Foster knew the French workers’ movement well, spending much time there reporting on it for decades. A visit in 1924 saw this analysis of the debates and divisions in the unions and the role of the Communist Party.

‘Aspects of the French Labor Movement’ by William Z. Foster from Labor Herlad. Vol. 3 No. 4. June, 1924.

SINCE the formation of the Communist International five years ago many new developments have taken place in revolutionary organization. Various forms, previously unknown in most countries, have been developed and popularized. Among these are shop councils, shop nuclei, and trade union committees. In Russia, the vanguard of the revolution, these vital proletarian institutions are highly developed. In all the other countries of an industrial character they are on the order of business and are coming into existence with greater or lesser speed. At the present time the French labor movement, industrial and political, is re-aligning itself according to these new needs. What progress is being made and how it is taking place should be of interest to American militants.

Shop Councils

Shop councils are organizations of the workers directly on the job. They are delegate bodies of all the workers employed in given enterprises. Being right in the shops, they are much closer to the masses and their problems than local trade unions can ever be. They are the basic mass industrial revolutionary organizations. When militant and well organized under capitalism they exert a strong control over the “hiring and firing” of workers; they see to it that all union regulations are scrupulously respected by the employers; they closely follow the course of their industry and undertake to learn the intimate details of how the business is conducted.

In case of strikes the shop councils, as they represent all the workers, unorganized as well as organized, bring much larger masses into the struggle than the trade unions can bring. Eventually the shop councils are destined to become the real local units of the trade unions. They are always industrial in form. But it is during the revolutionary crisis that they play their supreme role. It is by means of them, as in Russia, that the revolutionary workers actually take charge of the industries and make the first efforts at operating them under the new social order. In the reconstruction period they are the means to put into effect the industrial policies of the workers’ government.

From its inception the Communist International has realized the great importance of the shop councils and it has ceaselessly stimulated the labor movements in the various countries to build up shop councils. Great progress has been made in Germany, but it is with the French movement that we are dealing here.

The shop councils movement in France is about two years old. It has taken on importance only since the formation of the C.G.T.U. (Unity General Confederation of Labor.) This revolutionary organization is giving them whole-hearted support. It is interesting that the reformist C.G.T. (General Confederation of Labor) is opposed to the shop councils on principle, claiming that they are by nature rivals of the trade unions. In Germany the reformist leaders have about the same attitude, although they dare not express it so frankly. They content themselves with quietly cutting the heart out of the shop council movement–one of the few conquests of the 1918 revolution—while at the same time pretending to be friendly to them.

The shop councils movement in France, although intended for all industries, is at present making greatest headway among the miners, textile workers, furniture workers and metal workers. In each case it is the unions that are taking the lead. But as they are very weak they are unable to set the movement up properly from the start. They do not as yet actually found the shop councils, except in a few instances. The stage the movement is in a present is the calling of meetings of delegates from the various shops, factories or mines in a given industry and district. These delegates are elected by the workers, organized and unorganized, at such mass meetings of them as may be called in connection with the various plants. Later, the actual shop councils are formed.

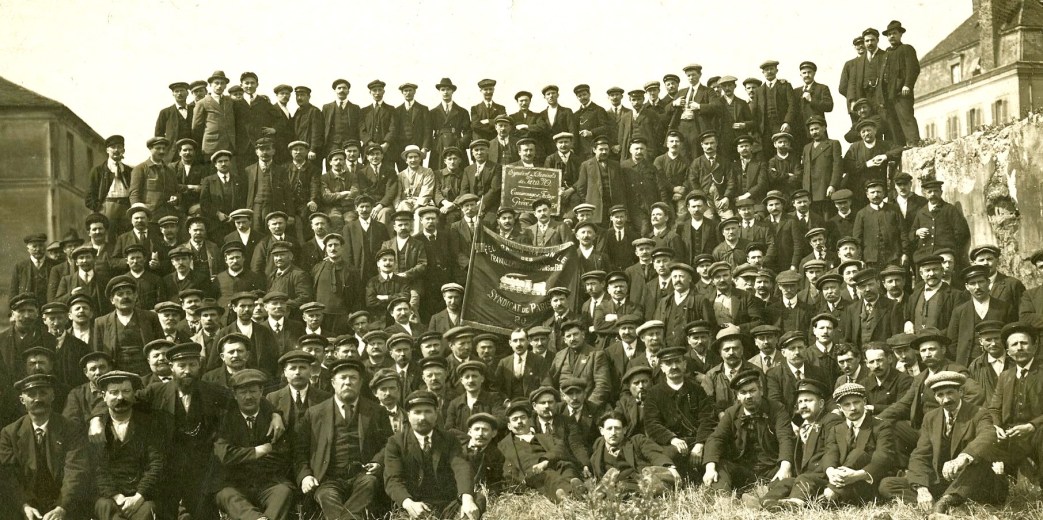

Many meetings of delegates so elected have taken place recently in France. These meetings take on the aspect of conventions. On March 9th, 600 delegates, metal workers, representing 250 plants, principally in the Seine district, met at Paris. On the same day 195 miners’ delegates held a similar convention in Denain. They represented nearly all the mines in the district. Some were affiliated to the C.G.T.U., some to the C.G.T., and many were unorganized. Conferences of a like character are being called in various other industries and districts. The whole C.G.T.U. is stirred by the shop councils movement.

Briefly, the immediate aims of the movement are as follows: 1) To build up the shop councils in all industries. 2) To build up the trade unions. 3) To develop the demands of the masses and to secure the support of these masses in the struggle against the employers. The movement takes on greater volume with the passing months, particularly in view of the pressure now being put upon the French working class by the rapacious employers. This movement is doing much to enhance the already great prestige of the C.G.T.U.

Shop Nuclei

Shop nuclei are political organizations based upon industry. They serve eventually as the bases of the Communist Party, even as the shop councils must be the foundation of the trade unions. The shop nuclei consist of organizations of all the Communists within a given enterprise or industry. They bring the political struggle of the Party right into the shops. They are a revolutionary departure from the old territorial form of organization developed by the socialist parties everywhere. They root the Party right in the heart of the industries where the class struggle rages ceaselessly. Thus they enable the Party to really function as the vanguard of the proletariat, by so situating it that it can dominate the shop councils and lead the workers in their daily struggles.

The shop nuclei lock the political and industrial movements together and make of them one rounded organization. Just as the trade union movement needs the shop councils to actually put it into contact with the great laboring masses and their problems, so the Communist Party needs the shop nuclei for the same purpose. Without shop councils and shop nuclei both the industrial and political movements of the workers must remain disjointed and largely isolated from effective contact with the masses.

Even as in the case of the shop councils, the Communist International, from its inception, has recognized the supreme need of shop nuclei. At its First Congress Zinoviev stressed this point heavily. Nor has the C.I. ceased pounding upon the matter since. It has now come to be generally understood that a party cannot really be a Communist Party unless it is actually based upon organized nuclei in the shops, mines and factories. Consequently, throughout the International, the shop nuclei movement gathers headway. More and more the revolutionists are breaking with the old social-democratic idea of organization simply by industry or geographical division and are taking on the shop nuclei form, which has proved the backbone of the Russian revolution and which is so strongly insisted upon by the Communist International.

But the reorganization of the Party from a purely territorial to a shop nuclei basis, despite its advantages, is not being accomplished in the various countries except slowly and with much difficulty. This is the case in France, as well as elsewhere. Only in April, 1923, did the French Party seriously take the matter in hand and launch the shop nuclei movement definitely.

This has now taken on considerable volume, especially in the larger centers. At present the Party is organized territorially. In the future it will have two bases: where the workers work and where they live. In Paris and other big industrial centers nuclei are now being organized in all the principal industries. For the time being the dues collecting function is being left to the local branches, as before, but eventually the shop nuclei will take this over. As the movement requires substantial volume in the big cities, it will be gradually spread to the smaller places, until eventually the whole Party, or as much of it as can be so adapted, will be reorganized on the shop nuclei basis. Whatever the difficulties confronting it, and however slow its progress, the French shop nuclei movement, even as that of the shop councils, is definitely under way and is being taken seriously by the militants.

Trade Union Committees

One of the big issues in the French trade union movement (the C.G.T.U.) for the past two years, was the question of the organization of trade union committees by the Communist Party.

In 1921, at its Marseilles Congress, the Party decided to form such committees, or nuclei. But nothing definite was done about it. Frossard was secretary and, having the Jauresist conception that the Party should stand aside, attend to its own political work and leave the trade unions alone to perform their industrial functions, he sabotaged the whole project so long as he was in office. The Party committee that had been appointed accomplished practically nothing. In 1922, at its Paris Congress, the Party took the matter up again and laid more elaborate plans for a national trade union committee, together with corresponding committees in all the national and local unions. Their function was to organize and propagate communism in the unions.

This action at once made the matter a burning issue in the C.G.T.U. The opposition, consisting of “pure” syndicalists, anarchists and Frossardists, made a wild protest. They declared that if the Communist Party were allowed to have such committees it would be the end of the trade union movement as such, for it would lose its independence and degenerate into merely an appendage of the hated Communist Party. They emphasized this issue as an argument against affiliating to the Red International of Labor Unions.

The matter came to a head in the Bourges, 1923, Congress of the C.G.T.U. By a strong majority, the Congress decided not only in favor of the R.I.L.U., but also to permit organized revolutionary propaganda within its ranks provided that the members of these nuclei would submit unquestionably to the decisions and discipline of the unions. The whole issue threatened to split the C.G.T.U.

But, after creating all this commotion, the trade union committees have not amounted to much. There is a national committee of 13 members (appointed by the Party) but they are not very active. There are also a few committees in the larger centers but they are not very active or well organized. Pierre Monatte, a veteran militant in the French labor movement, was one of the three national secretaries of the trade union committee. He recently resigned and levelled a strong criticism at the whole system. In the pioneer land of organized trade union nuclei, the trade union committees are not making much headway.

The Triple Movement

All three of these movements—shop councils, shop nuclei, and trade union committees are necessary to the labor movement. The shop councils are the basic organization industrially of the masses; the shop nuclei are the organized revolutionists within the shops and the shop councils, and the trade union committees are the organized revolutionary nuclei within the trade unions. They do not conflict with each other, but complement and complete the general revolutionary structure.

But France, like other countries, is finding out that it is a real task to learn the functions of these new forms and to adopt a balanced program with regard to them. At present there is a tendency towards a sort of faddism in the matter. Instead of following a broad policy which includes all three of the movements, each in its proper place, there is a tendency to favor one or another of the movements at the expense of the rest. In such a competition the trade union committees are not faring very well. They represent an old, tried, and homely movement and do not attract as much attention and service as the newer and more glittering shop councils and shop nuclei movements.

The working out of a real balanced program, with all three movements given their proper function and place, is, therefore, one of the most urgent needs now confronting the French labor movement. What is wanted is a comprehensive plan embracing at once the shop councils, shop nuclei, and trade union committees.

The Labor Herald was the monthly publication of the Trade Union Educational League (TUEL), in immensely important link between the IWW of the 1910s and the CIO of the 1930s. It was begun by veteran labor organizer and Communist leader William Z. Foster in 1920 as an attempt to unite militants within various unions while continuing the industrial unionism tradition of the IWW, though it was opposed to “dual unionism” and favored the formation of a Labor Party. Although it would become financially supported by the Communist International and Communist Party of America, it remained autonomous, was a network and not a membership organization, and included many radicals outside the Communist Party. In 1924 Labor Herald was folded into Workers Monthly, an explicitly Party organ and in 1927 ‘Labor Unity’ became the organ of a now CP dominated TUEL. In 1929 and the turn towards Red Unions in the Third Period, TUEL was wound up and replaced by the Trade Union Unity League, a section of the Red International of Labor Unions (Profitern) and continued to publish Labor Unity until 1935. Labor Herald remains an important labor-orientated journal by revolutionaries in US left history and would be referenced by activists, along with TUEL, along after it’s heyday.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborherald/v3n04-jun-1924.pdf