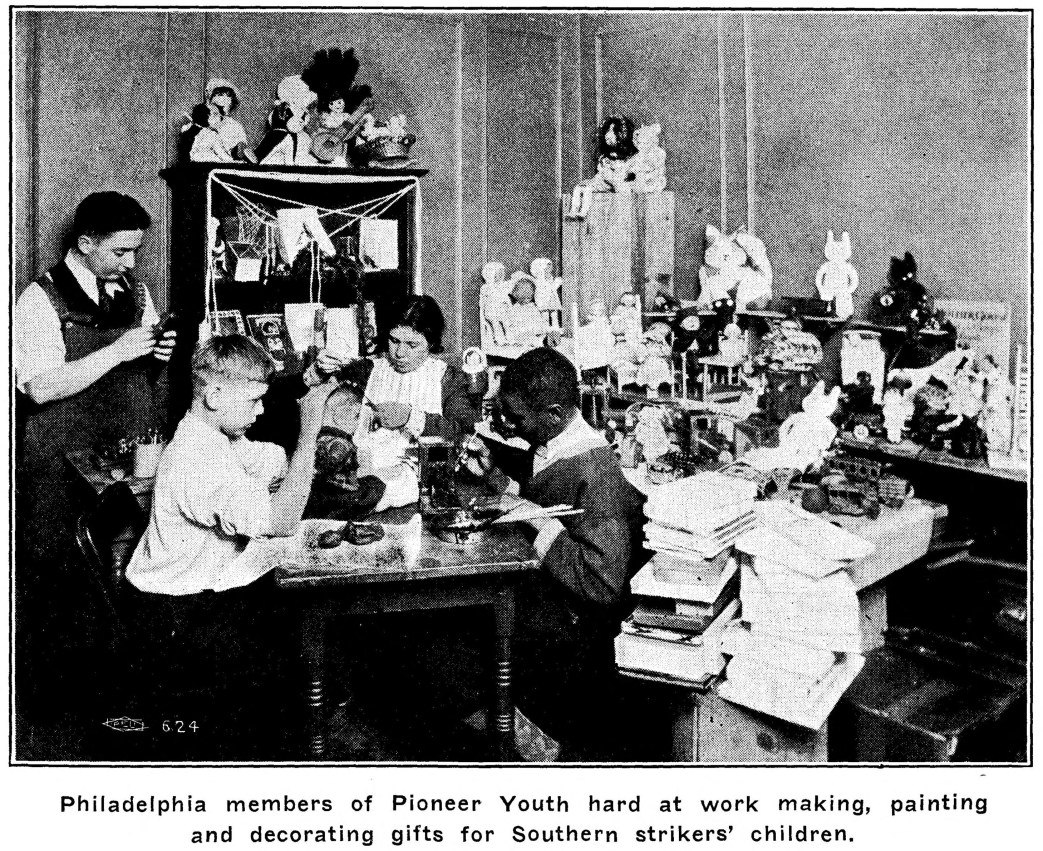

Working class children of the East Coast makes toys for the kids of striking mill workers in Marion, North Carolina during the hard-fought strike which had seen six strikers murdered that fall.

‘Santa Visits Marion’ by W. Walter Ludwig from Labor Age. Vol. 19 No. 1. January, 1930.

It is Christmas Sunday evening in Marion. The holiday spirit is unmistakably in the air. Before the county courthouse stands a stately evergreen, brilliantly lighted “by the power company” the waiter informs me with a touch of civic pride.

At the churches “white gift” services are being conducted today. Hundreds of gifts brought by the worshippers are heaped about the altars and tomorrow will be distributed under the supervision of the Chamber of Commerce to the county’s poor. Tonight at one of the churches a white robed choir affirmed in cantata the coming of the “Prince of Peace.” I thought of six snow covered graves across the valley. To Marion?

With Hugh Moore, director of relief for the Friends Service Committee, whose car had broken down, I tramped through the snow to the mill village of East Marion. I found an elemental joy in wading into the storm, feeling the snow drive into my face. It covered things equally, comfortable Marion behind us and the mill workers’ homes looming ahead, gray against glistening white. Hadn’t this Jesus about whom they were singing in the churches said something about the rain falling alike on the just and the unjust? If only North Carolina justice were equally impartial! Eight deputies accused of murder are free, home with their families tonight. Merry Christmas! But what of Cora Hall and old Airs Jonas? And the strikers sentenced to six months on the roads? Merry?…The snow beats into my face. It too is cold. Like Justice. But fair…

At the commissary Roy Price, president of the local union, joins us and we stamp off in final search of a place where the Christmas party of the strikers’ children can be held tomorrow afternoon. The school and one of the churches have been approached and refused. We appeal to the clerk of the Baptist church which had summarily dismissed ten members on strike. “It’s either your building or a Christmas party in the snow.” He will let us know tomorrow morning at the company store.

Monday morning. Stacks of colorful toys have invested with a holiday air the little cabin used as a clothing dispensary. The toys, more than 2,500 of all sizes and varieties, have been sent from the shops and clubs of Pioneer Youth of America, an organization of workers’ children in Baltimore, New York, and Philadelphia. For a month these children have been repairing, painting, and making the toys. Their appeal for playthings brought donations from clubs of business and industrial girls of the Y.W.C.A., from the Saturday School of the First Presbyterian Church, New York City, from a Baptist church in Cleveland, from two Socialist Sunday Schools in Brooklyn, and from other interested individuals and organizations.

Jimmy, a nine year old, sidled up to me as I was unpacking a huge case from Philadelphia. “That’s what I want,” he said, pointing to a toy dump truck. The truck I afterwards learned had been given by George, a Pioneer Youth club member whose father, a member of the United Textile Workers, had himself been on strike last summer. “I’ve been a-wanting one of them a long time,” Jimmy hinted. I watched him manipulate the truck and marvelled that he knew exactly how it worked. That night, hurrying to my train, I saw the identical truck in a hardware store window in town. Plainly Jimmy’s nose with that of a half dozen other “mill kids” had at some time pressed against the window, admiring toys which his parents could never buy.

They laughed when I announced that Jimmy had spoken for the truck. “Wild kid,” somebody said. ”Maybe it will keep him at home.” Jimmy, it seems, runs away from home. His last escapade was to Ashville where he was found and returned by the Salvation Army and given four days in jail for delinquency by Marion justice.

At the party that afternoon Roy Price told me as he looked into the faces of his people, 500 of whom crowded into the church building which had been given without reservation, “I’m proud of this. Nobody knows how proud I am. Some of the school teachers told our children that Santa Claus won’t come to see you this year.” Santa was there all right in the person of 50 year old Dell Lewis, one of those sentenced to six months on the roads for rioting. And there was a Christmas tree, not so fine as the one by the courthouse but cut and decorated by the strikers themselves.

After the Christmas carols there were talks by Hugh Moore and William Ross, and a brief presentation of the toys in behalf of the children of Pioneer Youth and their friends. Winifred Wildman and Betty Fowler, social worker and nurse for the Friends committee, supervised the distribution of the toys and treats of nuts, candy, and fruit. Every family received its quota and those who couldn’t come had theirs delivered the next day.

Who said “there ain’t no Santa Claus?” To Marion strikers and their families he’s a lot more real and more friendly than a statuesque and hoodwinked lady called justice.

Labor Age was a left-labor monthly magazine with origins in Socialist Review, journal of the Intercollegiate Socialist Society. Published by the Labor Publication Society from 1921-1933 aligned with the League for Industrial Democracy of left-wing trade unionists across industries. During 1929-33 the magazine was affiliated with the Conference for Progressive Labor Action (CPLA) led by A. J. Muste. James Maurer, Harry W. Laidler, and Louis Budenz were also writers. The orientation of the magazine was industrial unionism, planning, nationalization, and was illustrated with photos and cartoons. With its stress on worker education, social unionism and rank and file activism, it is one of the essential journals of the radical US labor socialist movement of its time.

PDF of full issue: https://www.marxists.org/history/usa/pubs/laborage/v19n01-Jan-1930-Labor-Age.pdf