In the 1910s, the U.S. became a majority urban-living country as millions left farms for factories. One of the country’s great social shifts. A close look at the numbers in the push and pull of urbanization.

‘The Mass Migration of American Farmers’ by A.G. Richman from The Communist. Vol. 8 No. 5. May, 1929.

THE movement of over ten million persons from American farms during the last five years makes up one of the greatest migrations of recent history. Rationalization and the agricultural crisis (the scissors, etc.) which began in 1920 and still continue, are resulting in the evolution of the American farmer among those who remain on the farms, at the same time that they are driving millions away.

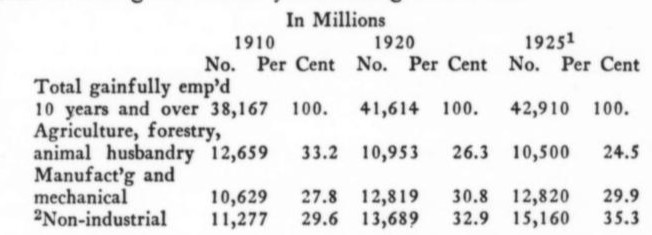

The relative distribution of the agricultural working population as compared with the gainfully employed population (workers, employees, employers, etc.) in the various industries has been as follows during the fifteen years ending with 1925:1

This data shows that between 1910 and 1925 the agricultural population has not only declined absolutely but relatively as well, whereas the proportion of industrial workers has declined only slightly, and that of non-industrial workers has increased greatly both numerically and proportionately. This is but one of the results of the U.S. becoming to an ever-increasing extent a rentier and commercial nation, at the same time that it remains the greatest industrial nation in the world.

Of the farm population, about one-third are gainfully employed on the farms, the rest being small children and women. Of those gainfully employed, about 40 per cent are farm laborers (4,200,000), of whom over one-half are hired laborers and the rest family labor; 30 per cent are tenant farmers; 20 per cent mortgaged owners, and only about 10 per cent owners free of mortgage.

The bulk of child labor is in farming. In 1920, 61 per cent (650,000) of all children gainfully employed between the ages of 10 and 15 worked on farms, and 81 per cent (330,000) of all children between 10 and 13 worked on farms. One-tenth (,040,000) of all persons gainfully employed in agriculture were women.

During the past five years (1924-1928), 10,203,000 persons have left the farms: 1928—1,960,000; 1927—1,978,000; 1926—2,155,000; 1925—2,035,000; 1924—2,075,000. On January 1, 1929, the farm population of the country was 27,511,000, a net loss of 4,103,000 as compared with 1920, and the poorest point in 20 years. (1909 was the peak year, with a farm population of 32,000,000).2

The former head of the U.S. Bureau of Agricultural Economics, Tenney, has characterized this migration as follows.

“It is a tragic readjustment, and no one will ever fathom the human misery it means. Long continued, it might result in a deplorable degradation of the rural population as well as its numerical reduction.” (Magazine of Wall Street, April 21, 1927, p. III.)

This was a remarkable admission from a government official, whose task seemed to be to hide or explain away the social significance of the statistics gathered.

Lenin summed this up well, when he said about migration from American farms:

“The investigators do not even seem to suspect what amount of need, oppression and desolation is hidden behind these routine figures.” (“New Data on the Laws of Capitalist Development in Agriculture.)

A typical example of this we shall refer to shortly. The decrease, small though it is, in the number leaving the farms in 1928 and 1927, as compared with 1926, was due, according to the Department of Agriculture, to the decrease in industrial employment in the cities. But such questions are not asked. Beyond the official routine conclusion: the agricultural population declined during 19001910 from 59.5 per cent to 58.7 per cent, investigation does not venture…The bourgeois and petty-bourgeois economists refuse to take note of the obvious connection between the desertion of the farm and the bankruptcy of the small producers.

Taking the various geographical divisions of the country, we find that migration from the farms was general throughout the country in 1928:

The above table shows that every geographic division in the country showed a net loss in farm population during the past calendar year, except the south Atlantic and the east south central states (the “Old South”). As stated before, however, net movement to or from farms is far more significant than net loss, which includes births and deaths and complicates economic with natural causes. Every division in the country shows a movement away from greater than the movement to farms.

In the western states the movement from the farms was very large, nearly 15 per cent leaving from the mountain states, and nearly 13 per cent from the Pacific states. In New England, which is a decaying economic section of the country, 10.2 per cent left. Even in the sections which show net increases, 4.9 per cent (south Atlantic) and 5.6 per cent (east south central) left. For the whole country, 7.1 per cent of the agricultural population left the farms last year.

The most recent data the Department of Agriculture has on the causes and character of this migration from and to farms, is a mimeographed analysis dated October, 1927, which is a study of 2,745 farmers who left the farms between 1920 and the summer of 1927, and of 1,167 who came to farms from towns and cities. While the number is small, it seems to represent a cross section. At any rate it represents beautifully the methods of the government statisticians referred to by Lenin.

The table in the study which gives the ages at which farmers left the farms shows that owner farmers of various ages left in about the same proportion, and not more of the older ones. This indicates that those leaving did not retire, and other information available on taxes, mortgages, tenancy, etc. shows that they are being forced off. This is further reinforced by data on tenants leaving, who do so mainly in the younger age groups.

The table of present occupations of former farmers is interpreted in a deliberately misleading way. Of the 1,326 answering the question on their present occupations, 25.6 per cent are grouped indiscriminately under the heading “all other occupations,” so that we cannot tell what their present class status is. Another 23.3 per cent are grouped as “no occupation,” with the note “retired.” We would assume rather that a goodly number of these are unemployed, or in a transition stage, not yet having found work in the cities. Fifty per cent of the rest are laborers, workers in industry, etc.; 32 per cent are government and city employees, teachers, salesmen, real estate agents, etc.—mainly “white collar slaves,” as they are popularly called, or the salariat; 13 per cent are merchants, grocers, dealers in coal, feed, etc., and 5 per cent are listed as “garage, service station,” though whether they are workers or owners, there is no way of telling.

These figures do not check with the conclusion reached by the author of the study (C.J. Galpin, economist in charge of the Division of Farm Population and Rural Life):

“Not being able to make ends meet, while on the farm, was the chief reason that a full third of these migrants gave for leaving. Financial ability to live in the city counted with one farmer out of every forty.”

We have a gross underestimation of the number forced to leave the farms through poverty and bankruptcy, together with the admission that only 2% per cent who leave are able to retire.

Ex-Secretary of Agriculture, Jardine, corroborates this in his comment on this study: only 2% per cent “left after having gained a competence.” (U.S. Daily, Mar. 2, 1918.) His predecessor, H.P. Wallace, stated in his 1923 report that 91 per cent of those leaving the farms did so to better their financial status, 6 per cent because of old age, and 3 per cent for other reasons (the two latter groups delightfully vague as to economic causes).

In the table in this study on the part of present income received from farms by these ex-farmers, we read that 22.2 per cent receive 70 per cent or more of their income from the farms, which they still own, that 9.3 per cent get 50-60 per cent of their income, etc. But if we look further, we find that of the 1,635 answering this question, 450 or 27.4 per cent did not specify what percentage they now received, and 258 more, or 15.8 per cent said they got none of their income so. If we remember that, as bourgeois economists admit, only 2% per cent of those leaving the farms can retire, we see the contradiction.

A study by Prof. Zimmerman, of the University of Minnesota in 1925 and 1926, involving 500 farm families, showed that children of more successful farmers (those with greater incomes) stayed on farms to a far greater extent than those of less successful ones, who migrated to cities to become workers. Of the latter, he found that 38 per cent became unskilled laborers, 23 per cent semiskilled or skilled workers, 17 per cent clerks or employees, 17 per cent professionals (many of them nurses), and 4 per cent owners of businesses. (Amer. Journal of Sociology, July, 1927, p. 241 ff.)

The great employment of child labor on farms, even of children of owners, is another “drawback” with a distinctly economic basis. A conscientious parent who cannot give his children the semblance of an education is likely to want to move. Only one-ninth of 6,440 children of the ex-farmers mentioned in the Department of Agriculture study (by Galpin) had finished more than the first 12 years of school (elementary and secondary schools). More than half (54 per cent) went no further than the first 8 school years, and 13 per cent went no further than the first 4 years. For tenants’ children alone, the figures were far worse than those for both owners and tenants. Only one-sixteenth finishing more than the first 12 years, 65 per cent going no further than 8 school years, and over 26 per cent going no more than 4 years.

The causes of the migration described above are, of course, the poverty and bankruptcy brought about by the farm crisis. Rationalization and greatly increased productivity (despite the decrease in the number of farms and farmers, the ravages of disease and pests, the decrease in the acreage of crop lands, and the continuing decline in the number of horses and mules and therefore in the amount of fodder grown) have been contributory factors. Mechanization and other forms of rationalization have made tremendous strides recently, and have forced out many a poor farmer already on the verge of bankruptcy.

One must distinguish between the condition of agriculture as an industry, and the condition of the farmer, for the one is flourishing and continually increasing its productivity, whereas the latter is in extremely bad and ever-worsening straits. A Department of Agriculture economist, A.P. Chew, in an article entitled “Drop in Farm Population Due to Rising Efficiency,” (N.Y. Times Analyst, Oct. 7, 1927), argues that despite the depression of the last seven or eight years,

“Increased production with less labor and less land is evidence, not that agriculture is failing, but that it is dealing with its problems efficiently. There is no need to worry about the future food supplies.”

Here is a deliberate attempt to confuse increased production and capacity to produce, due to greater use of new machinery and other forms of rationalization, with the condition of the farmers themselves. This can be shown by another statement he makes to the effect that the decrease in the agricultural population

“is by no means wholly due to the agricultural depression. While it is part a reaction from the over-expansion of agriculture during the war period, it is to a much greater extent the result of technical progress in farming, which has greatly reduced the number of men necessary to produce a given amount of food for fibres.”

The decrease in population, he continues, is due much more to the use of labor-saving machinery “than to the forced abandonment of agriculture by farm operators.” The contradiction, if not confusion, is obvious. The depression in itself caused a great drop in farm population through the mass abandonment of the farms. But the introduction of labor-saving machinery at this time has been a contributory factor in continuing and deepening the depression, by increasing the productive capacity of the richer and well-to-do farmers and thus crowding out hundreds of thousands of poorer ones who were already at the margin of bankruptcy and unable to afford the cheaper productive methods of the new machinery.

The basic cause for the great migration from the farms has been the economic crisis—the “scissors,” the great and increasing burden of interest and taxation, and the tolls taken by the railroads, grain elevators, banks and trusts generally. With expenses increasing continually, and profits almost at a vanishing point, with the intensely keen competition caused by greater and greater mechanization on the part of the richer farmers and farm corporations, the astonishing thing is that the migration from the farms has not been even greater.

Practically half of all farmers in the U.S. no longer own their farms (they are tenants, managers or part owners) and nearly half of the value of farms belonging to full owners already belongs to bankers, mortgage brokers, local merchants, etc. With farmer’s debts amounting to over fifteen billion dollars, and the value of all farm property not much more than two or two and a half times as great, with taxation increasing steadily and bankruptcy of farmers growing very rapidly—we can realize what forces are operating to drive the farmers off the land.

There are two or three times as many farmers in the country as could produce the present quantity of agricultural products by using machinery already invented and proven practicable. The factory farm already exists in the U.S., working acreages of from 40,000 to 100,000 acres successfully. With the new machinery available, the doom of the small family farm seems likely. When one considers these basic factors one realizes why the present migration has taken place, and why it must continue.

The demand for the great agricultural staples has probably reached the limit of consumption in the U.S., except as population grows. During the present century industry has become less dependent on farm and forest products and more so on mineral, metal and chemical products. The food, textile, and leather industries have not grown as fast as the metal and chemical group. As a result of this relatively static demand for such agricultural products, together with the enormous increase in productive capacity and the growing competition of other countries, one need not look very far for one important cause for agricultural depopulation. The basic cause, however, is the deliberate scissors policy of the Wall Street government. The tariff policy, taxation, and mortgage banking laws, the refusal to permit the formation of real agricultural cooperatives and pools, the monopolistic prices of the farmers’ consumption goods, high freight and elevator rates, and the absolute denial of any relief legislation (despite the calling of a special session of Congress for that ostensible purpose )—these are some of the reasons for the chronic, one could even say acute, agricultural crisis of the past decade, and for the endless circle of migration from and back to the farms.

Hoover’s proposals to the special session of Congress are the creation of a Federal Farm Board, undoubtedly, as is usual, with banker members, and finance-capital in complete control of policies. This Board will “relieve” the farmers as the present Federal Farm Loan Board did in the cotton crisis of 1926, when Wall Street and local bankers got most of the money made available by the government, and the farmers got prices far below the cost of producing their crop.

1. Estimate of National Industrial Conference Board. Non-industrial includes trade, clerical, public service, professional, domestic and personal service.

2. From mimeographed release of Dept. of Agric., Mar. 14, 1929.

There are a number of journals with this name in the history of the movement. This ‘Communist’ was the main theoretical journal of the Communist Party from 1927 until 1944. Its origins lie with the folding of The Liberator, Soviet Russia Pictorial, and Labor Herald together into Workers Monthly as the new unified Communist Party’s official cultural and discussion magazine in November, 1924. Workers Monthly became The Communist in March, 1927 and was also published monthly. The Communist contains the most thorough archive of the Communist Party’s positions and thinking during its run. The New Masses became the main cultural vehicle for the CP and the Communist, though it began with with more vibrancy and discussion, became increasingly an organ of Comintern and CP program. Over its run the tagline went from “A Theoretical Magazine for the Discussion of Revolutionary Problems” to “A Magazine of the Theory and Practice of Marxism-Leninism” to “A Marxist Magazine Devoted to Advancement of Democratic Thought and Action.” The aesthetic of the journal also changed dramatically over its years. Editors included Earl Browder, Alex Bittelman, Max Bedacht, and Bertram D. Wolfe.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/communist/v08n05-may-1929-communist.pdf