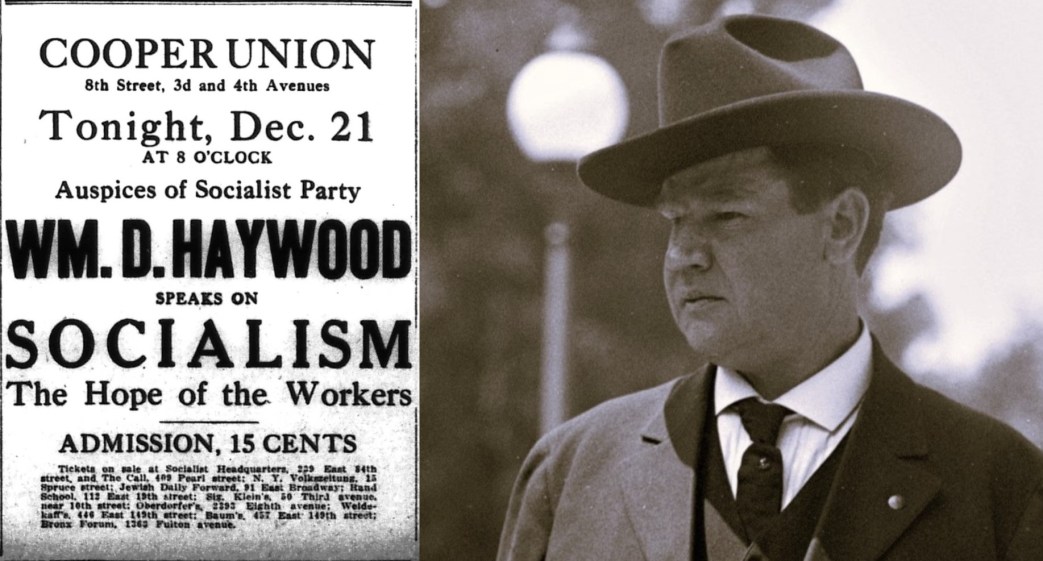

Campaigning for a seat on the Socialist Party’s National Committee as part of a larger organizing of the left wing, the ‘industrial socialists,’ Haywood brings his revolutionary, emancipatory proletarian message to the intellectual home of the Party’s right wing in a barn-burner at Cooper Union on December 21, 1911. Justus Ebert reports.

‘Revolter Haywood Stirs the Pot’ by Justus Ebert from Revolt (San Francisco). 2 No. 31. January 27, 1912.

The evening of December 21, 1911, was an interesting one in little old New York. Wm. D. Haywood held forth at historic Cooper Union on “Socialism, the Hope of the Workers,” under the auspices of the Socialist Party.

Haywood and his policy is just now the subject of a vigorous discussion within the Socialist Party. He has the hardihood to stand for a socialism that is industrial in character rather than political and that lives the class struggle more than it talks about and theorizes over it. In fact, Bill is an experienced workingman; not a lawyer nor a clergyman asking to get office, power or an income, on the backs of the working class.

Haywood, at the very outset, made it plain that it is his opponents and not himself who have the wrong end in this controversy.

He said that to read some of the definitions in the current discussions in the Socialist press one would think that Socialism was a chop suey clothed in a mysticism that would baffle the brains of a Chinese mandarin to understand.

He cautioned his hearers against thinking of Socialism as something having to do entirely with halls of legislature, congress and political office. He advised them to think of it as having to do with the shop. He said: “Turn your mind inward and think of the machine where you are employed every day.” He also urged his hearers to think of their individual, group and social relations, defining each in their turn.

Then Haywood proceeded to define Socialism. He said he had no doubt that it would be so clear that the intellectuals would ask him to define his definition. But he said the definition would be clear to the working class.

Under Socialism the workers will need no passports, nor citizen papers. They would pass from industry to industry, regardless of territorial and political boundaries, and would enjoy rights because of their industrial value to society. Socialism is industrial democracy, and industrial democracy is Socialism.

It is only on the industrial basis that every worker can organize, man, woman or child, regardless of race, color or creed, be he or she Anarchist, Socialist, Democrat or Republican. Industrialism means complete working class unity.

“Under Socialism,” said Bill, “the worker will not be the subject of a State, but a free man in the industry where he is employed.”

“We do not,” he said further, “have to go out of the shop to inaugurate Socialism. We do not need to climb the heights of Utopia, where you will receive $4 a week pension after you are 60 years of age. Socialism is in a measure with us now in the shop, and there’s the place to inaugurate it.

“With the success of Socialism,” contended Haywood, “practically all the political offices of the present day will be put out of business.” While he was not opposed to political action, he considered it decidedly better for the workers to elect a superintendent in some branch of modern industry than to elect a Socialist to Congress.

Under Socialism we shall not have Congress. Our Congress will not be filled by aspiring lawyers without practice and ministers without congregations. It will be a gathering of expert workers, whose duty it will be to administer industry in the interests of all.

The Class Struggle.

Following the foregoing presentation of Socialism, Haywood next took up the class struggle–the war between the capitalist class and the working class–is to Haywood the key to correct tactics and victory. He said: “There never was a time in all the history of the world when the working class was not dominated by tyrants. There never was a time so tyrannical as now.”

The workers have been slaves, serfs, chattel slaves, and wage slaves. They are now being devoured by the Frankenstein of their own creation; the machinery which their own inventive and constructive genius has given to the world. This machinery creates a thousand fold more wealth than 50 years ago. The army of the unemployed increases in all branches of industry, due to the marvelous machines which they have created for their own oppressors, who control them.

The class struggle is the basis of Socialism. There is a necessity for emphasizing the class struggle. When the workers understand the class struggle victory will be theirs. He would make the class struggle so clear that even a lawyer could understand it. “You can not see the class struggle through the stained window glass of a cathedral, or through the law books of the capitalist class.

“To understand the class struggle you have to go into the shop, ride on the top of a box car or under it; you must go with me into the iron mills or into the bowels of the earth, 2,700 feet or more below the surface, and with only the flicker of a miner’s lamp to light up the surrounding darkness.

“The class struggle is the effort of the working class to wrest from the capitalist class the product of its toil.

“The class struggle will continue so long as a privileged few exist at the sacrifice of the many.”

Stands by the McNamaras.

Haywood declared that the men that were in the Los Angeles jail knew what the class struggle is the 120 arrested picket law violators and the McNamaras.

“While the capitalist class,” declared Haywood, is writing the record of the crimes of the Structural Iron Workers, it is not a part of the duty of the Socialists to assist them. It is their duty to pile up high the record of the infamies of the capitalist class.”

(Long continued applause and cries of “That is impossible.”)

“For my part,” shouted Haywood, “I shall always be a defender of the working class, no matter how accused. Knowing, as I do, the infamies of capitalism, my heart is with the McNamaras in jail.”

(Great applause.)

“Let the capitalists bury their own dead. Let them bury the 21 killed in Los Angeles. We will bury our dead; the 250 miners killed in Briceville, Tenn.”

(More vigorous applause.)

Haywood contrasted the haste with which Federal juries seek to bring indictments against the Structural Iron Workers and the official indifference manifested in the Briceville horror. He then drew a picture of the 700,000 workers who are annually killed and injured in preventable accidents, because it would interfere with profits, and human life is cheaper than safeguards a slaughter that is permitted to go on without any attempt at legal interference.

“Until we have attained a condition whereby we can protect ourselves,” declared Haywood, “I can not find it in my heart to condemn the McNamaras.”

Haywood showed that the class struggle is not only domestic, but world-wide in character. He drew a panoramic sketch of it all over the world: “Bloody Sunday,” in Russia: the Finnish struggle against the autocracy of the czar; the Swedish general strike; the Spanish general strike: the miners’ strike in Wales, and the recent English general strikes. Each and every episode yielded a lesson for the working class.

A Constructive Program.

Haywood again returned to the constructive program of Socialism, as he conceives it; which is the organization of the workers within industry to own and control industry.

He took up and demolished the futility of the remedies suggested by the non-industrial and pro-political Socialists, viz: Confiscation, competition, compensation, conversion and coercion. Of confiscation he said:

“I like that word; it suggests stripping the capitalists of their holdings. But it needs power. Back of the capitalists are the State, militia, police, etc. Only the power of an industrially united working class can overcome them.”

Competition he regarded as impossible. “It may be likely to build competing shops against capitalists. But it is impossible to build another Niagara Falls to generate power to run them. Or to create another coal bed, to get fuel for the same purpose. In other words, the capitalists control the essentials of competition, without which it is bound to be a failure.”

Compensation was out of the question. It would relieve the capitalists of responsibility and, at the same time, make an interest-bearing bond-holding aristocracy of them.

Conversion was a joke. “The Christian Socialists (who propose it) are, said Haywood, “drunk on religious fanaticism and trying to sober up on economic truth.”

Coercion met with Haywood’s favor. “I like that,” said he. “I believe in the strike; in the boycott; in coercion.” Then he proceeded to show how coercion is made impossible by craft organization. He used his hand as an illustration, showing how each of his fingers and his thumb were independent members that could be brought and made to act together in his closed fist. “Now,” said he, “imagine myself tying this big finger up tight with a rag called contract. Why, it would stand erect and prevent me from closing my fist. It would decay and become useless. So with craft unionism.” “Industrialism,” Haywood contended, “was constructive and defensive organization at one and the same time. Laws can not be made quick enough to cover the changes made by the machine. The workers must organize to administer industry as conditions arise. The working class had better not be organized at all as to be organized as it is at present.”

“The scab of the future,” says Haywood; ‘will be the man who will leave the job; not him who takes it.”

In conclusion, Haywood shouted:

“Our purpose is to overthrow capitalism; by peaceful means if possible; by forcible means if necessary.”

Revolt ‘The Voice Of The Militant Worker’ was a short-lived revolutionary weekly newspaper published by Left Wingers in the Socialist Party in 1911 and 1912 and closely associated with Tom Mooney. The legendary activists and political prisoner Thomas J. Mooney had recently left the I.W.W. and settled in the Bay. He would join with the SP Left in the Bay Area, like Austin Lewis, William McDevitt, Nathan Greist, and Cloudseley Johns to produce The Revolt. The paper ran around 1500 copies weekly, but financial problems ended its run after one year. Mooney was also embroiled in constant legal battles for his role in the Pacific Gas and Electric Strike of the time. The paper epitomizes the revolutionary Left of the SP before World War One with its mix of Marxist orthodoxy, industrial unionism, and counter-cultural attitude. To that it adds some of the best writers in the movement; it deserved a much longer run.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/revolt/v2n31-w40-jan-27-1912-Revolt.pdf