Report of the political situation in Yugoslavia and the work of its 3000-person Communist Party in the years between the Fifth and Sixth Comintern Congresses.

‘Report of Yugo-Slavia’ from The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

IN 1925 the ruling Serbian bourgeoisie succeeded in overcoming the acute government crisis and consolidated its position. This was done with the help of the Croatian and Slovenian bourgeoisie by forcing the republican peasant party of Croatia to capitulate and by igniting the other movements of oppressed nationalities against each other. Since then Yugo-Slavia has been in the grip of a general economic crisis, which has been reflected in the growing impoverishment of the peasantry with famine in several districts, systematic preparations for the establishment of a military Fascist dictatorship, and an ever-growing danger of war.

The relative stabilisation of currency and the good world harvest in 1925 brought about a serious agricultural crisis (a fall in prices of farm products, which averaged 38-40 per cent., whilst prices of manufactured goods decreased only 5 per cent.). As a result, the indebtedness of the peasants has risen to about 4 billion dinars.

In 1927 Yugo-Slavia suffered from a disastrous drought, which reduced the harvest by about 35 per cent.; in some districts 70 per cent. of the harvest was destroyed. This reduction in the crops, as compared with 1925, rendered the supply insufficient even for home consumption. But as a failure to export cereals would depreciate the currency, it was decided to export even though it operated to the detriment of the peasantry of those districts which buy grain even in normal years, thus bringing hunger and many cases of death from starvation to many districts (Montenegro, Dalmatia, and, especially, Herzegovina) . In spite of this the 1927 grain exports were still 70 per cent. short. Although imports have also decreased by 11 per cent., Yugo-Slavia has now an unfavourable balance of trade after three years of favourable balance.

Simultaneously, there is also a slump in industry with the exception of those industries which cater for the army. The crisis in the handicraft industry is still greater even than that in large-scale industry, having regard to the fact that the former depends mostly on the buying capacity of the peasantry. At the same time the State Budget is now more than 12 billion dinars, or 990 million Swiss francs, which is three times as high as the Budget of 1920-21, the period of inflation.

Impoverished Yugo-Slavia is now exploited more than ever by foreign capital. From America it received a loan of 62,250,000 dollars (receiving 86 dollars out of each 100, by which the nominal rate of interest of 7 per cent. was raised to 8.6 per cent.), and 25 million francs from Switzerland for the construction of railways for military purposes. Foreign loans also enabled it to cover the deficit in the budget and to make possible the stabilisation of its currency.

The Serbian bourgeoisie, headed by the royal Camarilla and the military, chiefs, are seeking a way out of the government and economic crisis by means of the establishment of a military-fascist dictatorship. The rights of Parliament are constantly being restricted, and the liquidation of Parliament advocated among the masses. Generals and leading officers are given high positions in the administration. By increased national oppression the existing régime hopes to overcome the resistance of the oppressed nationalities, and to force the bourgeoisie and the leaders of the peasant parties of these nationalities to support its policy.

The Yugo-Slavian conflict with Albania last year and the two open clashes with Bulgaria, arising out of the Macedonian incident, and also the constantly strained relations with Italy, show the acuteness of the war danger in Yugo-Slavia. To counteract the ambitions of Italian imperialism in the Balkans and its policy of surrounding Yugo-Slavia by countries under the influence of Anglo-Italian imperialism (Albania, Greece, Bulgaria, Rumania, Hungary) the Franco-Yugo-Slavian Pact has been concluded, which makes this danger even more acute. Through its policy of national oppression, particularly in Macedonia, the existing régime still further increases the war danger owing to the fact that all the border States of Yugo-Slavia have designs on Yugo-Slavian territory. Thus, in the event of war the State of Yugo-Slavia would probably be divided up.

The policy pursued by the ruling class has led to a re-alignment of forces in all the bourgeois and peasant parties. The royal Camarilla wants to establish one Serbian bourgeois party under its direct leadership by means of coalition between the two existing bourgeois parties—the Radicals and the Democrats. With this object in view the petty bourgeois Pashitsh majority has been driven out of the Radical Party, which has now become the obedient servant of the Camarilla. Similarly, the vacillating petty bourgeois Davidovitch wing of the Democratic Party, which was opposed to the Camarilla and to the Marinovitch banking interests, which, together with the Radicals, form the present government, has also suffered the same fate.

The bloc of the Serbian bourgeoisie embodied in the Vukicevic Marinkovic coalition succeeded in taking further steps towards the organisation of a bloc of the Serbian, Croatian and Slovenian bourgeoisie under the hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie and the leadership of the Camarilla. The Slovenian Clerical Party (Koroshetz), which derives its strength from the struggle for Slovenian autonomy, entered the bloc with a view to safeguarding the economic interests of the native bourgeoisie. The Musselmen of Bosnia (Spako) followed the same course on behalf of the Bosnian “Beks.”

To complete the dominant bourgeois bloc, the present régime seeks to organise a Croatian bourgeois Camarilla Party of the big bourgeoisie of the various Croatian parties, so as to create thereby a broad basis for itself.

This policy is opposed not only by the Croatian petty bourgeoisie but also by the Serbian peasantry. It has led to an ever-growing discontent among the peasants of these provinces, which has found expression in the organisation of the “Precanski-front,” i.e., “a front built from without” (outside of Serbia), and which organises the struggle of the peasantry of these provinces against the hegemony of the Serbian bourgeoisie. This “front” of the peasant Democratic coalition consists of two parties—Raditch’s Croatian Peasant Party and the Serbian Party of these provinces and the Independent Democrats under Privicevic’s leadership. The struggle of these two parties against the present regime and their desire to be allied with the working class has led to an attempt by the Zagreb capitalists to minimise this struggle by corrupting their leaders and directing them along purely Parliamentary lines.

The discontent of the Serbian peasants, especially those of Serbia, is taken advantage of by the Peasant League. Radical tendencies within the Peasant League are so strong that its leaders were forced to agree to the slogans of an alliance with the working class, distribution of the land, and unification of Yugo-Slavia with the Soviet Union—while, in reality, they pursued an outspoken opportunist policy, supporting the imperialist policy of the Government, and showing their readiness to enter into a coalition government.

The Socialist Party of Yugo-Slavia enjoys the full support of the Government, but, in spite of this, it received only 23,500 votes in the last Parliamentary elections. It pursues a very reactionary policy, favouring the splitting of the trade union movement, the suppression of the peasant movements, and supporting Serbian imperialism and its preparation for war, and participating in the campaign against the Soviet Union.

The Trade Unions.

There are about 1,200,000 wage workers in Yugo-Slavia, of whom only a small section is organised in six different trade union organisations. There are the Independent trade unions with 22,000 members, the Autonomous unions with 10,000 members, the Amsterdam unions with 23,000 members, the Croatian Workers’ Union with 2,000 members, and the Christian Socialist Unions of Slovenia with about 3,000 members.

The Red Trade Unions, which had in 1920 about 250,000 members, have since then been twice entirely dissolved, and even now the Independent trade unions cannot exist legally in some provinces. In recent years, however, they have re-appeared despite the terror. The reason for their slow development, although there is a favourable situation for the organisation of a wide revolutionary trade union movement, is primarily of a subjective nature, and is due, mainly, to the differences existing among the leading circles of the followers of the R.I.L.U., their sectarian and craft tendencies, and the inadequate and frequently wrong application of the united front tactic.

The Autonomous Trade Unions consist of the United Printing Workers’ Unions of Yugo-Slavia (5,000 members), to which are affiliated the followers of the R.I.L.U. and those of the Amsterdam International (both of which have about the same strength), and the four unions of bank and civil-servant employees of Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia and Voyvodina (a total of about 5,000 members), the R.I.L.U. being the strongest in the Serbian organisation. The autonomous trade unions work jointly with the independent unions for trade union unity, which was only frustrated as a result of the sabotage of the Amsterdam Unions.

The Amsterdam unions are decidedly opposed to any attempt at establishing a united front, and play the role of open blacklegs by throttling the strikes of the revolutionary workers.

Last year symptoms of a move to the Left and of greater activity of the working class made their appearance. This found expression, first of all, in a series of stubborn economic struggles, some of which lasted from two to three months. The movement of the unemployed has lately embraced broad sections, organised in unemployed committees. Mass meetings have been held notwithstanding government prohibition, resulting in mass demonstrations and clashes with the police.

The united front activities of the tenants’ movement, railway workers, State employees and factory workers, the organisation of a joint committee of action, etc., are symptoms of the same process.

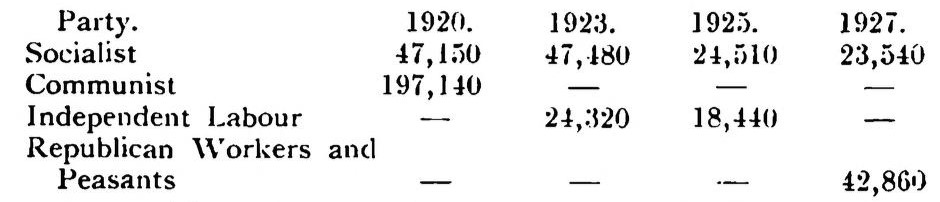

Lately we have for the first time witnessed labour protest demonstrations in the factories against the torture of Communists in prison. This leftward tendency is also reflected in the results of the elections of workers’ delegates in which, for the first time since the suppression in 1921 of the legal Communist Party and the Red trade unions, the tickets of the independent trace unions were almost everywhere successful. The municipal, district and parliamentary elections show—similar results. The four genera! elections which have taken place in Yugo-Slavia have given the following results:

In addition, there are important towns and districts where the Republican Workers’ and Peasants’ League received about as many votes or even more than the legal Communist Party in 1920.

The evidence of this move to the Left and the greater activity of the working class can also be seen from the following events:

In 1927 4,842 comrades were arrested in Yugo-Slavia, an many of them were sentenced to terms of imprisonment; a number of the comrades declared hunger-strikes. In the same year 50 national revolutionaries were killed, among them being several Macedonian comrades and one comrade each in Serbia, Dalmatia, and Bosnia.

With regard to the Press, a number of papers advocate the platform of revolutionary class struggle, an alliance of the working class and the peasantry; self-determination of the oppressed nationalities, sponsored by the revolutionary workers of Yugo-Slavia, through their Republican Workers’ and Peasants’ League, which conducted several political and economic campaigns. The revolutionary papers are: “Borba” in Zagreb (Croatia), with a circulation of 5,000, which will henceforward appear twice weekly; “Retch Radnika i Selyaka” in Liublina, a Slovenian weekly, with a circulation of 3,000 copies; “Radni Narod” in Podgovitch (Serbia), with 1,500 copies, a fortnightly; and “Nivi Pokret,” in Belgrade (Serbia), a fortnightly, with 2,200 copies.

The Republican Workers’ and Peasants’ League has succeeded in securing a firm footing in Dalmatia, Croatia, and Slovenia, especially among the peasants, which is seen from the numerous peasant conferences and the relatively high percentage of peasant votes it received. In Dalmatia the Left wing of the Croatian Peasant Party adopted its political platform.

There is an inner struggle going on in the Communist Party of Yugo-Slavia on vital fundamental and tactical questions. There are differences in the estimation of the political situation, of the national and peasant problems, on the question of the tasks of the trade union movement, and the organisational questions of the Party.

The struggle among the party leaders has shown that the party has not yet been able to eliminate entirely the remnants of right deviations and unhealthy forms of fractional struggles. In order to put an end to fractionalism, which hampered the development of the C.P.Y.S. and its activity among the broad masses of workers and peasants, the E.C.C.I. sent an open letter in April of this year to the party membership, prior to the Party Congress. The letter points out the most important mistakes of the party and of both fractions, and how to bring about consolidation of organisation by promoting new leaders from among the rank and file workers, and by overcoming the fractional and sectarian spirit.

The party publishes two illegal organs: “Klasna Borba” (Class Struggle) and “Sop i Celcic” (Hammer and Sickle). Apart from this the party issued several illegal pamphlets, among which were Stalin’s work on Leninism, and various Lenin writings, etc. The party has over 3,000 members.

The Communist International Between the Fifth and the Sixth Congresses, 1924-28. Published by the Communist International, 1928.

PDF of full book: https://archive.org/download/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2/comintern_between_fifth_and_sixth_congress_ao2.pdf