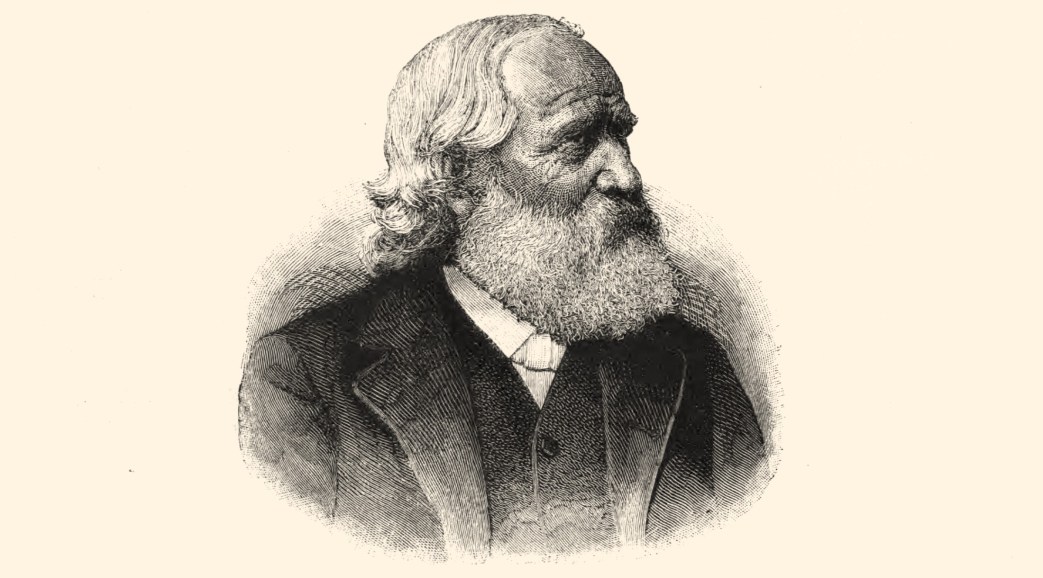

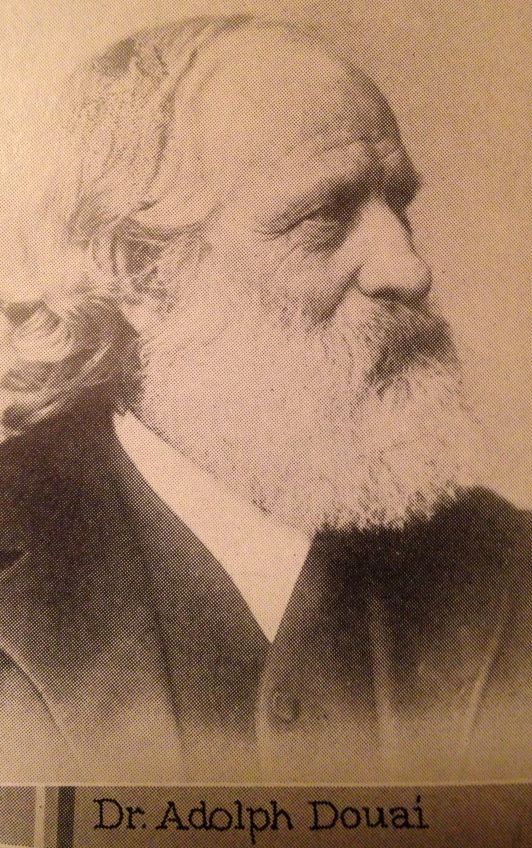

A report of the funeral and valuable autobiography of Adolph Douai; Red ’48er, pioneering U.S. Social Democrat, abolitionist, educator, writer, editor, and decades-long Socialist activist.

‘Dr. Adolph Douai: The Gifted and Tireless Agitator Dead’ from Workmen’s Advocate. Vol. 4 No. 4. January 28, 1888.

A Proletarian Who Lived for the Good of Others — His Autobiography — Teacher, Revolutionist, and Scientist —A Useful Life

Last Saturday morning the self-sacrificing teacher and agitator, Dr. Adolph Douai, consciously and calmly departed this life, at the age of 68 years and 11 months. He had been suffering from a throat trouble, but no fears were entertained by his family, and he refrained from telling them of his condition when he became convinced of the serious character of the ailment.

The funeral took place last Tuesday, from the Brooklyn Labor Lyceum, where thousands gathered to pay the last respects to the deceased. The Sections of the Socialist Labor Party of New York, Brooklyn, Williamsburg, Greenpoint, as well as a number of socialistic societies and trade unions, among them the Bricklayers’ International Union No. 11 and the Socialist Turn Verein, and the delegates to the German Trades; besides these there were representatives from Socialist Sections in Philadelphia and New Jersey, and from a number of trade unions in New York and neighboring cities.

The Progressive Musical Union rendered exquisite music suitable to the occasion, and the scholars of the Labor Lyceum school sang a mourning hymn. Alexander Jonas, editor of the Volkszeitung, made the first address, in which he reviewed the life of the deceased and feelingly acknowledged his excellent traits. After a song — “Dort unten ist Friede” — by the Lassalle Mannerchor, Dr. Felix Adler rendered a glowing tribute to the memory of Dr. Douai, in which he especially noted his high character and faithfulness to his convictions. Teacher William Scholl, of the Douai Institute, spoke on behalf of the teachers and scholars of the school, and closed by laying a palm branch upon the casket.

Herman Walther spoke in the name of the National Executive Committee of the Socialist Labor Party. He said:

“Adolph Douai has been described as a teacher and philosopher, and what have we, Social Democrats, to say? We known how to appreciate his many excellencies, but that which lifts him higher in our sight is his unbending characteristic of honor. To Social Democrats he shall be as a bright example. As to his ideals, I do not believe that the many were against him, but rather that the masses of the people, of the thinking proletariat, were on his side. He was a fighter for freedom. A son of the people, he passed through the hard school of life, and thus comprehended the suffering of the people. He was ever in advance of his time, ever progressive. He was a pioneer of the enlightened proletarians, and as such is honored by the working people of all countries, and will ever live in their memory. In him has the great prophecy of Lassalle been fulfilled: “Science and Labor have embraced.”

With these words the speaker deposited a wreath of white flowers and evergreen upon the bier. Comrade G. Metzler, of Philadelphia, also laid a wreath upon the coffin in the name of the Socialists of Philadelphia, and Jacob Willig offered a wreath of laurel entwined with a crimson sash, in the name of the United German Trades, with the inscription: “To the brave battler for Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity.”

Many other tributes were offered in flowers, poetry, and song, after which the funeral procession was formed and the mortal remains of one whose deeds shall live after him were carried to their resting place in Evergreen cemetery.

Dr. Douai’s Autobiography.

Following is a translation of Dr. Douai’s autobiography, slightly condensed:

Charles Daniel Adolph Douai was born at Altenburg, in the Duchy of Saxon-Altenburg, on the 22nd of February, 1819. He was the son of a school teacher, and a descendant of a French refugee family who had fled to Dresden and forgotten their French. His father was the first teacher of the “Semi-school” in Friedrichstadt-Dresden, until the pedagogic reformer, Dinter, was called thither, and who in his autobiography appreciatively referred to the elder Douai. Here his son received his education and training as a teacher of the people, so that teachership was inherited to the fourth generation in this family.

Adolph Douai received a good academic and university education, according to the conception of those days, for the Altenburg Gymnasium and the University of Leipzig which he attended were celebrated. But although he had graduated from both with honor, poverty was so closely interwoven with his fate that he begged of his father to permit him to learn the trade of compositor, which idea was opposed and vanquished by his stern parent.

From his eighth year he had to partially support himself, and from his thirteenth year he was entirely dependent upon his own exertions for a livelihood, so slight was his father’s salary and perquisites. He wrought out a livelihood as a newspaper carrier, as assistant to his father in the teaching of a number of peasant children, as copyist, as chorister, as assistant in the preparation of a schoolbook by his father, as crocheter of woolen shawls which father and son manufactured in leisure hours, as composer of special poems, as peddler of the schoolbook referred to, as messenger, as children’s caretaker, and as cook, when his mother was ill, as actor in child casts, theatrical supernumerary and re-writer of actors’ librettos, and finally also as composer of New Year’s and birthday poems for several wealthy relatives who paid for the work, and in many other ways. All this prevented a thorough attention to study, nor could he devote sufficient interest in the teaching. Every waking moment he was away from his studies was necessarily devoted to the struggle for existence, and he was permitted to enter examination for graduation from the academy a year earlier than was the rule, for it was considered that he would fatally overwork himself if he had to pass another year in the struggle for an education and at the same time for a living. At the age of 19 he was a physically undeveloped, half-nourished boy, and measured 4 feet, 8 inches in height, as shown by his passport. Admitted to the freedom of the University, where he received a few stipends, he exercised in the gymnasium, fenced, swam, and roamed the fields, as circumstances permitted, he grew and improved so rapidly that his father hardly recognized him after a few months’ absence from home.

At the University, poverty asserted its power, and the stipends were not sufficient to support the poor student. He was compelled to add to his income by writing, and he wrote some novels and two theological papers. Notwithstanding this he had to live in a room without fire in the winter and live on poor fare. This did not hinder him from joining, for a half-year, with the students in their rollicking life, and incurring beer debts, etc., for the sake of actual and new experience. For the same reason he traveled on foot all over Germany, as was customary with the journeymen workmen, having very little money in his pocket.

After he graduated from the University, he sought admission as student in philosophy and pedagogy at the University of Jena, in vain. It would require two years of support by private means to enter upon the usual course of a German scientist. There was but one course for him, and that was the acceptance of a good paying situation as private tutor in Russia. This could furnish him the means to continue his studies and at the same time marry, for he was betrothed to Baroness von Beust, and receive the consent of her relatives only on condition that he could, within two years, succeed in securing a respectable and paying position.

This was accomplished, but to related all the adventures and contests necessary to gain all this would take too long. Douai successfully passed imperial examinations at the University of Dorpat, which entitled him to admission in Russian government employ and to the title of Doctor and the rank of Professor, whereupon he claimed his bride. He soon became conscious that acceptance of an office under the Russian government would involve the sacrifice of his ideals and convictions, and so he accepted a position as private tutor at a high salary, which left him with enough time and means to continue his studies. Here his convictions and principles ripened; here he struggled against the uneducated public opinion, through to Social Democracy, in which his own experience, having comprehended the system of exploitation and seen the consequent human misery, considerably influenced him. Among other experiences, he lived through a three-years’ famine, a peasant revolution, the first persecution of Nihilists, and the forcible or bribed conversions of protestant peasants to the Greek church — all these occurred under his own eyes.

His personal circumstances were now highly pleasing. He never expected a more congenial life, or more appreciation. But, the certainty that Russia would not prove a field for one of his opinions, and an uncertain premonition of a coming revolutionary movement in Western Europe, drove him back to Germany after a five years’ residence in the Tsar’s domain.

Douai had become thoroughly convinced that the art and science of education had a great future — the task of ennobling humanity — and that this was possible and imperious. Possible, because humanity had lifted itself above the lower order of animal life; but imperious, because the ever-repeated destruction of civilization could only be prevented by a Social Democratic revolution in all social arrangements, combined with a reform in the means of education which should partly precede this revolution, and partly follow it as a support.

In his paternal city, Altenburg, Douai endeavored to enhance the value of his new primary and preparatory school by never refusing admittance to ever so spoiled a scholar, as he hoped by improving such to gain a reputation. And this succeeded. Although he bought and fitted up a building, and engaged the best assistants with borrowed money, he had paid all debts within a year and a half, and his institution prospered, so that scholars came from considerable distances, while the children of proletarians were ever welcomed.

Then came the Revolution of 1848, and as he had helped prepare for it by the organization of young citizens’ clubs, journeymen’s and laborers’ societies, he took an active part in the political development. Little Altenburg declared for the Republic and Social Democracy as early as Frederick Hecker (the name Social Democracy was spoken even then though but partially comprehended). After it had been vainly attempted to swerve him by bribes and promises of high office, he was threatened with arrest as early as July, as were two of his comrades. But the citizens erected barricades, and repelled a brigade of Saxon troops which the government had secretly quartered there, and with such energy that they were withdrawn.

A Reform Council (Landtag) was called, in which Douai and his comrades were in the majority, and the reformation thereof followed within a few months. But he was one of the few who were not deceived by the present non-success of the Revolution, for Altenburg was one of the most progressive portions of Germany, as was the neighboring kingdom of Saxony, where his propaganda also entered; but many a broad tract of Germany was still in darkness. It was his notion to spread, among the million of people who came within range of his agitatorial influence, as much light as possible upon political, religious, social, and scientific subjects, and at the same time to warn against all unnecessary bloodshed. The fruits of such activity could not be lost, and were not.

It was the part of the government to nullify his influence, but that was in vain for at least four years. On the pretense that Altenburg was a “strategical point,” a brigade of Saxon troops was quartered there. These were quickly republicanized. They were sent to Schleswig-Holstein, and with them the two republicanized local battalions. In their place came a brigade of Hanoverians. These were also soon republicanized. Then came a brigade of Prussians, among them two regiments of Polanders.

Before this Douai had actually been arrested, and only by quick presence of mind and firmness did he prevent bloodshed, for the citizens had already set him at liberty, throwing himself between the people and the bayonets of the soldiery, after which he presented himself a free man before court for trial.

In the trial on charges of high treason and rioting, he prevailed, but the jury seemed to think they must placate the government, and so he was sent to prison for one year on three counts. Through this and during this time his school was broken up, and influences were brought to bear upon him, evidently planned by the government, to emigrate. But he found a new means to earn a living, and only after these had been destroyed by the government did he determine to leave Germany. The sale of his property was forced, and his means were thus retrenched; but the gratitude of his fellow citizens was made manifest in the liberal furnishing of the needful means for his journey and establishing himself in a new country — Texas. There, at the new German colony of New Braunfels, he established a school. The population was mostly composed of Catholics, and as soon as the pupils had mastered the elementary branches, which hardly occupied three months, they were withdrawn from his school by influence of the priest.

Then he was attacked by that dread disease, cholera, after which he contracted a fever; and so his school again was broken up. He endeavored to earn a living for himself and family by giving private lessons in music, arranging concerts, tuning pianos, and taking the leadership in a male singing society, in vain. As a last resort he turned his attention to newspaper work in San Antonio. His program was Social Democratic, and it took well. When, however, the San Antonio Zeitung came out in both German and English espousing the cause of the Abolitionists, denouncing slavery, he was subject to multifarious persecutions, which ended in the destruction of his paper, and a total loss of his little property. Nor could he emigrate but for the help of friends, for all Abolitionists were driven out. But the Negroes did not forget him. In 1860 he received a newspaper which said in the salutatory:

“This paper, which is owned, edited, and whose types are set by Negroes, is printed upon the same press with which Dr. Adolph Douai first battled for the emancipation of the black men. He has the gratitude of the colored race who will ever remember his endeavors in behalf of freedom. “

Douai took part in the Frémont campaign, and at the same time strived for the establishment of Western Texas as a free state. But the war coming on, the plan failed after the Kansas Emigrant Aid Society had voted to spend a million dollars in the effort.

He then went to Boston, where he began life by giving private lessons. Besides, he became interested in the Institute for the Blind, supported by the six New England states, in South Boston, where he labored for several years imparting knowledge to the unfortunates. A German workingmen’s club which he organized helped in the establishment of a three-class school with which a Kindergarten was connected — the first in America. On the occasion of a memorial meeting in honor of Humboldt, Douai delivered a speech in which he said that one of the services to humanity of Humboldt was that he was not a believer in God. For this he was so bitterly attacked by Professor Louis Agassiz and his brother-in-law, Professor Felton, in the Boston press, that his means of support were withdrawn and he had to leave his beloved Boston.

In 1860 he became editor of the New York Demokrat, but soon accepted the position of Principal of the Hoboken Academy, which prospered exceedingly under his management. Here he worked 6 years, when he observed that his political, religious, and socialistic opinions (which, however, were not paraded in the academy) had made him powerful enemies. He removed to New York in 1866, and established a school of his own, which soon prospered. The Tweed-Sweeney swindle in the widening of upper Broadway cost him his property by the nullification of a long lease through special lawmaking. His school still exists under the direction of his sister, but he had to find a new field for existence with his family of 10 children (1871). He was elected principal of the Green Street School, Newark, NJ, and remained there until 1876. The number of scholars rose from 198 to 450. He stipulated that his plan of teaching should not be interfered with and held himself ready to resign when this stipulation was broken; and this occurred in the election of a Board of Directors who were politically opposed to him. He then accepted an invitation to establish an academy at Irvington, NJ, for which purpose stock was subscribed. But the loss of the only building in the place suitable for the undertaking prevented the project from being carried out.

He had already begun writing for the Volkszeitung, established in January 1878, and he now closed his career as a teacher, and devoted himself to editorial work on the Volkszeitung, though he still occasionally taught at his sister’s school. As a teacher he published 10 textbooks, 6 English and 4 German, and in all of them gave the benefit of his half-century of teacher’s experience, besides contributing to the best English and German pedagogic newspapers and magazines. As all this was more for the school of the future, it may easily be imagined that his pedagogic writings cost him more than it brought in. These works may still be appreciated; they have been the result of long experience in the school room.

Teaching was a passion with him, and he only turned his attention to writing when there was no alternative. Six times he lost all his property at schoolkeeping, without fault of his own, because he would not hide his convictions nor sacrifice his pedagogic principles. He is known more as a writer than as a teacher, and yet he taught over 5,000 children, and among them some have become celebrated and excellent people. He has been charged with unsteadiness owing to his many changes — the foregoing will teach whether these charges are well founded. One may discover in the perusal of this story that for a born proletarian who will not deny his principles, it is mad almost impossible to accomplish material success in “this best of all worlds,” even if he were, if possible, more industrious, economical, persevering, and free from gross vices than Douai; at least not as a teacher.

His journalistic and literary productions would fill many volumes. Many of them remain unpublished.

The Workmen’s Advocate (not to be confused with Chicago’s Workingman’s Advocate) began in 1883 as the irregular voice of workers then on strike at the New Haven Daily Palladium in Connecticut. In October, 1885 the Workmen’s Advocate transformed into as a regular weekly paper covering the local labor movement, including the Knights of Labor and the Greenback Labor Party and was affiliated with the Workingmen’s Party. In 1886, as the Workingmen’s Party changed their name to the Socialistic Labor Party, as a consciously Marxist party making this paper among the first English-language papers of an avowedly Marxist group in the US. The paper covered European socialism and the tours of Wilhlelm Liebknecht, Edward Aveling, and Eleanor Marx. In 1889 the DeLeonist’s took control of the SLP and Lucien Sanial became editor. In March 1891, the SLP replaced the Workmen’s Advocate with The People based in New York.

Access to PDF of full issue: https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn90065027/1888-01-28/ed-1/seq-1/