Compared to renting in the United States today, Vienna’s Social-Democratic housing of the 1920s seems like a Communist utopia.

‘Vienna Today: How the Socialist-Labor Government Houses the People’ by Ernst Toller from Labor Age. Vol. 16 No. 4. April, 1927.

We have thought that it would interest our readers to run an occasional account of what the workers of other lands are doing. The first of these intimate sketches is by the noted German poet, Toller. In Austria the Socialist and Labor Movements are closely allied, and we have here a pen picture of their joint work for the Viennese working population.

“REPUBLIC SQUARE!” cried the conductor of a motor bus in Berlin. People standing on the foot-board laugh. “Wotcher want me to say?” said the conductor indignantly. “Duty is duty.”

This little episode, observed recently by a friend of mine, is symptomatic and instructive. For years there was a Socialist majority in Berlin. Of its labors only the name “Republic Square” remains—and that is merely an official designation.

My companion in the Vienna-Berlin train tells me that he is an Austrian manufacturer. We discuss Viennese local government policy. The subject puts him in a red rage.

“You in Germany have reasonable Socialists. But ours—worse than the Bolsheviks. The middle classes can no longer exist in Vienna. They are slowly strangling the capitalists. Without a great outcry. Gradual bloodletting. Not long ago I went to look at one of the great workers’ palaces; I thought I should burst with rage. And people like us must limit our expenditure more and more. What can one do? I have dismissed our fourth maid-servant and the chauffeur. Just think, I pay a tax of 50 schillings for the first maid-servant, for the second a further 150, for the third 600 more, and for the fourth another 1200. Nobody can afford that. Vienna is going to the dogs. The owners of the night clubs have said that they will close if Breitner does not come to his senses. One of my friends, who owns a night club, told me that a bottle of French sack costs eight schillings, besides 16 schillings tax; and of the 24 schillings Breitner gets 60 per cent in communal taxes in the night clubs.”

I too have recently seen what the Vienna Town Council is doing; it has a strong Socialist majority, and I saw Socialism in practice to an extent which struck me powerfully and destroyed the feeling of depression which is becoming the settled mood of German Left wing Socialists. In Austria the Left wing remains within the Socialist Party.

The Town Council has secured immense revenues by means of the tax on houses. The leader in financial policy is Breitner, best loved of the people, best hated by the capitalist classes.

Houses and flats are taxed according to their amenities and the number of rooms. On small dwellings the tenant pays a merely nominal sum in rent and tax (for rents are determined by legal enactment), but for an eight-roomed house the tenant pays 300 schillings a month in communal tax. The rate per head for house tax in Vienna is 172 schillings, whilst in America, for example,. the rate is only 56 schillings, although wages and salaries: are for the most part higher. From the yield of the house tax workers’ dwellings, children’s playgrounds, maternity homes, temporary homes for orphans and deserted children, workers’ colleges, public baths, and so on, are erected. The best architects are engaged to plan the houses.

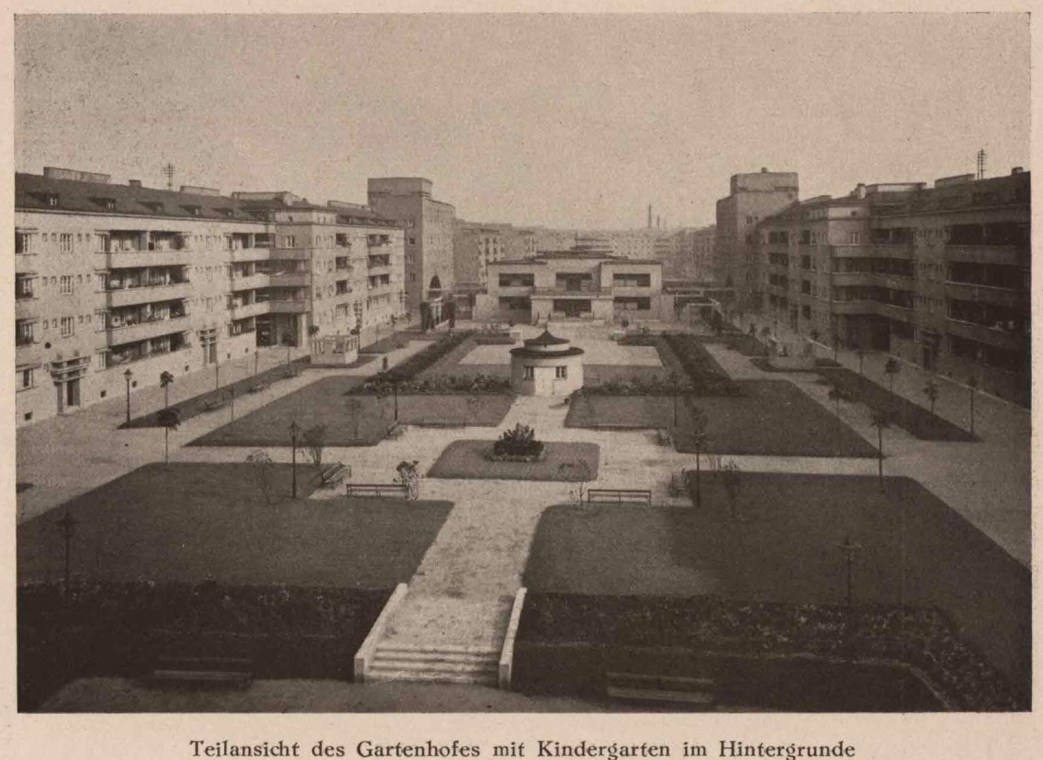

Winarsky-Hof

The Winarsky-Hof, named after a Socialist worker now dead, is one of these vast buildings, consisting of a number of houses with airy courts between then, planted with trees. This building contains eight hundred families, and three thousand four hundred souls. Of these, twelve hundred are members of the Socialist Party. (There are three hundred thousand organized Socialists in Vienna.) The smallest flat includes a bedroom, kitchen-livingroom, and entrance; most have two rooms and a kitchen. Every room has a parquette floor, every house a central washing and drying room, a common kindergarten, library, hall for meetings, cinema, and committee room. Just think what it means for working women, to be able to leave their children at home when they go to work, to pop their washing into an electric boiler in the great wash-house, and to finish with a turn of the hand what used to take them one day, or even two; besides which, the clothes no longer fill the home with steam while they are being washed and dried.

I look at the library, with its tables and chairs designed by Peter Behrens. I open the catalogue of belles-lettres at random and read under the letter F: Flake, Flaubert, Fontane, France, Frank. I go to the cinema, a great hall which can be converted into three smaller ones by a mechanical device which lets down walls. From the school near-by the children are watching a natural history film, which teaches them geology in a really vivid way. The programme for the evening announces the Russian film, “The Bay of Death”, and “Man Amongst Men”. From time to time good concerts, lectures, and dramatic entertainments are held in the cinema.

No one who has seen the former slums of Vienna can realize what the town has accomplished.

On every house, clear to be seen, the legend is written up on a tablet: “Built from the yield of the house tax”,—a joy to the rich.

The architectural appearance of the buildings is various. Those erected a few years ago (for example, the Fuchsenfeldhof) are decorative, like palaces; those put up recently are plain and sober, designed for use Decorative Gaiety

It seemed to me significant that as a general rule the workman likes decorative gaiety, and lacks appreciation of modern simplicity in architecture. Why? Modern architecture has turned from gay luxury and excess to simplicity. It has passed beyond luxury, and has taken over from it only so much as serves its new purpose. The worker has grown up in want. Everything in his former dwelling was grey and uniform. Luxury for him was a dream of desire. Think of his love for films where the action takes place in magnificent houses. He longs for a little decoration, which he may be able to recognize only in the form of frivolous ornament, and here once more is sober simplicity. The difference in quality between this kind of simplicity and the simplicity which he knew in the past is not felt by him, and so his dissatisfaction is easy to understand. It seems that the present generation of workers must follow the errors of the capitalist classes for a time, in order that they may win the power of combatting them with the innermost conviction.

It is true that in such large buildings there are small squabbles. For the people who enter their doors are animated but little by cooperative consciousness. One woman is annoyed because another in the central washhouse peers at her washing; another woman declares that her neighbor is ordering her about. But it may be observed that these quarrels, which are settled by a specially constituted House Committee, are growing fewer and fewer, and that cooperative consciousness is on the increase. In cases where one tenant loses his work, his neighbors club together and help in a fine spirit of solidarity.

The Old Adam

It is another question whether these agglomeration of flats—palaces or barracks—are the ideal solution of the housing problem in large towns. I will confess honestly that, much as I admire what has been accomplished, settlements or colonies seem to me wiser. There are a number of well arranged settlements in Vienna also. But a ring of settlements round a large town is only possible if good and rapid transport exists; otherwise the worker wastes two or three hours in travelling to and from the factory. Nor am I blind to the fact that there is a danger, for those who are the product of our modern school and education, that in a settlement they may become quarrelsome and narrow—cultivating their cabbages, squabbling with their neighbors, wanting to be left in peace, and troubling about their brother workers not at all.

Always the same problem confronts us: we must create new forms of organization, but we must realize that the old Adam will enter into them, and that only kindly compulsion will restore in his soul the starved instincts of cooperation.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v16n04-apr-1927-LA.pdf