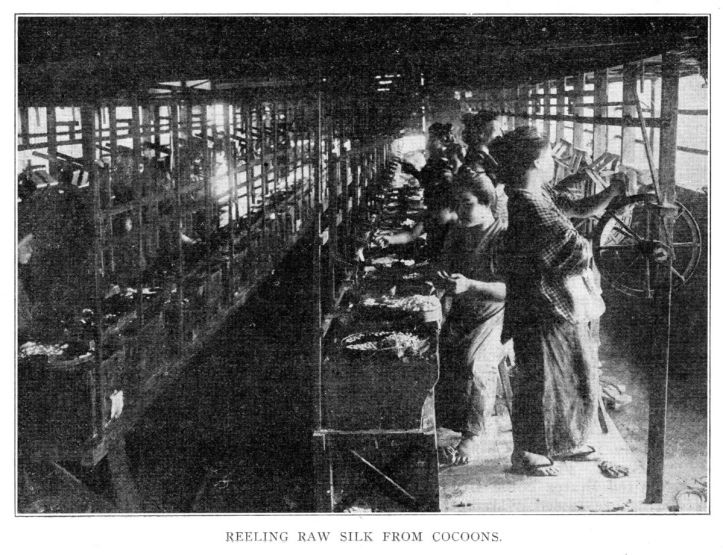

After sorting the cocoons they are subjected to an intense heat in order to kill the larva inside of them. With the aid of hot water the frail, thin threads are unraveled from the cocoons and wound into skeins. The silk in this state is full of gum from the cocoons and when next it goes into throwing plants, the skeins have to be soaked in hot water over night before they can be handled. The large amount of gum stiffens the silk when it is dry.

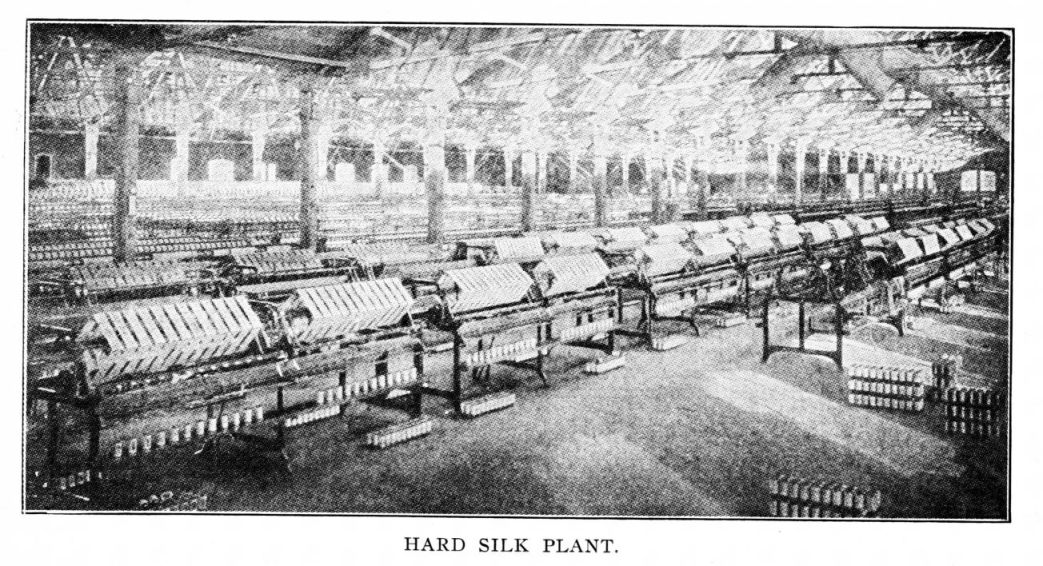

The silk thread is then wound upon bobbins and the rooms where this is done are always full of steam to prevent the silk from becoming dry and stiff. Next the thread goes to the doublers, where two or three of the tiny threads are twisted into one in order to make them strong enough to be woven into cloth. The cheaper and plain color grades of silks are woven from the raw silk and the pieces are dyed after they are woven, but the better grades and mixed color are woven from silk that has been dyed in the thread.

When the silk is to be dyed in the thread it goes to the dye-houses after it has been doubled and there is where the adulteration occurs. Of this more will be said later. From the dye-houses it goes into the silk mill and the winders wind it again from the skeins onto bobbins. Then the warpers make the warps from the bobbins and the weavers weave the warps into cloth.

Machines have been introduced into all branches of the industry and have displaced the old form of hand production. When the silk industry was in its primitive form it was carried on in the homes of the workers. The hand loom weavers of thirty or more years ago were their own masters. They owned their own looms and were highly skilled mechanics. The work was hard and other, members of the family had to assist in the labor. The weavers of old were compelled to do all the preliminary work. They had to make the warp, enter it through the harness and reed. If it happened to be jacquard work they had to build their own harness and cut the cards for the machine. The wife or children of the silk weaver had to do the quill-winding, when he did not do it himself. The motive power was supplied by the hands and feet of the weaver.

It required great physical exertion to turn a ribbon loom for ten or twelve hour and the wife of a ribbon weaver was often obliged to help turn it in order to make it possible for the weaver to endure.

While the old hand-loom weaver was his own master and comparatively free, the whole family had to work very hard and produced comparatively few yards of silk per day. The silk had to be of very good quality to stand the strain of the hand loom. It was unadulterated and was dyed in the standard colors only. A piece of silk cloth woven on the hand loom would not fall to pieces in a few months like the silk of today. It would last for many years.

When the hand-loom weaver was forced from the home and the hand-loom into the mill and became the power-loom the labor dividing process began at once. The weaver did nothing but weave at the loom. Other workers did the winding, the warping, the quill winding, the entering of warps through the harness and reed, while others twisted on the warps, or built the harness, cut the cards or fixed the looms, and so on.

After a while the weavers were given two looms to operate instead of one. Then the looms were made large enough to hold cloth of a double width, and today we find weavers operating four looms, and in some cases six. The greed of the silk mill owners has turned all the inventions and improvements in machinery to the benefit of themselves. To give an idea of what has taken place I might cite an example of a personal experience.

Fifteen years ago the writer was operating two looms, each loom containing 18 inches of cloth (a hand loom weaver operated only one loom of this kind), 60 reed, 3 threads in a dent, 90 picks to an inch, taffate weave, and was paid 10 cents per yard. Now a weaver is compelled to run four looms, 36 inches of cloth in each loom, 60 reed, 2 en3s in a dent, 64 picks to an inch, and are paid 2 1/2 cents per yard. Six years ago messaline jobs were paid as follows: A weaver would run two looms, goods 36 inches wide, 64 reed, 3 threads, 5 shafts, 104 picks per inch, \\l/2 cents per yard. Now a weaver operates four looms on the same kind of work and receives 5 cents per yard. At two looms a weaver could make 15 yards per loom per day, or 30 yards per day on two looms. This makes $3.45 for 30 yards. On 4 looms a weaver can make about 12 yards per loom per day, or 48 yards per day. Forty-eight yards at 5 cents per yard makes $2.40. In other words, a weaver produces 18 yards more per day and is paid $1.05 less than before. It must be taken into consideration that there is no improvement on the looms. They are exactly the same as they were when they were running two instead of four.

The ribbon weavers have fared just as bad. The weaver of 1913 produced more than three times as much ribbon and was paid less than in 1894.

The 25 foot double deck ribbon loom is common today, while in 1894 the looms were half as long and single deck, or circular batton, as the weavers call them. It must be taken into consideration that the silk furnished is not as good as the silk supplied the hand loom weaver or the early power loom weaver. The mill owners, seeking always larger and larger profits, have resorted to adulteration of silk and are “sabotaging” the silk-buying public just as much as the woolen manufacturers who sell goods for “all wool” which is half shoddy.

Tin Silk.

The adulteration of the silk is done in the dyeing process, and is known as weighting. In order to make the readers understand the reasons for the weighting of silk it is necessary to explain. A piece of thin flimsy silk cloth contains not many threads of silk. If a heavier and more substantial piece of cloth is desired more silk threads must be used in its manufacture. The thinner the individual silk thread is, the more threads are required to make a substantial piece of silk cloth. Mixing other non-silk threads with the silk is an ordinary trick of the trade. Cotton threads are often mixed with the silk and woven into the cloth. But cotton will not deceive nor be concealed and the buyers want silk only. To thicken the individual silk thread and use less silk threads in a piece of cloth is the problem.

To swell the threads, the raw silk is put through a process known as dynamiting. In this process the silk is put through a solution of tin, red iron and muriatic acid. This solution, in conjunction with the dye, sticks to the silk and makes the individual silk threads thicker. Less threads are required to make a substantial looking piece of cloth. But the acid soon eats its way into the delicate silk fibre and makes the cloth woven from such silk rot in a short time. To give the reader an idea to what extent this weighting of silk is carried on I will quote from the price list of one of the largest silk dyeing concerns in the country, the Weidman Silk Dyeing Company, located at Paterson, N.J.

In colors: Tin weighted, brights and souples, one pound of raw silk is weighted up to 32 ounces. Tin weighted twist to 38 ounces. Umbrella dyes, brights and souples to 30 ounces. Tailoring and hat-band dyes to 24 ounces.

In blacks: Brights are weighted up to 44 ounces. Spun and schappe to 40 ounces. Spun and silk twist to 50 ounces.

Souple to 60 ounces.

It should be stated here that the raw silk is put through a process known as stripping before it is dyed, or weighted. This is done in order to remove the gum from the silk, and every pound of silk loses from 2 to 4 ounces in weight. So that when a pound is weighted up to 60 ounces there is only 12 ounces of real silk. When the “dear public” buys 60 ounces of the last named kind of “silk” they buy in reality 48 ounces of old tin and iron. No sabotage there! Those who do piece work, when using this kind of adulterated silk, must work so much harder, because the acid rots the silk and the threads break continually.

Inventions on looms are often nullified by adulterated silk. For instance: There is a contrivance in brood silk looms which will stop the loom automatically when the thread breaks. This would be an advantage to the weaver, but is not generally used because it requires good silk. The rotten filling furnished the weavers will not stand sufficient tension to operate the stopping apparatus, and in consequence the weavers are compelled to run box-looms with from 2 to 7 shuttles with as many different colors of filling without this stopping apparatus, and what this means only a weaver can understand who has tried it.

The production of silk was at one time a man’s industry, but it is rapidly becoming an industry of women and children. The number of women and children employed in the silk mills at the present time is at least 80 per cent. In the hardsilk plants women and children are employed exclusively. All the winding, quill-winding, blocking and picking is done by women and children. Most of the warping, three-fourths of the weaving, is also done by women, and now women are entering the dyehouses. Dyeing is the most unsanitary work in the mills. The rooms are constantly filled with steam and the floors are covered with water. The dyers are compelled to work with their hands in strong acids, and must wear wooden shoes weighing about 5 pounds each in order to keep their feet dry. They are subject to rheumatism and colds. The children receive as low as $2.50 a week in the hard-silk, or throwing plants. The quillwinders, winders, blockers and pickers average about $4.50 or $5.00 per week.

The “labor laws” on the statute books of the various states are dead letters as far as the workers are concerned. Whenever Mr. Boss has plenty of orders they work overtime. Women and children often work twelve hours or more. In some cases a night shift is put on and it works twelve hours per night. The factory inspector usually gets no further than the office. It is useless to appeal to him. The state of New Jersey has a 55-hour labor law. According to this law neither women nor minors shall be employed in any mill or factory in the state for more than 55 hours per week. Some time ago a mill in Paterson, N.J., was working 70 hours per week. This mill employed women and minors only. The factory inspector was notified that this mill was violating the law. After “investigating” a couple of weeks he replied: That by “mutual agreement” between employers and employees the law permits the latter to work more than 55 hours per Week. The mutual agreement consisted in the boss putting up the notice that the mill would run overtime until further notice. The workers, being unorganized, had to quit their jobs as individuals or work 70 hours. To work meant that they acquiesced in this “mutual agreement.” And still we are told that we need more “labor laws.”

The teaching of the I.W.W. that the laws of the mills and factories are made either in the office of the boss or in the hall of the union has taken strong root among thousands of silk workers. Since the big silk workers’ strike of last summer the silk workers have come to realize that the old form of craft unionism of the American Federation of Labor with their divisions and their lobbying committees in the legislatures can never benefit the working class. They realize that all workers engaged in a silk mill should belong to the same union, from the engineer and fireman down to the boy who sweeps the floor; that all the workers from all the silk mills in any locality should belong to the same local union under the, same charter, and that the workers working in the mills must make the laws for the mills where they work and enforce them themselves, on the job. It is the mission of the revolutionary industrial organization, the Industrial Workers of the World, to drill the workers to control all conditions of labor in factory and mill as well as all products of labor. The workers must have complete control over industry. When this has been accomplished in the most important industries, the workers, through their economic organization, will be able to operate the industries for their own benefit, abolish the wages system, and establish the Democracy of Labor. The industrial union will take the place of the capitalist state.

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v14n09-mar-1914-ISR-riaz-ocr.pdf