1910 was a year of strikes in New York City. Here Elizabeth Gurley Flynn details the scene as thousands of delivery drivers struck multiple express companies in the fall of that year.

‘The Expressmen’s Strike in New York’ by Elisabeth Gurley Flynn from the International Socialist Review. Vol. 11 No. 6. December, 1910.

SENSATION loving New York was startled two weeks ago by an armed battle among desperate men in the streets adjacent to the Grand Central depot and by riots around the ferry houses and on the ferry boats in mid-river, in which policemen were assaulted by “the mob.” Then only did the modest demand of 10,000 men for an eleven-hour workday and a wage of from $50 to $80 per month, obscure temporarily the blatant Roosevelt and vituperative Hearst of the all-absorbing political campaign.

The strike commenced among the drivers and drivers’ helpers of the United States Express Company, a corporation: whose profits are so enormous that they pay 3 per cent dividends semi-annually on $10,000,000—over seven million of which is computed to be watered stock by the Merchants’ and Manufacturers’ Association of Milwaukee. This means 10 per cent “earnings” semi-annually on $3,000,000 actual capital. A splendid outpouring of rebellious workers from all the other express companies, and many department stores, followed, which included the employes of the Wells Fargo, Adams and American companies.

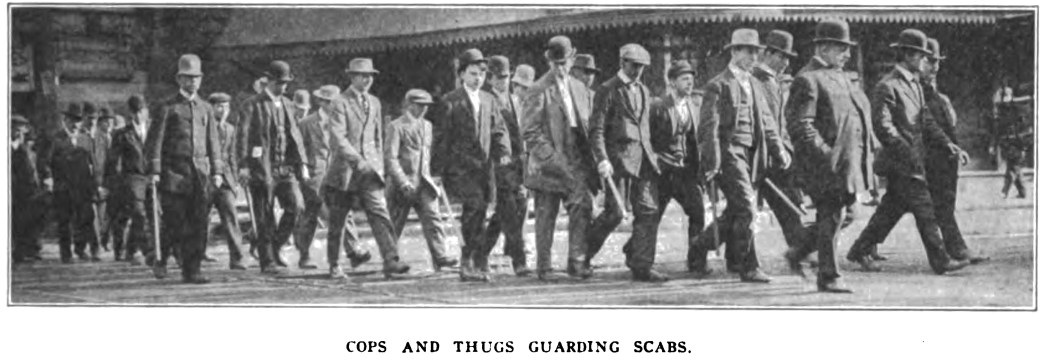

Fake employment agencies had opened up for business throughout the city a few weeks previous, and they at once proceeded to furnish strikebreakers. The kind of “men” they furnished, callow country youths or thugs, either could not or would not do the work and expressage was rapidly at a standstill. Within three days the companies claimed a loss of $100,000 per day and 500,000 packages were tied up in the Grand Central station, also cars stalled along the railroads west to Chicago. This in spite of the fact that the strikebreakers are receiving $4 per day and meals and are under police protection.

Attempts were made to deliver bundles by messenger service, whereupon eleven boys of the W.U.T. Company walked out; also by the taxicabs of the Westcott Company, which brought out 200 chauffeurs.

Consternation reigned among the politicians of the Democratic party. A labor dispute just before election would materially endanger their chances for victory. But when the conflicts occurred in the streets of New York and Jersey City, Mayor Gaynor allowed policemen to mount the express wagons and with drawn clubs they protected the strikebreakers. Up and down Broadway was seen the shameful spectacle of blue-coated officers diverted from their supposed task of keeping traffic orderly and protecting pedestrians, to their real mission of protecting private property for the class in whose services government is operating today. (A rather pointed lesson to “Home Rule” advocates and Irish Nationalists were these Irish police “scabbing’” on Irish strikers.)

Lawyer Platt, son of the notorious late U.S. Senator, emboldened by Mayor Gaynor’s action, imperiously demanded that Governor Fort of New Jersey order out the militia to protect the company there, and complaining against the traffic rules of Jersey City’s police commissioners, designed to keep order.

The official dignity of the commissioner was much ruffled by this action. But it forcibly illustrates the indifferent attitude of the large corporation towards political government. “Serve us er we ignore you,” is their unspoken but implied command. Heads of powerful trusts whose servants sit in Congress, do not take orders from local authorities. Governor Fort, with a weather eye to the election, refused to interfere.

A committee of strike leaders at once visited Mayor Gaynor and he promised to remove the police guards, but a few hours later he issued newspaper interviews denying the labor leaders’ version of his remarks. The police remained.

Immediately among the rank and file of the enthusiastic and outraged strikers sentiment for a general strike rose high. They had the spirit of fight and a strong sense of solidarity. But their craft form of organization, including teamsters of numerous and varied industries, would, in a general tie-up, be taking a slice from each, but crippling none.

It would bring out, for instance, bakery wagon drivers, piano drivers, and cart teamsters, teamsters handling building materials, coach, cab and funeral drivers, etc. While each of these branches would probably be imbued with a firm determination to help win the demands of their fellow unionists, they could not affect the express companies. They are isolated industrially from the scene of action. Nevertheless the idea of 45,000 men in a general sympathetic strike is inspiring as an instance of growing class unity. It served to compel Mayor Gaynor to ostensibly remove the police escort. But mounted officers rode within calling distance.

Simultaneously came the action of the International Association of Longshoremen of 40,000 membership, which notified the steamship companies that they would handle no goods handled by strikebreakers, and furthermore announced to the strikers that they were willing and ready to enter a general strike, when the expressmen said the word. Then the mayor “acted.” He has strangely established a reputation as a fair minded and just man, to the extent of dazzling many radicals, yet his administration has been characterized by indecision and vacillation—as exemplified by his “action.” Ignoring the city ordinance requiring that all drivers be licensed and the fact that none of the strikebreakers had complied with the law, he adopted the pose of conciliator and arbitrator.

The Express Companies had solicited the aid of the Civic Federation and a committee of the latter infamous organization appeared on the scene, including John Mitchell and Tim Healy. “Peace and heart-to-heart talks” was the slogan of the hour. William H. Ashton, organizer of the A.F. of L., is quoted in the New York World of November 3 as standing ready to accept the decision of a board of arbitrators appointed by either the Civic Federation or the Merchants Association, and as saying emphatically, “I will force the strikers to accept such a settlement.” Under the contradictory circumstances of the men talking general strike and war, the leaders talking arbitration and peace, a mass-meeting was held Friday, November 4, in Teutonia Hall. The leaders did the speech-making. Persuasively glib of tongue and tricky in parliamentary procedure, these men, who were anxious to have the differences arbitrated by the companies’ allies and who boasted of their power to force the men to accept such a decision— instigated a motion to postpone further action for one week. Generously they gave the companies time to consider and probably hoped to carry their friends, the Democratic politicians safely over Election Day, while they gained time to head off a general strike among the men. “The general strike is the one thing we do not want to call,” said Mr. Tobin. “It is our last weapon. We do not like to injure innocent business men, but we must fight to the end.”

The strong class feelings engendered by a general strike is not to be desired by “identity of interests” advocates, nor is the further illustration to the rank and file, of the impotency of their present form of organization, which cross-cuts industry but cannot paralyze it.

A further statement to the mass-meeting by this Mr. Tobin, who is President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, is worthy of consideration. He said he was astounded to hear that conditions were so miserable among the teamsters; that men worked for as low as $11 and $12 per week and had no scale of hours. Remarkable, is it not, that the President of a union can publicly declare his ignorance of the wages paid in a cosmopolitan center and not be fired for incompetency?

Insistence upon the part of some wily politician finally compelled the Mayor to commit himself upon the license dispute. He ordered that all drivers apply for licenses and that no unlicensed driver be accorded police protection, this after the guards were supposed to have been removed. If a striker throws a brick he is summarily accorded “police protection”—to the station house. One may venture the pertinent question to Mayor Gaynor, “Why are the unlicensed drivers not arrested for violation of a city ordinance?”

The Board of Licenses is allowed three days to pass upon applications, during which time, were they so disposed, they could compel the applicants to desist from driving, instead of which the law is suspended.

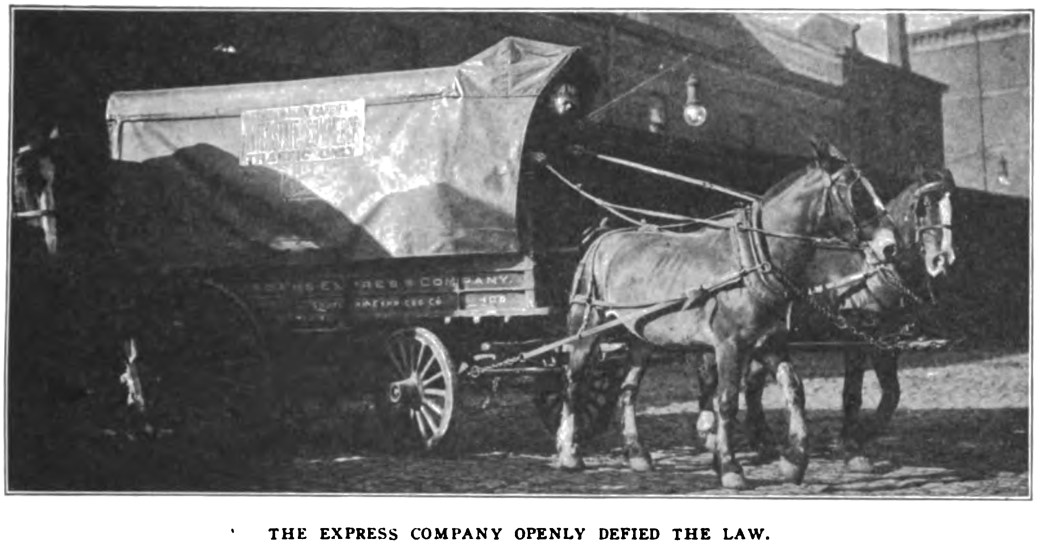

The Express Companies claim immunity from the regulation, under the Interstate Commerce Act. They have signified their intention of contesting its constitutionality and of demanding Federal protection, if their drivers are molested—a pretext to secure regular soldiers. Wagons to deliver goods in New Jersey have been sent out for New York, and the New York deliveries start from Jersey City bearing signs “Interstate Commerce Only.” Thus the law in both states is openly defied.

All day Friday, committees from the strikers waited upon the respective companies and submitted reports to the mass meeting in the following “encouraging” manner. American Company’s—vice-president would “look into the grievances;” Adams Company—‘“all seemed favorable excepting the clause demanding recognition of the union;” United States Company— “progress.”

Saturday afternoon a committee of labor leaders who had hung around Mayor Gaynor’s office all day awaiting a response to their offer to arbitrate, received the following letter:

Hon. W. J. Gaynor, Mayor, New York City.

Dear Sir: Although no demand was made on any express company before the strike except by a small body of helpers of the United States Express Company for an increase in pay, the men will be re-employed in their former positions and at former wages, without discrimination against any because. of having left the service, upon their individual applications made not later than Monday, November 7, 1910.

After resumption of work and without delay each company will confer with its employees and endeavor to arrange wages satisfactory to the men and the company.

Yours truly,

Signed by: Adams, American, National, United States and Wells, Fargo Co.

Thus the extremely mild proposition of the union that “the men shall not be discriminated against for any cause whatsoever except for the use of personal violence during the strike,” was curtly rejected.

The delay has served simply to increase the impatience of the men, as has the death of one of their number, Peter Roach, who was shot by a strikebreaker, and they are at date of writing (November 10), clamoring for a general strike. They have been joined by nearly 2,000 chauffeurs and cab drivers, who are out not only in sympathy with the expressmen but to demand a weekly wage of $17.50 and a twelve-hour day, also abolition of the rule holding them responsible for damages to the-machines. Detectives at once invaded their hall and searched closets and desks for firearms. If the same degree of officiousness had been displayed in searching strikebreakers, Peter Roach would not have been murdered.

There is, of course, much opposition displayed towards the strikers on the part of the press. Some of New York’s wise economists have prophesied that if the strikers win their fight the express companies will immediately raise the rates and pass the weight of the increase along to the pocketbooks of the public. Perhaps so, but it convicts the companies of being mighty poor business men. It would be strange indeed if there were loose change in the pockets of the “poor, dear public” that the express corporations wait for a strike as a pretext to extract! Why wait till the day after the strike? Why not increase the rates the day before, to finance the fight against it?

But why should they oppose a strike under such circumstances? Rather would they say “Go ahead, boys. The public will foot the bill.”

Surely one cannot explain away their aggressive attitude by assuming that they do not want the strikers “to get the habit.”

Mr. Samuel Gompers appeared on the scene for a few days and in co-operation with Tobin and others used his good offices to settle. “I still hope for a settlement so that a general strike may be escaped,” he said on November 8.

Mr. Tobin, before leaving for St. Louis, anxiously solicited the appointment of an “honest and impartial board’’—this after the Philadelphia arbitrator, decided in favor of the street-car men who had not left the company’s employ during the trouble, viz., the gallant battle of last February.

Wm. Ashton, who is now in complete control, announces this morning (November 10) that the Executive Committee’s decision on’ the matter of a general tie-up is to be postponed another forty-eight hours, at the request of the State Board of Mediation and Arbitration. This postponement from day to day has continued now for over a week. The general strike will not occur if the leaders can avoid it. After the gage of battle has been thrown in their teeth by the companies these “brotherly love” unionists solicit further conferences—will do anything but fight.

Meanwhile the men have been joined by the Fifth avenue stage drivers, by the coal drivers and by the ice-cream drivers. They continue to clamor for a general strike and as Mayor Gaynor has issued orders to impound all wagons without licenses, the men are in an excellent strategic position to win.

Here’s success to these brave fighters, the men who, misled and bewildered, still demand concerted action. May they gain their shorter hours, high wages and ultimately their freedom from labor leaders and wage-slavery!

LATER: Word has just been received that the expressmen’s strike was “officially” ended November 12. The Jersey City strikers voted to accept the agreement of the companies, which was accepted by the New York strikers on Thursday night and which the Jersey City strikers rejected on the 11th.

Conditions had reached a point in Greater New York and the surrounding places when a general strike could have been called at the drop of the hat. The workers could have completely paralyzed the industry of that part of the country, but William Ashton, General Organizer of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, leader of the strike and a Tammany Hall politician, checked the tendency for a general strike. He got the men to agree to a postponement of the strike for one week. This broke the back of the strike. On November 11 a proposal submitted to the men and cooked up by Mayor Gaynor, President Towne, of the Merchants’ Association, and Ashton offered a “provisional agreement” and was finally run through. The strike “leaders” were all on the side of the express companies and most flagrantly sold out the men. ‘They divided them; distracted them; rushed them, and the whole strike fizzled out because the men trusted to “leaders” to carry on the battle. The men who had refused to sign the agreement were between the Devil and the Deep Sea—the leaders, the men who had signed and Mayor Gaynor who threatened to put two policemen on each wagon. There was nothing for them to do but to yield.

Comrade Louis Duchez says: “It seems to me that it was a good thing for the cause of industrial unionism and class action. The men cannot lie down because the same pressure is behind and they will know better than to trust “labor leaders” the next time. They know they cannot trust to city ordinances requiring scabs to hold licenses. They know that policemen will be used to take their places. They will become revolutionary. They will learn to trust only in themselves.”

The International Socialist Review (ISR) was published monthly in Chicago from 1900 until 1918 by Charles H. Kerr and critically loyal to the Socialist Party of America. It is one of the essential publications in U.S. left history. During the editorship of A.M. Simons it was largely theoretical and moderate. In 1908, Charles H. Kerr took over as editor with strong influence from Mary E Marcy. The magazine became the foremost proponent of the SP’s left wing growing to tens of thousands of subscribers. It remained revolutionary in outlook and anti-militarist during World War One. It liberally used photographs and images, with news, theory, arts and organizing in its pages. It articles, reports and essays are an invaluable record of the U.S. class struggle and the development of Marxism in the decades before the Soviet experience. It was closed down in government repression in 1918.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/isr/v11n06-dec-1910-ISR-gog-Corn-OCR.pdf