A leader of the Comintern’s ‘Near Eastern Department’ with a valuable history of the emergence of the modern working class in Turkey; from the end of the Ottomans to the first years of Kemalist capitalism, including early Communist organizing.

‘The Labour Movement in Turkey’ by P. Kataigorodsky from Communist International. Vol. 2 No. 17. October, 1925.

THE first steam engine appeared in Turkey in 1860. However, the results of this “industrial revolution,” if we may so term it, only began to make themselves felt in the ’80’s. Handicraft industry, with its apprenticeship and hierarchy, only began to be seriously shaken towards the end of the ’80’s. The old handicraft corporations began to break up. The working class appears on the scene. In 1893 we observe the first attempts towards trade union organisation of the workers employed in the “Tofan” gun factory. The workers of this factory formed an “Association of Ottoman Mechanics.”

However, this organisation faded away, not having had time to flourish. Abdul Hamid generally would not put up with free organisations, workers least of all. He systematically persecuted and exiled the leaders and organisers of unions of this kind. The relentless regime of the bloody Sultan cruelly suppressed the young flights of workers’ organisations. The industrial workers of Turkey were scattered and lived in partial obscurity of ignorance and stagnation. Only the Young Turk coup d’etat of 1908 gave a strong stimulus to the development of workers’ organisations. The proclamation of a constitution in Turkey shook up Turkish society and covered the whole country with innumerable organisations. This organisational fever also affected the Turkish working class, which at that time numbered 100,000 workers employed in factories, railways, etc.

This movement of the Turkish workers was organised by Bulgarian, Armenian, Jewish and other Socialists upon whom the “Committee of Unity and Progress” vented all its wrath and all the strength of State power. The first to organise were the workers on the Oriental Railway and the workers and employees of the Constantinople tram depot. In 1909 Turkey experienced the first strike of railwaymen and tramwaymen.

The Young Turk Government became frightened at this red spectre of the workers’ movement and published a stern law on strikes, which remains in force to this very day. According to this law the workers have the right to declare a strike only after the Governmental Commissar finds the demands of the workers worthy of consideration and only on condition that the government official is unable to reconcile both sides. The workers have only the right to declare a strike two months after the examination of the questions in dispute. This penal law practically amounted to a complete prohibition of the strike movement.

With regard to the question of workers’ associations, the Young Turks did not issue a special law regulating such organisations, but the workers utilised the general law on associations for forming their corporations, which subsequently received the name of “Dernek.”

The law on associations, which existed during the Young Turk regime, allowed of the formation of branches in the provinces also, but strictly prohibited the formation of a federation of unions, which in practice deprived the workers of the possibility of uniting legally.

During the imperialist war the “Union and Progress Party” assisted the process of the formation of a national bourgeoisie by setting up a national industry, forming limited companies and banks, while the same Party ruling at that time organised the petty bourgeoisie and port workers. The Committee of Union and Progress organised textile workers, bakers, bootmakers (both skilled and semi-skilled tradesmen), and others into productive co-operative societies (artels). These artels received orders from the Government and also credit and machines which the Government ordered from Germany. The workers in these productive societies were exempt from military duty as they worked “for defence.” At the same time the government set up an extensive network of consumers’ co-operatives, which were supplied with goods from the stores of large monopolist limited companies.

In this manner the Young Turks laid their hands on all the newly-formed organisations, which remained under the double guardianship of the Government officials.

After the Mudros amnesty of 1918, which brought a complete defeat to the Young Turkish regime, the workers of Constantinople fell under the influence of the British and French occupiers who competed between one another. Various adventurers came on the scene who tried to form workers’ organisations in order to sell them to the British or the French. Among the latter kind of adventurers the energetic figure of the workers’ apostate, Hilmi Bey, corrupted by the British, stands out in bold relief. He was able to group around himself 7,000 workers of Constantinople in 1921 and lead the strike of tramway workers which ended successfully. (The Constantinople tramways belong to a Franco-Belgian company.) But in February, 1922, the French got the best of the British and with the aid of Turkish officials they succeeded in forming a “Society for the Defence of the Workers,” exclusively of Mussulman workers. Hilmi left the scene and another swindler, Shakir Rassim, stood at the head of the Constantinople workers’ organisation. He represented the Constantinople workers at Amsterdam in 1922.

However, this adventurer did not “get away with it.” The strike of the tramway workers in 1922 ended in failure. The “Society for the Defence of the Workers” fell to pieces, leaving behind it dirty traces of nationalistic prejudices, which had been energetically cultivated by the corrupt leader, Shakir Rassim. It suffices to point out that it was exclusively Mussulman workers who were accepted into the “Society,” that the members of this “Society” performed religious rites such as sacrificing rams at various festivals, which became the clear physiognomy of such a “Labour” organisation.

During this time, the Labour movement in Anatolia was entirely under the influence of the Kemalists. The most important group of the Anatolian working class were the railwaymen, workers in the ammunition factories and miners. Although the workers in Government enterprises were deprived of the right to form unions, the Kemalist Government did not hinder the formation of mutual aid societies and organisation of the workers in connection therewith. In addition, the Government, being interested in the normal functioning of the above-mentioned enterprises, paid high wages particularly to the railwaymen and workers in munition factories (three Turkish lira per day), which guaranteed and ensured them in advance from strikes and disturbance on the part of the workers. The eight-hour day was introduced for the miners, which included the time of descent and ascent. The petty bourgeois Socialist Mahmud Essad, who was at the head of the Commissariat for National Economy, prepared a project for legislation on workers’ insurance, the granting of free medical aid and free education for workers’ children, etc.

The Kemalists allowed the workers to form mutual aid funds, but their Liberalism did not go so far as to recognize the workers’ right of free coalition and conclusion of collective agreements.

The Labour Movement of Turkey after the Victory of the National Revolution.

There are altogether about 200,000 urban workers in Turkey. They are distributed in the following manner according to the branch of production:

Railwaymen: 8,200 (about 5,000 organised in unions). Miners: 25,000 (8,000 organised).

Factory workers: 40,000 (12,000 organised).

Builders: 12,000 (4,000 organised).

Tramwaymen: 3,000 (1,500 organised).

Seamen: 5,000 (2,000 organised).

Dockers: 7,000 (all organised in craft unions).

Chauffeurs and Cabmen: 10,000 (5,000 in craft unions). Tobacco workers: 25,000 (7,000 organised).

Seasonal workers: 15,000 (totally unorganised).

Printers: 1,500 (1,000 organised).

Lightermen: 20,000 (10,000 organised).

It stands to reason that these figures are not absolutely accurate, as there are not any statistics in Turkey for the time of the war. Therefore, one has to believe in the statistics given either by the bulletins of the Commissariat of National Economy, or by the journal “L’Economiste d’Orient” or else in reports of Turkish Communists, etc.

Such, however, are the rough figures of the numerical composition of the urban workers, not counting the shop assistants (of whom there are some tens of thousands in Constantinople alone) and the State and Municipal employees (about 20,000).

We will take the liberty of giving a brief characteristic sketch of the various groups of the Turkish working class.

The workers of Constantinople, in particular the railway workers, are the advanced section of the Turkish proletariat. This stratum of the proletariat came from the petty bourgeoisie. They are mostly children of shop assistants, petty employees, small shopkeepers and impoverished handicraftsmen. Among the railwaymen we find a large percentage of fully educated according to the Turkish standard, while some of them have even a secondary education.

The dockers, lightermen, porters and shopmen are hedged off in their medieval craft corporations. These are for the most part peasant elements among whom Kurds and Lazes predominate, who come to Constantinople for a couple of years to earn a little money and then return to their villages. The pressure of taxes pushes them out of the village into the ancient Ottoman capital where they get fixed up as boatmen, lightermen, porters, etc. Owing to their state of organisation they are enabled to establish fairly high rates of wages and all governments that have been in power, from Abdul Hamid to Kemal Pasha, have had to consider the organisation of Constantinople “Hamals” (porters) as a serious force. When the Kemalists occupied Constantinople in 1923, they tried to interfere with a view to breaking their free will. The matter ended in a formal battle between the Hamals and the police, in which a few hundred porters were injured. Here the sectionalism of the Kurds, who predominate among the Hamals, played no small role. The leaders of the organisations–the “Kekhaia”–were condemned to imprisonment. The Constantinople reactionaries carried out counter-revolutionary agitation among the discontented Kurds and they even succeeded in organising an attempt on the life of Mustapha Kemal with the aid of the Kurds, but thanks to measures being taken in time, the police succeeded in averting this attempt by means of arresting all the instigators (in October, 1923).

The Zonguldak miners are composed entirely of peasants who come to work in the coal mines for periods of three to six months. The material conditions of work in the mines are absolutely intolerable and it is physically impossible to remain in them for a more prolonged period. The peasants are generally hired not directly by the mine-owners, but by a contractor, with whom the mine-owner concludes an agreement. This contractor, or senior member of a corporation-“Tshaukh”–mercilessly exploits the members of the corporation, despairing peasants, whose needs drive them to weary toil in the mines. In 1923 a few advanced workers arriving from Germany, where they had been sent to receive a skilled training, succeeded in organising the Zonguldak miners, who organised a strike for the first time to which we will refer later.

The Committee of Union and Progress had sent during the time of the imperialist war, 1,500 young workers to Germany and Austria-Hungary to become perfected in various branches of industry. These workers lived through the November Revolution in Germany and the Hungarian Soviet Revolution, in which some of them actively participated. These skilled Turkish workers, on returning to Turkey, played an important role in the work of organising the Turkish working class. Many of them actively participated in forming the Turkish Communist Party, always acting as skirmishers for the revolutionary Labour movement.

On the whole, the Turkish working class still bears the imprint of sectionalism, craft restrictions and petty bourgeois psychology. However, the subsequent process of industrialisation of New Turkey, which is being energetically striven for by the Kemalist Government, will radicalise the Turkish proletariat and make it a class in the modern sense of the word.

The Smyrna Economic Conference.

At the commencement of 1923 the Government of Ismet Pasha summoned a special conference in Smyrna devoted to economic questions and to the tasks of raising the productivity of the country’s forces. The authorities allowed working class representation at this conference, but the delegates of the workers were appointed by the local authorities. The Constantinople workers, thanks to the initiative of the Communist group “Aidynlik” (“Enlightenment”) succeeded in organising themselves and electing three delegates, among whom was one Communist, the pioneer of the Communist movement in Turkey, general secretary and leader of the Party, Dr. Shefkit Rusin. (This comrade was recently sentenced by the Angora “Court of Independence” to 15 years penal servitude for a pamphlet on the 1st of May.)

Comrade Shefkit Rusin succeeded in rallying around him the Labour delegation at the Smyrna conference. The majority of points in the programme of the confederation on the labour question were drawn up with the participation of comrade Rusin. At the fraction meetings of the Labour delegation, the points that had been drawn up with regard to labour protection, the eight-hour working day and the right of coalition and collective treaties, were accepted. Although the Government promised to realise these demands, the entire Smyrna programme of labour legislation has remained a “scrap of paper” up to the present day. The Medjelis postponed the examination of legislation projects referring to the labour question from one session to another, never finding time to occupy itself with this matter.

The Smyrna conference gave a stimulus to the Turkish Labour movement, in which two wings made themselves apparent: the moderate “patriotic” wing and the Communists. The compositors of Constantinople, a section of the tramway workers and others were under the influence of the Communist group, “Aidynlik.” The remainder were ensnared by the swindler Shakir Rassim, to whom we referred in the first part of this article.

The 1st of May, 1923, was used by the Ismet Pasha Government to suppress the Communist movement which had begun to develop in Constantinople. The leaders of the “Aidynlik” group, with comrade Shefkit Rusin at their head, were put behind bars and a political trial was started against them, in which they were charged with treason. By these arrests, the Constantinople authorities wanted to come to the aid of their agents, Shakir Rassim and Co.

But the Constantinople workers did not allow themselves to be detracted from the path they had once chosen and the trade union movement began making still greater progress. In the middle of July, 1923, a strike movement commenced which continued sporadically for a few months. Yielding to the pressure of the working masses, who were inspired with the determination to fight for improving their economic position and for unity, the government had to close its eyes to the “unlawful” amalgamation of all “Derneks” (unions) into a general “labour union” (“Birlik”) which was a kind of Federation of Labour in Constantinople.

The Labour Union.

On November 26th, 1923, a Labour Conference took place in Constantinople at which 250 delegates were present. Both the representatives of the Zonguldak miners and of the Balia-Kara-Aidin districts participated in this Conference. The Conference was thereby given an all-Turkish nature. At this Conference it was decided to form an “All-Turkish Labour Union”–the Birlik–similar to the Confederation of Labour existing in capitalist countries. This Confederation of Labour embraced 19,000 organised workers of Constantinople (altogether 32 unions), 15,000 Zonguldak miners and 10,000 workers of Balia-Kara-Aidin.

This Shakir Rassim, of whom we have already spoken, stood at the head of this Confederation and used every effort to direct the activities of the Union along paths previously indicated by the Constantinople political police. On the insistence of the latter, the Birlik excluded all Communists from the trade unions. In an interview with the representatives of the press, the worthy secret police agent, Shakir Rassim, made the following announcement: “The Birlik pursues exclusively economic aims and is a national organisation in the full sense of the word. The Birlik has nothing in common with Socialism nor with Communism. It considers it its duty to fight against the extremists.”

In order to emphasise his devotion to the bourgeois Kemalist Government, Shakir Rassim proposed Refik Ismail Bey, secretary of the Constantinople organisation of the Kemalist People’s Party, as candidate for vice-president of the Executive Council of the Birlik. In this manner the Kemalist guardianship over the organised Turkish working class was established.

The servility of the Executive Committee of Birlik before the government of the propertied class in power, exceeded all bounds. The sending of telegrams of true allegiance to the President of the Republic, Mustapha Kemal Pasha, the bowing and scraping, the cadging for the authorities, the loud advertising of the devotion to the “national” interests, banquets in honour of various Pashas, all these means were widely applied in the practice of the police agent, Shakir Rassim. “Ghazi” Mustapha Kemal Pasha, in reply to the expression of “true allegiance” on the part of the Birlik, himself promised to support the drafting of a law on trade unions and strikes. But this law has not seen daylight as yet.

The Birlik was not able to embrace all the organised Constantinople workers. Those remaining outside the influence of the Birlik were firstly the railwaymen, secondly the printing workers who were even in opposition to the Birlik. The Communists enjoyed great influence among the Constantinople compositors. In exactly the same way, the port workers also refused to adhere to the Birlik.

The Birlik soon lost ail authority in the eyes of the workers. This can be seen, if only from the fact that by April, 1924, it had only 7,000 members whereas at the commencement it numbered 19,000 workers in Constantinople alone. The servile tactics of the Birlik, its cringing before the authorities, had the effect of turning the workers away. They had grown up sufficiently to understand that the secret police and the bourgeois Government are not hopeful defenders of the interests of the working class.

It is characteristic that the Government nourished the Birlik only with promises, whereas in reality it did not push forward the question of free coalition a single step. The Government even looks suspiciously on such a patriotic mongrel as the most loyal Birlik. The latter soon liquidated itself.1

The Strike Wave.

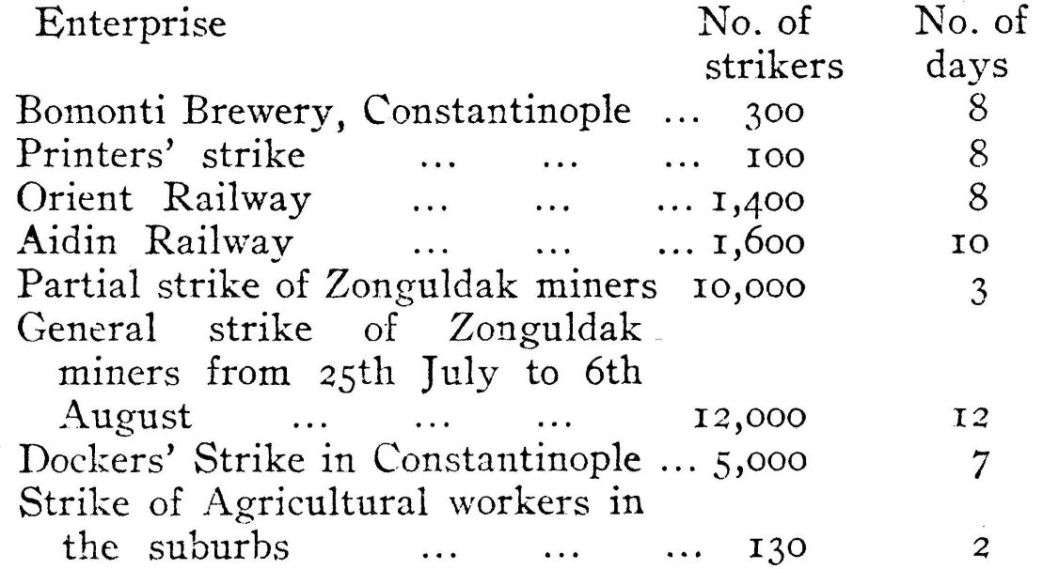

In the summer of 1923, as we have already pointed out, the working class life of Turkey was marked by serious events. In nearly all the large working class centres of the country a strike wave took place. This wave covered a tremendous area, having a number of strikers to the extent of 32,000, unprecedented for the Turkish Labour movement. On the whole, these strikes were of clearly offensive nature. Side by side with economic demands, a number of political demands were put forward such as the right of coalition, social legislation, etc. Wherever the strike was led by Communists (Constantinople printers, the Orient Railway, etc.), the demand for the closest contact with the U.S.S.R. was also put forward.

Fifty per cent. of all the strikes ended in victory for the workers. Strikes took place in the following enterprises:

These strikes marked a turning point in the history of the Turkish Labour movement. No matter how much the Government tried to put a noose around the working class, and to take the Labour movement under its guardianship, it was nevertheless powerless to stop the development of the strike movement, which at first affected several tens of thousands of workers.

In the summer of 1924 two strikes took place, one amongst the postal and telegraph employees and another among the tramway workers. The latter even had a fight with the gendarmerie, as a result of which some of the strikers were injured and 27 were arrested. This strike bore witness to the fact that the Constantinople workers had severed themselves from the “national” authorities, against whom they entered into opposition. The Constantinople workers became convinced in practice that the State “national” power is the power of the bourgeoisie, who will not stop at shooting the proletariat and acts only in the interests of the Turkish bourgeoisie and foreign· capital.

In October, 1924, a strike broke out on the Orient railway (Constantinople-Andrianople). The reason for this strike was the decision of the workers to divide up among themselves the money in the Mutual Aid funds (“Passiret”). The railway company (belonging to a French firm) intervened in this affair and discharged two of the most active workers. The workers struck, demanding that the dismissed men be taken on again. The administration of the Orient Railway, as far back as 1922, had unceremoniously disposed of the Mutual Aid funds, into which it also paid a certain share. The authorities intervened in the strike, which was liquidated by force.

During the whole of 1924 strikes frequently broke out, first in one district, then in another, and in these cases the authorities always took the side of the owners (in most cases, foreigners). For instance we all know about the strike of October, 1924, at the large mills in Constantinople and that of the textile factories (governmental), where the working women also joined in the strike. A strike that is interesting to note is the one that broke out in August, 1925, among the sailors of the society “Shirket and Hairie” (Steamship ferry service). This company is in Turkish hands and rakes in tremendous profits. But the seamen receive miserable wages.

Needless to say, the police intervened in favour of the shareholders and arrested the most active strikers. Several scores of striking seamen were sacked and replaced by strikebreakers.

In connection with this strike, which was broken up with the aid of the police, the “Djumkhuriet” (“Republic”) a Kemalist newspaper appearing in Constantinople, made the following remarks about the labour question in Turkey in its leading article of August 21:

“A section of the ‘Shirket’ workers tried to organise a strike, but this attempt failed…The Turkish worker does not command the same qualities and the same material resources as do the European workers. The working class of Turkey is still in its infancy and the labour organisations are committing an error when they urge their members to contemplate strikes…It is only malicious elements who incite the naive Turkish workers on the dangerous path of the class struggle. In Turkey big capitalists do not exist. Our economic life is still inadequately developed and, therefore, there is no room for a labour problem. With us, the owners, i.e., the people of initiative, are not to be distinguished very much from the workers in the sense of their material conditions of existence (!)…In spite of this we have to record the fact of extreme excitability and discontent among our workers, which excitement has a tendency to increase the antagonism between the workers and the owners we must not neglect this excited mood of the workers. This state may become the source of a threat to our national and economic development. It is necessary to take urgent measures to avert this threat…Organs must be formed which will lead the working class, civilise them and perfect them.”

The sense of this tirade to put it briefly means: “Let the consuls take courage!” and let those who keep in power repress the Turkish working class, holding them under their guardianship. In other words, Zubatov is alive on the shores of the Bosphorus!2

The entire Turkish press took up arms against the strikers, who had dared to tamper with the pockets of the “poor” Turkish shipping owners. The national Turkish bourgeoisie gave vent to its wrath over the working class and set going the whole machinery of the entire State apparatus.

The working class of republican Turkey is deprived of elementary political rights. The Turkish worker does not know what the eight-hour working day is. A working day of 14-15 hours is the usual thing in Turkey. The workers are forbidden to organise in modern trade unions. They are forbidden to strike, they are not allowed to form organisations which could provide for them in case of illness, old age or accident. Women’s and children’s labour is exploited in the most shameless manner. The bourgeois State, which has emerged from the national bourgeois revolution, doubly protects the interests of its own class and at the same time endeavours to squeeze the proletariat in the vice of police guardianship.

The Confederation of Labour “Teali.”

In the autumn of 1924, the Turkish Communists succeeded in cementing together a few of the Constantinople unions and forming a new Confederation of Labour, “Teali,” in place of the Birlik which had been liquidated. The Communists have a leading nucleus in the central organs of some of the unions and carry on organisational work therein, supported by their own fraction into which sympathising workers were drawn.

At the head of the Teali–Trade Union Council–there was a presidium composed almost of Communists, with the exception of the President, a Kemalist. This was the same Refik Ismail Bey who figured in the Presidium of the Birlik. This President maintained permanent relations with the Government, although he was at times compelled to carry out the instructions of the Communist fraction.

The Teali existed up to May of the present year (1925) and was closed down by the Government after the arrest of the Communist leaders, 15 in all, including both intellectuals and workers.

On May 1st, 1925, the Constantinople Communists issued a pamphlet devoted to the proletarian holiday.

The Turkish Communists developed extensive work throughout the whole of last year right up to the recent arrests. The theoretical journal “Aidynlik” began to appear more frequently, and a paper “Hammer and Sickle” (OrakTchekitch) was published to which scores of worker correspondents from Thrace and Anatolia contributed. Further about 15 various pamphlets were published on the questions of Leninism, Marxism, the Labour movement, etc.

The Government became frightened about the increasing influence of the Communists among the Turkish workers, and decided to isolate the Communists from the workers. It arrested several responsible Party workers who were sent to Angora and handed over to the “Court of Independence.” The court sentenced them to a total of 159 years penal servitude. Only four comrades succeeded in slipping out of the hands of bourgeois justice. Thirteen comrades remained in the clutches of the Angora jailers. The Government dosed down “Aidynlik,” “Orak-Tchekitch” and “Yoldash” (“Comrade”), which appeared in Broussa; the Executive Committee of the Teali was dissolved and a reign of violence and arbitrariness was established in the country.

During the recent times the Government, owing to the strike movement of the last few months–in particular the strike which broke out in the shipping company “Shirket and Hairie”–decided to take the Labour movement completely into its own hands. It is understood that if the workers were to be left in a scattered and isolated state, the movement might acquire very dangerous forms.

The Government of Ismet Pasha deemed it necessary to give the workers some appearance of an organisation “pursuing exclusively economic aims, having nothing in common with politics” as the Constantinople paper “Djumkhuriet” put it. The Government thereby hoped to avert the discontent of the workers and to divert their attention from political questions.

On August of the present year, with the permission of the police, a meeting was held in Constantinople of the “Union of Workers’ Mutual Aid of Stamboul.” In place of the old Executive Committee of the “Teali” a new Executive Committee was elected, in which the well-known secretary of the Kemalist organisation in Constantinople, Dr. Refik Ismail Bey was “unanimously” appointed president. At this meeting it was decided to issue a statement in which it would be declared that: “The workers are by no means interested in political questions.” “This was not their affair.” said the statement.

This is not the first time the Kemalist Government has tried its hand at suppressing the Labour movement. It has driven the Communists underground, deprived the Labour movement of its leaders, shut down its newspapers and once more tried to throw dust in the eyes of the workers.

Vain endeavours! The progress of capitalism, which has been so energetically promoted by the Kemalist Government, will mercilessly destroy all the barbed wire fences separating the workers from “politics,” will knock down all the houses of cards, set up by the official guardians of the secret police. The workers will all the same become mixed up in “politics”; for if you push nature out by the door it will come in through the window! The Labour movement of Turkey will wrench itself out of the clutches of the Kemalist Zuhatovs and will enter the path of class development. The Kemalists will not be able to hold back the wheel of history, will not be able to avert the inevitable.

The process of industrialisation of Turkey formed an adequately extensive task for developing a mass Labour movement which will be all the more revolutionary, the tighter the Kemalist guardians try to press the class Labour movement within their vice.

NOTES

1. One may also recall the revolutionary trade union organisation “The International Union of Toilers of Turkey,” which even had its own newspaper. But this organisation embraced only the working class elements of non-Turkish origin and could not enjoy any influence among the Turkish workers. This organisation existed three years.

2. Zubatov was a Tsarist agent provocateur who organised “loyal” trade unions.

P. KITAIGORODSKY.

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/new_series/v02-n17-1925-new-series-CI-grn-riaz.pdf