The public addresses by Marx on the Franco-Prussian War and the Civil War in France in the name of the International are duly famous. Here, in a very different tone, Marx reports to the 1872 Hague Congress of the International (not attended by Marx, but read there) on the aftermath of the Commune and the consequences for the International itself.

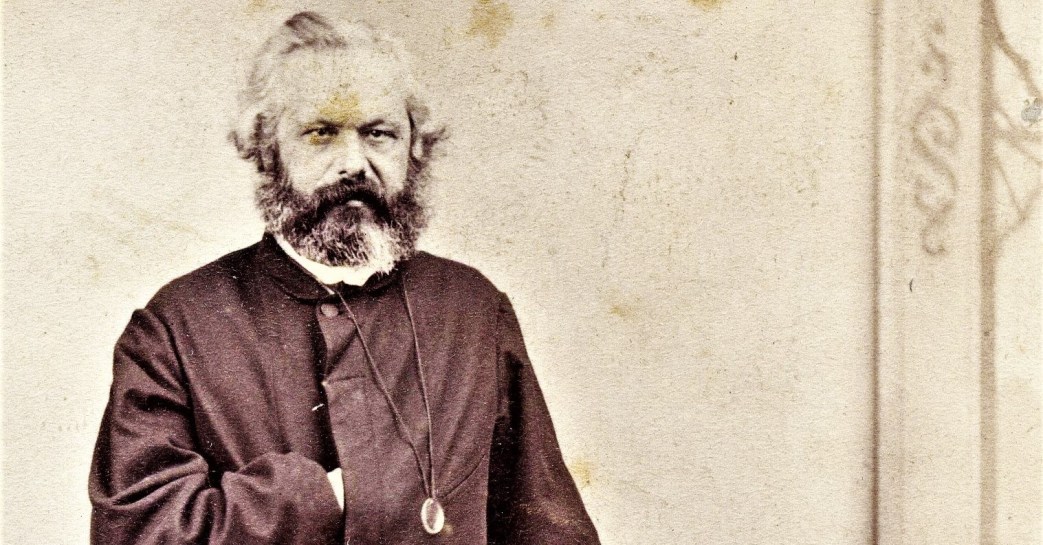

‘Report of the General Council’ (1872) by Karl Marx from Communist International. Vol. 10 No. 5-6. March 14, 1933.

Read at the Public Session of the International Congress.

The Hague, September 6, 1872.

Workers,

Since our last Congress in Basle two great wars have changed the aspect of Europe–the Franco-German war and the civil war in France; a third war preceded both these, accompanied them and has been continued after them–the war against the International Working Men’s Association.

The Paris members of the International had publicly and expressly told the French people: to vote for the plebiscite means nothing but voting for despotism in the inner affairs of France, and for war abroad. They were arrested on the eve of the plebiscite, on April 29, 1870, under the pretext of participation in a conspiracy, which was said to have been hatched for the purpose of murdering Louis Napoleon. Simultaneous arrests of members of the International took place at Lyons, Marseilles, Brest, and in other towns. In its declaration of May 3, 1870, the General Council said: “This last conspiracy is a fitting match to its two predecessors of grotesque memory; the noisy methods of violence resorted to by the French government can have no other object than the successful manipulation of the plebiscite.” We were right. We can now see from the documents which, after the collapse of the December government, have been published by its successors, that this last plot was woven by the Bonapartist police themselves. In a superb circular which Ollivier sent to his agents a few days before the plebiscite, he actually wrote as follows:–“The leaders of the International must be arrested; otherwise the plebiscite cannot be a success.” After the plebiscite comedy was over, however, the members of the Paris Federal Council were condemned by Louis Bonaparte’s judges merely for their participation in the International, and not for being concerned in any alleged conspiracy. The Bonapartist government thus found it necessary to usher in the most disastrous war which has ever befallen France by a preliminary campaign against the French sections of the International Workingmen’s Association. Let us not forget that the working class of France arose like one man to reject the plebiscite. Nor let us forget that the Stock Exchanges, the Cabinets, the ruling classes, and the press hailed the plebiscite as a brilliant victory of the French imperial power over the French working class. (Address of the General Council on the war, dated July 29, 1870.)

A few weeks after the plebiscite, when Bonapartist press was beginning to kindle bellicose instincts among the French people, the members of the Paris International, undaunted by the persecution of the government, issued their appeal of July 12 to “The Workers of All Nations, in which they denounced the intended war as criminal folly, told their brothers in Germany that “their division would result only in the complete triumph of despotism on both sides of the Rhine,” and declared: “We, the members of the International, know no national boundaries.” Their appeal met with an enthusiastic echo in Germany, so that the General Council could say with justice in its manifesto of July 23, 1870: “The very fact that in the precise moment when official France and official Germany were hurling themselves into a fratricidal war, the workers of France and Germany sent messages of peace to one another—this great fact, unexampled in the history of the past, shows that in contrast to the old world with its social misery and its political madness, a new society is growing up which will have no other foreign policy than that of peace, because it knows no other home policy than that of labour. Those who are paving the way for this new society are the members of the International.” The members of the Federal Council remained under lock and key until the proclamation of the Republic. Meanwhile the other members of the Association were daily denounced before the mob as Prussian spies. With the capitulation of Sedan the Second Empire ended as it had begun, with a parody; and at that moment the Franco-German war entered upon its second stage. It became a war against the French people. After all its solemn declarations that it was only taking up arms to ward off foreign attack, Prussia now threw off the mask and proclaimed a war of conquest. From now on it found itself obliged to fight not only against the Republic in France, but simultaneously against the International in Germany. We can here only indicate course of this struggle. Immediately after the declaration of war the greater part of the territory of the North-German League–Hanover, Oldenburg, Bremen, Hamburg, Brunswick, Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg, Pomerania, and the Province of Prussia–were placed under a state of siege and delivered over to the tender rule of General Vogel von Falkenstein. This state of siege, which was proclaimed as a means of protection against invasion threatening from without, immediately changed into a state of war against the members of the German International. On the day after the proclamation of the republic in Paris, the Brunswick Central Committee of the German Social-Democratic Workers’ Party, which formed section of the International within the barriers imposed by the national laws, issued its manifesto of September 5. It called upon the workers to oppose with all their might the dismemberment of France, and to demand an honourable peace for France and the recognition of the French Republic. The manifesto declared the intended annexation of Alsace-Lorraine to be a crime, the consequences of which would be to transform all Germany into a Prussian barracks and to make war a European institution. On September 9 Vogel von Falkenstein had the members of the Brunswick committee arrested and conducted in chains a distance of 130 German miles to Lötzen, a Prussian fortress on the Russian frontier, where their shameful treatment served as a fitting counterpart to the magnificent reception of the imperial guest at Wilhelmshöhe. As imprisonment, banishment of workers from one German state into another, suppression of workers’ newspapers, military brutalities and police chicanery of every kind did not keep the International vanguard of the German working class from acting in the spirit of the Brunswick manifesto, Vogel von Falkenstein, in a decree of September 21, prohibited all meetings of the Social-Democratic Party. On October 5 this prohibition was revoked by a second decree in which he cunningly commands his police spies personally to report to him all individuals who by public demonstrations may encourage France in its resistance to the peace conditions imposed by Germany, in order that he may keep such keep such people from mischief during the duration of this war. Leaving the cares of the war abroad to his Moltke, the King of Prussia gave a new turn to the war at home. On October 17, he dispatched an order in Council from Versailles to Hanover that Vogel von Falkenstein should temporarily transfer his Lötzen prisoners to the Brunswick district court, which court on its part must either find legal grounds for their arrest or deliver them back into the safe keeping of the terrorist general.

Vogel von Falkenstein’s disciplinary measures were, of course, imitated throughout the whole of Germany, while Bismarck in his diplomatic circular irritated Europe by coming forward as an indignant champion of the right of free speech and of free right of assembly for–the peace party in France. At the very time when he was demanding a freely elected National Assembly for France, he had Bebel and Liebknecht arrested in Germany as punishment for having upheld the International in opposition to him in the North-German Parliament, and with the object of preventing their reelection at the coming elections.

His lord and master, Wilhelm the Conqueror, gave him support with a new order in Council from Versailles which prolonged the state of siege, i.e., the suspension of all bourgeois right for the whole period of the election. In actual fact he maintained the state of siege in Germany until two months after the conclusion of peace with France. The obstinacy with which he insisted upon the state of siege at home, and his repeated personal interference against his own German prisoners prove that even amid the rattle of triumphant arms and the fanatical jubilation of the entire German bourgeoise, he is frightened of the growing party of the proletariat. This was an involuntary gesture of homage from material force before moral strength.

If the war against the International had hitherto been localised–first in France from the days of the plebiscite until the fall of the empire, afterwards in Germany during the whole period of the republic’s resistance against Prussia–it became general from the setting up of the Paris Commune and after its fall.

On June 6, 1871, Jules Favre issued his circular to the foreign powers demanding that the members of the Commune be handed over as common criminals, and appealed for a crusade against the International as the enemy of the family, of religion, of order, and of property–so aptly represented in his own person. Austria and Hungary immediately took up the cue. On June 13 a police raid was started against the alleged leaders of the Budapest workers’ union. Their papers were confiscated, and they themselves arrested and prosecuted for high treason. Various delegates of the Vienna International, just then paying a visit to Budapest, were taken off to Vienna for further proceedings against them. Beust asked for and received from his parliament an additional sum of three million gulden “for expenditure on political information which, as he complained, had become more indispensable than ever as a result of the dangerous expansion of the International over the whole of Europe.” From this time on the working class in Austria-Hungary were subjected to a veritable reign of terror. Even in its last death agonies the Austrian government still clings with the strength of despair to its old prerogative of playing the Don Quixote of European reaction.

A few weeks after the circular of Jules Favre, Defaure laid before his chamber of Junkers, a law, which has now come into force, according to which it is a crime to belong to the International Working Men’s Association, or even to share its principles.

As a witness before the Junker commission on Defaure’s proposed measure, Thiers boasted that the law had sprung from his own ingenious brain. It was he, he said, who first discovered the infallible panacea that the International must be treated in the way in which the Spanish Inquisition treated heretics. But even in this point his claim to originality will not bear examination. Long before he was ordained the saviour of society the Vienna law courts had already laid down the real jurisprudence which members of the International might expect at the hands of the ruling class. On July 26, 1870, the most prominent men in the Austrian workers’ party were condemned for high treason to several years of severe imprisonment with one day of liberation per month. The grounds for the sentence were as follow:–

“The prisoners themselves admit that they have adopted the programme of the German Workers’ Congress at Eisenach (1869) and acted in accordance with it. This programme includes the programme of the International. The aim of the International is to emancipate the working class from the rule of the possessing classes and from political dependence. This emancipation is incompatible with the existing institutions of the Austrian State. Thus, whoever accepts and spreads the principles of the programme of the International, is committing an action calculated to cause the overthrow of the Austrian government, and is therefore guilty of high treason.”

On November 27th, sentence was passed on the members of the Brunswick Committee. They were punished with terms of imprisonment of varying length. In giving grounds for its sentence, the court referred expressly to the reasons given for the Vienna sentence as though referring to a legal precedent.

At Budapest the accused from the workers’ union, after suffering for nearly a year the same shameful treatment as that to which the British government had subjected the Fenians, were brought before the court on April 22, 1872, Here the public prosecutor demanded that the same jurisprudence be applied as had been established at Vienna. The court, however, acquitted them.

In Leipzig on May 27, 1872, Bebel and Liebknecht were sentenced to two years’ confinement in a fortress for action calculated to cause high treason.

The reasons given for this sentence were the same as those in the Vienna verdict. Only in this case the jurisprudence of the Vienna judges was backed up by the vote of Saxon jurymen.

In Copenhagen the three members of the General Committee, Brix, Pio, and Geleff, were arrested on May 8 this year; they were arrested because they had declared their firm resolve to hold an open-air meeting despite police orders to the contrary. After their arrest they were told that socialist ideas are in themselves incompatible with the existence of the Danish state, and that therefore the mere spreading of these ideas is tantamount to a crime against the Danish constitution. Once again the jurisprudence of the Vienna law court. The accused are still under arrest awaiting preliminary examination.

The Belgian government, favourably noted for its sympathetic answer to Jules Favre’s demand for extradition, hastened to lay before its Chamber of Deputies, through the hand of Malou, a hypocritical reprint copy of Defaure’s law.

His Holiness Pope Pius IX. said in an address to a deputation consisting of Swiss catholics: “Your government, which is republican, deems itself obliged to make a severe sacrifice for what is called freedom. It grants rights of sanctuary to a number of people of the most evil sort; it suffers that sect of internationals who should be treated by all Europe as Paris has treated them. These gentlemen of the International, who are not gentlemen at all, are to be feared because they are working in the service of the eternal enemy of god and mankind. What is to be gained by protecting them? One should pray for them.”‘ Hang them first and pray for them afterwards!

Supported by Bismarck, Beust and Stieber, the emperors of Austria and Germany, met together in Salzburg in September, 1871, to found a holy alliance–so-called–against the International Workingmen’s Association: “Such a European alliance,’ declared Bismarck’s private Moniteur, the Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung, “is the only possible salvation of the state, of the church, of morality, in short of everything which constitutes European states.” Bismarck’s real aim was, of course, to assure himself of alliances for a future war with Russia, and the International was held up before the eyes of Austria merely as a red rag is held up before a bull.

Lanze suppressed the International in Spain with a simple decree. Sagesta declared it to be outlawed in Spain; he hoped, perhaps, in this way to put himself on a better footing with the English money market.

The Russian government, which, since the emancipation of the serfs, has been reduced to the dangerous expedient of making timid concessions to the popular clamour one day and withdrawing them again the next, found in the general hue and cry against the International a pretext for the intensification of reaction at home. Abroad, it had hope of probing into the secrets of the association. It did, in fact, succeed in finding a Swiss judge who, in the presence of a Russian spy, conducted a search of the apartment of Outines, a Russian member of the International, and former editor of the Geneva paper Egalité, the organ of our Swiss Latin section. Even the republican government of Switzerland was only prevented by the agitation of the Swiss International from delivering up refugees from the Commune to Thiers.

Finally, the government of Mr. Gladstone, being unable to interfere in Great Britain, at least proved its goodwill by the police terrorism which it exercised in Ireland against our section then in the process of formation, and by the orders it gave to its representatives abroad to collect information relating to the International.

However, all measures of repression which the ingenuity of various European governments could devise, pale before the campaign of slander which was launched by the lying power of the civilised world. Apocryphal stories and secrets of the International, shameless forgery of public documents and private letters, sensational telegrams, etc., followed fast upon one another; all the floodgates of calumny which the mercenary bourgeois press had at its disposal, were suddenly thrown open, and let loose a cataclysm of defamation designed to engulf the hated foe. This campaign of calumny does not possess its match in history, so truly international is the scene on which it is enacted, and so complete is the agreement with which the most various party organs of the ruling classes conduct it. After the great fire in Chicago the news was sent round the world by telegraph that this fire was the hellish act of the International, and, indeed, it is to be wondered at, that the hurricane which laid waste the West Indies was not ascribed to this same satanic influence.

In previous public annual reports the General Council has customarily given a review of the progress of the association since the previous congress. You, workers, will respect the reasons which lead us to make an exception in this case. Moreover, perhaps the reports of the delegates from the various countries– they know best how far they can go–will perhaps make good this defect. We will confine ourselves to saying that since the Basle Congress, and especially since the conference held in London in September, 1871, the International had gained ground among the Irish in England and in Ireland itself; in Holland, Denmark, and Portugal, that it has firmly organised itself in the United States, and that branches exist in Buenos Aires, Australia, Australia, and New Zealand. The difference between a working class without an International and a working class with an International Association is most strikingly shown if we look back to 1848. It took many years before the workers themselves recognised the work of their own champions in the June insurrection of 1848. The Paris Commune was immediately acclaimed with delight by the proletariat of all countries.

You, the deputies of the working class, meet together in order to consolidate the militant organisation of a league whose aim is the emancipation of labour and the extirpation of national struggles.

Almost at the same moment the crowned dignitaries of the old world are meeting together in Berlin to forge new chains and hatch new wars.

Long live the International Workingmen’s Association!

The ECCI published the magazine ‘Communist International’ edited by Zinoviev and Karl Radek from 1919 until 1926 irregularly in German, French, Russian, and English. Restarting in 1927 until 1934. Unlike, Inprecorr, CI contained long-form articles by the leading figures of the International as well as proceedings, statements, and notices of the Comintern. No complete run of Communist International is available in English. Both were largely published outside of Soviet territory, with Communist International printed in London, to facilitate distribution and both were major contributors to the Communist press in the U.S. Communist International and Inprecorr are an invaluable English-language source on the history of the Communist International and its sections.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/international/comintern/ci/vol-10/v10-n05-n06-mar-14-1933-CI%20grn-riaz-OC.pdf