Written shortly before her death Eva Goldbeck, wife of avant-garde composer Marc Blitzstein, looks at the work of Bertolt Brecht and his Lehrstuecks,“teaching-plays.”

‘Brecht and the Principles of “Educational” Theater’ by Eva Goldbeck from New Masses. Vol. 18 No. 1. December 31, 1935.

MOTHER, a play by Bert Brecht with music by Hanns Eisler, was recently produced as the fifth offering of the Theater Union.

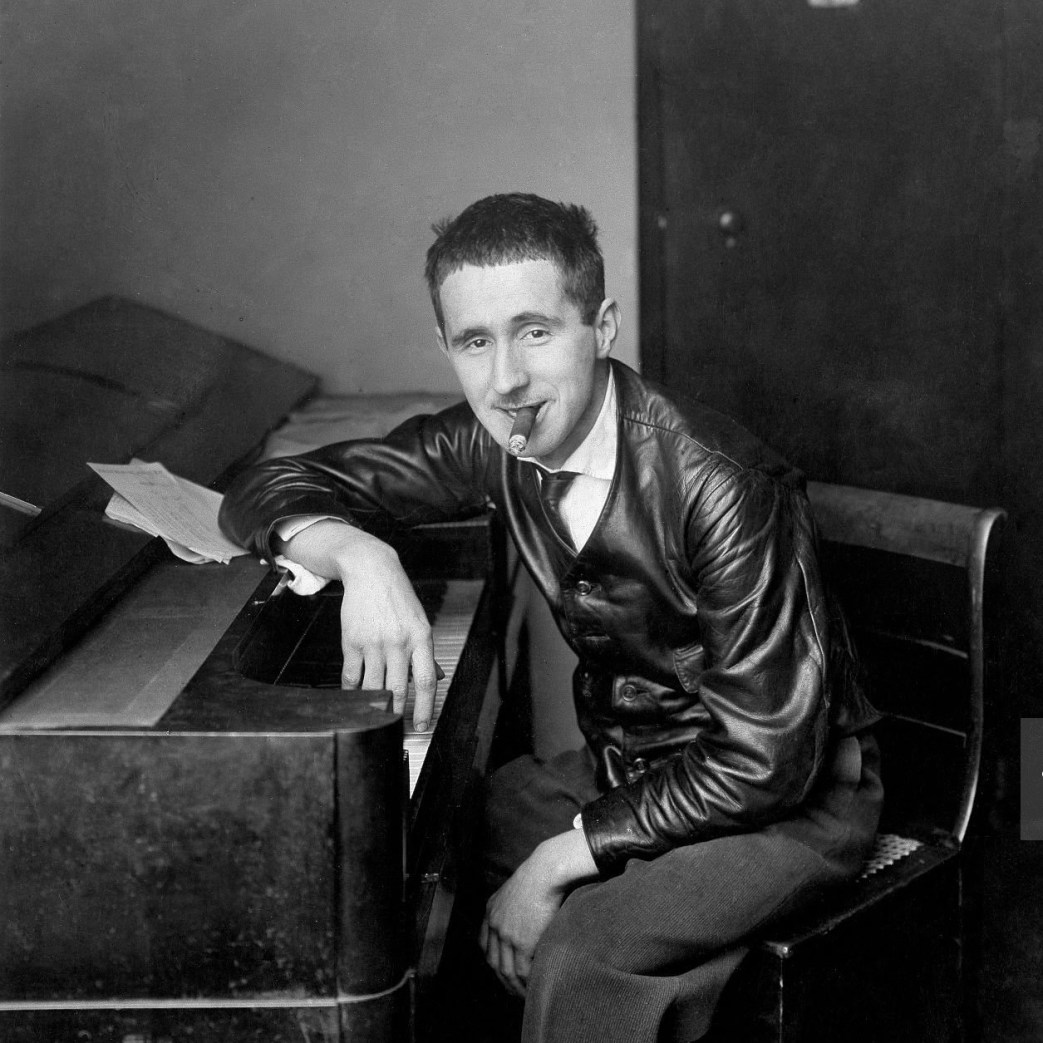

In the late 1920s Brecht introduced the Lehrstueck and revolutionized the German theater; Eisler’s mass-songs made him the foremost proletarian composer of Central Europe. Now Eisler is “the most forbidden composer in the world”; Brecht is the most popular “underground” writer in Hitler’s Reich.

Both men started out with a German upper-middle-class background and academic training. Both became artists with a scientific approach and a practical psychology. Eisler drew his political, and hence his artistic, conclusions from the war. He found that the twelve-tone system devised by his teacher, Arnold Schoenberg, was like a wall at the end of a centuries-old road in music; and he turned from the Schoenbergian Sprechstimme (“Speech-singing”) to the voice of the masses. Almost fifteen years ago a strike in Leipzig was kept going by a house-to-house serenade with a song by young Hanns Eisler; and when Hitler came to loot Germany, there were records and sheet-music by the thousand of Eisler’s mass-songs to be smashed and burned. In Brecht’s case, his artistic development brought about his political education. He began as a “thinker,” but later he wanted to write an educational drama about wheat and his investigation of the wheat industry inevitably took him “from Hegel to Marx.” That road logically led out of Germany, on the morning after the Reichstag fire. (Early this year a pamphlet by Brecht, “Five Difficulties in Writing the Truth,” was published; and now he has been expatriated “because of low-mindedness.”)

Fundamentally Brecht and Eisler are teachers. What can we learn from them? Brecht’s first play, Drums in the Night, won the Kleist Prize for drama given by the German State but it was a satire on the petty-bourgeois liberalism that took credit for the revolution of 1918 and its literary glorification. Neither the vague idealism nor the naturalistic and expressionistic dramaturgies that dominated the German theater at the time seemed practical to Brecht. He wanted to work out “small models for the stage” to show how people could live and act better. He also wanted to write good plays: but for him how “good” a play was depended on its use to the audience, not on its value to the author. Gaining practical experience as régisseur at Max Reinhardt’s famous Deutsches Theater, Brecht undertook a scientific research of the world’s dramatic literature and systematically wrote copies of Greek, Elizabethan, Spanish and Chinese plays. He found the Chinese “static” drama the most. nearly related to his own conception; and the Aristotelian drama, the basis of our western dramatics, the most antithetical. The object of the Greek drama is to make the spectator identify himself with the character and go through” his experiences. Brecht’s educational drama is in direct contrast to this; he calls it the “non-Aristotelian drama” and its methods of production the “epic theater” or “narrative theater” (for the way in which we read a book, thinking things over, is the way we are to see these plays). The object of the drama of education is to make the spectator compare himself—not identify himself–with the characters, to make him observe them as an interested outsider. Significantly, the most fully-developed and popular form of this new dramaturgy is called “study-play” (Lehrstueck, literally, “teaching-play”).

The emotional excitement that is always present in the theater is of course not ignored; but it is minimized and used not to obscure but to clarify the intelligence. Whereas the old theater tries to get below the level of the mind and to use brute emotional force on our subconsciousness, the epic theater tries to make our own reason awaken and direct our emotions. The difference in emphasis and method is dictated by the difference in purpose. The theater of entertainment, though provoking a show of excitement, really keeps us passive; the theater of education wants us to remain as calm and collected as possible, in order to rouse us to ultimate action. Brecht calls the theater as we know it “the trance theater,” for the methods employed to obtain an illusion are everywhere the same-whether water is turned into wine or you or I become Hamlet–and they are the methods of hypnotism: suggestion on the part of the hypnotizer, imitation on the part of the subject. In Shakespeare’s drama, the spectator “becomes” Hamlet, or feels as if he did; in Brecht’s adaptation of Shakespeare (he has adapted Hamlet and Macbeth for the radio), the spectator remains himself and really “sees” Hamlet. When he leaves the theater, he is no longer Hamlet–the illusion has gone; but he is still the man who criticized Hamlet, on the strength of his own experience of life, and thus widened his knowledge. The drama has become an object-lesson.

The chief agent in any theater is of course the actor. In the ordinary theater, he is both medium and hypnotizer. It is he who first identifies himself with the character. He acts as if he were Hamlet: that is, he goes through the motions of what Hamlet does. “Fascinated” by a performance, seeing gestures that “impress” us, we subconsciously copy them; and doing what Hamlet does, we become “absorbed” in him. In the epic theater, on the other hand, the actor does not identify himself with the character but interprets him, both as actor and as critic. In the way he does what the character does, he “suggests” what he himself thinks about it. (The “power of suggestion” is used here, too; but there is a difference between a seance and a debate.) He is a kind of narrator and his method changes according to the requirements of the story he has to tell. Sometimes he only reports a background of action (as in the strike-scene of Mother) or gives an undisguised explanation of a character. (Whereas in the realistic play things have to be explained “naturally,” here the actor can walk right in and say, “I am John Smith, an engineer, forty-two years old.”) Sometimes he identifies himself with a character, thus supplying the “inside,” subjective viewpoint. Sometimes he comments in the very process of “going through” a scene, sometimes he acts it out precisely: but even then he always re-enacts for purposes of illustration, rather than acting as though it were taking place then and there. In the drama as object-lesson, the actor becomes the illustrator; his motions give point to the talk.

The first production of the epic theater, in 1928, was The Three-Penny Opera, adapted from John Gay’s eighteenth-century musical comedy by Brecht, with music by Kurt Weill–a rarely equaled “satiric” success. At about the same time Piscator made his celebrated production of The Good Soldier Schwejk, readapted for him by Brecht; and the two men who had “revolutionized” the German theater were widely acclaimed. The production of Mother in 1931, however was suppressed after seven weeks of success with the new working-public and the still-democratic bourgeois audiences; and Brecht’s Saint Joan of the Stockyards, an example of the spectacle-play in the epic theater, which was accepted by many theaters in 1932, was forbidden even before it appeared.

The big Berlin music week of 1930 brought the premiere of The Standard (Die Massnahme), a study-play for workers’ choruses with text by Bert Brecht and music by Hanns Eisler. This work, which might be called a “platform-opera,” was the first that carried the principles and methods of the epic theater into the operatic field on a grand scale. In the study-play, as in our “agit-prop” play, it is always the lesson that occupies “the center of the stage”; but the form can be adapted to any field of production, dramatic or musical or musical-dramatic, to schools, movies, radio as well as the theater. For the epic theater not only uses all the arts much more than the ordinary theater does, but it combines various forms of production that we have been accustomed to keep separate (we do not even refer to opera as “the theater”). This breaking down of old barriers is perhaps its most “upsetting” aspect for the public. And in contrast to the fusion of the arts that has been attempted by our musical theater–most ambitiously and confusedly in Wagnerian opera–the new synthesis, is based on a “dissociation of elements. In the theater with which we are familiar, a particular production is dominated entirely by one art; the other arts are subordinate, used merely to support it and unable, usually, to exist by themselves. In the epic theater all the arts are considered of equal importance and are used as independent elements; their relative importance changes as the production demands. To use Eisler’s simile, a musical-dramatic study-play is like a piece of counterpoint, in which separate melodies make individual tunes, but harmonize and balance one another so that they form a larger, better composition. “What dominates is the purpose of the whole,” Eisler says, “and the means must always be adapted to the purpose.” Even “pure” music must be useful. Of all the arts, music is the most subject to the art-for-art’s-sake dogma; but Eisler explodes this very simply. Music is meant to be heard by someone; if the listener feels it is of no value to him, he will soon stop listening. The question today is music for whose ears? Eisler turned from the concert-hall public–which has known him for years as a leader of modern music, annually represented at the Baden-Baden festivals–to the mass-public because he felt that only the working class could give music the new vitality and purpose it needed. “The function of proletarian music is to help the worker in his struggle by answering his musical needs. And just as the proletariat includes the whole range of human nature, from the simplest soul to the greatest minds of the modern world, proletarian music must cover the whole range of music.”

In the past the emotional power of music, like that of the theater, has been used mostly to induce the “state of trance”; but now music employs the emotional base only and always for practical purposes. The closed eyes of “romantic” music-lovers are as much a “wrong attitude” for Eisler as the tenseness of the “fascinated” theatergoer is for Brecht. They do not only want “absorbed” listeners, but alert listeners with both their eyes and ears wide open. But just as it is part of a lesson to suggest its interpretation, it is the part of music in the lesson to make this power of suggestion more powerful–in Eisler’s phrase, “to enforce an attitude.” His favorite example is the last scene of Mother, where he has written music that is “relaxed, not tense; light-hearted, not heavy-hearted”; instead of the militant or exalted music that might have been expected, “friendly, confident, free music”–to suggest the ideal interpretation of the words: “The final goal!” In sum, the proletarian composer, like the dramatist, must be able to control not only the emotional response of the listener, but also the use to which that response is put; the action to which it should lead. Music with a specific purpose cannot be given over to any one style or manner; it must be flexible to be useful. Sometimes it “interprets” the lesson, as in The Standard, where music suggesting the labored breathing of Chinese coolies at work makes their story more vivid; sometimes it emphasizes a statement by punctuation, rhythm; sometimes it is a dramatic protagonist, or a symbol, as in the scene of Mother, in which it represents the Party’s call for help. Sometimes it conveys its comment not by following the tenor of the narrative but by opposing a contrast: in Kuhle Wampe, for instance, a conventional composer would have written doleful music to accompany the scenes showing the wrecked homes of unemployed workers: but Eisler wrote “Solidarity.” The one thing educational art must always be is a call to action.

The New Masses was the continuation of Workers Monthly which began publishing in 1924 as a merger of the ‘Liberator’, the Trade Union Educational League magazine ‘Labor Herald’, and Friends of Soviet Russia’s monthly ‘Soviet Russia Pictorial’ as an explicitly Communist Party publication, but drawing in a wide range of contributors and sympathizers. In 1927 Workers Monthly ceased and The New Masses began. A major left cultural magazine of the late 1920s and early 1940s, the early editors of The New Masses included Hugo Gellert, John F. Sloan, Max Eastman, Mike Gold, and Joseph Freeman. Writers included William Carlos Williams, Theodore Dreiser, John Dos Passos, Upton Sinclair, Richard Wright, Ralph Ellison, Dorothy Parker, Dorothy Day, John Breecher, Langston Hughes, Eugene O’Neill, Rex Stout and Ernest Hemingway. Artists included Hugo Gellert, Stuart Davis, Boardman Robinson, Wanda Gag, William Gropper and Otto Soglow. Over time, the New Masses became narrower politically and the articles more commentary than comment. However, particularly in it first years, New Masses was the epitome of the era’s finest revolutionary cultural and artistic traditions.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/new-masses/1935/v18n01-dec-31-1935-NM.pdf